washington dc

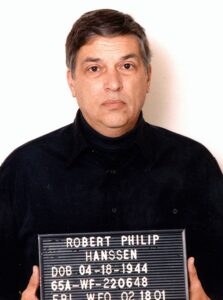

When the FBI began to suspect that they had a mole in the mid-1980s, they assigned the investigation to FBI Agent Robert Philip Hanssen. Hanssen was born April 18, 1944, in Chicago, Illinois, to a Lutheran family that lived in the Norwood Park neighborhood. He was of Norwegian descent. His father, Howard, who died 1993, was a Chicago police officer, and was allegedly emotionally abusive to Hanssen during his childhood. Nevertheless, Hanssen went on to graduate from William Howard Taft High School in 1962 and attended Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois. He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1966. Hanssen joined the FBI in 1976. Things were going well for him in the FBI, but then, something changed.

When the FBI began to suspect that they had a mole in the mid-1980s, they assigned the investigation to FBI Agent Robert Philip Hanssen. Hanssen was born April 18, 1944, in Chicago, Illinois, to a Lutheran family that lived in the Norwood Park neighborhood. He was of Norwegian descent. His father, Howard, who died 1993, was a Chicago police officer, and was allegedly emotionally abusive to Hanssen during his childhood. Nevertheless, Hanssen went on to graduate from William Howard Taft High School in 1962 and attended Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois. He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1966. Hanssen joined the FBI in 1976. Things were going well for him in the FBI, but then, something changed.

In 1979, just three years after joining the FBI, Hanssen approached the Soviet Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU) to offer his services. It is thought that he may have had some financial difficulties, and this meeting became the beginning of his first espionage cycle, lasting until 1981. After that, he laid low for a while. Then, in 1981, he restarted his espionage activities and continued until 1991. After that, he ended communications during the collapse of the Soviet Union, because he was afraid that he would be exposed. Hanssen restarted communications the next year and continued until his arrest. Throughout his spying, he remained anonymous to the Russians.

Hanssen spied for Soviet and Russian intelligence services against the United States from 1979 to 2001. His espionage was described by the Department of Justice as “possibly the worst intelligence disaster in US history.” In all, he sold about six thousand classified documents to the KGB that detailed US strategies in the event of nuclear war, developments in military weapons technologies, and aspects of the US counterintelligence program. Hanssen was involved in espionage at the same time as Aldrich Ames in the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Both Ames and Hanssen compromised the names of KGB agents working secretly for the United States. Some of those KGB agents were executed for their betrayal. Hanssen also revealed a multimillion-dollar eavesdropping tunnel built by the FBI under the Soviet Embassy. Then in 1994, Ames was arrested. At that time, some of these intelligence breaches remained unsolved, so the search began for another spy. Ironically, they chose the spy himself to search for the spy. How convenient it was for Hanssen. Finally, the FBI paid $7 million to a KGB agent to obtain a file on an anonymous mole. That information led to Janssen’s exposure, when he was identified through fingerprint and voice analysis.

On February 18, 2001, Hanssen was arrested at Foxstone Park, near his home in the Washington DC, suburb of

Vienna, Virginia, after leaving a package of classified materials at a dead drop site. Following his arrest, he was charged with selling US intelligence documents to the Soviet Union and subsequently Russia for more than $1.4 million in cash, diamonds, and Rolex watches over a period of twenty-two years. Hanssen pleaded guilty to fourteen counts of espionage and one of conspiracy to commit espionage, to avoid the death penalty. He was sentenced to fifteen life terms without the possibility of parole and was incarcerated at ADX Florence until his death on June 5, 2023.

Vienna, Virginia, after leaving a package of classified materials at a dead drop site. Following his arrest, he was charged with selling US intelligence documents to the Soviet Union and subsequently Russia for more than $1.4 million in cash, diamonds, and Rolex watches over a period of twenty-two years. Hanssen pleaded guilty to fourteen counts of espionage and one of conspiracy to commit espionage, to avoid the death penalty. He was sentenced to fifteen life terms without the possibility of parole and was incarcerated at ADX Florence until his death on June 5, 2023.

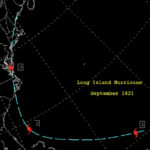

The normal hurricane season is from June 1 to November 30, and since we have our first hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico right now, it looks like it’s right on time. Nevertheless, for places like New York, where it is normally a little cooler, the hurricane season starts a little later, and may not really arrive at all. However, on June 4, 1825, a rare early hurricane arrived, moving off the East Coast and tracking south of New York. The hurricane caused several ship wrecks, and killed seven people.

The normal hurricane season is from June 1 to November 30, and since we have our first hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico right now, it looks like it’s right on time. Nevertheless, for places like New York, where it is normally a little cooler, the hurricane season starts a little later, and may not really arrive at all. However, on June 4, 1825, a rare early hurricane arrived, moving off the East Coast and tracking south of New York. The hurricane caused several ship wrecks, and killed seven people.

The National Hurricane Center, states that on average, hurricane winds have impacted the New York City area every 19 years, and major hurricanes, of a Category 3 or higher, only every 74 years. The highest hurricane reading, Category 5 hurricane is not expected to occur there at all, because of the climate conditions there.

