auschwitz

While escape seemed impossible, there were a number of successful escapes from the horrific Nazi death camp known as Auschwitz. Unfortunately, there were also many failed attempts. These escapes and attempted escapes happened, because where people are held in captivity, they will rebel and try to find a way out, and when death is inevitable, escape become less risky. Hitler wanted all the Jews dead, and while he might have tried to hide his true intentions from the world, he certainly didn’t hide it from the Jews themselves.

While escape seemed impossible, there were a number of successful escapes from the horrific Nazi death camp known as Auschwitz. Unfortunately, there were also many failed attempts. These escapes and attempted escapes happened, because where people are held in captivity, they will rebel and try to find a way out, and when death is inevitable, escape become less risky. Hitler wanted all the Jews dead, and while he might have tried to hide his true intentions from the world, he certainly didn’t hide it from the Jews themselves.

Most prisoner escapes took place from worksites outside the camp. The attitude of local civilians was of immense importance in the success of these efforts. Some of the escapees tried to get the word out that the camps were not just work camps, but were also death camps, and that the people should fight with everything they had to avoid going. Of course, all too often, any reports were suppressed as much as possible by the Germans, and for the most part, the reports did little to no good.

On escape that particularly touched me was the escape of two Slovakian Jews, Rudolf Vrba (born Walter Rosenberg) and Alfred Wetzler, escaped in April 1944. They knew the consequences of the were caught, and the men in their barracks knew the consequences of helping them, or even being in the same barracks with them. Nevertheless, all of them felt that the risk was worth it to try to get the truth to the outside world.

Trust was vital, in an escape. Vrba and Wetzler came from the same town, so they knew each other well, and could trust each other. The men had been working on this escape idea for a while, coming up with plans and then rejecting them, because they couldn’t work. Finally, Wetzler came to Vrba with a plan that just might work. They would hide in a pile of wooden planks and after the three-day search for the escapees was finished,  they would escape and head South. The plan was good, but there were still a number of obstacles to maneuver. The first group to attempt the escape were later caught in a village south of the camp, but the wooden plank plan had worked, and the captured prisoners did not reveal their strategy.

they would escape and head South. The plan was good, but there were still a number of obstacles to maneuver. The first group to attempt the escape were later caught in a village south of the camp, but the wooden plank plan had worked, and the captured prisoners did not reveal their strategy.

So, Vrba and Wetzler waited two weeks, and put their plan in motion. The had a friend help them by pulling the planks over then, and covering the area with something to hid e the scent of the men from the dogs. The men expected the alarm to sound at the 5:30pm roll call, but no alarm sounded. The men began to think that someone had told of their location, and that the guards would be coming any minute, but the alarm went of shortly after 6:00pm and the sound of boots and dogs was everywhere. It was all they could do not to scream in terror. Nevertheless, they held their peace and stayed put.

The men laid motionless for three days with no food or water. They were stiff and cold, but finally, they heard the guards call off the search, so that night they decided to come out of the wood pile and make their escape. However, the planks wouldn’t budge. They pushed and pushed…almost to the point of panic. They determined that they would not die there, they gave it one last effort, and the planks gave way. They came out into the night, made their way to the nearest fence and crawled under the barbed wire. I’m quite sure they never wanted to see a fence again.

The ran for the woods, traveling at night, and hiding by day. They were seen by a few people, but thankfully everyone who saw them was sympathetic to their cause and helped them on their way. Finally, they crossed the

border, and they were free at last. They went to Zylina, where they met secretly with officials from the Slovakia Jewish Council and gave them a secret report on Auschwitz. An in-depth report was drawn up in Slovak and German. The plan was to get the report to the world before another train load of Jews could come to Auschwitz, and the men had done their part. They had done all they could. Unfortunately, the report did not get to those who needed to hear it, and the killing would go on until January 27, 1945, when Auschwitz was finally liberated.

border, and they were free at last. They went to Zylina, where they met secretly with officials from the Slovakia Jewish Council and gave them a secret report on Auschwitz. An in-depth report was drawn up in Slovak and German. The plan was to get the report to the world before another train load of Jews could come to Auschwitz, and the men had done their part. They had done all they could. Unfortunately, the report did not get to those who needed to hear it, and the killing would go on until January 27, 1945, when Auschwitz was finally liberated.

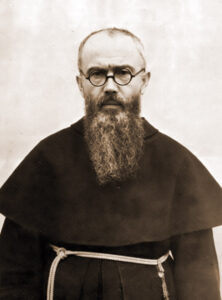

Heroes come from all walks of life, and you really never know who will become a hero and who won’t. In fact, I don’t think a hero even knows that the heroic in inside him, until the heroic is needed. Often the heroic comes from being faced with a situation that would require your life to save that of another. Such was the case for Maximilian Kolbe in 1941.

Heroes come from all walks of life, and you really never know who will become a hero and who won’t. In fact, I don’t think a hero even knows that the heroic in inside him, until the heroic is needed. Often the heroic comes from being faced with a situation that would require your life to save that of another. Such was the case for Maximilian Kolbe in 1941.

The Catholics didn’t really agree with the Jewish beliefs, and the Jews felt the same way about the Catholics beliefs, so when Hitler began rounding up the Jews, many Catholics and other religions, were quick to turn them over…it might have been to save their own lives, but they were handing them over to be killed, nevertheless…and they knew it. The non-Jews could pretend that everything was fine and the Jewish people who were taken, would be returned when things settled down, and maybe at first they truly thought that, but as time went by the truth was coming out. They now had a choice to make…a moral choice.

