u-boats

There are some national events that stay in our thoughts and hearts forever. The Pearl Harbor is one of those events. The attack on Pearl Harbor was so destructive and so unexpected that it shocked everyone…well, most everyone anyway. President Franklin D Roosevelt knew that Japan would likely attack, but thought it would be in the western Pacific Ocean, especially the Philippians. Pearl Harbor was considered an unlikely target. Roosevelt wanted to enter the war, but he wanted to attack Germany, whom he considered to be the bigger threat. In fact, he had ordered the attack on any U-Boats found in the west side of the Atlantic. So, technically the US was already in the war…most people just didn’t know that. Still, the attack on Pearl Harbor was horrific and the United States had to retaliate.

There are some national events that stay in our thoughts and hearts forever. The Pearl Harbor is one of those events. The attack on Pearl Harbor was so destructive and so unexpected that it shocked everyone…well, most everyone anyway. President Franklin D Roosevelt knew that Japan would likely attack, but thought it would be in the western Pacific Ocean, especially the Philippians. Pearl Harbor was considered an unlikely target. Roosevelt wanted to enter the war, but he wanted to attack Germany, whom he considered to be the bigger threat. In fact, he had ordered the attack on any U-Boats found in the west side of the Atlantic. So, technically the US was already in the war…most people just didn’t know that. Still, the attack on Pearl Harbor was horrific and the United States had to retaliate.

The attack on Pearl Harbor took so many people by surprise. It was a Sunday morning, and many of the military personnel were off base attending church services. The Japanese knew that the ships, planes, and the base in general would be seriously understaffed at the time of the attack. Of course, on the flip side, the fact that so many of the military personnel were away from the base at the time of the attack, meant that the base was able to get back up and running quickly and when we did enter the war, the Japanese were surprised about the attacks coming back at them. Of course, as we all know, the Allies went on to win the war against the Axis nation, including Germany and Japan. It’s been said that people shouldn’t wake the sleeping giant, and that is a wise statement. The Japanese awakened the United States to the fact that appeasing your enemies will not prevent an attack. It takes a show of military might to inform our enemies that it is wise to back away and let the sleeping giants lie.

Of course, the victory that was won following the attack of Pearl Harbor and the US entrance into World War II, came at a high price. A total of 2,403 people (both civilians and soldiers), not to mention ships, airplanes, and

other military equipment. After the attack, the people of the United States were…angry!! We quickly geared up and the war was on for the United States. Our delay could never bring back the people we lost, but we would certainly avenge their loss. Today we remember those we lost, and those who went out to take up the fight to protect our country from such a horrendous attack.

other military equipment. After the attack, the people of the United States were…angry!! We quickly geared up and the war was on for the United States. Our delay could never bring back the people we lost, but we would certainly avenge their loss. Today we remember those we lost, and those who went out to take up the fight to protect our country from such a horrendous attack.

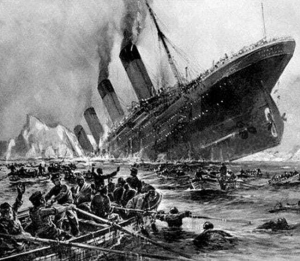

The radioman had done his best. He tried to warn the radioman on RMS Titanic about the dangers lurking in the dark, moonless night…icebergs. Mistakenly believing that Titanic was unsinkable, 25-year-old John George “Jack” Phillips, a British sailor and the senior wireless operator aboard the Titanic during her ill-fated maiden voyage in April 1912, was too busy to listen or heed the warnings. So, the radioman on SS Mesaba turned off his radio and went to bed, making the ship unaware of the disaster the Titanic was experiencing after she hit an iceberg and began to sink. Many rules of the sea changed after that, and from then on, the radio had to be monitored 24/7…in case a disaster happened again. Sadly, safety laws come after disasters.

The radioman had done his best. He tried to warn the radioman on RMS Titanic about the dangers lurking in the dark, moonless night…icebergs. Mistakenly believing that Titanic was unsinkable, 25-year-old John George “Jack” Phillips, a British sailor and the senior wireless operator aboard the Titanic during her ill-fated maiden voyage in April 1912, was too busy to listen or heed the warnings. So, the radioman on SS Mesaba turned off his radio and went to bed, making the ship unaware of the disaster the Titanic was experiencing after she hit an iceberg and began to sink. Many rules of the sea changed after that, and from then on, the radio had to be monitored 24/7…in case a disaster happened again. Sadly, safety laws come after disasters.