Nevertheless, on June 4, 1825, forming ahead of what is now considered hurricane season, a severe tropical storm surprised the Atlantic seaboard from Florida to New York City. At that time, they did not have the prediction capabilities, and this storm was first sighted near Santo Domingo on May 28th. It moved across Cuba on June 1st, with gale force winds,  beginning at Saint Augustine, and approaching US soil on the June 2nd, and impacting Charleston, North Carolina on June 3rd.

beginning at Saint Augustine, and approaching US soil on the June 2nd, and impacting Charleston, North Carolina on June 3rd.

The tide in North Carolina rose six feet at New Bern and fourteen feet at Adams Creek. As the tide rushed in, more than 25 ships were driven ashore at Ocracoke, 27 near Washington, and also some at New Bern. The plantations on the coastal areas near the South River were inundated with water, causing a heavy loss of crops and livestock. New Bern experienced heavy damage near the waterfront.

The storm pummeled Norfolk, with horrific force for 27 hours as the storm passed by to the east beginning on the  morning of June 3rd. The wind was relentless, uprooting trees as it went. At noon on June 4th, stores on the wharves were flooded in a surge up five feet deep. High winds howled through the Washington DC area. The storm then moved northeast past Nantucket on June 5th.

morning of June 3rd. The wind was relentless, uprooting trees as it went. At noon on June 4th, stores on the wharves were flooded in a surge up five feet deep. High winds howled through the Washington DC area. The storm then moved northeast past Nantucket on June 5th.

The storm reminded many people of the September gale of 1821, except that the September gale would have been much more common. There haven’t been many early June hurricanes in that area since 1825, but there have been a number of hurricanes to hit the area since, including Hurricane Sandy, which did much damage in New York City, including the subway area.

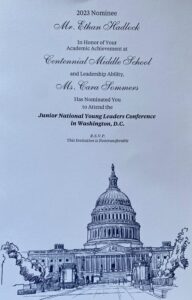

My grandnephew, Ethan Hadlock is just growing up so fast…in more ways than one. He is in his last year of middle school, which means this is his final semester of 8th grade. The fact that he is going to be in high school next year would probably be more shocking to people were it not for his size. Ethan is on track to stand around 6 foot 5 inches or so, like his dad, Ryan Hadlock and his grandpa, Chris Hadlock. He isn’t there yet, of course, but he is taller than most 8th grade boys, making him look like a high school student already. His parents are finding it difficult to keep him in jeans these days. He not only outgrows them, but the waist to length ratio is hard to find. Right now, he wears a 29/34…and is quickly heading for 29/36. Another fact that I find surprising, is that Ethan is already growing a mustache!! When a guy can do that in middle school, it is always shocking. It just doesn’t seem like that should be happening with a middle school boy, but there it is…literally!!

My grandnephew, Ethan Hadlock is just growing up so fast…in more ways than one. He is in his last year of middle school, which means this is his final semester of 8th grade. The fact that he is going to be in high school next year would probably be more shocking to people were it not for his size. Ethan is on track to stand around 6 foot 5 inches or so, like his dad, Ryan Hadlock and his grandpa, Chris Hadlock. He isn’t there yet, of course, but he is taller than most 8th grade boys, making him look like a high school student already. His parents are finding it difficult to keep him in jeans these days. He not only outgrows them, but the waist to length ratio is hard to find. Right now, he wears a 29/34…and is quickly heading for 29/36. Another fact that I find surprising, is that Ethan is already growing a mustache!! When a guy can do that in middle school, it is always shocking. It just doesn’t seem like that should be happening with a middle school boy, but there it is…literally!!

Ethan has been having great time expanding his horizons. He is playing percussion in band and is very much enjoying that. He comes from a musical family, so his talent in that area is not surprising. Another area in which Ethan has shown himself to be exceptional is in the area of leadership. In fact, his leadership has been so noticed that he was just selected for the Junior National Young Leadership Conference in Washington DC. We are all so proud of Ethan. He is a kind person and a natural leader. Ethan has long exhibited leadership capabilities, so while I’m surprised about the DC tri, it is only because I didn’t know kids his age went on these things. For Ethan to be

chosen is not really surprising at all. That is just how Ethan is.

chosen is not really surprising at all. That is just how Ethan is.

Ethan got a nerf gun for Christmas and has been playing with it a lot. While lots of kids would shoot the nerf bullets at other people, Ethan is the exception to that rule. He doesn’t shoot at people, a fact that shows maturity, and it makes me proud of him. Ethan is such a sweet young man. He cares about those around him…especially his little sister, for whom he has always been a guardian angel. He loves his grandparents, his aunts and uncles, and his great aunts and uncles. He never hesitates to give a hug when he greets them. He doesn’t care if they who sees him. He’s not shy about expressing his love for his family…they are very important to him. And he is very important to all of us too. Today is Ethan’s 14th birthday. Happy birthday Ethan!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

To call the Pearl Harbor attack, a “mistake on the part of the Japanese,” seems like a case of serious misinformation, on the part of the one who made such a comment, Admiral Chester A Nimitz. Nevertheless, that is what he said on Christmas Day, 1941, after he toured the destruction of his new duty station shortly after his Christmas Eve arrival. Anyone who would have heard Nemitz comments probably thought the new Commander of the Pacific Fleet might be just a little bit “off his rocker!!” Where everyone else saw all the ships sunken and knew of the 3,800 men who lost their lives that day, and in their minds, there was nothing good about all this, so what was the admiral thinking.