Kolbe was a Catholic priest during World War II. He saw what was going on with the Jewish people, when Hitler started rounding them up. Kolbe could read between the lines, as many people could in those horrific days, and he decided to help Jewish people escape the Nazis. Being a Catholic priest, he likely had more room that other  people might have had. He started harboring Jewish people and hiding them from the Nazis, keeping them safe from the public and any harm that might be afflicted upon them. As with many people who harbored Jews, Kolbe was soon caught, and was sent to Auschwitz for sheltering Jewish people.

people might have had. He started harboring Jewish people and hiding them from the Nazis, keeping them safe from the public and any harm that might be afflicted upon them. As with many people who harbored Jews, Kolbe was soon caught, and was sent to Auschwitz for sheltering Jewish people.

Auschwitz was one of the worst of Hitler’s torture chamber death camps, and it certainly proved to be just that for Kolbe. During his time at the horrid concentration camp, a prisoner escaped from the camp and as punishment, ten innocent prisoners had to starve to death in a hollow, concrete tube. One of the elected people started to cry and exclaimed that they had a wife and kids, so Kolbe spoke up and took his place so the man could be with this family. The prisoners were kept in the tube for the next two weeks. Most of them were already in a weakened and starved state, and so the prisoners inside the tube slowly began to die. Of the ten prisoners, Kolbe and  three other men managed to survive the torturous tube. One would think that if they survived the tube, they would be considered strong enough to bring out and put back to work, but the remaining prisoners were brought out of the tube and killed by being injected with Carbolic Acid. When it was his turn to receive the injection, Kolbe didn’t fight like the rest of the men, but instead, he gave his arm to the prison guard and never once made a fuss over it. One might think that Kolbe was just done with the whole mess, and maybe that was true, but it would have made no difference for him to fight. The guards had decided, and his fighting the injection would make no difference. Maximilian Kolbe died on August 14, 1941. He was 47 years old.

three other men managed to survive the torturous tube. One would think that if they survived the tube, they would be considered strong enough to bring out and put back to work, but the remaining prisoners were brought out of the tube and killed by being injected with Carbolic Acid. When it was his turn to receive the injection, Kolbe didn’t fight like the rest of the men, but instead, he gave his arm to the prison guard and never once made a fuss over it. One might think that Kolbe was just done with the whole mess, and maybe that was true, but it would have made no difference for him to fight. The guards had decided, and his fighting the injection would make no difference. Maximilian Kolbe died on August 14, 1941. He was 47 years old.

Approximately 3,000 twins were pulled from the masses on the ramp at Auschwitz, most of them were children; only around 160 of them survived. As the trains rolled into Auschwitz, the guards were trained to watch closely. They were looking for strong workers, the elderly, and the weak, and they were looking for twins…especially identical twins. The parents of these twins were thankful that they had twins…at first. They seemed to know that their twins would not be sent to the gas chambers, but they did not know that they would be taken away from them forever, and that they would be sentenced to a life of torture in the hands of a madman. The Nazis didn’t care about the feelings of the parents whose twins were yanked from their arms. They knew that Dr Josef Mengele wanted these twins for his medical experiments. Mengele wanted to find a way to cause more twin births to increase the Nazi world population. He also wanted to find a way to manipulate the traits twins had so that if they were blonde haired, a trait that supposedly meant that they were half Aryan. That said, he wanted to bring any problematic areas into line, such as the lack of blue eyes. He would inject chemicals into their eyes to try to turn their eyes blue. And that was just part of his insanely sadistic experimentation.

Approximately 3,000 twins were pulled from the masses on the ramp at Auschwitz, most of them were children; only around 160 of them survived. As the trains rolled into Auschwitz, the guards were trained to watch closely. They were looking for strong workers, the elderly, and the weak, and they were looking for twins…especially identical twins. The parents of these twins were thankful that they had twins…at first. They seemed to know that their twins would not be sent to the gas chambers, but they did not know that they would be taken away from them forever, and that they would be sentenced to a life of torture in the hands of a madman. The Nazis didn’t care about the feelings of the parents whose twins were yanked from their arms. They knew that Dr Josef Mengele wanted these twins for his medical experiments. Mengele wanted to find a way to cause more twin births to increase the Nazi world population. He also wanted to find a way to manipulate the traits twins had so that if they were blonde haired, a trait that supposedly meant that they were half Aryan. That said, he wanted to bring any problematic areas into line, such as the lack of blue eyes. He would inject chemicals into their eyes to try to turn their eyes blue. And that was just part of his insanely sadistic experimentation.

Ten-year-old Eva (Mozes) Kor and her twin sister, Miriam (Mozes) Zeiger, were one of these surviving sets of twins. The twins were born on January 31, 1934 into a Jewish farming family in the village of Portz in northern Transylvania, which was a part of Romania at the time, but later became a part of Hungary, which came under German military occupation in late World War II. Their family was deported to Auschwitz in late 1944, a fact which probably was to their advantage, because they were at Auschwitz for a shorted time that some survivors. The twins father, Alexander; their mother, Jaffa; and sisters, Edit and Aliz; all died at Auschwitz.

Eva and Miriam spent nine months in the clutches of Dr Mengele, during which time he would inject them with mystery cocktails of germs, viruses, and chemicals…just to see how they would react. Following one such injection, Miriam’s kidneys stopped growing. They remained the size of a child’s for the rest of her life. Eva recalls that after one injection, she became very ill, with a high fever. During her illness, she kept telling herself that she must survive, or else Miriam would become “surplus to requirements,” meaning that she would be given a lethal injection of something so that dual autopsies could be performed on them. Mengele wanted to see any differences the twins might have. The girls were determined that they would survive for each other.

Dr Mengele who has killed about 1,500 pairs of twins in two years, was known to perform horrible surgeries on twins, without anesthesia. One day the girls saw a set of twins brought into the barracks after surgery. The twins had been connected at their backs. Their organs had been interconnected. They were in horrible pain, and they died a short time later. While the “Mengele Twins” were given “special privileges” in some ways, better clothes and food, they were not spared the horrors of death. They saw it all around them, and they had no one to comfort them after they witnessed these horrors.

