women

When nations go to war, it is not just the soldiers fighting, who pay the price. War is expensive, and everyone has to help with the war effort. The American people are famous for pitching in when “push comes to shove” and World War II would be no different. On May 15, 1942, the American war effort needed the American citizens to “tighten their belts” so that the funds could be used to help our soldiers. So, gasoline rationing began in 17 Eastern states. It was the first attempt to help the American war effort during World War II. President Franklin D Roosevelt then ensured that by the end of the year, mandatory gasoline rationing was in effect in all 48 states. Things got tougher, and the people felt the pinch, but they were willing to do what was necessary to win the war.

When nations go to war, it is not just the soldiers fighting, who pay the price. War is expensive, and everyone has to help with the war effort. The American people are famous for pitching in when “push comes to shove” and World War II would be no different. On May 15, 1942, the American war effort needed the American citizens to “tighten their belts” so that the funds could be used to help our soldiers. So, gasoline rationing began in 17 Eastern states. It was the first attempt to help the American war effort during World War II. President Franklin D Roosevelt then ensured that by the end of the year, mandatory gasoline rationing was in effect in all 48 states. Things got tougher, and the people felt the pinch, but they were willing to do what was necessary to win the war.

After World War I, many Americans were less than enthusiastic about entering another world war, at least until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The day after the attack, Congress almost unanimously approved Roosevelt’s request for a declaration of war against Japan and three days later Japan’s allies Germany and Italy declared war against the United States. Like it or not, war was on. With the onset of  war, Americans almost immediately felt the impact of the war. The economy quickly shifted from a focus on consumer goods into full-time war production. Everyone was pitching in, and everyone was willing. With so many men in now in the fighting, the women went to work in the factories to replace the now enlisted men, automobile factories began producing tanks and planes for Allied forces and households were required to limit their consumption of such products as rubber, gasoline, sugar, alcohol, and cigarettes. Anything that might be needed for the war effort, was sacrificed by the American people, who felt like it was them just doing their part…for the most part.

war, Americans almost immediately felt the impact of the war. The economy quickly shifted from a focus on consumer goods into full-time war production. Everyone was pitching in, and everyone was willing. With so many men in now in the fighting, the women went to work in the factories to replace the now enlisted men, automobile factories began producing tanks and planes for Allied forces and households were required to limit their consumption of such products as rubber, gasoline, sugar, alcohol, and cigarettes. Anything that might be needed for the war effort, was sacrificed by the American people, who felt like it was them just doing their part…for the most part.

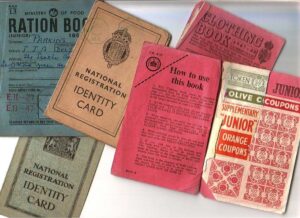

A number of commodities were rationed. Rubber was the first to go, after the Japanese invasion of the Dutch East Indies cut off the US supply. The shortage of rubber, of course affected the availability of products such as tires and anything else that used rubber. Gasoline was a given, because it would be needed to move the troops. Also, it was thought that less gasoline, would bring less travel and therefore less wear and tear on rubber tires. At first, the government urged voluntary gasoline rationing, but by the spring of 1942 it was obvious that people wouldn’t assume that their use was extravagant and not a frivolous use. Hense, first 17 states put mandatory gasoline rationing into effect, and by December, controls were extended across the entire country.

The Government issued ration stamps for gasoline were issued by local boards and pasted to the windshield of  a family or individual’s automobile. The type of stamp determined the gasoline allotment for that automobile. Black stamps signified non-essential travel and so allowed no more than three gallons per week. Red stamps were for workers who needed more gas, including policemen and mail carriers. With the restrictions, gasoline became a hot commodity on the black market, while legal measures of conserving gas, like carpooling, became the norm. Another Government mandated method to reduce gas consumption, the government passed a mandatory wartime speed limit of 35 mph, known as the “Victory Speed.” Things got tight in many areas, but the American people ultimately persevered, and the war effort supplied the needed commodities.

a family or individual’s automobile. The type of stamp determined the gasoline allotment for that automobile. Black stamps signified non-essential travel and so allowed no more than three gallons per week. Red stamps were for workers who needed more gas, including policemen and mail carriers. With the restrictions, gasoline became a hot commodity on the black market, while legal measures of conserving gas, like carpooling, became the norm. Another Government mandated method to reduce gas consumption, the government passed a mandatory wartime speed limit of 35 mph, known as the “Victory Speed.” Things got tight in many areas, but the American people ultimately persevered, and the war effort supplied the needed commodities.

In the toughest of times, the women of the west had to participate in the work force since families had to make ends meet any way they could. But the work was demanding, often outdoors and with physical labor and lots of hours doing agricultural and other large-scale jobs. By the end of the day, they were exhausted…just like their men. It’s not that women aren’t capable of hard work, because they absolutely are. Nevertheless, their bodies aren’t built for the same kind of work as the men…or at least it isn’t as easy as for the men.

In the toughest of times, the women of the west had to participate in the work force since families had to make ends meet any way they could. But the work was demanding, often outdoors and with physical labor and lots of hours doing agricultural and other large-scale jobs. By the end of the day, they were exhausted…just like their men. It’s not that women aren’t capable of hard work, because they absolutely are. Nevertheless, their bodies aren’t built for the same kind of work as the men…or at least it isn’t as easy as for the men.

During World War I and World War II, when so many men were called to duty, and so many were killed, the workforce at home was dramatically shrinking. So, like they always did, the women stepped up. It’s not that the men weren’t stepping up too,  because going to war is most certainly stepping up. Really, everyone was doing a job that was not in their normal wheelhouse. Times were tough and tough times called for tough people. It the war was going to be won, the military had to be supplied with the necessary materials to fight with. Things like ammunition, uniforms, boots, tanks, planes, bombs, guns, and much more were vital; and without the help of the women back home, the men would not have the things they needed to win the war.

because going to war is most certainly stepping up. Really, everyone was doing a job that was not in their normal wheelhouse. Times were tough and tough times called for tough people. It the war was going to be won, the military had to be supplied with the necessary materials to fight with. Things like ammunition, uniforms, boots, tanks, planes, bombs, guns, and much more were vital; and without the help of the women back home, the men would not have the things they needed to win the war.

