World War I

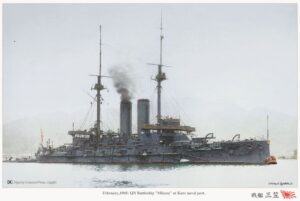

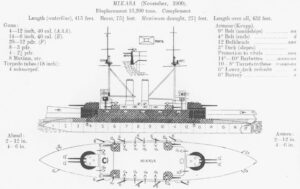

It is not usually my habit to talk about the spectacular ships built by our nation’s enemies, but IJN Mikasa might be a worthy exception. The Mikasa is a “pre-dreadnought” battleship built for the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) in the late 1890s and is the only ship of her class. I didn’t know what a “pre-dreadnought” ship was, so I looked into it. “Pre-dreadnoughts were battleships built before 1906, when HMS Dreadnought was launched. Dreadnoughts were more powerful battleships that followed the design of HMS Dreadnought and so made pre-dreadnoughts obsolete.” The ship displaced over 15,000 long tons, with a crew of over 800 men.

It is not usually my habit to talk about the spectacular ships built by our nation’s enemies, but IJN Mikasa might be a worthy exception. The Mikasa is a “pre-dreadnought” battleship built for the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) in the late 1890s and is the only ship of her class. I didn’t know what a “pre-dreadnought” ship was, so I looked into it. “Pre-dreadnoughts were battleships built before 1906, when HMS Dreadnought was launched. Dreadnoughts were more powerful battleships that followed the design of HMS Dreadnought and so made pre-dreadnoughts obsolete.” The ship displaced over 15,000 long tons, with a crew of over 800 men.

While she might not have been as powerful, IJN Mikasa was nevertheless a well-built ship, that was able to withstand more than most ships of her time. Named after Mount Mikasa in Nara, Japan, she served as the flagship of Vice Admiral Togo Heihachiro throughout the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. That war included the Battle of Port Arthur, which occurred on the second day of the war, as well as the Battles of the Yellow Sea and Tsushima. Just a few days after the Russo-Japanese War ended, Mikasa’s magazine (a ship’s magazine is where the powder and shells are stored) suddenly exploded and sank the ship. The explosion killed 251 men. Shortly before the Mikasa’s fatal accident, the ship had been involved in the  Battle of Tsushima (May 27, 1905), during which she had shrugged off over 40 shell strikes from heavy Russian naval guns! In that battle 113 of her crew were killed or injured. While such an event would usually mean the end of a ship, IJN Mikasa was salvaged, and while her repairs took over two years to complete, she went on to serve as a coast-defense ship during World War I, and she supported Japanese forces during the Siberian Intervention in the Russian Civil War. Ironically, in 1912 a despondent sailor among her crew tried to blow the ship up once again while the ship was anchored at Kobe. In the end the ship served until 1923, after being pulled up from the drink, repaired, and recommissioned.

Battle of Tsushima (May 27, 1905), during which she had shrugged off over 40 shell strikes from heavy Russian naval guns! In that battle 113 of her crew were killed or injured. While such an event would usually mean the end of a ship, IJN Mikasa was salvaged, and while her repairs took over two years to complete, she went on to serve as a coast-defense ship during World War I, and she supported Japanese forces during the Siberian Intervention in the Russian Civil War. Ironically, in 1912 a despondent sailor among her crew tried to blow the ship up once again while the ship was anchored at Kobe. In the end the ship served until 1923, after being pulled up from the drink, repaired, and recommissioned.

IJN Mikasa was decommissioned on September 23, 1923, following the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922. At that time, she was scheduled for destruction, but at the request of the Japanese government, each of the signatory countries to the treaty agreed that Mikasa could be preserved as a memorial ship. The agreement required that her hull be encased in concrete. On November 12, 1926, Mikasa was opened for display in Yokosuka in the presence of Crown Prince Hirohito and Togo. Unfortunately, the ship deteriorated under the  control of the occupation forces after the surrender of Japan in 1945. Finally, in 1955, American businessman John Rubin, who had formally lived in Barrow, England, wrote a letter to the Japan Times about the state of the ship. His letter served as the catalyst for a new restoration campaign. The Japanese public, who were widely onboard with the idea, supported the project, as did Fleet Admiral Chester W Nimitz. The ship was once again restored, and the museum version reopened in 1961. On August 5, 2009, IJN Mikasa was repainted by sailors from USS Nimitz, and she is now the only surviving example of a “pre-dreadnought” battleship in the world. IJN Mikasa is located in the town of its construction, Barrow-in-Furness, near Mikasa Street on Walney Island.

control of the occupation forces after the surrender of Japan in 1945. Finally, in 1955, American businessman John Rubin, who had formally lived in Barrow, England, wrote a letter to the Japan Times about the state of the ship. His letter served as the catalyst for a new restoration campaign. The Japanese public, who were widely onboard with the idea, supported the project, as did Fleet Admiral Chester W Nimitz. The ship was once again restored, and the museum version reopened in 1961. On August 5, 2009, IJN Mikasa was repainted by sailors from USS Nimitz, and she is now the only surviving example of a “pre-dreadnought” battleship in the world. IJN Mikasa is located in the town of its construction, Barrow-in-Furness, near Mikasa Street on Walney Island.