Then it happened…on January 27, 1945, while Eva and Miriam are lying in their bunks, the girls heard shouts of

“We’re free! We’re free!” They ran to the door of the barracks, but couldn’t see anything for a few minutes because of the snow. Then they saw the Soviet soldiers in white camouflage. It was a wonderful day for them. The girls immigrated to Israel and lived in a Kibbutz that had been set up for children orphaned by the Holocaust. The grew up and both married, but only Eva had children. Miriam passed away on June 6, 1993. Eva went on to forgive the Nazis for the atrocities against the Jews. She not only forgave them, but she took young people on annual tours of the Auschwitz complex, because she didn’t want people to forget what happened there. She actually passed away while on one of those tours on July 4, 2019. These were amazing women. Would that we could all forgive in such a manner.

“We’re free! We’re free!” They ran to the door of the barracks, but couldn’t see anything for a few minutes because of the snow. Then they saw the Soviet soldiers in white camouflage. It was a wonderful day for them. The girls immigrated to Israel and lived in a Kibbutz that had been set up for children orphaned by the Holocaust. The grew up and both married, but only Eva had children. Miriam passed away on June 6, 1993. Eva went on to forgive the Nazis for the atrocities against the Jews. She not only forgave them, but she took young people on annual tours of the Auschwitz complex, because she didn’t want people to forget what happened there. She actually passed away while on one of those tours on July 4, 2019. These were amazing women. Would that we could all forgive in such a manner.

Using prisoners-of-war as free labor in the concentration camps was not an unheard of practice during World War II. Many of the prisoners in Auschwitz were forced to do administrative and labor duties, such as sorting new arrivals’ possessions, constructing and expanding the camps, and taking photos of the other captives. In the photo lab at Auschwitz alone, nearly 39,000 prison photographs were taken. The problem with those photos was that when the Nazis began to realize that they were going to lose the war, they knew that all those photos were proof positive of their guilt in the matter of the Holocaust. That meant that the photos had to be destroyed.

Using prisoners-of-war as free labor in the concentration camps was not an unheard of practice during World War II. Many of the prisoners in Auschwitz were forced to do administrative and labor duties, such as sorting new arrivals’ possessions, constructing and expanding the camps, and taking photos of the other captives. In the photo lab at Auschwitz alone, nearly 39,000 prison photographs were taken. The problem with those photos was that when the Nazis began to realize that they were going to lose the war, they knew that all those photos were proof positive of their guilt in the matter of the Holocaust. That meant that the photos had to be destroyed.

During the evacuation of Auschwitz in 1945, photo lab workers Wilhelm Brasse and Bronislaw Jureczek were ordered to burn all photographic evidence. The men knew that to do so would mean that the Nazis would get away with the heinous murders they had committed. So, they came up with a way to save the pictures. They placed wet photo paper at the bottom of the furnace before placing the real pictures inside. With the furnace so packed and the wet paper creating so much smoke, the blaze went out quickly. Then, once they were unsupervised, the men were able to take the unharmed pictures from the furnace to smuggle them out. The precious pictures of victims of the Holocaust were then cataloged, and have been kept in the Archives of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.

On July 11, 1944, evidence of mass murder of Jews at the extermination camp was provided to Winston Churchill by four escapees from Auschwitz. For two years, the Nazis had managed to keep the gas chambers in Auschwitz, southern Poland, a secret. Churchill wrote to his Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, “There is no doubt this is probably the greatest and most horrible crime ever committed in the whole history of the world…all concerned in this crime who may fall into our hands, including people who only obeyed orders by carrying out the butcheries, should be put to death.”

Auschwitz was the principal Nazi extermination camp in World War II. The complex covered at least 15 square miles. As World War II was coming to a close, and the Nazis were fleeing their own demise, the camp was evacuated, there were about 67,000 inmates who were still alive there. About 56,000 of these are led away. The rest were too sick to move, so they were left behind to die. As many as 250,000 people will die on the roads before the end of the war. Originally, the site for Auschwitz was chosen because the main railway lines from Germany and Poland passed through the area. By taking the prisoners to Poland, the Nazis hoped to keep their existence a secret. When the prisoners were sent to Auschwitz, they actually had to pay their own way…to be stuffed into a cattle car, so tightly that they couldn’t even fall down if they passed out or died. Prisoners deported to Auschwitz went there to die. The Nazis had no plans for them to survive. Auschwitz contained five crematoria, made and patented by German engineering company Töpf and Sons. It was estimated that they could dispose of 4,756 corpses a day. The crimes against humanity that had been committed here were atrocious, and panic had set in among the SS guards, who feared for their lives at the hands of the ruthless Red Army when it arrived.

For the prisoners, the end was also in sight, either by death, or by liberation for the few survivors of one of humanity’s most vile atrocities. The snow across the grounds of Auschwitz was deep, and temperatures are well below freezing. The Soviet Red Army was only a few miles away. Many SS officers and their families had already left, with cases full of valuables stolen from murdered inmates. Those on the death marches from Auschwitz survived by eating the snow on the shoulders of the people in front of them, because if they bent down to pick up the slush they risked being shot. As the prisoners marched slowly west through Poland, SS Lieutenant Colonel Rudolf Höss was heading in the opposite direction. Höss had been given the task of building Auschwitz by Himmler and had been the camp’s brutal commandant, living in luxury with his wife and five children just 100 yards from the camp grounds. After consideration, he headed back to Auschwitz, past what he described as “stumbling columns of corpses,” to make sure all evidence linking him to the genocide had been destroyed. But Höss was forced to turn his car around as the Russians advanced toward him. In 1946, he was captured and a year later hanged at Auschwitz.