The thing about these particular women was that at that time in history, most women were stay-at-home moms, and at that time that really meant cleaning the house, cooking, and caring for the children. These were not times of going to the gym to work out, and the main exercise was the daily chores. Don’t get me wrong, because the chores  were hard work, and that did keep the women in shape, but they weren’t miners or factory workers. This necessary work was all new to them. The endeavor to bring these women into the workforce was no small undertaking. The had to be trained and trained quickly. There was no time to waste. The women, for their part, jumped at the chance to help their men and the men of the nation. They learned their new jobs quickly and did their jobs efficiently. They were loyal to their men and their country, and they were willing to take on the exhausting jobs they were asked to take on. In fact, I don’t think the wars could have been won, without both parts…the men and the women, and the necessary work they did.

were hard work, and that did keep the women in shape, but they weren’t miners or factory workers. This necessary work was all new to them. The endeavor to bring these women into the workforce was no small undertaking. The had to be trained and trained quickly. There was no time to waste. The women, for their part, jumped at the chance to help their men and the men of the nation. They learned their new jobs quickly and did their jobs efficiently. They were loyal to their men and their country, and they were willing to take on the exhausting jobs they were asked to take on. In fact, I don’t think the wars could have been won, without both parts…the men and the women, and the necessary work they did.

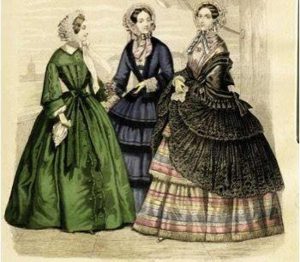

Women have always had an eye for fashion, but I can’t say that having an “eye” for fashion, is the same as having common sense for fashion. In the Victorian era, Bottle-green dresses were all the rage. I understand the love of the color green, and how a beautiful emerald green might be a coveted color. The problem occurs with the process of obtaining that color. The process used to achieve this lovely shade of green involved the fabric being dyed using large amounts of arsenic…yes, rat poison!! Some women suffered nausea, impaired vision, and skin reactions to the dye. They endured the suffering because the dresses were only worn on special occasions, thereby limiting exposure to the arsenic in the fabric. By contrast, it was the garment makers were the real sufferers. Many of them became very ill and even died to bring this trend to the fashionable set.

Women have always had an eye for fashion, but I can’t say that having an “eye” for fashion, is the same as having common sense for fashion. In the Victorian era, Bottle-green dresses were all the rage. I understand the love of the color green, and how a beautiful emerald green might be a coveted color. The problem occurs with the process of obtaining that color. The process used to achieve this lovely shade of green involved the fabric being dyed using large amounts of arsenic…yes, rat poison!! Some women suffered nausea, impaired vision, and skin reactions to the dye. They endured the suffering because the dresses were only worn on special occasions, thereby limiting exposure to the arsenic in the fabric. By contrast, it was the garment makers were the real sufferers. Many of them became very ill and even died to bring this trend to the fashionable set.

Another crazy style was known as Panniers, which comes from the French word “panier,” meaning “basket.” These were popular in the 17th and 18th centuries. The look involved a boxed petticoat to expanded the width of skirts and dresses. The contraption stood out on either side of the waistline…straight out!! Panniers varied in size and were made of whalebone, wood, metal, and sometimes reeds. Extremely large panniers were worn mostly on special occasions and reflected the wearer’s social status. Even the servants wore them, though in a much smaller version. Two women couldn’t walk through an entrance at the same time or sit on a couch together, because their panniers took up an entire extra seat or more. The device was also uncomfortable, limiting movement and activity.

In the 1910s, French designer Paul Poiret, who was well known as “The King of Fashion” in America, debuted the hobble skirt. The long, close-fitting skirts forced women who wore them to adopt mincing, tiny steps. True, Poiret’s design liberated women from heavy petticoats and constricting corsets. But as he said, “Yes, I freed the

bust. But I shackled the legs.” This makes me wonder why women allow their fashion ideas to come from men…who don’t have to wear the clothes they design. Some of these “fashions” were enough to make a woman faint, because her corset was too tight, and she could not get sufficient air.

bust. But I shackled the legs.” This makes me wonder why women allow their fashion ideas to come from men…who don’t have to wear the clothes they design. Some of these “fashions” were enough to make a woman faint, because her corset was too tight, and she could not get sufficient air.

During the Roaring ’20s, women no longer wanted the hourglass shape. Now the style was the boyish flapper figure. Underwear had to change to assist in this new look, and women who were “busty,” had a big problem and the underwear needed a big overhaul. The goal of every undergarment was to flatten the breasts and torso, so that flapper dresses could hang straight down without any curvaceous interruptions. Corset-makers R. and W.H. Symington invented a garment, the Symington Side Lacer, that would flatten the breasts. The wearer would slip the garment over her head and pull the straps and side laces tight to smooth out curves. Other manufacturers designed similar devices. The Miracle Reducing Rubber Brassiere was “scientifically designed without bones or lacings,” while the Bramley Corsele combined the brassiere and corset into one piece that easily layered under dresses. I wonder how anyone could breathe in these prisons known as underwear.

The Crinoline, also known as the hoop skirt, was a bell-shaped device that pushed the volume of skirts to an extreme degree. Worn in the 1800s by Victorian women, Crinolines were originally petticoats made of linen stiffened with horsehair. Wonderful…now we are wearing horsehair under our skirts. This created a big problem. It was just too hot with so many petticoats. Later, the invention of the steel cage crinoline offered the same voluminous look without the extra heat and bulk of thick petticoats. These undergarments were clumsy and hard to control, but they were also dangerous. In 1858, a young woman in Boston died when her large skirt caught embers from a fireplace in her parlor and went up in flames. It all happened to fast to save her. Nineteen such deaths occurred in a two-month period. That is a heavy price to pay in the name of fashion.

