wilhelm brasse

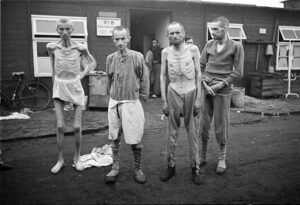

Using prisoners-of-war as free labor in the concentration camps was not an unheard of practice during World War II. Many of the prisoners in Auschwitz were forced to do administrative and labor duties, such as sorting new arrivals’ possessions, constructing and expanding the camps, and taking photos of the other captives. In the photo lab at Auschwitz alone, nearly 39,000 prison photographs were taken. The problem with those photos was that when the Nazis began to realize that they were going to lose the war, they knew that all those photos were proof positive of their guilt in the matter of the Holocaust. That meant that the photos had to be destroyed.

Using prisoners-of-war as free labor in the concentration camps was not an unheard of practice during World War II. Many of the prisoners in Auschwitz were forced to do administrative and labor duties, such as sorting new arrivals’ possessions, constructing and expanding the camps, and taking photos of the other captives. In the photo lab at Auschwitz alone, nearly 39,000 prison photographs were taken. The problem with those photos was that when the Nazis began to realize that they were going to lose the war, they knew that all those photos were proof positive of their guilt in the matter of the Holocaust. That meant that the photos had to be destroyed.

During the evacuation of Auschwitz in 1945, photo lab workers Wilhelm Brasse and Bronislaw Jureczek were ordered to burn all photographic evidence. The men knew that to do so would mean that the Nazis would get away with the heinous murders they had committed. So, they came up with a way to save the pictures. They placed wet photo paper at the bottom of the furnace before placing the real pictures inside. With the furnace so packed and the wet paper creating so much smoke, the blaze went out quickly. Then, once they were unsupervised, the men were able to take the unharmed pictures from the furnace to smuggle them out. The precious pictures of victims of the Holocaust were then cataloged, and have been kept in the Archives of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.

On July 11, 1944, evidence of mass murder of Jews at the extermination camp was provided to Winston Churchill by four escapees from Auschwitz. For two years, the Nazis had managed to keep the gas chambers in Auschwitz, southern Poland, a secret. Churchill wrote to his Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, “There is no doubt this is probably the greatest and most horrible crime ever committed in the whole history of the world…all concerned in this crime who may fall into our hands, including people who only obeyed orders by carrying out the butcheries, should be put to death.”

Auschwitz was the principal Nazi extermination camp in World War II. The complex covered at least 15 square miles. As World War II was coming to a close, and the Nazis were fleeing their own demise, the camp was evacuated, there were about 67,000 inmates who were still alive there. About 56,000 of these are led away. The rest were too sick to move, so they were left behind to die. As many as 250,000 people will die on the roads before the end of the war. Originally, the site for Auschwitz was chosen because the main railway lines from Germany and Poland passed through the area. By taking the prisoners to Poland, the Nazis hoped to keep their existence a secret. When the prisoners were sent to Auschwitz, they actually had to pay their own way…to be stuffed into a cattle car, so tightly that they couldn’t even fall down if they passed out or died. Prisoners deported to Auschwitz went there to die. The Nazis had no plans for them to survive. Auschwitz contained five crematoria, made and patented by German engineering company Töpf and Sons. It was estimated that they could dispose of 4,756 corpses a day. The crimes against humanity that had been committed here were atrocious, and panic had set in among the SS guards, who feared for their lives at the hands of the ruthless Red Army when it arrived.

For the prisoners, the end was also in sight, either by death, or by liberation for the few survivors of one of humanity’s most vile atrocities. The snow across the grounds of Auschwitz was deep, and temperatures are well below freezing. The Soviet Red Army was only a few miles away. Many SS officers and their families had already left, with cases full of valuables stolen from murdered inmates. Those on the death marches from Auschwitz survived by eating the snow on the shoulders of the people in front of them, because if they bent down to pick up the slush they risked being shot. As the prisoners marched slowly west through Poland, SS Lieutenant Colonel Rudolf Höss was heading in the opposite direction. Höss had been given the task of building Auschwitz by Himmler and had been the camp’s brutal commandant, living in luxury with his wife and five children just 100 yards from the camp grounds. After consideration, he headed back to Auschwitz, past what he described as “stumbling columns of corpses,” to make sure all evidence linking him to the genocide had been destroyed. But Höss was forced to turn his car around as the Russians advanced toward him. In 1946, he was captured and a year later hanged at Auschwitz.

Inmates, Brasse and Jureczek employed at Auschwitz’s Identification Service saved the thousands of negatives

of prisoners’ ID photographs, at great personal risk to themselves, and because they did, at least some of the guilty ones could be held accountable. The photos were intended to be a way to identify prisoners if they escaped, but their rapid starvation made these images useless. Nevertheless, Brasse and Jureczek were keen on preserving evidence of the atrocities at Auschwitz, and in the end, their efforts paid off.

of prisoners’ ID photographs, at great personal risk to themselves, and because they did, at least some of the guilty ones could be held accountable. The photos were intended to be a way to identify prisoners if they escaped, but their rapid starvation made these images useless. Nevertheless, Brasse and Jureczek were keen on preserving evidence of the atrocities at Auschwitz, and in the end, their efforts paid off.