Inmates, Brasse and Jureczek employed at Auschwitz’s Identification Service saved the thousands of negatives

of prisoners’ ID photographs, at great personal risk to themselves, and because they did, at least some of the guilty ones could be held accountable. The photos were intended to be a way to identify prisoners if they escaped, but their rapid starvation made these images useless. Nevertheless, Brasse and Jureczek were keen on preserving evidence of the atrocities at Auschwitz, and in the end, their efforts paid off.

of prisoners’ ID photographs, at great personal risk to themselves, and because they did, at least some of the guilty ones could be held accountable. The photos were intended to be a way to identify prisoners if they escaped, but their rapid starvation made these images useless. Nevertheless, Brasse and Jureczek were keen on preserving evidence of the atrocities at Auschwitz, and in the end, their efforts paid off.

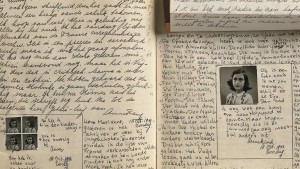

On June 12, 1942, Anne Frank, was a young Jewish girl living in Amsterdam. It was her thirteenth birthday, and as a gift, she was given a diary. Diaries have long been a big deal for girls. I know very few of those in my generation who didn’t have one. Most of those who received them, did little with them. I know that my diary (which I still have, by the way) contains mostly the gibberish of a young girl…mostly bored with the idea of journaling the meager events of my life…or at least that is how I saw them at the time. Looking back, I wish I had maybe taken the whole journaling/diary thing more seriously, because my life, while not as intense as that of Anne Frank, did have meaning, and those events that might have been considered important to my children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren have been, for the most part, lost to the forgetfulness of childhood.

On June 12, 1942, Anne Frank, was a young Jewish girl living in Amsterdam. It was her thirteenth birthday, and as a gift, she was given a diary. Diaries have long been a big deal for girls. I know very few of those in my generation who didn’t have one. Most of those who received them, did little with them. I know that my diary (which I still have, by the way) contains mostly the gibberish of a young girl…mostly bored with the idea of journaling the meager events of my life…or at least that is how I saw them at the time. Looking back, I wish I had maybe taken the whole journaling/diary thing more seriously, because my life, while not as intense as that of Anne Frank, did have meaning, and those events that might have been considered important to my children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren have been, for the most part, lost to the forgetfulness of childhood.

Many of us have heard of, read about, or seen the movie about the events of Anne Frank’s short life. One short month after receiving her diary, Anne and her family went into hiding from the Nazis in rooms behind her father’s office. Anne’s sister, Margot, received a call-up notice around 3pm on July 5, 1942. The Frank family had planned to go into hiding on July 16, 1942, but they decided to leave immediately so that Margot would not have to be deported to a “work camp.” The family left a false trail indicating that they had gone into hiding in Switzerland. According to Anne’s diary, Margot kept a diary of her own, but no trace of Margot’s diary has ever been found. This and her time in the hands of the Nazis was the main period of her diary, because as we know, Anne did not survive the Holocaust into which she and her family had been dragged. The hiding place was not discovered immediately, of course, and for the next two years, the Franks and four other families were hidden, fed, and cared for by Gentile friends. They lived in an annex, whose entrance was hidden behind a moveable bookcase. Following a tip in 1944, the families were discovered by the Gestapo. The Franks were taken to Auschwitz, where Anne’s mother died. Friends in Amsterdam searched the rooms and found Anne’s diary hidden away. They had hoped to save any personal items, so they could be returned to the family, should any of them survive.

Anne and her sister were sent to another camp, Bergen-Belsen, where Anne died a month before the war ended. Anne’s father survived Auschwitz, and after much soul searching, he published Anne’s diary in 1947 as “The Diary of a Young Girl.” The book has been translated into more than 60 languages. Had it not been for World War II, the Holocaust, and Anne’s tragic death from Typhus in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in February 1945, the diary would have most likely have been published, or even written in the way that it was.

The reality is that most diaries aren’t immensely interesting. Most are written by young girls with drama queen emotions, who are bored with their lives, because they are certain that nothing cool happens. Anne’s diary was interesting, because she wasn’t sure how long her life would be, and she wanted to know everything…before it was too late.

The reality is that most diaries aren’t immensely interesting. Most are written by young girls with drama queen emotions, who are bored with their lives, because they are certain that nothing cool happens. Anne’s diary was interesting, because she wasn’t sure how long her life would be, and she wanted to know everything…before it was too late.

The Third Reich was filled with people who were nothing less than monsters. Klaus Barbie, the former Nazi Gestapo chief of German-occupied Lyon, France, was one of them. As chief of the secret police in Lyon, Barbie sent 7,500 French Jews and French Resistance partisans to concentration camps, and executed some 4,000 others. He, like the other Nazi officers had no compassion…just a heart filled with hatred. Barbie wasn’t happy with just having them killed, he personally tortured and executed many of his prisoners himself. In 1943, he captured Jean Moulin, the leader of the French Resistance, and had him slowly beaten to death. He took pleasure in the suffering of that good man. In 1944, Barbie rounded up 44 young Jewish children and their seven teachers hiding in a boarding house in Izieu and deported them to the Auschwitz extermination camp. Of the 51 people deported, only one teacher survived. In August 1944, as the Germans prepared to retreat from Lyon, he organized one last deportation train that took hundreds of people to the death camps. He didn’t want to “lose” a single one to the liberation.