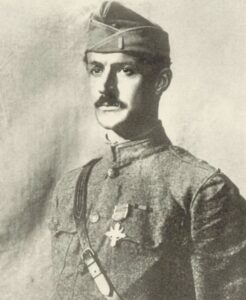

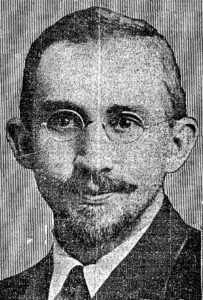

There were amazing pilots on both sides of World War I. One fighter pilot who really stood out as a superstar was Baron von Richthofen, known to the world as the Red Baron. The Red Baron was born on May 2, 1892, into a family of Prussian nobles. Growing up in the Silesia region of what is now Poland, he lived the kind of life you would expect of a nobleman. He passed the time playing sports, riding horses, and hunting wild game, a passion that would follow him for the rest of his life. As was common and on the wishes of his father, Richthofen was enrolled in military school at age 11. Many people felt that military school would provide the best discipline and training, especially if one were going to be an officer. Shortly before his 18th birthday, he was commissioned as an officer in a German cavalry unit.

There were amazing pilots on both sides of World War I. One fighter pilot who really stood out as a superstar was Baron von Richthofen, known to the world as the Red Baron. The Red Baron was born on May 2, 1892, into a family of Prussian nobles. Growing up in the Silesia region of what is now Poland, he lived the kind of life you would expect of a nobleman. He passed the time playing sports, riding horses, and hunting wild game, a passion that would follow him for the rest of his life. As was common and on the wishes of his father, Richthofen was enrolled in military school at age 11. Many people felt that military school would provide the best discipline and training, especially if one were going to be an officer. Shortly before his 18th birthday, he was commissioned as an officer in a German cavalry unit.

Richthofen transferred to the Air Service in 1915, and in 1916 he became one of the first members of fighter squadron Jagdstaffel 2. He was a natural and quickly distinguished himself as a fighter pilot. Then, in 1917 became the leader of Jasta 11. He would go on to lead the larger fighter wing Jagdgeschwader I, which was also known as “The Flying Circus” or “Richthofen’s Circus” mostly because of the bright colors of its aircraft, but maybe because of the way the unit was transferred from one area of Allied air activity to another. When units were moved, it was like a travelling circus. They moved and often set up in tents on improvised airfields.

Between September 1916 and April 1918, he shot down 80 enemy aircraft. That was more than any other pilot during World War I. The Red Baron once wrote, “I never get into an aircraft for fun. I aim first for the head of the pilot, or rather at the head of the observer, if there is one.” He was well known for his crimson-painted Albatros biplanes and Fokker triplanes, and the “Red Baron” by 1918, Richthofen was regarded as a national hero in Germany, and strangely, Richthofen was even respected by his enemies, which is very rare indeed.

Loyal to the end, Richthofen received a fatal wound while flying over Morlancourt Ridge near the Somme River, just after 11:00am on April 21, 1918. He had been pursuing, a Sopwith Camel piloted by Canadian novice Wilfrid Reid “Wop” May of the Number 209 Squadron, Royal Air Force. May had just fired on the Red Baron’s cousin, Lieutenant Wolfram von Richthofen. When he saw his cousin being attacked, the Red Baron flew rescue him. He fired on May’s plane, causing him to pull away, then he chased May across the Somme. The Baron was spotted and briefly attacked by a Camel piloted by May’s school friend and flight commander, Canadian Captain Arthur “Roy” Brown. Brown had to dive steeply at very high speed to intervene, and then had to climb steeply to avoid hitting the ground. Richthofen turned to avoid this attack, and then resumed his pursuit of May.

During this final stage in his pursuit of May, Richthofen was hit by a single .303 bullet through the chest, severely damaging his heart and lungs. He would have bled out in less than a minute. Now pilotless, the plane stalled and went into a steep dive. It hit the ground in a field on a hill near the Bray-Corbie Road, just north of the village of Vaux-sur-Somme. This was in a sector defended by the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). The plane bounced heavily when it hit the ground, and the undercarriage collapsed. The fuel tank was smashed before the aircraft skidded to a stop. Several witnesses, including Gunner George Ridgway, reached the crashed plane and found Richthofen already dead, and his face slammed into the butts of his machine guns, breaking his nose, fracturing his jaw and creating contusions on his face.