To call the Pearl Harbor attack, a “mistake on the part of the Japanese,” seems like a case of serious misinformation, on the part of the one who made such a comment, Admiral Chester A Nimitz. Nevertheless, that is what he said on Christmas Day, 1941, after he toured the destruction of his new duty station shortly after his Christmas Eve arrival. Anyone who would have heard Nemitz comments probably thought the new Commander of the Pacific Fleet might be just a little bit “off his rocker!!” Where everyone else saw all the ships sunken and knew of the 3,800 men who lost their lives that day, and in their minds, there was nothing good about all this, so what was the admiral thinking.

Sunday, December 7th, 1941, found Admiral Chester Nimitz attending a concert in Washington, DC. He received a page and was told that he had a phone call. On the other end was President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who told Admiral Nimitz that his new assignment was to be the Commander of the Pacific Fleet. Admiral Nimitz flew to Hawaii to assume command of the Pacific Fleet, arriving to see such a spirit of despair, dejection, and defeat. It seemed that everyone thought the Japanese had already won the war. As the tour boat returned to dock, the young helmsman of the boat asked, “Well Admiral, what do you think after seeing all this destruction?” The admiral’s reply shocked everyone within the sound of his voice. Admiral Nimitz said, “The Japanese made three of the biggest mistakes an attack force could ever make, or God was taking care of America. Which do you think it was?” Shocked and surprised, the young helmsman asked, “What do mean by saying the Japanese made the three biggest mistakes an attack force ever made?”

What was meant, is really the difference between the thinking of an enlisted man, and the thinking of a great strategist, such as Admiral Nemitz was. I’m actually quite sure most of us would have fallen more in line with

the enlisted helmsman…basically seeing the trees and missing the forest. So, Admiral Nemitz had to enlighten those around him. The first mistake made by the Japanese, is actually one I had heard before, and likely the “best” mistake for the people concerned. The attack on Pearl Harbor took place on a Sunday morning…when many of the men who might have been on the ships, were on leave. In fact, nine out of ten of the men stationed on the ships were on leave. That cut the loss of life down by 90%. As Admiral Nemitz told the people, “If those same ships had been lured to sea and been sunk–we would have lost 38,000 men instead of 3,800.” Now the Japanese had angered the “Sleeping Giant” that was the United States and left the majority of the fighting force to exact their revenge.

the enlisted helmsman…basically seeing the trees and missing the forest. So, Admiral Nemitz had to enlighten those around him. The first mistake made by the Japanese, is actually one I had heard before, and likely the “best” mistake for the people concerned. The attack on Pearl Harbor took place on a Sunday morning…when many of the men who might have been on the ships, were on leave. In fact, nine out of ten of the men stationed on the ships were on leave. That cut the loss of life down by 90%. As Admiral Nemitz told the people, “If those same ships had been lured to sea and been sunk–we would have lost 38,000 men instead of 3,800.” Now the Japanese had angered the “Sleeping Giant” that was the United States and left the majority of the fighting force to exact their revenge.

Of course, that was only their first mistake. Their second mistake was that when the Japanese saw all those battleships lined up in a row, they got so carried away sinking the battleships, they either didn’t notice, or forgot about the dry docks opposite those ships. Leaving the dry docks, meant that instead of towing every one of those ships to the America to be repaired, they could simply be raised from the shallow water they were in, and one tug could pull them over to the dry docks. Any salvageable ships could be repaired and back out at sea by the time they could have towed them to the America. Add that fact to the already established fact that Admiral Nemitz already had crews ashore anxious to man those ships. They were ready to fight.

The final mistake made by the Japanese was that they were either unaware of or forgot about the above-ground fuel storage tanks located just five miles away over the next hill. In fact, every drop of fuel in the Pacific theater of war was sitting out there in those tanks, and even if the ships were ready to go and fully manned, the lack of fuel would have prevented an attack on the Japanese fleet.

While everyone around him was thinking of the devastation and the defeat of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Admiral Nemitz saw the three biggest mistakes of the Japanese government, or as he preferred to call it, that

“God was taking care of America.” I tend to agree with Admiral Nemitz in that I, too, think it was God taking care of us. My thought is that the Japanese knew about the dry docks and the fuel storage, but in their “excitement” at pulling off the surprise attack, they forgot all about them. Of course, there is that first mistake of planning an attack of God’s Day. Seriously, they chose to take on the whole Pacific Fleet…and God too!! Wow!! It’s hard to be more “stupid” than that.

“God was taking care of America.” I tend to agree with Admiral Nemitz in that I, too, think it was God taking care of us. My thought is that the Japanese knew about the dry docks and the fuel storage, but in their “excitement” at pulling off the surprise attack, they forgot all about them. Of course, there is that first mistake of planning an attack of God’s Day. Seriously, they chose to take on the whole Pacific Fleet…and God too!! Wow!! It’s hard to be more “stupid” than that.