The Third Reich was filled with people who were nothing less than monsters. Klaus Barbie, the former Nazi Gestapo chief of German-occupied Lyon, France, was one of them. As chief of the secret police in Lyon, Barbie sent 7,500 French Jews and French Resistance partisans to concentration camps, and executed some 4,000 others. He, like the other Nazi officers had no compassion…just a heart filled with hatred. Barbie wasn’t happy with just having them killed, he personally tortured and executed many of his prisoners himself. In 1943, he captured Jean Moulin, the leader of the French Resistance, and had him slowly beaten to death. He took pleasure in the suffering of that good man. In 1944, Barbie rounded up 44 young Jewish children and their seven teachers hiding in a boarding house in Izieu and deported them to the Auschwitz extermination camp. Of the 51 people deported, only one teacher survived. In August 1944, as the Germans prepared to retreat from Lyon, he organized one last deportation train that took hundreds of people to the death camps. He didn’t want to “lose” a single one to the liberation.

Like all cowards, Barbie returned to Germany after the war, and began his disguise. He burned off his SS identification tattoo and assumed a new identity. This was planned as the Germans began to realize that they had lost the war. The plan was to smuggle these former SS officers out of the country, so they could “regroup later, and start the Third Reich or a facsimile of it in the future. After the Americans offered him money and protection in exchange for his intelligence services, Barbie surrendered himself to the US Counter-Intelligence Corps (CIC) and engaged in underground anti-communist activity in June 1947. Barbie worked as a US agent in Germany for two years, and the Americans shielded him from French prosecutors trying to track him down.  That frustrates me, but I suppose they figured it was the lesser of the two evils. They could go after the “bigger fish” in the organization. In 1949, Barbie and his family were smuggled by the Americans to South America.

That frustrates me, but I suppose they figured it was the lesser of the two evils. They could go after the “bigger fish” in the organization. In 1949, Barbie and his family were smuggled by the Americans to South America.

Once he was in Bolivia, Barbie assumed the name of Klaus Altmann. He settled in Bolivia and continued his work as a US agent. He became a successful businessman and advised the military regimes of Bolivia. In 1971, the oppressive dictator Hugo Banzer Suarez came to power, and Barbie helped him set up brutal internment camps for his many political opponents. During his 32 years in Bolivia, Barbie also served as an officer in the Bolivian secret police, participated in drug-running schemes, and founded a rightist death squad. He regularly traveled to Europe, and even visited France, where he had been tried in absentia in 1952 and 1954 for his war crimes and sentenced to death. He was so bold, thinking that he was invincible, but as it is in most criminals, they get careless. In 1972, the Nazi hunters Serge Klarsfeld and Beatte Kunzel discovered Barbie’s whereabouts in Bolivia, but Banzer Suarez refused to extradite him to France.

In the early 1980s, a liberal Bolivian regime came to power and agreed to extradite Barbie in exchange for French aid. His protection gone, on January 19, 1983, Barbie was arrested. He arrived in France on February 7, 1983. Unfortunately, the statute of limitations had expired on his in-absentia convictions from the 1950s. He was going to have to be tried again. At this point, the United States government formally apologized to France for its conduct in the Barbie case later that year. Even then, because of legal wrangling between the groups representing his victims, the trial was delayed for four years. Finally, on May 11, 1987, the “Butcher of Lyon,”  as he was known in France, went on trial for his crimes against humanity. His defense attorneys, three minority lawyers…an Asian, an African, and an Arab, actually made the dramatic case that the French and the Jews were as guilty of crimes against humanity as Barbie or any other Nazi. That was a completely unbelievable atrocity of a defense. Barbie’s lawyers seemed more intent on putting France and Israel on trial than in proving their client’s innocence. Their efforts failed and on July 4, 1987, he was found guilty. For his crimes, the 73-year-old Barbie was sentenced to France’s highest punishment…to spend the rest of his life in prison. He died of cancer in a prison hospital in 1991.

as he was known in France, went on trial for his crimes against humanity. His defense attorneys, three minority lawyers…an Asian, an African, and an Arab, actually made the dramatic case that the French and the Jews were as guilty of crimes against humanity as Barbie or any other Nazi. That was a completely unbelievable atrocity of a defense. Barbie’s lawyers seemed more intent on putting France and Israel on trial than in proving their client’s innocence. Their efforts failed and on July 4, 1987, he was found guilty. For his crimes, the 73-year-old Barbie was sentenced to France’s highest punishment…to spend the rest of his life in prison. He died of cancer in a prison hospital in 1991.

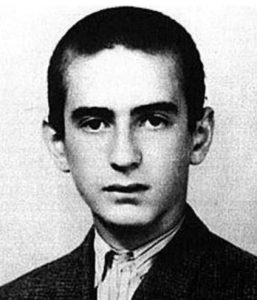

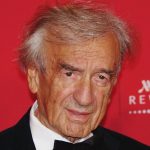

When we look at the events of the Holocaust, we find ourselves looking through the eyes of those who were resigned to their fate. Some even felt like this was what they were born for and nothing could possibly change that. One Holocaust survivor, Eliezer “Elie” Wiesel, who was born in Sighet, Romania, on September 30, 1928 expressed that very sentiment concerning his time as a prisoner of the Nazi Regime. Wiesel’s early life was fairly normal, as it was a fairly peaceful time for the Jewish people. He was part of an average Jewish family consisting of his mother, father, and three sisters, but all that came to a screeching halt in 1944, when they were shipped off to the Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland. The Holocaust experience was so horrific and such an assault on both his body and mind, that it defined his life. He couldn’t even stand to talk about much of it for over 60 years.

When we look at the events of the Holocaust, we find ourselves looking through the eyes of those who were resigned to their fate. Some even felt like this was what they were born for and nothing could possibly change that. One Holocaust survivor, Eliezer “Elie” Wiesel, who was born in Sighet, Romania, on September 30, 1928 expressed that very sentiment concerning his time as a prisoner of the Nazi Regime. Wiesel’s early life was fairly normal, as it was a fairly peaceful time for the Jewish people. He was part of an average Jewish family consisting of his mother, father, and three sisters, but all that came to a screeching halt in 1944, when they were shipped off to the Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland. The Holocaust experience was so horrific and such an assault on both his body and mind, that it defined his life. He couldn’t even stand to talk about much of it for over 60 years.