Number 3 Squadron AFC’s commanding officer Major David Blake, who was responsible for Richthofen’s body, regarded the Red Baron with great respect. It was Blake who was responsible for organizing the funeral, and he decided on a full military funeral. Richthofen’s body was buried in the cemetery at the village of Bertangles, near Amiens, on April 22, 1918. Six of Number 3 Squadron’s officers served as pallbearers, and a guard of honor from the squadron’s other ranks fired a salute. Allied squadrons stationed nearby presented memorial

wreaths, one of which was inscribed with the words, “To Our Gallant and Worthy Foe.” It was an extremely respectful way to care for the body of the enemy, and for that, I have much respect for the Number 3 Squadron. Even though this man was the enemy, they knew he was just doing his job, as they would do theirs. It wasn’t personal, it was just war. In 1975 the body was moved to a Richthofen family grave plot at the Südfriedhof in Wiesbaden.

wreaths, one of which was inscribed with the words, “To Our Gallant and Worthy Foe.” It was an extremely respectful way to care for the body of the enemy, and for that, I have much respect for the Number 3 Squadron. Even though this man was the enemy, they knew he was just doing his job, as they would do theirs. It wasn’t personal, it was just war. In 1975 the body was moved to a Richthofen family grave plot at the Südfriedhof in Wiesbaden.

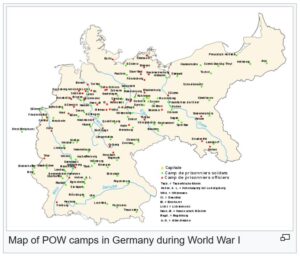

World War I was a different era, even in the way war was conducted. Oh, war is still war, and there is wounding, bombing, killing, and capturing. Nevertheless, with one leader, Kaiser Wilhelm II, there was also compassion. After being captured and placed in a POW camp, a British officer, Captain Robert Campbell found out that his mother was dying. He couldn’t bear the thought of not seeing his mother before she passed away, and in his grief, he took a chance. He appealed to Kaiser Wilhelm II, asking to be allowed to go home to visit his mother before she died. Amazingly, Kaiser Wilhelm II granted his request, on the condition that he return to the POW camp after the visit.

World War I was a different era, even in the way war was conducted. Oh, war is still war, and there is wounding, bombing, killing, and capturing. Nevertheless, with one leader, Kaiser Wilhelm II, there was also compassion. After being captured and placed in a POW camp, a British officer, Captain Robert Campbell found out that his mother was dying. He couldn’t bear the thought of not seeing his mother before she passed away, and in his grief, he took a chance. He appealed to Kaiser Wilhelm II, asking to be allowed to go home to visit his mother before she died. Amazingly, Kaiser Wilhelm II granted his request, on the condition that he return to the POW camp after the visit.

When you think about it, once he was safely home with his mother, Captain Campbell could have simply stayed. Seriously, what could the Kaiser have done about it. Nevertheless, being an honorable man, Captain Campbell kept his promise to Kaiser Wilhelm II and returned from Kent to Germany after visiting his mother for a week. He stayed at the camp until the war ended in 1918. That was not the end of the story, however.

On August 24, 1914, then 29-year-old Captain Campbell, of the 1st Battalion East Surrey Regiment, was captured in northern France. He was sent to a prisoner-of-war (POW) camp in Magdeburg, north-east Germany. It was there that he received the heartbreaking news that his mother, Louise was dying of cancer. Captain Campbell traveled through the Netherlands and then by boat and train to Gravesend in Kent, where he spent a week with his mother before returning to Germany the same way. His mother died in February 1917.

With the kindness of the Kaiser, and a duty to honor his word, Captain Campbell, knowing that if he didn’t return, no one else would ever be given that same consideration, Captain Campbell returned to Germany. Strangely, there was no issues during his return. I suppose the Kaiser could have cleared the way previously, but it would be my guess that the Kaiser was just as shocked by the return as I am. Unfortunately, Britain wasn’t as considerate, because they blocked a similar request from German prisoner Peter Gastreich, who was being held at an internment camp on the Isle of Man. After that no other British prisoners of war were afforded compassionate leave.

As for Captain Campbell, while he felt duty-bound to return to captivity, he did not feel duty-bound to stay in

captivity. As soon as Captain Campbell returned to the camp, he set about trying to escape. He and a group of other prisoners spent nine months digging their way out of the camp before being captured on the Dutch border and sent back. He remained in the camp until 1918 and served in the military until 1925. Captain Campbell rejoined the military when World War II broke out in 1939 and served as the chief observer of the Royal Observer Corps on the Isle of Wight. He died in the Isle of Wight in July 1966, aged 81.

captivity. As soon as Captain Campbell returned to the camp, he set about trying to escape. He and a group of other prisoners spent nine months digging their way out of the camp before being captured on the Dutch border and sent back. He remained in the camp until 1918 and served in the military until 1925. Captain Campbell rejoined the military when World War II broke out in 1939 and served as the chief observer of the Royal Observer Corps on the Isle of Wight. He died in the Isle of Wight in July 1966, aged 81.