The United States Navy ship USS Knox (FF-1052) was named for Commodore Dudley Wright Knox, who was an officer in the United States Navy during the Spanish-American War and World War I. Born in Fort Walla Walla, Washington, on June 21, 1877, Knox was also a prominent naval historian. For many years he oversaw the Navy Department’s historical office, now called the Naval Historical Center. I can’t say for sure, nor exactly how, but I suspect that Dudley Wright Knox is somehow related to my husband, Bob Schulenberg’s Knox side of the family. That will be a subject I will need to explore further in the future.

The United States Navy ship USS Knox (FF-1052) was named for Commodore Dudley Wright Knox, who was an officer in the United States Navy during the Spanish-American War and World War I. Born in Fort Walla Walla, Washington, on June 21, 1877, Knox was also a prominent naval historian. For many years he oversaw the Navy Department’s historical office, now called the Naval Historical Center. I can’t say for sure, nor exactly how, but I suspect that Dudley Wright Knox is somehow related to my husband, Bob Schulenberg’s Knox side of the family. That will be a subject I will need to explore further in the future.

Knox attended school in Washington DC and graduated from the United States Naval Academy on June 5, 1896. Following his graduation, he served in the Spanish-American War aboard the screw steamer Maple in Cuban waters. A screw steamer or screw steamship is an old term for a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine, using one or more propellers…also known as screws…to propel it through the water. These ships were nicknamed iron screw steam ship.

His was a long and distinguished career. During the Philippine-American War, Knox commanded the gunboat Albay, and during the Chinese Boxer Rebellion, the gunboat Iris. He then commanded three of the Navy’s first destroyers…Shubrick, Wilkes, and Decatur. Following his attendance and graduation from the Naval War College in 1912–13, Knox became the aide to Captain William Sims, commanding the Atlantic Torpedo Flotilla. During the cruise of the “Great White Fleet,” he was sent around the world by President Theodore Roosevelt, as an ordnance officer on the battleship Nebraska (BB-14).

He took the lead in developing naval operational doctrine when he published an article of great influence in the US Naval Institute Proceedings in 1915. He was Fleet Ordnance Officer in both the Atlantic and the Pacific, serving in the Office of Naval Intelligence, and commanding the Guantanamo Bay Naval Station. The job of a Fleet Ordnance Officers is to ensure that weapons systems, vehicles, and equipment are ready and available…and in perfect working order, at all times. These officers also manage the developing, testing, fielding, handling, storage, and disposal of munitions. In November 1917, Knox joined the staff of, by then, Admiral William Sims, Commander of US Naval Forces in European Waters. Knox earned the Navy Cross for “distinguished service” while serving as Aide in the Planning Section and later in the Historical Section. He was promoted to Captain on  February 1, 1918. In March 1919, Knox returned to the United States. He served for a year on the faculty of the Naval War College, where he was a key figure on the Knox-King-Pye Board that examined professional military education. In 1920–21, he commanded the armored cruiser Brooklyn (ACR-3), then the protected cruiser Charleston (C-22) before resuming duty in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations.

February 1, 1918. In March 1919, Knox returned to the United States. He served for a year on the faculty of the Naval War College, where he was a key figure on the Knox-King-Pye Board that examined professional military education. In 1920–21, he commanded the armored cruiser Brooklyn (ACR-3), then the protected cruiser Charleston (C-22) before resuming duty in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations.

Also in 1920, Knox first began his work as a naval publicist, serving as naval editor of the Army and Navy Journal until 1923. He then became the naval correspondent of the Baltimore Sun in 1924 – 1946, and naval correspondent of the New York Herald Tribune in 1929. While he was transferred to the Retired List of the Navy on October 20, 1921, he actually and strangely continued on active duty, serving simultaneously as Officer in Charge, Office of Naval Records and Library, and as Curator for the Navy Department. Knox played a key role in creating the Naval Historical Foundation. Early in World War II, he was assigned additional duty as Deputy Director of Naval History.

In a career that spanned half of a century, Knox’s leadership inspired diligence, efficiency, and initiative while he guided, improved, and expanded the Navy’s archival and historical operations. Knox had personal connections to President Roosevelt, Fleet Admiral Ernest J King, and other senior leaders in the Navy Department. These relationships allowed him to play an instrumental role, albeit behind the scenes in the years leading up to and during World War II.

Knox published a number of writings and several books…including his first book “The Eclipse of American Sea Power” (1922) and “A History of the United States Navy” (1936). “A History of the United States Navy” is recognized as “the best one-volume history of the United States Navy in existence.” Through his personal connection with President Roosevelt, he was able to publish key, multi-volume collections of documents on  naval operations in The Quasi-War with France in 1798–1800, the first Barbary war and the second Barbary War…stories that may not have been told, had he not taken the initiative.

naval operations in The Quasi-War with France in 1798–1800, the first Barbary war and the second Barbary War…stories that may not have been told, had he not taken the initiative.