Wiesel, when he could finally speak of the atrocious acts he and others were subjected to, told of how the Nazi Regime conditioned the prisoners in the camps to believe that their future was what it was, and that they had no say in it. When his own father was beaten in front of him, Wiesel just stood there. He was horrified, but he didn’t move…he didn’t dare. For years that life moment haunted him. His father told him that it wasn’t so bad, but as his father’s son, Wiesel knew he should have done something. Nevertheless, he like so many other Jewish prisoners of the Nazi Regime, was made to understand that the killer (Nazis) came to kill, and the victim (Jews) came to be killed…like it was their destiny from the beginning of time. Somehow they were taught that this was the reason they were born. They are expected to believe that that their life had no other purpose, and that their voice didn’t matter…that their lives didn’t matter.

Wiesel’s ordeal really began in 1940, at age 12, when Hungary, which was in alliance with Nazi Germany, annexed his hometown of Sighet, Romania…although he didn’t know it then. At first things seemed ok, but then all the Jews in the city were forced into a ghetto. This was the story so many Jews shared. By 1944, when Elie was 15, Hungary colluded with Germany to deport all residents of the ghetto to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, in Poland. They were trucked out of their homes, their possessions stolen, and then they were packed into a cattle car on a train. It was so tight that they had to stand up the whole trip. They had no food or water, and no restroom facilities. It was terribly degrading. Upon arrival at Auschwitz, Elie’s mother, Sarah, and youngest sister, Tzipora, were killed, and he and his father, Shlomo, were separated from his other sisters, Hilda and Beatrice. Elie and Shlomo were transferred to Buchenwald concentration camp, where his father died.

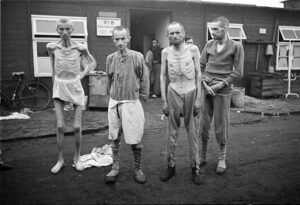

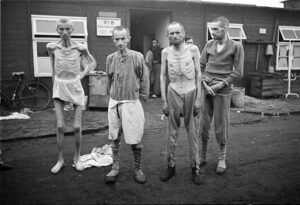

Then came some of the worst scenes he can remember. Wiesel describes it this way: “Not far from us, flames, huge flames, were rising from a ditch. Something was being burned there. A truck drew close and unloaded its hold: small children. Babies! Yes, I did see this, with my own eyes…children thrown into the flames. (Is it any wonder that ever since then, sleep tends to elude me?)” Wiesel battled with immense guilt and the ugliness of humanity for most of his life after surviving the Holocaust. Nevertheless, Wiesel was devoted to combating indifference, intolerance, and injustice. He became an accomplished writer, professor, and overall champion for human rights. Finally on April 16, 1945, American military personnel liberated the Buchenwald concentration camp. The survivors were barely alive, and even solid food ran the risk of causing their death, because their digestive systems were not prepared for much food, even though they were starving. The soldiers didn’t know the consequences, and gave them chocolate bars. The results were disastrous. They finally had to stop giving them anything, which was just as hard, if not harder than the problems caused by feeding them.

Thinking his family was gone, Wiesel eventually made his way to Paris, where he enrolled in the Sorbonne to study literature, philosophy, and psychology. By age 19, he was working as a journalist for a French newspaper, earing $16 per month…a pretty goo wage in those days. A few years later, in 1949, he was sent to Israel, to cover the early days of the new nation. Wiesel found out that two of his sisters survived, when his sister, Hilda saw his picture in a newspaper. While Elie was living in a French orphanage in 1947, a journalist took his photo, and it was published in the French newspaper where Hilda saw it. In an interview in 2000, Wiesel admitted he thought all his sisters had died in the Holocaust. “When I was still in Buchenwald, I studied the lists of survivors, and my sisters’ names were not there. That’s why I went to France…otherwise I would have gone back to my hometown of Sighet. In France, a clerk in an office at the orphanage told me that he had talked with my sister, who was looking for me. ‘That’s impossible!’ I told him. ‘How would she even know I am in France?’ But he insisted that she’d told him that she would be waiting for me in Paris the next day. I didn’t sleep that night. The next day, I went to Paris, and there was my older sister! After our liberation, she had

gotten engaged and gone to France, because she thought I was dead too. Then one day she opened the paper and saw my picture [a journalist had come to the orphanage to take pictures and write a story]. If it hadn’t been for that, it may have been years before we met. My other sister had gone back to our hometown after our release, thinking that I might be there.” The following year, Elie reunited with Beatrice, in Antwerp, Belgium. She eventually emigrated to Canada, where she lived for the rest of her life. Elie Wiesel passed away on July 2, 2016.

gotten engaged and gone to France, because she thought I was dead too. Then one day she opened the paper and saw my picture [a journalist had come to the orphanage to take pictures and write a story]. If it hadn’t been for that, it may have been years before we met. My other sister had gone back to our hometown after our release, thinking that I might be there.” The following year, Elie reunited with Beatrice, in Antwerp, Belgium. She eventually emigrated to Canada, where she lived for the rest of her life. Elie Wiesel passed away on July 2, 2016.

Primo Levi was an Italian Jew born on July 31, 1919 at Corso Re Umberto 75 in Turin, Italy, to Jewish parents Cesare and Esther “Rina” Levi. His father worked for the manufacturing firm Ganz and spent much of his time working abroad in Hungary, where Ganz was based. Levi’s mother was well educated, having attended the Istituto Maria Letizia. Rina and Cesare’s marriage was arranged by Rina’s father, Cesare Luzzati, who gave the young couple the apartment at Corso Re Umberto as a wedding gift. Primo Levi lived there for almost his entire life.