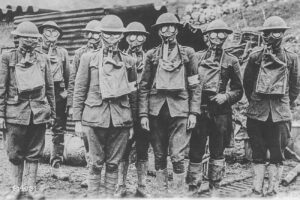

The initials “G.I.” bring a picture of a US soldier for most people They aren’t viewed as glamorous, and usually look like they have just crawled out of the trenches somewhere, but never is there a shred of doubt as to their toughness. The name, American G.I. is synonymous with “American infantryman.” Really, everything American Military was tagged G.I. When soldiers returned from World War II and now other wars or even non-wartime military service are eligible for the benefits of the “G.I.” Bill, including education. In fact, it was often the G.I. Bill that drew young recruits into the service in the first place. Let’s face it, college is expensive, and three years of service seems a small price to pay.

The initials “G.I.” bring a picture of a US soldier for most people They aren’t viewed as glamorous, and usually look like they have just crawled out of the trenches somewhere, but never is there a shred of doubt as to their toughness. The name, American G.I. is synonymous with “American infantryman.” Really, everything American Military was tagged G.I. When soldiers returned from World War II and now other wars or even non-wartime military service are eligible for the benefits of the “G.I.” Bill, including education. In fact, it was often the G.I. Bill that drew young recruits into the service in the first place. Let’s face it, college is expensive, and three years of service seems a small price to pay.

The American soldier was, and for patriots of our day is one of the most loved and respected groups of people  in the United States. They even inspired one of most popular toys in the 1960s and 1980s. the G.I. Joe doll, and later, G.I. Jane, inspired by Demi Moore in her movie with the same name. The dolls and the movie brought the G.I. Joe and Jane dolls to a whole new generation of kids.

in the United States. They even inspired one of most popular toys in the 1960s and 1980s. the G.I. Joe doll, and later, G.I. Jane, inspired by Demi Moore in her movie with the same name. The dolls and the movie brought the G.I. Joe and Jane dolls to a whole new generation of kids.

We all know about the G.I. dolls and soldiers, but do we know what G.I. means? Most of us truly don’t. Many people probably assumed it was something along the lines of “Government Infantry,” “General Infantry,” or perhaps a “Government Issue” label stamped on military rations and equipment. Those are good guesses, but they are also wrong. In fact, “G.I.” stands for “Galvanized Iron.” While that sounds like a tough thing, and  maybe that is to say that the soldiers were tough, the reality is that the name comes from something entirely different…and totally not exciting, tough, or even cool. In the early 20th century, believe it or not…military trash cans and buckets were stamped with the initials G.I. It wasn’t because they belonged to the military. but simply because galvanized iron was the material from which the cans and buckets were made. So, during World War I, the initials became a proxy for all things to do with infantry, and the usage stuck. So, I guess we can banish the initials, accept it as all things military, or maybe embrace the term as being the toughest of the tough and the strongest of the strong. I think I like the last one the best.

maybe that is to say that the soldiers were tough, the reality is that the name comes from something entirely different…and totally not exciting, tough, or even cool. In the early 20th century, believe it or not…military trash cans and buckets were stamped with the initials G.I. It wasn’t because they belonged to the military. but simply because galvanized iron was the material from which the cans and buckets were made. So, during World War I, the initials became a proxy for all things to do with infantry, and the usage stuck. So, I guess we can banish the initials, accept it as all things military, or maybe embrace the term as being the toughest of the tough and the strongest of the strong. I think I like the last one the best.

In any war, there must be a nation’s first casualty. World War I could be no different. On March 28, 1915, the first American citizen was killed in the eighth month of World War I. The United States didn’t even enter the war until April 6, 1917. Nevertheless, Leon Thrasher, who was a 31-year-old mining engineer and a native of Massachusetts, drowned when a German U-Boat, the U-28 torpedoed a cargo-passenger ship the British RMS Falaba, a West African steamship, on which Thrasher was a passenger. The sinking became known as “The Thrasher Incident.” The RMS Falaba was on its way from Liverpool to West Africa, off the coast of England. Of the 242 passengers and crew on board RMS Falaba, 104 drowned. Thrasher was employed on the Gold Coast in British West Africa, and on March 28, 1915, he was on the RMS Falaba, as a passenger, returning to his post, following a trip to England.

In any war, there must be a nation’s first casualty. World War I could be no different. On March 28, 1915, the first American citizen was killed in the eighth month of World War I. The United States didn’t even enter the war until April 6, 1917. Nevertheless, Leon Thrasher, who was a 31-year-old mining engineer and a native of Massachusetts, drowned when a German U-Boat, the U-28 torpedoed a cargo-passenger ship the British RMS Falaba, a West African steamship, on which Thrasher was a passenger. The sinking became known as “The Thrasher Incident.” The RMS Falaba was on its way from Liverpool to West Africa, off the coast of England. Of the 242 passengers and crew on board RMS Falaba, 104 drowned. Thrasher was employed on the Gold Coast in British West Africa, and on March 28, 1915, he was on the RMS Falaba, as a passenger, returning to his post, following a trip to England.