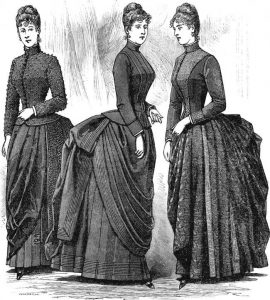

And then, there was the “Grecian bend,” the Victorian bustle. It arrived on the scene in the 1870s. The earliest version of this trend simply featured excess fabric gathered and draped at the back of a dress. Eventually, though, skirts were puffed up with large cushions filled with straw. Ladies who wore them ended up with exaggerated figures with outthrust hindquarters. The bustle was frequently a target of ridicule. This style

reminds me of the “padded seat” of modern day leggings, though the modern day version isn’t quite so exaggerated. In 1868, Laura Redden Searing, using the pen name Howard Glyndon, wrote about the agony young women put themselves through for fashion in the New York Times, “If you knew the Spartan courage which is required to go through an ordeal of this sort for two or three hours at a time, you would not wonder that she has not an idea left in her head after her daily display is over,” she said. Hahahaha!! That sounds reasonable to me.

reminds me of the “padded seat” of modern day leggings, though the modern day version isn’t quite so exaggerated. In 1868, Laura Redden Searing, using the pen name Howard Glyndon, wrote about the agony young women put themselves through for fashion in the New York Times, “If you knew the Spartan courage which is required to go through an ordeal of this sort for two or three hours at a time, you would not wonder that she has not an idea left in her head after her daily display is over,” she said. Hahahaha!! That sounds reasonable to me.

Most of us who were around in the 1960s, know about the early space program, and especially the very first American to orbit the Earth…John Glenn. John Glenn’s historic flight put the United States on the map of the space race, so to speak. It all seems very commonplace in this day and age of space shuttles, and the International Space Station, but the reality was that this first American orbit could have ended tragically.

Most of us who were around in the 1960s, know about the early space program, and especially the very first American to orbit the Earth…John Glenn. John Glenn’s historic flight put the United States on the map of the space race, so to speak. It all seems very commonplace in this day and age of space shuttles, and the International Space Station, but the reality was that this first American orbit could have ended tragically.

While some change had happened concerning blacks and women, there was still much that had not changed. Women were not viewed as mathematically inclined, and black women even less so. That was before they knew about Katherine Johnson. Katherine Johnson was handpicked to be one of three black students to integrate West Virginia’s graduate schools. Born in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia in 1918, her intense curiosity and brilliance with numbers vaulted her ahead several grades in school. She graduated from high school at the age of 14, and the historically black West Virginia State University at 18, where she had made quick work of the school’s math curriculum. Katherine graduated with highest honors in 1937 and took a job teaching at a black public school in Virginia, but this was not to be her career.

In 1935, the NACA (National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, a precursor to NASA) hired five women to be their first computer pool at the Langley campus. “The women were meticulous and accurate…and they didn’t have to pay them very much,” NASA’s historian Bill Barry says, explaining the NACA’s decision. Six months later, after the attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into World War II, NACA and Langley began recruiting African-American women with college degrees to work as human computers.

Johnson was hired by NACA in 1953. Johnson, along with Dorothy Vaughan, and Mary Jackson, became part of NASA’s team of human computers. These people were mathematicians who performed the necessary calculations to make space flight possible in a time when “machine computers” didn’t exist, or were very new. Johnson was perfect for this job. After working for Nasa a while, and really proving her worth, Johnson was still running into road blocks. When NASA engineer Paul Stafford was preparing a meeting about John Glenn’s upcoming mission. Johnson felt that she needed to be at that meeting to explain her numbers, but Stafford refused her the request to attend stating, “There’s no protocol for women attending.” Johnson instantly replied, “There’s no protocol for a man circling Earth either, sir.”

Johnson saw an opportunity when NASA installed huge IBM computers…that no one knew how to use. They tried to get the machines set up so that the human computers could be replaced by the far more accurate machines, but the set up proved too difficult, until Johnson taught herself to use the machines. She then taught the rest of the black women, human computers to run them too. In the end, they were the only ones who knew how to do it. It made them much more important to the space program. The men had to face the fact that the women, that they had all but discounted, were going to be the ones to save the space program.

The biggest highlight of Katherine Johnson’s career came at the point when John Glenn was getting ready to  make that historic first orbit around the Earth. Johnson’s main job in the lead-up and during the mission was to double-check and reverse engineer the newly-installed IBM 7090s trajectory calculations. There were very tense moments during the flight that forced the mission to end earlier than expected. John Glenn requested that Johnson specifically check and confirm trajectories and entry points that the IBM put out. Glenn didn’t completely trust the computer. So, he asked the head engineers to “get the girl to check the numbers…If she says the numbers are good…I’m ready to go.” Johnson couldn’t have been given a greater seal of approval than to have John Glenn say that she was the only one he trusted…after all, it was his life.

make that historic first orbit around the Earth. Johnson’s main job in the lead-up and during the mission was to double-check and reverse engineer the newly-installed IBM 7090s trajectory calculations. There were very tense moments during the flight that forced the mission to end earlier than expected. John Glenn requested that Johnson specifically check and confirm trajectories and entry points that the IBM put out. Glenn didn’t completely trust the computer. So, he asked the head engineers to “get the girl to check the numbers…If she says the numbers are good…I’m ready to go.” Johnson couldn’t have been given a greater seal of approval than to have John Glenn say that she was the only one he trusted…after all, it was his life.