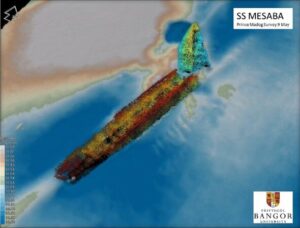

So, what happened to the ship that tried to save the Titanic? I had never given that any thought, but now, more than 110 years after the Titanic sank after striking an iceberg, I read that SS Mesaba, the ship that sent warnings to the famous vessel has also been discovered on the ocean floor. Of course, this was not a surprise to those who found the ship, because they knew what had happened to the ship. Those who knew…researchers at Bournemouth University and Bangor University in Wales, sent a team, using multibeam sonar to find the now famed “ship that tried” to save Titanic.

What I didn’t know, until now, was that just six years after the sinking of RMS Titanic, the SS Mesaba was sunk in the Irish Sea during World War I. Mesaba was making a convoy voyage from Liverpool to Philadelphia on September 1, 1918, when a German U-boat’s torpedo took out the merchant ship, killing twenty people. Titanic was finally found in 1985, but the “ship that tried” to save her, took more than 100 years to locate. Possibly it was because of all the new technology we have, including sonar, which “uses sound waves to measure the distance between a sound source and various objects in its surroundings. This kind of method can be used for navigation, communication, and mapping. It is also frequently used by underwater vessels.” The Bangor researchers used active sonar to map the seabed, and also identified the Mesaba wreckage by emitting pulses of sounds and listening for echoes. Innes McCartney, who is a researcher with Bangor, says the multibeam sonar is a “game-changer” for marine technology. Finally, SS Mesaba’s final resting place is known, although

that doesn’t change anything for the ship. After all these years of wondering, the ship will stay right where it is, although it may be explored now and any valuables can be removed by the team, who was the first to locate, and is therefore eligible to salvage if they choose to.

that doesn’t change anything for the ship. After all these years of wondering, the ship will stay right where it is, although it may be explored now and any valuables can be removed by the team, who was the first to locate, and is therefore eligible to salvage if they choose to.

When a nation has a weapon that is so deadly to its enemy nations, those nations have no choice but to find a new way to beat that weapon. The German U-Boat was just such a weapon. Gliding along silently beneath the sea, the U-Boat put the ships of the Allied nations in constant and grave danger. That was one of the reasons that the British developed a fixation on their presence at sea. They depended on seaborne trade, and during World War I, the Germans were terrorizing that trade.

When a nation has a weapon that is so deadly to its enemy nations, those nations have no choice but to find a new way to beat that weapon. The German U-Boat was just such a weapon. Gliding along silently beneath the sea, the U-Boat put the ships of the Allied nations in constant and grave danger. That was one of the reasons that the British developed a fixation on their presence at sea. They depended on seaborne trade, and during World War I, the Germans were terrorizing that trade.

For much of Great Britain’s history, they enjoyed the luxury of having more battleships than the next two powers combined. For that reason, the Germans knew that they would have to concentrate their efforts on attacking vulnerable shipping lanes to disrupt the British war effort. They didn’t care if there were passengers on those ships. They didn’t care about loss of life or supplies. They had one plan…to dominate the seas. German submarines became a menace to the merchant navy. Something had to change, so the British came up with a plan to counter the U-boat threat. The plan involved disguising armed vessels as harmless trawlers to  lure the submarines in and then wipe them out. The answer to the U-boat were disguised vessels…decoys, known as Q-ships.

lure the submarines in and then wipe them out. The answer to the U-boat were disguised vessels…decoys, known as Q-ships.

Knowing that the U-Boats were under orders to attack just about anything. The Q-ships hid naval guns behind pivoting panels. It was the Sun Tzu tenet of “hold out baits to entice the enemy.” The Q-ships pretended to be disabled and when the U-Boats show up for the kill, the Q-ships went into action. Guns and additional crew had been concealed by hinges that could be dropped at a moment’s notice. The U-boats of World War I had limited range and carrying capacity, so the captains were nervous about wasting their torpedoes. Also, while the U-Boats of World War II were more capable of lang periods of time submerged, the U-Boats of World War I, had limited capability, so they preferred to use the submarine’s main gun to subdue ships whenever possible.