The sinking, brought with it a claim from the Germans that the submarine’s crew had  followed all protocol when approaching RMS Falaba. The Germans said that they gave the passengers ample time to abandon ship, and that they fired only when British torpedo destroyers began to approach to give aid to the Falaba. Of course, the British official press report of the incident disagreed, claiming that the Germans had acted improperly, “It is not true that sufficient time was given the passengers and the crew of this vessel to escape. The German submarine closed in on the Falaba, ascertained her name, signaled her to stop, and gave

followed all protocol when approaching RMS Falaba. The Germans said that they gave the passengers ample time to abandon ship, and that they fired only when British torpedo destroyers began to approach to give aid to the Falaba. Of course, the British official press report of the incident disagreed, claiming that the Germans had acted improperly, “It is not true that sufficient time was given the passengers and the crew of this vessel to escape. The German submarine closed in on the Falaba, ascertained her name, signaled her to stop, and gave  those on board five minutes to take to the boats. It would have been nothing short of a miracle if all the passengers and crew of a big liner had been able to take to their boats within the time allotted.”

those on board five minutes to take to the boats. It would have been nothing short of a miracle if all the passengers and crew of a big liner had been able to take to their boats within the time allotted.”

The sinking of RMS Falaba, and Thrasher’s subsequent death, was mentioned again in a memorandum sent by the US government, which was drafted by President Woodrow Wilson himself and addressed to the German government after the German submarine attack on the British passenger ship Lusitania on May 7, 1915, in which 1,201 people were drowned, including 128 Americans. President Wilson’s note was clearly a warning, calling for the US and Germany to come to a full and complete understanding as to the grave situation which had resulted from the German policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. In response to the warning, Germany abandoned the policy shortly thereafter. However, the policy abandonment was reversed in early 1917, and that was the final straw that put the United States into World War I on April 6, 1917.

In the toughest of times, the women of the west had to participate in the work force since families had to make ends meet any way they could. But the work was demanding, often outdoors and with physical labor and lots of hours doing agricultural and other large-scale jobs. By the end of the day, they were exhausted…just like their men. It’s not that women aren’t capable of hard work, because they absolutely are. Nevertheless, their bodies aren’t built for the same kind of work as the men…or at least it isn’t as easy as for the men.

In the toughest of times, the women of the west had to participate in the work force since families had to make ends meet any way they could. But the work was demanding, often outdoors and with physical labor and lots of hours doing agricultural and other large-scale jobs. By the end of the day, they were exhausted…just like their men. It’s not that women aren’t capable of hard work, because they absolutely are. Nevertheless, their bodies aren’t built for the same kind of work as the men…or at least it isn’t as easy as for the men.

During World War I and World War II, when so many men were called to duty, and so many were killed, the workforce at home was dramatically shrinking. So, like they always did, the women stepped up. It’s not that the men weren’t stepping up too,  because going to war is most certainly stepping up. Really, everyone was doing a job that was not in their normal wheelhouse. Times were tough and tough times called for tough people. It the war was going to be won, the military had to be supplied with the necessary materials to fight with. Things like ammunition, uniforms, boots, tanks, planes, bombs, guns, and much more were vital; and without the help of the women back home, the men would not have the things they needed to win the war.

because going to war is most certainly stepping up. Really, everyone was doing a job that was not in their normal wheelhouse. Times were tough and tough times called for tough people. It the war was going to be won, the military had to be supplied with the necessary materials to fight with. Things like ammunition, uniforms, boots, tanks, planes, bombs, guns, and much more were vital; and without the help of the women back home, the men would not have the things they needed to win the war.

The thing about these particular women was that at that time in history, most women were stay-at-home moms, and at that time that really meant cleaning the house, cooking, and caring for the children. These were not times of going to the gym to work out, and the main exercise was the daily chores. Don’t get me wrong, because the chores  were hard work, and that did keep the women in shape, but they weren’t miners or factory workers. This necessary work was all new to them. The endeavor to bring these women into the workforce was no small undertaking. The had to be trained and trained quickly. There was no time to waste. The women, for their part, jumped at the chance to help their men and the men of the nation. They learned their new jobs quickly and did their jobs efficiently. They were loyal to their men and their country, and they were willing to take on the exhausting jobs they were asked to take on. In fact, I don’t think the wars could have been won, without both parts…the men and the women, and the necessary work they did.

were hard work, and that did keep the women in shape, but they weren’t miners or factory workers. This necessary work was all new to them. The endeavor to bring these women into the workforce was no small undertaking. The had to be trained and trained quickly. There was no time to waste. The women, for their part, jumped at the chance to help their men and the men of the nation. They learned their new jobs quickly and did their jobs efficiently. They were loyal to their men and their country, and they were willing to take on the exhausting jobs they were asked to take on. In fact, I don’t think the wars could have been won, without both parts…the men and the women, and the necessary work they did.

Trench warfare is a type of land warfare using occupied lines largely comprising military trenches, in which troops are well-protected from the enemy’s small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from artillery. That doesn’t protect them from many other weapons, like tanks, bomber planes, and some things that seem far more benign…rats and disease, not that these things aren’t dangerous. In fact, during World War I, these seemingly benign pests were becoming a deadly problem. Trench foot was one of the biggest disease problems, due to the wet and dirty conditions the men basically lived in.