November 2, 1945, found Knox promoted to Commodore, and awarded the Legion of Merit for “exceptionally meritorious conduct” while directing the correlation and preservation of accurate records of the US naval operations in World War II, thus protecting this vital information for posterity. Finally, on June 26, 1946, Knox was relieved of all active-duty work. He died in Bethesda, Maryland, on June 11, 1960. His cause of death is listed as unknown. He was 83 years old.

As disastrous fires go, the Great Baltimore Fire comes in historically as the third worst conflagration in an American city, surpassed only by the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, and the San Francisco Earthquake and Fire of 1906. There were other major urban disasters that were comparable in cost, but not fires. These were the Galveston Hurricane of 1900 and most recently, Hurricane Katrina that hit New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico coast in August 2005.

As disastrous fires go, the Great Baltimore Fire comes in historically as the third worst conflagration in an American city, surpassed only by the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, and the San Francisco Earthquake and Fire of 1906. There were other major urban disasters that were comparable in cost, but not fires. These were the Galveston Hurricane of 1900 and most recently, Hurricane Katrina that hit New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico coast in August 2005.

On February 7, 1904, a small fire was reported at the John Hurst and Company building on West German Street at Hopkins Place, The site is currently the Royal Farms Arena in the western part of downtown Baltimore. The fire started at about 10:48am, and quickly spread. It wasn’t long before the fire surpassed the ability of the city’s firefighting resources, and calls for help were telegraphed to other cities. By 1:30pm, units from Washington, DC were arriving on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad at Camden Street Station. Officials decided to use a firebreak in an effort to halt the fires progression. They dynamited buildings around the existing fire. Unfortunately, this tactic was unsuccessful. The fire continued to rage and spread until it was finally brought under control about 5:00pm on February 8, 1904.

In the end, the fire engulfed a large portion of the city that evening. The culprit for starting the fire is believed to have been a discarded cigarette in the basement of the Hurst Building. When the fire was finally out after burning for 31 hours, an 80-block area of downtown Baltimore, stretching from the waterfront to Mount Vernon on Charles Street, had been destroyed. More than 1,500 buildings were completely leveled, and some 1,000 severely damaged, bringing property loss from the disaster to an estimated $100 million. No lives were lose in this disaster…miraculously, although some reports did claim one man died, but that was not confirmed. The fire raged from North Howard Street in the west and southwest, the flames spread north through the retail shopping area as far as Fayette Street and began moving eastward, pushed along by the prevailing winds. Amazingly, it narrowly missed the new 1900 Circuit Courthouse…now known as the Clarence M. Mitchell, Jr. Courthouse. The fire passed the historic Battle Monument Square from 1815 to 1827 at North Calvert Street, and the quarter-century-old  Baltimore City Hall of 1875 on Holliday Street; and finally spread further east to the Jones Falls stream which divided the downtown business district from the old East Baltimore tightly-packed residential neighborhoods of Jonestown…also known as Old Town and newly named Little Italy.” The fire burned as far south as the wharves and piers lining the north side of the old “Basin,” now the “Inner Harbor” of the Northwest Branch of the Baltimore Harbor and Patapsco River facing along Pratt Street. Also spared was Baltimore’s domed City Hall, built in 1867. The Great Baltimore Fire was the most destructive fire in the United States since the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, It destroyed most of the city and caused an estimated $200 million in property damage.

Baltimore City Hall of 1875 on Holliday Street; and finally spread further east to the Jones Falls stream which divided the downtown business district from the old East Baltimore tightly-packed residential neighborhoods of Jonestown…also known as Old Town and newly named Little Italy.” The fire burned as far south as the wharves and piers lining the north side of the old “Basin,” now the “Inner Harbor” of the Northwest Branch of the Baltimore Harbor and Patapsco River facing along Pratt Street. Also spared was Baltimore’s domed City Hall, built in 1867. The Great Baltimore Fire was the most destructive fire in the United States since the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, It destroyed most of the city and caused an estimated $200 million in property damage.

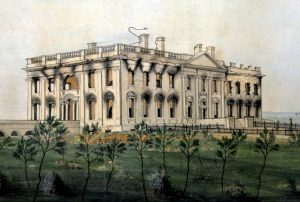

It was a long time coming. An actual house for the President of the United States was a long time coming. Prior to establishing the nation’s capital in Washington DC, the United States Congress and its predecessors had met in Philadelphia (Independence Hall and Congress Hall), New York City (Federal Hall), and a number of other locations (York, Pennsylvania; Lancaster, Pennsylvania; the Maryland State House in Annapolis, Maryland; and Nassau Hall in Princeton, New Jersey). Then, it was decided that our government needed a permanent home. Washington DC was selected.

It was a long time coming. An actual house for the President of the United States was a long time coming. Prior to establishing the nation’s capital in Washington DC, the United States Congress and its predecessors had met in Philadelphia (Independence Hall and Congress Hall), New York City (Federal Hall), and a number of other locations (York, Pennsylvania; Lancaster, Pennsylvania; the Maryland State House in Annapolis, Maryland; and Nassau Hall in Princeton, New Jersey). Then, it was decided that our government needed a permanent home. Washington DC was selected.