As the U-Boats came into sight of the Q-ship, the Q-ship’s crew would pretend to panic and abandon the ship to  draw the submarine in close. The U-Boats, once lured in, were at the mercy of the Q-ships. The Q-ships began to drop their depth charges as soon as the submarine tried to escape. It was a dangerous game to play and required a brave crew to pull off the ruse, and it was not always successful. Some Q-ships were lost, but because of their efforts the threat of submarines in World War I were lessened. The plan was to try the tactic again in World War II, but ships were in very short supply. The tactic of using decoy ships was much more limited but was also used by the Germans and Americans. While it wasn’t a major tactical warfare practice during the two wars, it was effective while it was used.

draw the submarine in close. The U-Boats, once lured in, were at the mercy of the Q-ships. The Q-ships began to drop their depth charges as soon as the submarine tried to escape. It was a dangerous game to play and required a brave crew to pull off the ruse, and it was not always successful. Some Q-ships were lost, but because of their efforts the threat of submarines in World War I were lessened. The plan was to try the tactic again in World War II, but ships were in very short supply. The tactic of using decoy ships was much more limited but was also used by the Germans and Americans. While it wasn’t a major tactical warfare practice during the two wars, it was effective while it was used.

In the Battle of Trafalgar, on October 21, 1805, the British Royal Navy took on the combined fleets of the French and Spanish Navies during the War of the Third Coalition (August–December 1805) of the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), and soundly defeated them. As the French and Spanish Navies came into sight, Admiral Horatio Nelson raised one set of signal flags. His orders were simple and direct, “England expects every man to do his duty.” His men knew exactly what he meant and what was expected of them…fight, and if necessary, die for their country!! Without hesitation, Nelson’s ships closed in on and destroyed their enemy. The victory of this battle has been called the greatest naval victory in history, and for the remainder of the century, the British really had control over the oceans and the world. In the years following that victory, the British grew lackadaisical about keeping a strong military force, and 111 years later, that issue would be evident for the British Royal Navy when they went up against the Germans in the Battle of Jutland.

In the Battle of Trafalgar, on October 21, 1805, the British Royal Navy took on the combined fleets of the French and Spanish Navies during the War of the Third Coalition (August–December 1805) of the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), and soundly defeated them. As the French and Spanish Navies came into sight, Admiral Horatio Nelson raised one set of signal flags. His orders were simple and direct, “England expects every man to do his duty.” His men knew exactly what he meant and what was expected of them…fight, and if necessary, die for their country!! Without hesitation, Nelson’s ships closed in on and destroyed their enemy. The victory of this battle has been called the greatest naval victory in history, and for the remainder of the century, the British really had control over the oceans and the world. In the years following that victory, the British grew lackadaisical about keeping a strong military force, and 111 years later, that issue would be evident for the British Royal Navy when they went up against the Germans in the Battle of Jutland.

Apparently not understanding that things were no longer what they used to be, a British naval force commanded by Vice Admiral David Beatty confronted a squadron of German ships, led by Admiral Franz von Hipper, approximately 75 miles off the Danish coast, just before 4:00 on the afternoon of May 31, 1916. In what was later called the greatest naval battle of World War I, the two squadrons opened fire on each other simultaneously, beginning the opening phase of the Battle of Jutland.

Following the Battle of Dogger Bank in January 1915, the German navy knew that they were, at the very least, numerically inferior to the British Royal Navy, so the Germans chose not to engage them in a major battle for more than a year. During that time, they began pursuing a new strategy for their naval warfare…namely, its lethal U-boat submarines. Biding his time, Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer waited until May 1916, when the majority of the British Grand Fleet was anchored far away, at Scapa Flow, off the northern coast of Scotland. Then Sheer, the commander of the German High Seas Fleet, believed the time was right to resume attacks on the British coastline. The unique coding system of the U-boats made it very difficult for the British to know what was coming. Scheer ordered 19 U-boat submarines to position themselves for a raid on the North Sea coastal city of Sunderland while using air reconnaissance crafts to keep an eye on the British fleet’s movement  from Scapa Flow. The first planned raid was scrapped because of bad weather, and Scheer instead ordering his fleet, consisting of 24 battleships, five battle cruisers, 11 light cruisers, and 63 destroyers, to head north, to the Skagerrak, a waterway located between Norway and northern Denmark, off the Jutland Peninsula, where they could attack Allied shipping interests…hoping to punch a hole in the stringent British blockade.