Trench warfare is a type of land warfare using occupied lines largely comprising military trenches, in which troops are well-protected from the enemy’s small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from artillery. That doesn’t protect them from many other weapons, like tanks, bomber planes, and some things that seem far more benign…rats and disease, not that these things aren’t dangerous. In fact, during World War I, these seemingly benign pests were becoming a deadly problem. Trench foot was one of the biggest disease problems, due to the wet and dirty conditions the men basically lived in.

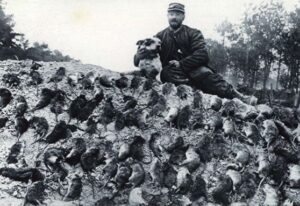

The rats…well, they were a bigger problem. The fact that the men “lived” in the trenches meant things like human waste, food scraps, and dead bodies drew the rats, and rats spread disease like typhus and the plague,  which made the problem of disease more deadly. Since trash disposal wasn’t easy in the trenches, the men often threw empty food tins out of the trenches at night. Then, the rats could be heard turning the tins over and licking the last tidbits out of them. For me the whole scene would be enough to make me want to run screaming from the scene, but that could get a soldier killed. Something had to be done…and done quickly. Due to the plentiful amount of food, some of these rats grew quite large in size. One story tells of a soldier who spotted one the size of a cat.

which made the problem of disease more deadly. Since trash disposal wasn’t easy in the trenches, the men often threw empty food tins out of the trenches at night. Then, the rats could be heard turning the tins over and licking the last tidbits out of them. For me the whole scene would be enough to make me want to run screaming from the scene, but that could get a soldier killed. Something had to be done…and done quickly. Due to the plentiful amount of food, some of these rats grew quite large in size. One story tells of a soldier who spotted one the size of a cat.

Something had to be done, so French troops tried to control the rat problem by bringing terrier dogs into the trenches with them. The plan was to let the dogs catch and kill rats, and it quickly became an interesting way to pass the time during daylight hours. Because of the dangers presented by the rats, the military actually offered soldiers a reward for killing the rats as incentive to decrease their numbers. It was a great idea, but not really practical, because rats are notoriously great escape artists…at least from humans. Nevertheless, apparently the troops got so into the

game, with one army corps managed to catch 8,000 in a single night. Other soldiers adopted cats instead of dogs, and it’s believed around 500,000 cats helped out in the trenches over the course of World War I. Many of the cats, and some of the dogs, ended up serving as mascots for troops on the front lines as well as hunters. I guess the plan worked, but maybe the animals should have been given a medal too.

game, with one army corps managed to catch 8,000 in a single night. Other soldiers adopted cats instead of dogs, and it’s believed around 500,000 cats helped out in the trenches over the course of World War I. Many of the cats, and some of the dogs, ended up serving as mascots for troops on the front lines as well as hunters. I guess the plan worked, but maybe the animals should have been given a medal too.

When I think of war and of the largest offensive in United States history, I don’t picture a battle in World War I. Nevertheless, I should. The Meuse–Argonne offensive, which was also called the Meuse River–Argonne Forest offensive, the Battles of the Meuse–Argonne, and the Meuse–Argonne campaign, depending on who you were, was a major part of the final Allied offensive of World War I that stretched along the entire Western Front. The offensive ran for a total of 47 days, from September 26, 1918, until the Armistice of November 11, 1918, and it was the largest in United States military history, past or present.

When I think of war and of the largest offensive in United States history, I don’t picture a battle in World War I. Nevertheless, I should. The Meuse–Argonne offensive, which was also called the Meuse River–Argonne Forest offensive, the Battles of the Meuse–Argonne, and the Meuse–Argonne campaign, depending on who you were, was a major part of the final Allied offensive of World War I that stretched along the entire Western Front. The offensive ran for a total of 47 days, from September 26, 1918, until the Armistice of November 11, 1918, and it was the largest in United States military history, past or present.

The offensive involved 1.2 million American soldiers, and as battles go, it is the second deadliest in American history. During the course of the battle, there were over 350,000 casualties including 28,000 German lives, 26,277 American lives, and an unknown number of French lives. The losses involving the United States were compounded by the inexperience of many of the troops, the tactics used during the early phases of the operation, and in no small way…the widespread onset of the global influenza outbreak called the “Spanish flu.” The 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic, also known as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly

global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The pandemic affected an estimated 500 million people, or approximately a third of the global population. It is estimated that 17 to 50 million, and possibly as high as 100 million people lost their lives, which probably increased the deaths during the Meuse-Argonne offensive.

global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The pandemic affected an estimated 500 million people, or approximately a third of the global population. It is estimated that 17 to 50 million, and possibly as high as 100 million people lost their lives, which probably increased the deaths during the Meuse-Argonne offensive.