During World War I, Britain, like the United States would have to do in World War II, had to employ large numbers of women into jobs vacated by men who had gone to fight in the war. They also had to create new jobs as part of the war effort. As an example, women were hired in munitions factories. The high demand for weapons resulted in the munitions factories becoming the largest single employer of women during 1918. It was a job that many people resisted, mainly because it was seen as “men’s work.” When I think about the work these women were doing, I find myself much more concerned with the toxicity and danger of the materials they were working with, than whether or not the job should be done by a man. Of course, the materials would present the same danger to the men, but the men had always felt like the dangerous work should fall to them.

During World War I, Britain, like the United States would have to do in World War II, had to employ large numbers of women into jobs vacated by men who had gone to fight in the war. They also had to create new jobs as part of the war effort. As an example, women were hired in munitions factories. The high demand for weapons resulted in the munitions factories becoming the largest single employer of women during 1918. It was a job that many people resisted, mainly because it was seen as “men’s work.” When I think about the work these women were doing, I find myself much more concerned with the toxicity and danger of the materials they were working with, than whether or not the job should be done by a man. Of course, the materials would present the same danger to the men, but the men had always felt like the dangerous work should fall to them.

Nevertheless, with the introduction of conscription in 1916 everything changed. Conscription refers to the process of automatically calling up men and women for military service. During the First World War men (it only applied to men at this time) who were conscripted into the armed forces had no choice but to go and fight, even if they did not want to. Around 1916, with the need becoming serious, the government began  coordinating the employment of women through campaigns and recruitment drives. This led to women working in areas of work that were formerly reserved for men. Jobs such as, for example railway guards, ticket collectors, buses, tram conductors, postal workers, police, firefighters, as well as bank tellers and clerks. Some women also worked heavy or precision machinery in engineering, led cart horses on farms, and worked in the civil service and factories.

coordinating the employment of women through campaigns and recruitment drives. This led to women working in areas of work that were formerly reserved for men. Jobs such as, for example railway guards, ticket collectors, buses, tram conductors, postal workers, police, firefighters, as well as bank tellers and clerks. Some women also worked heavy or precision machinery in engineering, led cart horses on farms, and worked in the civil service and factories.

By 1917 the British munitions factories, which by this time, primarily employed women workers, produced 80% of the weapons and shells used by the British Army. The women working there soon became known as “canaries” because they had to handle TNT (the chemical compound trinitrotoluene that is used as an explosive agent in munitions) which caused their skin to turn yellow. The nickname might have been a cute joke, but the job the women did was far from funny. These women risked their lives working with poisonous substances without adequate protective clothing or the required safety measures, that we know are needed now. During the years of World War I, around 400 women died from overexposure to TNT. I wonder too, how many died in  the years that followed the war, from exposure to the same chemicals that had killed the original 400 women.

the years that followed the war, from exposure to the same chemicals that had killed the original 400 women.

As if the dangerous working conditions weren’t enough, women were also paid significantly less than men in comparable positions. In 1918, women workers on London’s buses, trams, and subways organized a strike and managed to win equal pay for equal work. When the war ended, many women were fired to free up jobs for returning veterans. Some thanks that was. I’m sure many of the women were glad to go back to their prior jobs, or go home to take care of their families, but to be fired” was just wrong in every way. Nevertheless, in return for their hard work, these women were fired so that the returning men could have a job again.

These days, with all the television shows about secret agents, undercover cops, and spies, most of us wouldn’t think twice about one of those positions being held by a woman. During the American Civil War, however, which basically coincided with the Victorian era, one of the most morally repressive eras in history for women, things were different. Everything from a woman’s dress to her education were tightly constricted by moral attitudes that governed her every action. Basically, women were to concentrate their “war efforts” on the task of supporting their husband, brothers, or fathers, in whatever their beliefs were toward the matter. However, as the war dragged on and more men were called into active duty, the farms, factories, stores, and schools were left without workers, so the women stepped up to stand in the gap, as it were. This was most surprising because, back then, women were considered too frail, and their minds too simple for things like politics and war. They were designed for keeping the home and taking care of the babies. Nevertheless, when the men were called into active duty, most of them would have lost their farms, homes, and businesses had it not been for the strength and intelligence of the of the “frail and simple” women. Many women refused to limit their assistance to their country to what could be accomplished close to home. Some of them became nurses, worked to raise supplies for their troops, or even worked in armories, but there was a number of these women decided to support their country in a more dangerous…and scandalous way…they became spies.Back then, espionage was considered a very dishonorable pursuit for a man during the Civil War era, but for a woman…it was tantamount to prostitution. Nevertheless, with the war raging, women of both the North and South flaunted the Victorian morality of the time to provide their country the intelligence it needed to make tactical and practical decisions.

These days, with all the television shows about secret agents, undercover cops, and spies, most of us wouldn’t think twice about one of those positions being held by a woman. During the American Civil War, however, which basically coincided with the Victorian era, one of the most morally repressive eras in history for women, things were different. Everything from a woman’s dress to her education were tightly constricted by moral attitudes that governed her every action. Basically, women were to concentrate their “war efforts” on the task of supporting their husband, brothers, or fathers, in whatever their beliefs were toward the matter. However, as the war dragged on and more men were called into active duty, the farms, factories, stores, and schools were left without workers, so the women stepped up to stand in the gap, as it were. This was most surprising because, back then, women were considered too frail, and their minds too simple for things like politics and war. They were designed for keeping the home and taking care of the babies. Nevertheless, when the men were called into active duty, most of them would have lost their farms, homes, and businesses had it not been for the strength and intelligence of the of the “frail and simple” women. Many women refused to limit their assistance to their country to what could be accomplished close to home. Some of them became nurses, worked to raise supplies for their troops, or even worked in armories, but there was a number of these women decided to support their country in a more dangerous…and scandalous way…they became spies.Back then, espionage was considered a very dishonorable pursuit for a man during the Civil War era, but for a woman…it was tantamount to prostitution. Nevertheless, with the war raging, women of both the North and South flaunted the Victorian morality of the time to provide their country the intelligence it needed to make tactical and practical decisions.