The first president who would have an actual government-owned home in Washington DC was President John Adams, and he would only live there for the last year of his only term in office. President John Adams, in the last year of his only term as president, moved into the newly constructed President’s House on November 1, 1800. The President’s House was the original name for what is known today as the White House. Adams and his wife had been living in temporarily at Tunnicliffe’s City Hotel near the half-finished Capitol building since June 1800, when the federal government  was moved from Philadelphia to the new capital city of Washington DC. When Adams first arrived in Washington, he wrote to his wife Abigail, who was still at their home in Quincy, Massachusetts, that he was pleased with the new site for the federal government and that he had explored the soon-to-be President’s House and liked it.

was moved from Philadelphia to the new capital city of Washington DC. When Adams first arrived in Washington, he wrote to his wife Abigail, who was still at their home in Quincy, Massachusetts, that he was pleased with the new site for the federal government and that he had explored the soon-to-be President’s House and liked it.

Although workmen had rushed to finish plastering and painting walls before Adams returned to DC from a visit to Quincy in late October, the construction was still unfinished when Adams rolled up in his carriage on November 1. However, the furniture from their Philadelphia home was in place and a portrait of George Washington was already hanging in one room. It was a decent start. The next day, Adams sent a note to Abigail, who would arrive in Washington later that month, saying that he hoped “none but honest and wise men [shall] ever rule under this roof.” I wish that  had always been the case, and of course the idea of good and bad presidents are often a matter of opinion.

had always been the case, and of course the idea of good and bad presidents are often a matter of opinion.

The President’s House though new had its issues. Adams was initially very pleased with the presidential mansion, but he and Abigail found it to be cold and damp during the winter. Abigail wrote to a friend saying that the building was tolerable only so long as fires were lit in every room. She also said that on a funny note, she also said that she had to hang their washing in an empty “audience room,” which is the current East Room. Now, that’s quite a thought. During the War of 1812, the White House was set on fire by the British, and had to be repaired.

On September 11th, I wrote about the significance if the September 11th date and the terrorist attacks on New York City and the Pentagon, but there was another target that day. The attack on Washington DC was at first thought to be planned for the White House, but it was later determined that the attack was planned for the nation’s capitol building. I have wondered if that September 11th date could have a significance for the capitol too, so I did some research. Unfortunately, I have not been able to find a specific day that the groundbreaking at the capital took place.

On September 11th, I wrote about the significance if the September 11th date and the terrorist attacks on New York City and the Pentagon, but there was another target that day. The attack on Washington DC was at first thought to be planned for the White House, but it was later determined that the attack was planned for the nation’s capitol building. I have wondered if that September 11th date could have a significance for the capitol too, so I did some research. Unfortunately, I have not been able to find a specific day that the groundbreaking at the capital took place.

I did find out that on September 18, 1793, George Washington laid the cornerstone to the United States Capitol building. Now, I’m not a contractor, but it makes sense to me that from groundbreaking to cornerstone, could logically take a week…putting the possible groundbreaking on…you guessed it, September 11, 1793. The building itself would take nearly a century to complete, as architects came and went, the British set fire to it, and it was called into use during the Civil War. Nevertheless, the original groundbreaking took place before September 18, 1793. Today, the Capitol building, with its famous cast-iron dome and important collection of American art, is part of the Capitol Complex, which includes six Congressional office buildings and three Library of Congress buildings, all developed in the 19th and 20th centuries.

As we all know, the brave heroes of Flight 93 foiled that attack on September 11, 2001, which is why the US Capitol building was not destroyed or damaged. Those people saved the capitol building and somehow managed t crash their plane into a field…hitting no one on the ground. They knew that the other planes that had been hijacked, were not landing to have their demands met…they were being flown into buildings, and that meant that they were likely headed for the same fate. They knew that all they could do was to sacrifice their own lives to make sure that this attack did not succeed, and that is what they did, crashing it into a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania. With a quick, “Let’s roll!!” they ran forward and fought with the terrorists, and while they weren’t able to get complete control of the plane, they made sure it didn’t reach it’s intended destination, and they saved the capital.

I can’t say, for sure, that September 11th was the date that they broke ground on the capital building, but in

my mind, it makes sense that it was. And that makes it shocking to me. There were some days in Islamic history about September 11, but they were simply battles and such that took place, not the day that a city or place that was being attacked…also being the day that it was founded or had it’s groundbreaking. That makes it monumental, but in the third attack, they weren’t successful, and the plane crashed in a field. Maybe that was monumental too.

my mind, it makes sense that it was. And that makes it shocking to me. There were some days in Islamic history about September 11, but they were simply battles and such that took place, not the day that a city or place that was being attacked…also being the day that it was founded or had it’s groundbreaking. That makes it monumental, but in the third attack, they weren’t successful, and the plane crashed in a field. Maybe that was monumental too.

Recently, I became interested is unusual military bases, after coming across on called RAF Rudloe Manor…an English military base that looked, and in fact was an old English manor. Another military base, this one in the United States, in Virginia, near Dulles International Airport, has now come to my attention, but for multiple reasons. Mount Weather Emergency Operations Center is a civilian command facility in the US Commonwealth of Virginia, used as the center of operations for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Also known as the High Point Special Facility (HPSF), its preferred designation since 1991 is “SF”.

