ace

When a war begins, I doubt if anyone is thinking about the medals or the honors they might receive, because what they really want is for the war to be over already. Nobody enjoys going to war…not even the one who starts the war. There are never any guarantees that you will come out of a war alive, so most people would rather not go at all. Nevertheless, when a soldier goes into war, he or she has taken a vow to do their very best, and to fight to the death, if necessary. When World War II got started, the United States really intended to stay out of it. They vowed to stay neutral…until the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Once the United States entered World War II, however, we were in it to win it.

When a war begins, I doubt if anyone is thinking about the medals or the honors they might receive, because what they really want is for the war to be over already. Nobody enjoys going to war…not even the one who starts the war. There are never any guarantees that you will come out of a war alive, so most people would rather not go at all. Nevertheless, when a soldier goes into war, he or she has taken a vow to do their very best, and to fight to the death, if necessary. When World War II got started, the United States really intended to stay out of it. They vowed to stay neutral…until the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Once the United States entered World War II, however, we were in it to win it.

Lieutenant Edward O’Hare, an American naval aviator of the United States Navy, was born on March 13, 1914 in Saint Louis, Missouri, to Selma Anna (Lauth) and Edward Joseph O’Hare. He was of Irish and German descent. Edward, who was nicknamed “Butch,” had two sisters, Patricia and Marilyn. Their parents divorced in 1927. Butch and his sisters stayed with their mother in Saint Louis, and their father moved to Chicago. O’Hare joined the Navy, and from there, life moved pretty fast. On July 21, 1941, O’Hare met his future wife, Rita and asked her to marry him that night. He knew immediately that she was the one. They got married on September 6, 1941 and their daughter, Kathleen was born in January or February of 1943. O’Hare first met her when she was a month old, because of missions he was on.

In the Navy, O’Hare was stationed first on the USS Saratoga, then on the USS Enterprise, and then on the USS Lexington, flying a Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat. In mid-February 1942, the Lexington sailed into the Coral Sea. A town named Rabaul, at the very tip of New Britain, one of the islands that comprised the Bismarck Archipelago, had been invaded in January by the Japanese and transformed into a stronghold. In fact, it had been turned into one huge airbase. The occupation of Rabaul put the Japanese in prime striking position for the Solomon Islands, which would have been put them in a perfect position for expanding their ever-growing Pacific empire. Given the mission of destabilizing the Japanese position on Rabaul with a bombing raid, the fighters on the Lexington took off from the aircraft carrier’s deck in a raid against the Japanese position at Rabaul. Just moments later, Lieutenant O’Hare became America’s first World War II flying ace. In the battle that took place on February 20, 1942, O’Hare believed he had shot down six bombers and damaged a seventh. Captain Frederick C Sherman later reduced that number to five, as four of the reported nine bombers were still overhead when he pulled off. Nevertheless, in the opinion of Admiral Brown and of Captain Sherman, commanding the Lexington, Lieutenant O’Hare’s actions may have saved the carrier from serious damage or even loss. In a mere four minutes, O’Hare shot down five Japanese G4M1 Betty bombers, bringing a swift end to the Japanese attack and earning O’Hare the designation “Ace,” which was given to any pilot who had five or more downed enemy planes to his credit. The attack on the bombers was great, but it ruined the element of surprise, so the mission was called off.

On the night of November 26, 1943, the USS Enterprise introduced the experiment in the co-operative control of Avengers and Hellcats for night fighting. The team consisted of three planes, breaking up a large group of land-based bombers. O’Hare volunteered to lead this mission to conduct the first-ever Navy nighttime fighter

attack from an aircraft carrier to intercept a large force of enemy torpedo bombers. When the call came to man the fighters, Butch O’Hare was eating. He grabbed up part of his supper in his fist and started running for the ready room. It was to be his final mission. When it was over, O’Hare was missing in action. He was declared dead a year later. The airport in Chicago and a destroyer would later be named in his honor. He lived life fast and died young, but he was always in it to win it.

attack from an aircraft carrier to intercept a large force of enemy torpedo bombers. When the call came to man the fighters, Butch O’Hare was eating. He grabbed up part of his supper in his fist and started running for the ready room. It was to be his final mission. When it was over, O’Hare was missing in action. He was declared dead a year later. The airport in Chicago and a destroyer would later be named in his honor. He lived life fast and died young, but he was always in it to win it.

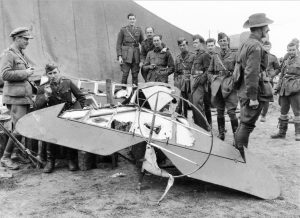

Who fired the shot that killed Richthofen? And who was Richthofen anyway? First, Richthofen was also known as the Red Baron. Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen was born on May 2, 1892. He was a fighter pilot with the German Air Force during World War I, and is considered the ace-of-aces of the war. He was officially credited with 80 air combat victories.