from Scapa Flow. The first planned raid was scrapped because of bad weather, and Scheer instead ordering his fleet, consisting of 24 battleships, five battle cruisers, 11 light cruisers, and 63 destroyers, to head north, to the Skagerrak, a waterway located between Norway and northern Denmark, off the Jutland Peninsula, where they could attack Allied shipping interests…hoping to punch a hole in the stringent British blockade.

Truly, the only thing that saved the British Grand Fleet that night was that unbeknownst to Scheer, a newly created intelligence unit located within an old building of the British Admiralty, known as Room 40, had cracked the German codes and warned the British Grand Fleet’s commander, Admiral John Rushworth Jellicoe, of Scheer’s intentions. So, the night before the planned attack…May 30, 1916, a British fleet of 28 battleships, nine battle cruisers, 34 light cruisers, and 80 destroyers set out from Scapa Flow, bound for positions off the Skagerrak.

Then, on May 31, 1916, at 2:20pm, Beatty, leading a British squadron, spotted Hipper’s warships. The squadrons quickly maneuvered south to get a better position, and shots were fired at about 3:48 that afternoon. They fought for 55 minutes, the British losing two British battle cruisers, Indefatigable and Queen Mary. Over 2,000 sailors lost their lives in the battle. At 4:43pm, Hipper’s squadron was joined by the remainder of the German fleet, commanded by Scheer. The British were out gunned, and Beatty was forced to fight a delaying action for the next hour, until Jellicoe could arrive with the rest of the Grand Fleet.

Once both entire fleets were there, they faced off. It was a huge battle of naval strategy between the four commanders, and particularly between Jellicoe and Scheer. As the fleets continued to engage each other throughout the late evening and the early morning of June 1, Jellicoe maneuvered 96 of the British ships into a V-shape surrounding 59 German ships. Hipper’s flagship, Lutzow, was disabled by 24 direct hits, but was still able to sink the British battle cruiser Invincible, before it sank too. Just after 6:30 on the evening of June 1, Scheer’s fleet executed a previously planned withdrawal under cover of darkness to their base at the German port of Wilhelmshaven, ending the battle and cheating the British of the major win they had envisioned.

The Battle of Jutland…or the Battle of the Skagerrak, as it was known to the Germans, involved a total of 100,000 men aboard 250 ships over the course of 72 hours. The Germans, claimed vistory, and the British had to agree…at first anyway. The German navy lost 11 ships, including a battleship and a battle cruiser, and 3,058 men lost their lives. The British losses were heavier, with 14 ships sunk, including three battle cruisers, and 6,784 lives lost. The only thing that made the British losses seem less was that ten more German ships had suffered heavy damage, and by June 2, 1916, only 10 of the German ships that had been involved in the battle were ready to leave port again. Jellicoe, on the other hand, could have put 23 British ships to sea. On July 4, 1916, Scheer reported to the German high command that further fleet action was not an option, and that  submarine warfare was Germany’s best hope for victory at sea. Despite the missed opportunities and heavy losses, the Battle of Jutland had left British naval superiority on the North Sea intact, but if they had been better prepared, they might have held a place of domination over the Germans then. When a nation decides to sit back and ride on its reputation, rather than continue a practice of a strong military force, that nation can find itself in a tough spot when the enemy attacks. The British could have had a very different outcome, but maybe better aim or the favor of God held the German High Seas Fleet at bay. They made no further attempts to break the Allied blockade or cross the Grand Fleet for the rest of World War I.

submarine warfare was Germany’s best hope for victory at sea. Despite the missed opportunities and heavy losses, the Battle of Jutland had left British naval superiority on the North Sea intact, but if they had been better prepared, they might have held a place of domination over the Germans then. When a nation decides to sit back and ride on its reputation, rather than continue a practice of a strong military force, that nation can find itself in a tough spot when the enemy attacks. The British could have had a very different outcome, but maybe better aim or the favor of God held the German High Seas Fleet at bay. They made no further attempts to break the Allied blockade or cross the Grand Fleet for the rest of World War I.