Recently, I became interested is unusual military bases, after coming across on called RAF Rudloe Manor…an English military base that looked, and in fact was an old English manor. Another military base, this one in the United States, in Virginia, near Dulles International Airport, has now come to my attention, but for multiple reasons. Mount Weather Emergency Operations Center is a civilian command facility in the US Commonwealth of Virginia, used as the center of operations for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Also known as the High Point Special Facility (HPSF), its preferred designation since 1991 is “SF”.

Mount Weather Emergency Operations Center gained some “fame” for a completely different reason in 1974. December 1, 1974 was a windy, stormy day in the Washington DC area. Trans World Airlines Flight 514 was en route from Indianapolis, Indiana, and Columbus, Ohio, to Washington Dulles International Airport, but was originally supposed to land at Washington National Airport. The Boeing 727-231, registration N54328, was diverted to Dulles when high crosswinds, east at 32 mph and gusting to 56 mph, prevented safe operations on the main north-south runway at Washington National. The flight was being vectored for a non-precision instrument approach to runway 12 at Dulles. Air traffic controllers cleared the flight down to 7,000 feet before clearing them for the approach while not on a published segment. At this point, there was some confusion in the cockpit over whether they were still under a radar-controlled approach segment which would allow them to descend safely, or not. The jetliner began a descent to 1,800 feet, shown on the first checkpoint for the published approach. After reaching 1,800 feet there were some 100 to 200 foot altitude deviations which the flight crew discussed as encountering heavy downdrafts and reduced visibility in snow. Nevertheless, their tower controlled approach had ended.

In the stormy conditions, late on that Sunday morning, the aircraft was in controlled flight, when it impacted a low mountain about thirty miles northwest of its revised destination. That mountain was Mount Weather, Virginia, where the Mount Weather Emergency Operations Center was located. The plane impacted the west slope of Mount Weather at 1,670 feet above sea level at approximately 265 mph. The wreckage was contained within an area about 900 by 200 feet. The evidence of first impact were trees sheared off about 70 feet above the ground…the elevation at the base of the trees was 1,650 feet. All 92 aboard, 85 passengers and seven crew members, were killed. “The wreckage path was oriented along a line 118 degrees magnetic. Calculations indicated that the left wing went down about six degrees as the aircraft passed through the trees and the aircraft was descending at an angle of about one degree. After about five hundred feet of travel through the trees, it struck a rock outcropping at an elevation of about 1,675 feet. Numerous heavy components of the aircraft were thrown forward of the outcropping, and numerous intense post-impact fires broke out which were later extinguished. The mountain’s summit is at 1,754 feet above sea level.”

“The accident investigation board was split in its decision as to whether the flight crew or Air Traffic Control were responsible. The majority absolved the controllers as the plane was not on a published approach segment; the dissenting opinion was that the flight had been radar vectored. Terminology between pilots and controllers differed without either group being aware of the discrepancy. It was common practice at the time for controllers to release a flight to its own navigation with “Cleared for the approach,” and flight crews commonly believed that was also authorization to descend to the altitude at which the final segment of the approach began. No clear indication had been given by controllers to Flight 514 that they were no longer on a radar vector segment and therefore responsible for their own navigation. Procedures were clarified after this accident. Controllers now state, “Maintain (specified altitude) until established on a portion of the approach,” and pilots now understand that previously assigned altitudes prevail until an altitude change is authorized on the published approach segment the aircraft is currently flying. Ground proximity detection equipment was also mandated for the airlines.”

During the NTSB investigation, it was discovered that a United Airlines flight had very narrowly escaped the same fate during the same approach and at the same location only six weeks prior. Apparently, the problem was bigger than it was first thought to be. The crash is also noteworthy, because of the accident location. The undesired attention to the Mount Weather facility, became the unfortunate side effect, because the site was the linchpin of plans implemented by the federal government to ensure continuity in the event of a nuclear war.

The crash did not damage the facility, since most of its features were underground. Only its underground main phone line was severed, with service to the complex being restored by C&P Telephone within 2½ hours after the crash. Nevertheless, the crash brought to light the possibility of damage to an important facility by a plane crash, which was a distinct possibility due to the flight path of planes landing at Dulles International Airport.

The crash did not damage the facility, since most of its features were underground. Only its underground main phone line was severed, with service to the complex being restored by C&P Telephone within 2½ hours after the crash. Nevertheless, the crash brought to light the possibility of damage to an important facility by a plane crash, which was a distinct possibility due to the flight path of planes landing at Dulles International Airport.

Since people began moving around the world there was a need for mail service, but people hated to wait months to hear from their loved ones…especially if it was with bad news. There had to be a way to get he mail faster and with the invention of the airplane, in late 1903, the possibility of a new way to deliver the mail was on the horizon. It really didn’t take very long for someone to make the metal leap from driving the mail to flying the mail from place to place. Where there is a need, there must be a solution. That solution came on May 15, 1918, when the United States officially established airmail service between New York and Washington DC, using Army aircraft and pilots. Prior to this date, the Post Office Department used new transportation systems such as railroads or steamboats to transport mail. They contracted with the owners of the lines to carry the mail. There were no commercial airlines to contract with, so no one had thought about that yet, but that was about to change.