The most famous of these female spies was Belle Boyd…born Marie Isabella Boyd. She began spying for the Confederacy when Union troops invaded her Martinsburg, Virginia home in 1861. One of the Federal soldiers manhandled her mother, and Boyd shot and killed him. She was exonerated in the soldier’s death, and an emboldened Boyd managed to befriend the Union soldiers left to guard her, and used her slave, Eliza, to pass information confided in her by the soldiers along to Confederate officers. Boyd was caught at her first attempt at spying, and threatened with death, but she did not stop her activities. She vowed to find a better way instead. She began eavesdropping on union officers staying at her father’s hotel. She learned enough to inform General Stonewall Jackson about their regiment and activities. Taking no chances, this time, Boyd delivered her intelligence firsthand, moving through Union lines, and reportedly drawing close enough to the action to return with bullet holes in her skirts. The information she provided allowed the Confederate army to advance on Federal troops at Fort Royal. Boyd’s daring acts of espionage soon caught up with her again and when a beau gave her up to Union authorities in 1862, she was arrested and held in the Old Capitol Prison in Washington for a month. Then she released, but found herself in the arrested again soon after. Once again, she managed to be set free, and this time she traveled to England, where amazingly, she married not a Confederate soldier, but a Union officer.

Boyd wasn’t the only spy in the Civil War. Another famous female spy was nicknamed “Crazy Bet,” but her real  name was Elizabeth Van Lew. Van Lew was born to a wealthy and prominent Richmond family, and was educated by Quakers in Philadelphia. When she returned to Richmond, she had become an abolitionist. She even went so far as to convince her mother to free the family’s slaves. Her espionage activity began soon after the start of the war. Her neighbors were appalled, because she openly supported the Union. She concentrated her efforts on aiding Federal prisoners at the Libby Prison, by taking them food, books, and paper. Later, she smuggled information about Confederate activities from the prisoners to Union officers, including General Ulysses S. Grant. To hide her activities from her Confederate neighbors, she behaved oddly. She dressed in old clothes, talking to herself, and refusing to comb her hair. Believe it or not, people began to think she was insane. They started calling her “Crazy Bet.” Van Lew wasn’t insane, in fact, she was incredibly intelligent. She was hailed by Grant as the provider of some of the most important intelligence gathered during the war.

name was Elizabeth Van Lew. Van Lew was born to a wealthy and prominent Richmond family, and was educated by Quakers in Philadelphia. When she returned to Richmond, she had become an abolitionist. She even went so far as to convince her mother to free the family’s slaves. Her espionage activity began soon after the start of the war. Her neighbors were appalled, because she openly supported the Union. She concentrated her efforts on aiding Federal prisoners at the Libby Prison, by taking them food, books, and paper. Later, she smuggled information about Confederate activities from the prisoners to Union officers, including General Ulysses S. Grant. To hide her activities from her Confederate neighbors, she behaved oddly. She dressed in old clothes, talking to herself, and refusing to comb her hair. Believe it or not, people began to think she was insane. They started calling her “Crazy Bet.” Van Lew wasn’t insane, in fact, she was incredibly intelligent. She was hailed by Grant as the provider of some of the most important intelligence gathered during the war.

The Old West was a wild, untamed place, and the people who lived there had to be tough as nails too. During that time, the Indian Territory, now Oklahoma, was considered the most violent of the American territories. Along with the Indians, it served as home to hundreds of outlaws from around the country. These were hardened criminal men, accused of murder, rape, robbery, arson, adultery, bribery, and numerous other crimes. They headed to the Indian Territory, looking for a place to hideout…a place where the lawmen couldn’t follow. The Indian Territory was without law enforcement with the exception of the Indian Nations’ police forces, who had no jurisdiction over the many criminals who had taken flight from other states. It left the outlaws in a place of sweet freedom, from both types of law.

The Old West was a wild, untamed place, and the people who lived there had to be tough as nails too. During that time, the Indian Territory, now Oklahoma, was considered the most violent of the American territories. Along with the Indians, it served as home to hundreds of outlaws from around the country. These were hardened criminal men, accused of murder, rape, robbery, arson, adultery, bribery, and numerous other crimes. They headed to the Indian Territory, looking for a place to hideout…a place where the lawmen couldn’t follow. The Indian Territory was without law enforcement with the exception of the Indian Nations’ police forces, who had no jurisdiction over the many criminals who had taken flight from other states. It left the outlaws in a place of sweet freedom, from both types of law.

Then Judge Isaac Parker was appointed to the Western Judicial District of Arkansas, which included Indian Territory. All that sweet freedom was about to end. Parker decided to bring law and order to the Indian Territory…or at least to the criminal element of it. He commanded about 200 deputy marshals to “clean up” the lawless territory. It was a noble idea that would take years to accomplish, as the deputies struggled to cover some 74,000 square miles in their search for hundreds of wanted fugitives. The occupation of a U.S. Deputy Marshal courted constant danger, so much so that between 1872 and 1896, over 100 deputies died enforcing the law throughout the territory. A number of men made names for themselves working as U.S. Marshals in the Indian Territory. Men such as Heck Thomas, Bass Reeves, Bill Tilghman, Chris Madsen, and dozens of others.

There were also a number of other U.S. Marshals who, more quietly made names for themselves, mainly because they were women. I think that as a woman, I would not be so inclined to head into Indian Territory in those days to “clean up” the place. Women have long been considered a part of the “clean up” crew, but most of the time, it was as homemakers. I don’t think anyone thought they could be successful law enforcement officers…at least not in those days.