The Meuse–Argonne was the principal engagement of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) during World War I, and it was what finally brought the war to an end. It was the largest and bloodiest operation of World War I for the AEF. Nevertheless, by October 31, the Americans had advanced 9.3 miles and had cleared the Argonne Forest. The French advanced 19 miles to the left of the Americans, reaching the Aisne River. The American forces split into two armies at this point. General Liggett led the First Army and advanced to the Carignan-Sedan-Mezieres Railroad. Lieutenant General Robert L Bullard led the Second Army and was directed to move eastward toward Metz. The two United States armies faced portions of 31 German divisions during this phase. The American troops captured German defenses at Buzancy, allowing French troops to cross the Aisne River. There, they rushed forward, capturing Le Chesne, also known as the Battle of Chesne (French: Bataille du Chesne).

In the final days, the French forces conquered the immediate objective, Sedan and its critical railroad hub in a

battle known as the Advance to the Meuse (French: Poussée vers la Meuse), and on November 6, American forces captured surrounding hills. On November 11, news of the German armistice put a sudden end to the fighting. That was fortunate for the armies, but for my 1st cousin twice removed, William Henry Davis, it was six days too late. He lost his life on November 5, 1918, on the west bank of the Meuse during these battles. He was just 30 years old at the time.

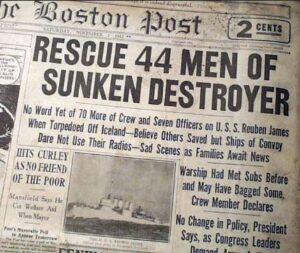

It is common practice in the military to name destroyers (DD) and destroyer Escorts (DE) after Navy and Marine Corps heroes. The USS Reuben James (DD-245) was a four-funnel (four stack) Clemson-class destroyer made after World War I, and it was the first of three US Navy ships named for Boatswain’s Mate Reuben James (1776–1838), who distinguished himself fighting in the First Barbary War. Apparently, on August 3, 1804, James put himself between his commanding officer, Lieutenant Stephen Decatur and the sword of a Tripolitan sailor, who was trying to defend his commander. When James stepped between the descending sword and his commander, he took the blow to his head. Amazingly, the blow did not kill him, and he recovered later to continue serving in the Navy.

It is common practice in the military to name destroyers (DD) and destroyer Escorts (DE) after Navy and Marine Corps heroes. The USS Reuben James (DD-245) was a four-funnel (four stack) Clemson-class destroyer made after World War I, and it was the first of three US Navy ships named for Boatswain’s Mate Reuben James (1776–1838), who distinguished himself fighting in the First Barbary War. Apparently, on August 3, 1804, James put himself between his commanding officer, Lieutenant Stephen Decatur and the sword of a Tripolitan sailor, who was trying to defend his commander. When James stepped between the descending sword and his commander, he took the blow to his head. Amazingly, the blow did not kill him, and he recovered later to continue serving in the Navy.

The Destroyer named after Boatswain’s Mate Reuben James, was the first sunk by hostile action in the European Theater of World War II. The USS Reuben James was laid down on April 2, 1919, by the New York Shipbuilding Corporation of Camden, New Jersey, launched on October 4, 1919, and commissioned on September 24, 1920. the ship was assigned to the Atlantic Fleet. Mainly, it was being used in the Mediterranean Sea during 1921–1922. The ship went from Newport, Rhode Island, on November 30, 1920, to Zelenika, Yugoslavia and arrived on December 18th. It operated in the Adriatic Sea and the Mediterranean out of Zelenika and Gruz (Dubrovnik), Yugoslavia, assisting refugees and participating in post-World War I investigations during the spring and summer of 1921. Then, it joined the protected cruiser Olympia at ceremonies marking the return of the Unknown Soldier to the United States in October 1921 at Le Havre. From October 29, 1921, to February 3, 1922, it assisted the American Relief Administration in its efforts to relieve hunger and misery at Danzig. After completing its tour of duty in the Mediterranean, it departed Gibraltar on July 17th.

Following its tour in the Mediterranean, the ship was based out of New York City, where it routinely patrolled the Nicaraguan coast to prevent the delivery of weapons to revolutionaries in early 1926. During the spring of 1929, it participated in fleet maneuvers that helped develop naval airpower. On January 20, 1931, the Reuben James was

decommissioned at Philadelphia, only to be recommissioned on March 9, 1932. The ship again operated in the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, patrolling Cuban waters during the coup by Fulgencio Batista. Then, in 1934, it was transferred to San Diego. After maneuvers that evaluated aircraft carriers, the Reuben James returned to the Atlantic Fleet in January 1939.

Upon the beginning of World War II in Europe in September 1939, but before the United States joined in the fight, the Reuben James was assigned to the Neutrality Patrol, guarding the Atlantic and Caribbean approaches to the American coast. The ship joined the force established to escort convoys sailing to Great Britain in March 1941. With U-Boat attacks on the rise, this force began escorting convoys as far as Iceland, after which the convoys became the responsibility of British escorts. At that time, it was based at Hvalfjordur, Iceland, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Heywood Lane Edwards.