Since people began moving around the world there was a need for mail service, but people hated to wait months to hear from their loved ones…especially if it was with bad news. There had to be a way to get he mail faster and with the invention of the airplane, in late 1903, the possibility of a new way to deliver the mail was on the horizon. It really didn’t take very long for someone to make the metal leap from driving the mail to flying the mail from place to place. Where there is a need, there must be a solution. That solution came on May 15, 1918, when the United States officially established airmail service between New York and Washington DC, using Army aircraft and pilots. Prior to this date, the Post Office Department used new transportation systems such as railroads or steamboats to transport mail. They contracted with the owners of the lines to carry the mail. There were no commercial airlines to contract with, so no one had thought about that yet, but that was about to change.

Army Major Reuben H. Fleet was charged with setting up the first US airmail service, scheduled to operate beginning May 15, 1918 between Washington DC, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and New York City. The army pilots chosen to fly that day were Lieutenants Howard Culver, Torrey Webb, Walter Miller and Stephen Bonsal, all chosen by Major Fleet, and Lieutenants James Edgerton and George Boyle, both chosen by postal officials. Edgerton and Boyle had only recently graduated from the flight school at Ellington Field, Texas and neither had more than 60 hours of piloting time. While I’m sure they were a bit nervous, I’m also sure they were excited to be standing on the threshold of history.

The project got off to a bit of an embarrassingly rocky start, when Lieutenant Boyle, who was engaged to the daughter of Interstate Commerce Commissioner Charles McChord, was selected to pilot the first plane out of Washington DC that day. After all his preparations, Boyle hopped into his plane and was unable to start it. The plane had not been fueled. I’m sure that added a bit of nervousness to the situation. Nevertheless, he finally got his Curtiss Jenny, loaded with 124 pounds of airmail, into the air and made his way to Washington DC. His assignment was to fly to Philadelphia, the mid-way stop between the Washington and New York ends of the service. He did not make it there that day. The novice pilot got lost and low on gas, crash landed in rural Maryland, less than 25 miles away from Washington.

Fortunately for the service, the other flights operated as scheduled that day. Thanks to his political connections, Lieutenant Boyle was given a second chance to fly the airmail out of Washington DC. This time, he was given an escort who flew him out of the city, having given him directions to “follow the Chesapeake Bay” towards Philadelphia. Unfortunately, Boyle followed those instructions too literally, following the curve of the bay over to Maryland’s eastern shore, where he landed, out of fuel again. Not even Boyle’s connections could help him now, and he was removed from the pilots list for the service. I’m sure that didn’t help his standing with his future father-in-law either.

The other rookie pilot, Lieutenant James Edgerton, did much better on his flights and stayed with the service. Edgerton managed to keep his plane aloft during a violent storm that struck while he was on another flight, even as the propeller was pelted by hail. He stayed with the mail service until the next year, and became the Chief of Flying Operations. Then in August, the Post Office Department took over airmail operations with airplanes and civilian pilots of its own. Captain Benjamin Lipsner was named the first superintendent of the U.S. Airmail Service.

The first flight operated by the Post Office Department took off from College Park, Maryland, on August 12, 1918. The destination was New York. Max Miller flew that historic flight. Miller flew the new Curtiss R-4 aircraft. These new planes had more powerful Liberty 400 horsepower engines. Miller was the first pilot hired by the Post Office Department. He died when his plane caught fire and crashed on September 1, 1920. The Post Office Department decided to launch pathfinding flights from New York to Chicago in September 1918. A major obstacle was the Allegheny Mountains, considered by some to be the most dangerous territory on the route. U.S. Airmail Service Superintendent Benjamin Lipsner chose two of his best pilots, Eddie Gardner and Max Miller, for these flights. Eager competitors, Gardner and Miller turned the test into a race. On September 5,  1918, the pair left New York. Miller flew in a Standard airmail plane with a 150-horsepower Hispano-Suiza engine. Gardner followed in a Curtiss R-4 with a 400-horsepower Liberty engine and was accompanied by Eddie Radel, a mechanic. As each pilot landed to refuel or make repairs, he eagerly called Lipsner in Chicago to find out where the other one was. A set of telegrams now in the National Postal Museum tracked their progress. Miller landed in Chicago first, at 6:55 p.m. on September 6. Gardner arrived the next morning, landing at 8:17 at Grant Park. Sometimes it isn’t about the size of the engine I guess. Of course, today, very few people use the postal service, not called “snail mail.” With the internet and texting we have almost instant access to our loved ones.

1918, the pair left New York. Miller flew in a Standard airmail plane with a 150-horsepower Hispano-Suiza engine. Gardner followed in a Curtiss R-4 with a 400-horsepower Liberty engine and was accompanied by Eddie Radel, a mechanic. As each pilot landed to refuel or make repairs, he eagerly called Lipsner in Chicago to find out where the other one was. A set of telegrams now in the National Postal Museum tracked their progress. Miller landed in Chicago first, at 6:55 p.m. on September 6. Gardner arrived the next morning, landing at 8:17 at Grant Park. Sometimes it isn’t about the size of the engine I guess. Of course, today, very few people use the postal service, not called “snail mail.” With the internet and texting we have almost instant access to our loved ones.