One of these brave women was F.M. Miller, who was appointed as a U.S. Deputy Marshal out of the federal court at Paris, Texas in 1891. When she was commissioned, she was the only female deputy working in Indian Territory. She was known to have accompanied Campbell on all his trips. During her tenure, she was mentioned in several newspaper articles including the Fort Smith Elevator on November 6, 1891 that described here as: “a dashing brunette of charming manners.” The article continued by stating: “The woman carries a pistol buckled around her and has a Winchester strapped to her saddle. She is an expert shot and a superb horsewoman, and brave to the verge of recklessness. It is said that she aspires to win a name equal to that of Belle Starr, differing from her by exerting herself to run down criminals and in the enforcement of the law.”

Another article appeared a couple of weeks later in the Muskogee Phoenix on November 19, 1891, which said that she had the reputation of being a fearless and efficient officer and had locked up more than a few offenders. The article continued: “Miss Miller is a young woman of prepossessing appearance, wears a cowboy hat and is always adorned with a pistol belt full of cartridges and a dangerous looking Colt pistol which she knows how to use. She has been in Muskogee for a few days, having come here with Deputy Marshal Cantrel, a guard with some prisoners brought from Talahina. Regarding Miss. Miller’s unique position as Deputy U.S. Marshal, another newspaper commented, “Hopefully in the future, there will be more information on this colorful peace officer.”

Another female U.S Marshal in Indian Territory who showed bravery and skill in her job was a young woman named Ada Curnutt. The daughter of a Methodist minister, Ada Curnutt moved to the Oklahoma Territory with her sister and brother-in-law shortly after it opened for settlers. The 20 year old soon found work as the Clerk of the District Court in Norman, Oklahoma and as a Deputy Marshal to U.S. Marshal William Grimes. Her most famous arrest occurred in March, 1893 when she received a telegram from Grimes, instructing her to send a deputy to Oklahoma City to bring in two notorious outlaws named Reagan and Dolezal who were wanted for forgery. I seriously doubt that Grimes meant for her to go, but all the other deputies were out in the field so Curnutt stepped up to the responsibility. She quickly boarded a train for Oklahoma City. When she arrived she discovered that the two men were in a saloon and quickly made her way there. Upon her arrival she asked a man on the street to go in and tell them that a lady needed to see them outside. The outlaws eagerly went out to meet her. When the two emerged, Ada read the warrants to them and stated that they were under arrest. Heavily armed, the two men laughed at the young woman and thinking it was a joke. They stupidly allowed her to place handcuffs over their wrists. When the captives began to realize that the joke was on them, Curnutt announced to the crowd gathered around them that she was prepared to deputize every man to aide her, if needed. As it turns out, it was not necessary, as she escorted them to the the train station and telegraphed the marshal’s office in Guthrie that she was bringing them in. She was 24 years old at the time. The two forgers  were soon tried and convicted. “Like all deputies of her era, she had to be extremely tough and ready to face a wide range of situations,” the U.S. Marshals Service wrote of Carnutt.

were soon tried and convicted. “Like all deputies of her era, she had to be extremely tough and ready to face a wide range of situations,” the U.S. Marshals Service wrote of Carnutt.

While it was unusual, there were a number of women in law enforcement, even before it was widely accepted as normal. All these women forged the way for the many women we have in law enforcement, and even in the military today. these women may have been the “clean up” crew, but they were a tough as nail clean up crew, and they made, and continue to make, history in the field of law enforcement, and in the military.

World War II saw many changes in how women were viewed in the normally male-dominated world. With so many men off fighting the war, the women stepped up to do the jobs of riveters in the shipyards, and they stepped up in many other occupations too. If there are no men to do the jobs, someone had to keep the country running, and the United States found out that women were up for the task. I don’t suppose that everyone thought that women could do it, but they simply had no choice. World War II was the largest and most violent armed conflict in the history of mankind. This war taught us, not only about the profession of arms, but also about military preparedness, global strategy, and combined operations in the coalition war against fascism.

World War II saw many changes in how women were viewed in the normally male-dominated world. With so many men off fighting the war, the women stepped up to do the jobs of riveters in the shipyards, and they stepped up in many other occupations too. If there are no men to do the jobs, someone had to keep the country running, and the United States found out that women were up for the task. I don’t suppose that everyone thought that women could do it, but they simply had no choice. World War II was the largest and most violent armed conflict in the history of mankind. This war taught us, not only about the profession of arms, but also about military preparedness, global strategy, and combined operations in the coalition war against fascism.

Prior 1942, the only way for women to be involved in the service was as an Army Nurse, in the Army Nurse Corps, but early in 1941 Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts met with General George C. Marshall, the Army’s Chief of Staff, and told him that she intended to introduce a bill to establish an Army women’s corps, separate and distinct from the existing Army Nurse Corps. Congress approved that bill on May 14, 1942, and the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was born. The WAAC bill became law on May 15, 1942. Congressional opposition to the bill centered around southern congressmen. With women in the armed services, one representative asked, “Who will then do the cooking, the washing, the mending, the humble homey tasks to which every woman has devoted herself; who will nurture the children?” These days he would have been run out of Congress for having backward ideas but it was a different time, and one that some women of today truly miss…especially young mothers.

After a long and bitter debate which filled ninety-eight columns in the Congressional Record, the bill finally passed the House 249 to 86. The Senate approved the bill 38 to 27 on May 14. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the bill into law the next day, he set a recruitment goal of 25,000 for the first year. WAAC recruitment topped that goal by November of 1942, at which point Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson authorized WAAC enrollment at 150,000, the original ceiling set by Congress. The day the bill became law, Stimson appointed Oveta Culp Hobby as Director of the WAAC. As chief of the Women’s Interest Section in the Public Relations Bureau at the War Department, Hobby had helped shepherd the WAAC bill through Congress. She had impressed both the media and the public when she testified in favor of the WAAC bill in January. In the words of the Washington Times Herald, “Mrs. Hobby has proved that a competent, efficient woman who works longer days than the sun does not need to look like the popular idea of a competent, efficient woman.” Women would go on to not only become competent and efficient, but requested…sometimes above the men!!

