antietam

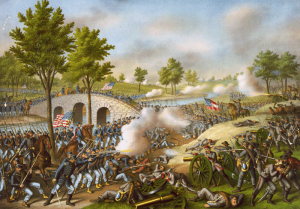

These days, with the many types of bombs nations use for warfare, it would be easy to annihilate an entire town, but during the Civil War…not so much. One bomb dropped on Hiroshima instantly killed 80,000 people. Of course that was on August 6, 1945, and not 1862. September 17, 1862 dawned slowly through the fog. It seemed like the start of a peacefully beautiful day, but looks can be deceiving. That morning, the soldiers were busy, trying to wipe away the dampness, when cannons began to roar and sheets of flame burst forth from hundreds of rifles. The bloodiest one-day battle in American History had begun. The Battle of Antietam was a 12-hour battle that swept across the rolling farm fields in western Maryland. It was this battle between North and South that changed the course of the Civil War, helped free over four million Americans, devastated Sharpsburg, and no other one-day battle would be as bloody.

These days, with the many types of bombs nations use for warfare, it would be easy to annihilate an entire town, but during the Civil War…not so much. One bomb dropped on Hiroshima instantly killed 80,000 people. Of course that was on August 6, 1945, and not 1862. September 17, 1862 dawned slowly through the fog. It seemed like the start of a peacefully beautiful day, but looks can be deceiving. That morning, the soldiers were busy, trying to wipe away the dampness, when cannons began to roar and sheets of flame burst forth from hundreds of rifles. The bloodiest one-day battle in American History had begun. The Battle of Antietam was a 12-hour battle that swept across the rolling farm fields in western Maryland. It was this battle between North and South that changed the course of the Civil War, helped free over four million Americans, devastated Sharpsburg, and no other one-day battle would be as bloody.

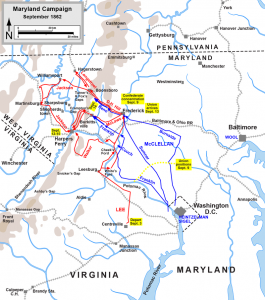

The Battle of Antietam marked the first invasion into the North by Confederate General Robert E Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. It was the culmination of the Maryland Campaign of 1862. Southern armies were also advancing in Kentucky and Missouri, as the tide of war flowed north. After Lee’s dramatic victory at the Second Battle of Manassas during the last two days of August, he wrote to Confederate President Jefferson Davis that “we cannot afford to be idle.” Lee wanted to keep the pressure on in order to secure Southern independence through victory in the North; influence the Fall mid-term elections; obtain much-needed supplies; move the war out of Virginia, possibly into Pennsylvania; and to liberate Maryland, a Union state, but a slave-holding border state divided in its values.

Lee’s army splashed across the Potomac River and arrived in Frederick, Virginia, where he boldly divided his army to capture the Union garrison stationed at Harpers Ferry. A vital location on the Confederate lines of supply and communication back to Virginia; Harpers Ferry, Maryland was the gateway to the Shenandoah Valley. Lee’s link to the south was threatened by the 12,000 Union soldiers at Harpers Ferry. General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson and about half of the Army of Northern Virginia were sent to capture Harpers Ferry. The rest of the Confederates moved north and west toward South Mountain and Hagerstown, Maryland. The Confederate army soon retreated from South Mountain, and Lee considered returning to Virginia. However, with Jackson’s capture of Harpers Ferry on September 15th, Lee decided to make a stand at Sharpsburg.

Lee gathered his forces on the high ground west of Antietam Creek, with General James Longstreet’s command holding the center and the right, while Jackson’s men filled in on the left. The Confederate position was strengthened with the mobility provided by the Hagerstown Turnpike that ran north and south along Lee’s line. Still, the Potomac River behind them and only one crossing back to Virginia remained a risk. Lee and his men watched the Union army gather on the east side of Antietam Creek. Thousands of soldiers in blue marched into position throughout September 15th and 16th as General McClellan prepared for his attempt to drive Lee from Maryland. McClellan’s plan was to “attack the enemy’s left” and when “matters looked favorably,” attack the Confederate right, and “whenever either of those flank movements should be successful to advance our center.” As the opposing forces moved into position during the rainy night of September 16th, one Pennsylvanian remembered, “…all realized that there was ugly business and plenty of it just ahead.”

The twelve-hour battle began at dawn, and for the next seven hours, there were three major Union attacks on the Confederate left, moving from north to south. General Joseph Hooker’s command led the first Union assault. General Joseph Mansfield’s soldiers attacked second, followed by General Edwin Sumner’s men as McClellan’s plan broke down into a series of uncoordinated Union advances. The fierce battle raged across the Cornfield, East Woods, West Woods, and the Sunken Road as Lee shifted his men to withstand each of the Union thrusts. After clashing for over eight hours, Lee’s troops were pushed back, but not broken. Shockingly, over 15,000 soldiers were killed or wounded.

While the Union assaults were being made on the Sunken Road, a mile-and-a-half farther south, Union General Ambrose Burnside opened the attack on the Confederate right. He first sought to capture the bridge that would later bear his name, but a small Confederate force, positioned on higher ground, was able to delay Burnside for three hours. Finally, about 1:00pm Burnside captured the bridge, and then reorganized for two hours before moving forward across the difficult terrain…an unfortunate delay. When the advance did begin, it was turned back by Confederate General AP Hill’s reinforcements, who had arrived in the late afternoon from Harpers Ferry.

Neither flank of the Confederate army collapsed far enough for McClellan to advance his center attack, leaving a sizable Union force that never entered the battle. Despite an estimated 23,100 casualties of the nearly 100,000 engaged, both armies stubbornly held their ground as the sun set on the devastated landscape. The next day, September 18, 1862, the opposing armies gathered their wounded and buried their dead. That night  General Robert E Lee’s army withdrew back across the Potomac River to Virginia, ending his first invasion into the North. Lee’s retreat to Virginia provided President Abraham Lincoln the opportunity he had been waiting to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Now, the Civil War had a dual purpose of preserving the Union and ending slavery, which the United States had been trying to end since it was founded.

General Robert E Lee’s army withdrew back across the Potomac River to Virginia, ending his first invasion into the North. Lee’s retreat to Virginia provided President Abraham Lincoln the opportunity he had been waiting to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Now, the Civil War had a dual purpose of preserving the Union and ending slavery, which the United States had been trying to end since it was founded.

The Battle of Antietam was fought over an area of 12 square miles. Today the site consists of 184 acres containing approximately 5 miles of paved avenues. Located along the battlefield avenues to mark battle positions of infantry, artillery, and cavalry are many monuments, markers, and narrative tablets. Markers describe the actions at Turner’s Gap, Harpers Ferry, and Blackford’s Ford. Key artillery positions on the field of Antietam are marked by cannon. And 10 large-scale field exhibits at important points on the field indicate troop positions and battle action.