In 1912, the coal transport ship, Jupiter, was transformed, into the US Navy’s first aircraft carrier. The ship was recommissioned USS Langley (CV-1) and was the first aircraft carrier in history. As aircraft carriers go, we would have laughed about the look of this one. This recreated coal transport ship probably should have just stayed a coal transport, but then we wouldn’t have the aircraft carriers we have today, if Jupiter had not been transformed. It all had to start somewhere.

In 1912, the coal transport ship, Jupiter, was transformed, into the US Navy’s first aircraft carrier. The ship was recommissioned USS Langley (CV-1) and was the first aircraft carrier in history. As aircraft carriers go, we would have laughed about the look of this one. This recreated coal transport ship probably should have just stayed a coal transport, but then we wouldn’t have the aircraft carriers we have today, if Jupiter had not been transformed. It all had to start somewhere.

While USS Langley was the first aircraft carrier made, it was not the first to go down in battle. That “honor” goes to HMS Courageous, on September 17, 1939, only a couple weeks after World War II in Europe began. On that day, German U-boat, U-29, sunk the British aircraft carrier with 2 of the 3 torpedoes fired striking the unfortunate carrier. Courageous went down, taking 519 of her crew with her, thereby becoming the first aircraft carrier ever sunk by a submarine. The US Navy’s first aircraft carrier, the Langley, managed to survive until February 27, 1942, when it was sunk by Japanese warplanes (with a little help from US destroyers), and all of its 32 aircraft are lost.

The USS Langley was originally launched in 1912 as the naval collier (coal transport ship) Jupiter. After World  War I, the Jupiter was converted into the Navy’s first aircraft carrier and rechristened the Langley, after aviation pioneer Samuel Pierpont Langley. Uss Langley was the Navy’s first electrically propelled ship. It was capable of speeds of 15 knots. On October 17, 1922, Lieutenant Virgil C Griffin had the great honor of piloting the first plane, a VE-7-SF, from Langley’s decks. Planes had taken off from ships before, but this was a historic moment. The prestige was short-lived, and after 1937, the Langley lost the forward 40 percent of her flight deck as part of a conversion to seaplane tender, a mobile base for squadrons of patrol bombers.

War I, the Jupiter was converted into the Navy’s first aircraft carrier and rechristened the Langley, after aviation pioneer Samuel Pierpont Langley. Uss Langley was the Navy’s first electrically propelled ship. It was capable of speeds of 15 knots. On October 17, 1922, Lieutenant Virgil C Griffin had the great honor of piloting the first plane, a VE-7-SF, from Langley’s decks. Planes had taken off from ships before, but this was a historic moment. The prestige was short-lived, and after 1937, the Langley lost the forward 40 percent of her flight deck as part of a conversion to seaplane tender, a mobile base for squadrons of patrol bombers.

The Langley was part of the Asiatic Fleet in the Philippines when the Japanese attacked on December 8, 1941. Immediately setting sail for Australia, she arrived on January 1, 1942. On February 22nd, under the command of Robert P McConnell, the Langley, carrying 32 Warhawk fighters, left as part of a convoy to aid the Allies in their battle against the Japanese in the Dutch East Indies. Then, on February 27, the Langley parted company  from the convoy and headed straight for the port at Tjilatjap, Java. About 74 miles south of Java, the carrier met up with two US escort destroyers. Then nine Japanese twin-engine bombers attacked the ship. Although the Langley had requested a fighter escort from Java for cover, none could be spared. She and the escort destroyers were virtually alone. The first two Japanese bomber runs missed their target, as they were flying too high, but the third time around they hit their mark three times. The planes on deck went up in flames. The carrier began to list, and Commander McConnell lost his ability to navigate the ship. In an effort to save his men, McConnell ordered the Langley abandoned, and the escort destroyers were able to take his crew to safety. Of the 300 crewmen, only 16 were lost. The destroyers then sank the Langley before the Japanese were able to capture it. It was necessary that they keep it out of Japanese hands. Better at the bottom of the sea that in the hands of the Japanese.