So, what led to the Army’s decision to enlist women during World War II? The answer is simple. The “unfathomable” became reality, as the Army struggled to fulfill wartime quotas from an ever-shrinking pool of candidates. By mid-1943, the Army was simply running out of eligible white men to enlist. The Army could scarcely spare those men already in the service for non-combatant duties. General Dwight D. Eisenhower remarked: “The simple headquarters of a Grant or Lee were gone forever. An Army of filing clerks, stenographers, office managers, telephone operators, and chauffeurs had become essential, and it was scarcely

less than criminal to recruit these from needed manpower when great numbers of highly qualified women were available.” While women played a vital role in the success of World War II, their admission into combat roles would not come for many years, and many weren’t sure it was a good idea when it did. The WAC, as a branch of the service, was disbanded in 1978 and all female units were integrated with male units.

less than criminal to recruit these from needed manpower when great numbers of highly qualified women were available.” While women played a vital role in the success of World War II, their admission into combat roles would not come for many years, and many weren’t sure it was a good idea when it did. The WAC, as a branch of the service, was disbanded in 1978 and all female units were integrated with male units.

Seldom, if ever, do you see a minor political party that is able to obtain national support for their way of doing things, but that did happen in the 1920s. The Prohibition Party (PRO) is a political party in the United States best known for its historic opposition to the sale or consumption of alcoholic beverages. It is the oldest existing third party in the US. The party was an integral part of the temperance movement. I suppose it depends on which side you were on, as to how you feel about alcohol, but the reality is that they most likely didn’t have the support of the majority of the American citizens.

Seldom, if ever, do you see a minor political party that is able to obtain national support for their way of doing things, but that did happen in the 1920s. The Prohibition Party (PRO) is a political party in the United States best known for its historic opposition to the sale or consumption of alcoholic beverages. It is the oldest existing third party in the US. The party was an integral part of the temperance movement. I suppose it depends on which side you were on, as to how you feel about alcohol, but the reality is that they most likely didn’t have the support of the majority of the American citizens.

Nevertheless, on Saturday, January 7, 1920, the Manchester Guardian reported with a level of mild shock on one of the most extraordinary experiments in modern democratic history. “One minute after midnight tonight,” the story began, “America will become an entirely arid desert as far as alcoholics are concerned, any drinkable containing more than half of 1 per cent alcohol being forbidden.” In fact, the Volstead Act, which prohibited the sale of “intoxicating liquors,” had come into operation at midnight the day before. But the authorities had granted drinkers one last day, one last session at the bar, before the iron shutters of Prohibition came down.

I don’t really know how I feel about the comparison between the prohibition of alcohol, and the war on drugs (specifically Marijuana), but one thing can be said for sure. With the law that made these things illegal, came, by natural progression, the gangs or gangsters, who illegally made a way for those things to be obtained by the people. As to Prohibition, the 20s were filled with bootleggers, gangsters, and illegal purchases of alcohol…hence the Roaring Twenties.

Across the United States, many bars and restaurants marked the demise of the demon drink by handing out free glasses of wine, brandy and whisky. Others saw one last opportunity to make a killing, charging an eye-watering “20 to 30 dollars for a bottle of champagne, or a dollar to two dollars for a drink of whisky”. In some establishments, mournful dirges played while coffins were carried through the crowds of drinkers. In others, the walls were hung with black crepe. And in the most prestigious establishments, the Guardian noted, placards carried the ominous words: “Exit booze. Doors close on Saturday.” It was like an Irish wake for the deceased.

The prohibition of alcohol lasted for almost 14 years, and with it came a violent era in out country’s history. Gangsters like Al Capone, Bugsy Segal, Lucky Luciano, Meyer Lansky, Johnny Torrio, Arnold Rothstein, Bugs Moran, Enoch “Nucky” Johnson, and the mafia sprung into action…refusing to be railroaded. Prohibition’s largely Protestant champions, a large proportion of whom were high-minded, middle-class women. were the do-gooders of the day. Often deeply religious, they saw Prohibition as a kind of social reform, a crusade to clean up the American city and restore the founding virtues of the godly republic. The gangsters, gangs, and the mafia saw it as a declaration of war, and acted accordingly. Stills were built, and bootleggers financed.

Before long violence broke out as the runners were caught and the gangsters lost their product. Nevertheless, for 14 long years, Prohibition persisted, until there was finally enough pull in Congress. The 21st Amendment to the United States Constitution is ratified on December 5, 1933, repealing the 18th Amendment and bringing an end to the era of national prohibition of alcohol in America. At 5:32pm EST, Utah became the 36th state to ratify the amendment, achieving the requisite three-fourths majority of states’ approval. Pennsylvania and Ohio had ratified it earlier in the day.

Before long violence broke out as the runners were caught and the gangsters lost their product. Nevertheless, for 14 long years, Prohibition persisted, until there was finally enough pull in Congress. The 21st Amendment to the United States Constitution is ratified on December 5, 1933, repealing the 18th Amendment and bringing an end to the era of national prohibition of alcohol in America. At 5:32pm EST, Utah became the 36th state to ratify the amendment, achieving the requisite three-fourths majority of states’ approval. Pennsylvania and Ohio had ratified it earlier in the day.

First chronicled by the famous western writer, Zane Grey, in his 1934 novel The Code of the West, no “written” code ever actually existed. However, the hardy pioneers who lived in the west were bound by these unwritten rules that centered on hospitality, fair play, loyalty, and respect for the land. These days, little of that code remains, or so it seems. These days, the more someone can get away with, he better they seem to like it. That just wasn’t the case for the people of thee old West. They needed to know that they could count on their neighbors, friends, and yes, even strangers

First chronicled by the famous western writer, Zane Grey, in his 1934 novel The Code of the West, no “written” code ever actually existed. However, the hardy pioneers who lived in the west were bound by these unwritten rules that centered on hospitality, fair play, loyalty, and respect for the land. These days, little of that code remains, or so it seems. These days, the more someone can get away with, he better they seem to like it. That just wasn’t the case for the people of thee old West. They needed to know that they could count on their neighbors, friends, and yes, even strangers

Ramon Adams, a Western historian, explained it best in his 1969 book, The Cowman and His Code of Ethics, saying, in part: “Back in the days when the cowman with his herds made a new frontier, there was no law on the range. Lack of written law made it necessary for him to frame some of his own, thus developing a rule of behavior which became known as the “Code of the West.” These homespun laws, being merely a gentleman’s agreement to certain rules of conduct for survival, were never written into statutes, but were respected everywhere on the range.”