It would be the escort post that would be the ship in the wrong place at the wrong time. On October 23rd, it sailed from Naval Station Argentia, Newfoundland, with four other destroyers, escorting eastbound Convoy HX 156. All seemed to be going well until, at dawn on October 31st, the Reuben James was torpedoed near Iceland by German U-Boat U-552 commanded by Kapitänleutnant Erich Topp. The Reuben James had positioned itself between an ammunition ship in the convoy and the known position of a German “wolfpack.” The “wolfpack” was a group of submarines poised to attack the convoy. Apparently, the destroyer was not flying the Ensign of the United States, that might have saved it…or maybe not, since it was in the process of dropping depth charges on another U-boat when U-552 engaged. The Reuben James was hit forward by a torpedo meant for a merchant ship and the torpedo blew the entire bow off when a magazine exploded upon the torpedoes impact. The bow of the Reuban James sank immediately. The aft section floated for five minutes before going down. I can only

imagine the shock of those around them when the ship was gone so quickly. USS Reuben James carried a crew of seven officers and 136 enlisted men. They also had one enlisted passenger. Of the total of 144 men on board, 100 were killed, including all the officers. Only 44 enlisted men survived the attack. It was the first US warship sunk in World War II, and strangely, the destroyer was sunk before the United States had officially joined the war.

imagine the shock of those around them when the ship was gone so quickly. USS Reuben James carried a crew of seven officers and 136 enlisted men. They also had one enlisted passenger. Of the total of 144 men on board, 100 were killed, including all the officers. Only 44 enlisted men survived the attack. It was the first US warship sunk in World War II, and strangely, the destroyer was sunk before the United States had officially joined the war.

As World War I…the “War to end all Wars,” was coming to a close, there still remained one serious German stronghold that had to be taken down in order to ensure Allied success in winning the war. That stronghold, known to the Allies as the Hindenburg Line, an area they named after the German commander in chief, Paul von Hindenburg, was built in late 1916. The Germans called it the Siegfried Line. Either was, the Hindenburg Line was a heavily fortified zone running several miles behind the active front between the north coast of France and Verdun, near the border of France and Belgium. This area was a must win, must take back line, if the Allies were going to win the war.

As World War I…the “War to end all Wars,” was coming to a close, there still remained one serious German stronghold that had to be taken down in order to ensure Allied success in winning the war. That stronghold, known to the Allies as the Hindenburg Line, an area they named after the German commander in chief, Paul von Hindenburg, was built in late 1916. The Germans called it the Siegfried Line. Either was, the Hindenburg Line was a heavily fortified zone running several miles behind the active front between the north coast of France and Verdun, near the border of France and Belgium. This area was a must win, must take back line, if the Allies were going to win the war.

The German army was working hard to make it very difficult to break through the Hindenburg line by September 1918. At that time, the German line consisted of six defensive lines. The zone formed by these six lines measured some 6,000 yards deep, and it was ribbed with lengths of barbed wire and dotted with concrete emplacements to be used as firing positions. It was a fortress that the Germans were sure would be impenetrable. However, while the Hindenburg Line was heavily fortified, it was not without weakness. Its southern part was most vulnerable to attack, because it included the Saint Quentin Canal, and the entire area was not totally out of sight of artillery observation by the enemy. Any attack by the Allies would need to come through this weakness. Another weakness was that the whole system was laid out linearly, as opposed to newer constructions that had adapted to more recent developments in firepower and were built with scattered “strong points” laid out like a checkerboard to enhance the intensity of artillery fire. These things would be the saving grace for the Allies, and the downfall for the Germans.

Knowing these vulnerabilities, the Allies began to concentrate all the force built up during their so-called “Hundred Days Offensive,” to their advantage. The operation kicked off on August 8, 1918, and by late September, the Allies had gained a decisive victory at Amiens, France, against the Hindenburg Line. Australian, British, French, and American forces participated in the attack on the Hindenburg Line. The attack began with a huge bombardment, using 1,637 guns along a 10,000-yard-long front. The final 24 hours of the offensive saw the British firing a record 945,052 shells. After capturing the Saint Quentin Canal with a creeping barrage of fire…126 shells for each 500 yards of German trench over an eight-hour period, the Allies successfully breached the Hindenburg Line on September 29, 1918.

The attack was pushed forward by Australian and United States troops, who, out of a must-win sense of urgency, attacked the heavily fortified town of Bellicourt with tanks and aircraft. The battle raged on for four days, with heavy losses on both sides. Finally, the Germans were forced to retreat. With Kaiser Wilhelm II

pressured by the military into accepting governmental reform and Germany’s ally, Bulgaria, suing for an armistice by the end of September, the Central Powers were in disarray on the battlefield, as well as the home front. The Allies continued to press their advantage on the Western Front throughout the month of October, and against their predictions, World War I came to an almost abrupt end on November 11, 1918.

pressured by the military into accepting governmental reform and Germany’s ally, Bulgaria, suing for an armistice by the end of September, the Central Powers were in disarray on the battlefield, as well as the home front. The Allies continued to press their advantage on the Western Front throughout the month of October, and against their predictions, World War I came to an almost abrupt end on November 11, 1918.