Primo Levi was an Italian Jew born on July 31, 1919 at Corso Re Umberto 75 in Turin, Italy, to Jewish parents Cesare and Esther “Rina” Levi. His father worked for the manufacturing firm Ganz and spent much of his time working abroad in Hungary, where Ganz was based. Levi’s mother was well educated, having attended the Istituto Maria Letizia. Rina and Cesare’s marriage was arranged by Rina’s father, Cesare Luzzati, who gave the young couple the apartment at Corso Re Umberto as a wedding gift. Primo Levi lived there for almost his entire life.

Primo Levi was an intelligent young man who excelled in school. In September 1930 he entered the Massimo d’Azeglio Royal Gymnasium a year ahead of normal entrance requirements. In class he was the youngest, the shortest and the most clever…he was also the only Jew. All this brought as its reward constant bullying. In August 1932, following two years at the Talmud Torah school in Turin, he sang in the local synagogue for his Bar Mitzvah. In 1933, he joined the Avanguardisti movement for young Fascists, as was expected of all young Italian schoolboys. He never wanted to be a soldier, so he avoided rifle drill by joining the ski division, and spent every Saturday during the season on the slopes above Turin. As a young boy Levi was plagued by illness, particularly chest infections, but he was keen to participate in physical activity. In his teens, Levi and a few friends would sneak into a disused sports stadium and conduct athletic competitions.

Levi later became a scientist, and it was this decision that would save his life during the Holocaust years…so to speak. When the deportations began, Levi found himself on a train to Auschwitz…the notorious death camp. The prisoners were put through a rigorous selection process. Those who didn’t make the cut, went directly to  the gas chambers. The rest were placed into forced labor…a harsh back-breaking labor with starvation level rations.

the gas chambers. The rest were placed into forced labor…a harsh back-breaking labor with starvation level rations.

Surviving the initial selection process at Auschwitz merely qualified a prisoner to be assigned to extremely harsh conditions involving back-breaking labor and intentionally miniscule amounts of nourishment. Levi was different. He was considered “useful” to the Nazis. His expertise as a scientist got him assigned in the camp laboratory. It also got him better food rations. Many would consider him lucky, but there was a price to pay for such luck. Levi was spared the horrific treatment his fellow prisoners were subjected to, but his protection from actually being subjected to such treatment did not save him from the horrors of witnessing such treatment. Levi tells the story of how prisoners at Auschwitz were treated in the books he has written on the subject. He tells of periodic selections, in which prisoners were forced to strip naked. These inspections were to “weed out” prisoners who were too exhausted or sick to provide meaningful labor. These prisoners were designated for transport to Auschwitz-Birkenau and the gas chamber. The prisoners who had been at Auschwitz…unlike newer prisoners, knew exactly what awaited them.

Levi’s description of this process from his work “The Drowned and the Saved” explains how most were already too mentally defeated and humiliated to resist: “The day in the [camp] was studded with innumerable harsh strippings – checking for lice, searching one’s clothes, examining for scabies and then the morning wash-up – as well as for the periodic selections, during which a ‘commission’ decided who was still fit for work and who, on the contrary, was marked for elimination. Now a naked and barefoot man feels that all his nerves and tendons are severed: He is helpless prey. Clothes, even the foul clothes distributed, even the crude clogs with their  wooden soles, are a tenuous but indispensable defense. Anyone who does not have them no longer perceives himself as a human being but rather as a worm: naked, slow, ignoble, prone on the ground. He knows that he can be crushed at any moment.”

wooden soles, are a tenuous but indispensable defense. Anyone who does not have them no longer perceives himself as a human being but rather as a worm: naked, slow, ignoble, prone on the ground. He knows that he can be crushed at any moment.”

Levi survived his ordeal in Auschwitz, one of the few that did, but that did not ensure a quiet peaceful life for him. On April 11, 1987, Primo Levi died after a fall from a three-story building. His death was ruled a suicide, which would not be surprising with “survivor’s guilt” syndrome, but there are many who don’t believe that Levi would have committed suicide, and they think his death was an accident. I don’t suppose we will ever know, but I believe that whatever happened, Primo Levi is finally at peace.

Many people have tattoos these days, and the shops that perform their arts for people, have to comply with strict and sanitary working conditions. A tattoo performed in unsanitary conditions can become infected, and cause the loss of limb or even life, if it is not caught in time. The artwork these days is intricate and very elaborate. People can customize their tattoo so as to reflect their own personality. These days a tattoo is something lots of people use to express themselves, but tattoos were not always considered a thing of beauty, and was often forced upon people. Never was this more forced than during the Holocaust against the Jews.

Many people have tattoos these days, and the shops that perform their arts for people, have to comply with strict and sanitary working conditions. A tattoo performed in unsanitary conditions can become infected, and cause the loss of limb or even life, if it is not caught in time. The artwork these days is intricate and very elaborate. People can customize their tattoo so as to reflect their own personality. These days a tattoo is something lots of people use to express themselves, but tattoos were not always considered a thing of beauty, and was often forced upon people. Never was this more forced than during the Holocaust against the Jews.

Maria Ossowski was a Polish member of the Resistance imprisoned in Auschwitz in 1943. So many people did not survive, but those who did have lived to tell the truth about the Final Solution…Hitler’s most evil plot and crimes against humanity. Ossowski later recalled the horrible first few minutes of captivity and the tattooing process in the camp. Those people who did not die on the trains, or who were not herded straight to the gas chambers were herded into what they were told was their washroom. Ossowski says, “It was a huge barrack, with the water running, cold water I must add, from the top, there were men in already prison garb, which we never seen before. We were made to strip, we were made to go in front – each one of us – in front of that man, that man or the other one, they were all standing in the line, and we were shaven – we were shaven – our heads were shaven, our private parts were shaven and we were pushed then under that water. And after a while we were pushed out of it into another part of that big block, where the huge amount of terrible-looking – and already smelling terrible – clothes were prepared for us.”