Though the cowman might break every law of the territory, state and federal government, he took pride in upholding his own unwritten code. His failure to abide by it did not bring formal punishment, but the man who broke it became, more or less, a social outcast. His friends “hazed him into the cutbacks” and he was subject to the punishment of the very code he had broken. Though the Code of the West was always unwritten, here is a “loose” list of some of the guidelines: Don’t inquire into a person’s past. Take the measure of a man for what he is today. Never steal another man’s horse. A horse thief pays with his life. Defend yourself whenever  necessary. Look out for your own. Remove your guns before sitting at the dining table. Never order anything weaker than whiskey. Don’t make a threat without expecting dire consequences. Never pass anyone on the trail without saying “Howdy”. When approaching someone from behind, give a loud greeting before you get within shooting range. Don’t wave at a man on a horse, as it might spook the horse. A nod is the proper greeting. After you pass someone on the trail, don’t look back at him…it implies you don’t trust him. Riding another man’s horse without his permission is nearly as bad as making love to his wife. Never even bother another man’s horse. Always fill your whiskey glass to the brim. A cowboy doesn’t talk much; he saves his breath for breathing. No matter how weary and hungry you are after a long day in the saddle, always tend to your horse’s needs before your own, and get your horse some feed before you eat. Cuss all you want, but only around men, horses and cows. Complain about the cooking and you become the cook. Always drink your whiskey with your gun hand, to show your friendly intentions. Do not practice ingratitude. A cowboy is pleasant even when out of sorts. Complaining is what quitters do, and cowboys hate quitters. Always be courageous. Cowards aren’t tolerated in any outfit worth its salt. A cowboy always helps someone in need, even a stranger or an enemy. Never try on another man’s hat. Be hospitable to strangers. Anyone who wanders in, including an enemy, is welcome at the dinner table. The same was true for riders who joined cowboys on the range. Give your enemy a fighting chance. Never wake another man by shaking or touching him, as he might wake suddenly and shoot you. Real cowboys are modest. A braggart who is “all gurgle and no guts” is not tolerated. Be there for a friend when he needs you. Drinking on duty is grounds for instant dismissal and blacklisting. A cowboy is loyal to his “brand,” to his friends, and those he rides with. Never shoot an unarmed or unwarned enemy. This was also known as “the rattlesnake code”: always warn before you strike. However, if a man was being stalked, this could be ignored. Never shoot a woman no matter what.

necessary. Look out for your own. Remove your guns before sitting at the dining table. Never order anything weaker than whiskey. Don’t make a threat without expecting dire consequences. Never pass anyone on the trail without saying “Howdy”. When approaching someone from behind, give a loud greeting before you get within shooting range. Don’t wave at a man on a horse, as it might spook the horse. A nod is the proper greeting. After you pass someone on the trail, don’t look back at him…it implies you don’t trust him. Riding another man’s horse without his permission is nearly as bad as making love to his wife. Never even bother another man’s horse. Always fill your whiskey glass to the brim. A cowboy doesn’t talk much; he saves his breath for breathing. No matter how weary and hungry you are after a long day in the saddle, always tend to your horse’s needs before your own, and get your horse some feed before you eat. Cuss all you want, but only around men, horses and cows. Complain about the cooking and you become the cook. Always drink your whiskey with your gun hand, to show your friendly intentions. Do not practice ingratitude. A cowboy is pleasant even when out of sorts. Complaining is what quitters do, and cowboys hate quitters. Always be courageous. Cowards aren’t tolerated in any outfit worth its salt. A cowboy always helps someone in need, even a stranger or an enemy. Never try on another man’s hat. Be hospitable to strangers. Anyone who wanders in, including an enemy, is welcome at the dinner table. The same was true for riders who joined cowboys on the range. Give your enemy a fighting chance. Never wake another man by shaking or touching him, as he might wake suddenly and shoot you. Real cowboys are modest. A braggart who is “all gurgle and no guts” is not tolerated. Be there for a friend when he needs you. Drinking on duty is grounds for instant dismissal and blacklisting. A cowboy is loyal to his “brand,” to his friends, and those he rides with. Never shoot an unarmed or unwarned enemy. This was also known as “the rattlesnake code”: always warn before you strike. However, if a man was being stalked, this could be ignored. Never shoot a woman no matter what.

Consideration for others is central to the code, such as: Don’t stir up dust around the chuck wagon, don’t wake  up the wrong man for herd duty, etc. Respect the land and the environment by not smoking in hazardous fire areas, disfiguring rocks, trees, or other natural areas. Honesty is absolute – your word is your bond, a handshake is more binding than a contract. Live by the Golden Rule. “The Code of the West was a gentleman’s agreement to certain rules of conduct. It was never written into the statutes, but it was respected everywhere on the range.“ Ramon F. Adams

up the wrong man for herd duty, etc. Respect the land and the environment by not smoking in hazardous fire areas, disfiguring rocks, trees, or other natural areas. Honesty is absolute – your word is your bond, a handshake is more binding than a contract. Live by the Golden Rule. “The Code of the West was a gentleman’s agreement to certain rules of conduct. It was never written into the statutes, but it was respected everywhere on the range.“ Ramon F. Adams

As I read through these “codes,” I have to think just how sad it is that so little of that beautiful code is practiced these days, and how very sad that is.