from the convoy and headed straight for the port at Tjilatjap, Java. About 74 miles south of Java, the carrier met up with two US escort destroyers. Then nine Japanese twin-engine bombers attacked the ship. Although the Langley had requested a fighter escort from Java for cover, none could be spared. She and the escort destroyers were virtually alone. The first two Japanese bomber runs missed their target, as they were flying too high, but the third time around they hit their mark three times. The planes on deck went up in flames. The carrier began to list, and Commander McConnell lost his ability to navigate the ship. In an effort to save his men, McConnell ordered the Langley abandoned, and the escort destroyers were able to take his crew to safety. Of the 300 crewmen, only 16 were lost. The destroyers then sank the Langley before the Japanese were able to capture it. It was necessary that they keep it out of Japanese hands. Better at the bottom of the sea that in the hands of the Japanese.

On January 31, 1917, at the height of World War I, Germany announced that they would renew the use of unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic Ocean. The German torpedo-armed submarines, known as U-Boats, prepared to attack any and all ships operating in the Atlantic, including civilian passenger carriers, which were said to have been sighted in war-zone waters. They were prepared to attack without a second thought, whether they were innocent civilians or not. Unleashing the U-Boats was almost like unleashing terrorists, because the U-Boats were an invisible enemy. Yes, the could be seen, but beneath the surface of the water, they could easily hide in the murky darkness, unleashing their torpedoes to go streaking through the water. The first sign of danger was when the doomed ship watchmen saw the dreaded white streak coming at them through the water. There was no time to take evasive action. The ship could not move that fast, and it could not turn on a dime. They were sitting ducks.

On January 31, 1917, at the height of World War I, Germany announced that they would renew the use of unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic Ocean. The German torpedo-armed submarines, known as U-Boats, prepared to attack any and all ships operating in the Atlantic, including civilian passenger carriers, which were said to have been sighted in war-zone waters. They were prepared to attack without a second thought, whether they were innocent civilians or not. Unleashing the U-Boats was almost like unleashing terrorists, because the U-Boats were an invisible enemy. Yes, the could be seen, but beneath the surface of the water, they could easily hide in the murky darkness, unleashing their torpedoes to go streaking through the water. The first sign of danger was when the doomed ship watchmen saw the dreaded white streak coming at them through the water. There was no time to take evasive action. The ship could not move that fast, and it could not turn on a dime. They were sitting ducks.

The vast majority of people of the United States favored neutrality when it came to World War I. So when the war erupted in 1914, President Woodrow Wilson pledged the stay neutral. The problem was that Britain was one of America’s closest trading partners. That created serious tension between the United States and Germany, when Germany attempted a blockade of the British isles. Several US ships traveling to Britain were damaged or sunk by German mines and, in February 1915, Germany announced unrestricted warfare against all ships, neutral or otherwise, that entered the war zone around Britain. One month later, Germany announced that a German cruiser had sunk the William P. Frye, a private American merchant vessel that was transporting grain to England when it disappeared. President Wilson was outraged, but the German government apologized, calling the attack an unfortunate mistake. That didn’t stop their reign of terror, however. In November they sank an Italian liner without warning, killing 272 people, including 27 Americans. Public opinion concerning the war, and the stand of the United States in it began to change. It was time for the United States to get into World War I.

The Germans were far in advance of other nations when it came to submarines. The U-boat was 214 feet long, carried 35 men and 12 torpedoes, and could travel underwater for two hours at a time. In the first few years of World War I, the U-boats took a terrible toll on Allied shipping. In early May 1915, several New York newspapers had to publish a warning by the German embassy in Washington that Americans traveling on British or Allied ships in war zones did so at their own risk. The announcement was placed on the same page as an advertisement for the imminent sailing of the British-owned Lusitania ocean liner from New York to Liverpool. I’m sure they had hoped that people would heed the warning, but many people boarding the Lusitania either didn’t take notice of the warning or they didn’t see it. On May 7, the Lusitania was torpedoed without warning just off the coast of Ireland. Of the 1,959 passengers, 1,198 were killed, including 128 Americans. The Germans had proven once again that they were ruthless and conniving. Following the sinking of the Lusitania The German government accused the Lusitania was carrying munitions. The US demanded an end to German attacks on unarmed passenger and merchant ships, and full repayment for the loss.