Who fired the shot that killed Richthofen? And who was Richthofen anyway? First, Richthofen was also known as the Red Baron. Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen was born on May 2, 1892. He was a fighter pilot with the German Air Force during World War I, and is considered the ace-of-aces of the war. He was officially credited with 80 air combat victories.

Nevertheless, as it goes with fighter pilots, their lives are always in jeopardy, and not all of them will come out of war alive. Such was the case with the Red Baron. The end came for him on April 21, 1918. It’s possible that he made mistakes on that final flight. Richthofen was a highly experienced and skilled fighter pilot, who was fully aware of the risk from ground fire. Furthermore, he concurred with the rules of air fighting created by his late mentor Boelcke, who specifically advised pilots not to take unnecessary risks. With that in mind, one must wonder if Richthofen’s judgement during his last combat was unsound or somehow compromised.

Several theories have been proposed to account for his behavior. In 1999, a German medical researcher, Henning Allmers, published an article in the British medical journal The Lancet, suggesting it was likely that brain damage from the head wound Richthofen suffered in July 1917, played a part in the Red Baron’s death. This was supported by a 2004 paper by researchers at the University of Texas. Richthofen’s behavior after his injury was noted as consistent with brain-injured patients, and such an injury could account for his perceived lack of judgement on his final flight…a flight in which he was flying too low over enemy territory and suffering target fixation, which is an attentional phenomenon observed in humans in which an individual becomes so focused on an observed object, that they inadvertently increase their risk of colliding with the object.

Still, the biggest question is not why the Red Baron made the mistake that would get him killed, but rather who killed him. The RAF credited Arthur Roy Brown, an RNAS lieutenant with shooting down the Red Baron, but it is  now generally agreed that the bullet that hit the Red Baron was fired from the ground. The Red Baron died following an extremely serious and inevitably fatal chest wound from a single bullet, penetrating from the right armpit and resurfacing from his left chest. Brown’s attack was from behind and above, and from Red Baron’s left. Even more conclusively, Red Baron could not have continued his pursuit for as long as he did…up to two minutes…had this wound come from Brown’s guns. Brown himself never spoke much about what happened that day, claiming, “There is no point in me commenting, as the evidence is already out there.”

now generally agreed that the bullet that hit the Red Baron was fired from the ground. The Red Baron died following an extremely serious and inevitably fatal chest wound from a single bullet, penetrating from the right armpit and resurfacing from his left chest. Brown’s attack was from behind and above, and from Red Baron’s left. Even more conclusively, Red Baron could not have continued his pursuit for as long as he did…up to two minutes…had this wound come from Brown’s guns. Brown himself never spoke much about what happened that day, claiming, “There is no point in me commenting, as the evidence is already out there.”

Many sources, including a 1998 article by Geoffrey Miller, a physician and historian of military medicine, and a 2002 British Channel 4 documentary, have suggested that Sergeant Cedric Popkin was the person most likely to have killed Richthofen. Popkin was an anti-aircraft (AA) machine gunner with the Australian 24th Machine Gun Company, and was using a Vickers gun. He fired at Richthofen’s aircraft on two occasions…first as the Baron was heading straight at his position, and then at long range from the right. Given the nature of Richthofen’s wounds, Popkin was in a position to fire the fatal shot, when the pilot passed him for a second time, on the right. Some confusion has been caused by a letter that Popkin wrote, in 1935, to an Australian official historian. It stated Popkin’s belief that he had fired the fatal shot as Red Baron flew straight at his position. In the latter respect, Popkin was incorrect. The bullet that caused the Baron’s death came from the side.

A 2002 Discovery Channel documentary suggests that Gunner W. J. “Snowy” Evans, a Lewis machine gunner with the 53rd Battery, 14th Field Artillery Brigade, Royal Australian Artillery is likely to have killed Red Baron.  Miller and the Channel 4 documentary dismiss this theory, because of the angle from which Evans fired at Richthofen.

Miller and the Channel 4 documentary dismiss this theory, because of the angle from which Evans fired at Richthofen.

Other sources have suggested that Gunner Robert Buie, also of the 53rd Battery, may have fired the fatal shot. There is little support for this theory. In 2007, a municipality in Sydney recognized Buie as the man who shot down Richthofen, placing a plaque near Buie’s former home. Buie, who died in 1964, has never been officially recognized in any other way. I suppose that, in reality, we will never really know for sure who killed Red Baron, but the theories present an interesting puzzle, and one that will most likely never be solved.