Then they were given one dress with three-quarter sleeves that was put on over their heads. Once they were dressed, they were herded into another part, where female prisoners were sitting by little tables. Each had a job to do. They were to tattoo numbers on each prisoner’s arm. The tattoo process was not done in sanitary conditions, but it was done with an instrument that basically “wrote” the number into their arm. The instrument cut the skin and pushed ink under the skin. Ballpoint pens were not invented then, but the tool used acted in a

similar way. The process continued until the point and ink formed the shape of a number. Originally a sharp stamp was used, but it was impractical, and so they used the needle and ink method. Those who did receive a tattoo on arrival at Auschwitz might actually be considered “lucky” in that only those deemed fit for work were tattooed. The others were sent off for immediate execution. I doubt anyone who carried this forced tattoo considered it lucky.

similar way. The process continued until the point and ink formed the shape of a number. Originally a sharp stamp was used, but it was impractical, and so they used the needle and ink method. Those who did receive a tattoo on arrival at Auschwitz might actually be considered “lucky” in that only those deemed fit for work were tattooed. The others were sent off for immediate execution. I doubt anyone who carried this forced tattoo considered it lucky.

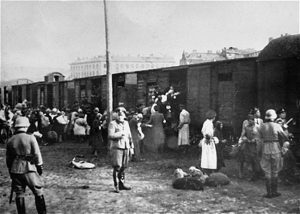

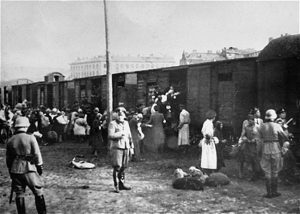

When Hitler decided that the time in his “final solution” had come to transport the Jews, Gypsies, and other “undesirables” to the death camps, he chose to transport them in cattle cars on a train. Hitler had so little compassion for human life, that when the people were loaded into the cattle cars, they were packed in tightly with as many 80 people to a car. They couldn’t sit down. The air was stifling. The trains didn’t stop for bathroom breaks or food. The people had to stand there hour after hour, for up to four very long days. Hitler and his men didn’t care, they didn’t even consider the people to be human, and to make matters worse, they thought it a good thing if the people just died en route, because it would save them the hassle, ammunition, and poison needed to kill them later.

When Hitler decided that the time in his “final solution” had come to transport the Jews, Gypsies, and other “undesirables” to the death camps, he chose to transport them in cattle cars on a train. Hitler had so little compassion for human life, that when the people were loaded into the cattle cars, they were packed in tightly with as many 80 people to a car. They couldn’t sit down. The air was stifling. The trains didn’t stop for bathroom breaks or food. The people had to stand there hour after hour, for up to four very long days. Hitler and his men didn’t care, they didn’t even consider the people to be human, and to make matters worse, they thought it a good thing if the people just died en route, because it would save them the hassle, ammunition, and poison needed to kill them later.

I suppose that for Hitler and the Nazis, the plan was one of simple logistics of transporting millions of people to southern Poland. Some of the people came from as far away as the Netherlands, France, Italy, and Greece. Transportation was done occasionally in passenger trains, in which wealthy Jews were encouraged to bring as much of their wealth with them as possible. Oh course, the Jews thought they would be able to keep their belongings, but in reality, this was railway robbery, because their wealth was soon to be transferred to the Nazis. Where they were going, they would not need their property.

The transports of the Jews to Auschwitz went of daily, on schedule. They leave from the ghetto embarkation depots, on schedule. The process was very methodical…almost mechanical, or robotic. Those in charge had no compassion for the people being herded into the cattle cars. The conductors signaled, “All aboard.” The brakemen waved lanterns. Anyone who resisted was shot by German and Hungarian guards. Guards used clubs and bayonets to herd a last group of mothers into the compartments. Finally, the engineer opens the throttle, and right on schedule, the train is off for Auschwitz.

Eighty Jews in every compartment was the average, but Eichmann boasted that the Germans could do better where there were more children. With the children in the groups, they could jam 120 into each train room. The Jews had to stand all the way to Auschwitz…with their hands raised in the air…because that made room for the maximum number of passengers. Each compartment had two buckets…one containing water, and the other to use as a toilet, to be shoved by foot, if possible, from user to user, not that anyone could use their hands to facilitate waste elimination. Many just had to relieve themselves where they stood, through their clothing. The water buckets made no sense either, because one water bucket for over eighty people for four days, would never be enough, if they could figure out a way to get the water from the bucket to their mouths. Still, no one could say the Nazis were cruel…after all, the buckets were there, right? In the four days that it took to get to Auschwitz, many, if not all of the prisoners were dead, standing up, because in the tight quarters, the dead

could not even fall. Those who survived were to face an worse fate than dying on the train. They faced slavery, forced experimentation, and finally the gas chambers. Children were separated from parents, men from women, and the elderly simply sent straight to the gas chambers. People were mutilated, poisoned, beaten, forced to stand outside naked in the bitter cold of winter or in the heat of summer, crammed into quarters with no heat or blankets, and starved to death on a mere 700 calories or less a day. Death was the best option.

could not even fall. Those who survived were to face an worse fate than dying on the train. They faced slavery, forced experimentation, and finally the gas chambers. Children were separated from parents, men from women, and the elderly simply sent straight to the gas chambers. People were mutilated, poisoned, beaten, forced to stand outside naked in the bitter cold of winter or in the heat of summer, crammed into quarters with no heat or blankets, and starved to death on a mere 700 calories or less a day. Death was the best option.