Following the sinking of the Lusitania the German government accused the Lusitania was carrying munitions. The US demanded an end to German attacks on unarmed passenger and merchant ships, and full repayment for the loss. Germany countered with a pledge to see to the safety of passengers before sinking unarmed vessels in August 1915. All that changed by January 1917, when Germany, determined to win its war of attrition against the Allies, announced the resumption of unrestricted warfare. Three days later, the United States broke off diplomatic relations with Germany, who, just hours later sunk the American liner Housatonic. None of the 25 Americans on board were killed and they were picked up by a British steamer.

On February 22, Congress passed a $250 million arms-appropriations bill intended to ready the United States for war. British authorities gave the US ambassador to Britain a copy of what has become known as the “Zimmermann Note,” a coded message from German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann to Count Johann von Bernstorff, the German ambassador to Mexico. In the telegram, intercepted and deciphered by British intelligence, Zimmermann stated that, in the event of war with the United States, Mexico should be asked to  enter the conflict as a German ally. In return, Germany would promise to restore to Mexico the lost territories of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. On March 1, the outraged US State Department published the note and America was galvanized against Germany once and for all. In late March, Germany sank four more US merchant ships. President Wilson appeared before Congress and called for a declaration of war against Germany on April 2nd. On April 4th, the Senate voted 82 to six to declare war against Germany. Two days later, the House of Representatives endorsed the declaration by a vote of 373 to 50 and America formally entered World War I. They were after that invisible enemy, and they were determined to find it and destroy it.

enter the conflict as a German ally. In return, Germany would promise to restore to Mexico the lost territories of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. On March 1, the outraged US State Department published the note and America was galvanized against Germany once and for all. In late March, Germany sank four more US merchant ships. President Wilson appeared before Congress and called for a declaration of war against Germany on April 2nd. On April 4th, the Senate voted 82 to six to declare war against Germany. Two days later, the House of Representatives endorsed the declaration by a vote of 373 to 50 and America formally entered World War I. They were after that invisible enemy, and they were determined to find it and destroy it.

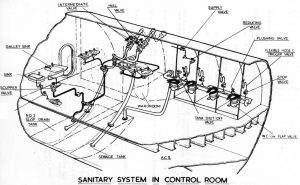

German submarine U-1206 was a Type VIIC U-boat of Nazi Germany’s Kriegsmarine during World War II. Construction started on June 12, 1943 at F. Schichau GmbH in Danzig. She was put into service on March 16, 1944 and a little over a year later, in April 14, 1945 she was at the bottom of the North Sea. The boat’s emblem was a white stork on a black shield with green beak and legs. U-1206 was one of the late-war boats that had been fitted with new deepwater high-pressure toilets, allowing their use while running at depth. These toilets were a rather complicated procedure, so special technicians were trained to operate them. Operating the toilets incorrectly…in the wrong sequence could result in waste or seawater flowing back into the hull. Not only would it have been a nasty mess, it could be dangerous.

German submarine U-1206 was a Type VIIC U-boat of Nazi Germany’s Kriegsmarine during World War II. Construction started on June 12, 1943 at F. Schichau GmbH in Danzig. She was put into service on March 16, 1944 and a little over a year later, in April 14, 1945 she was at the bottom of the North Sea. The boat’s emblem was a white stork on a black shield with green beak and legs. U-1206 was one of the late-war boats that had been fitted with new deepwater high-pressure toilets, allowing their use while running at depth. These toilets were a rather complicated procedure, so special technicians were trained to operate them. Operating the toilets incorrectly…in the wrong sequence could result in waste or seawater flowing back into the hull. Not only would it have been a nasty mess, it could be dangerous.

On April 14, 1945, just 24 days before the end of World War II in Europe, U-1206 was cruising at a depth of 200 feet, eight nautical miles off Peterhead, Scotland. A sailor decided that he knew the procedure for flushing the toilet, and after performing the procedure wrong, caused large amounts of seawater to flood the boat. According to the Commander’s official report, while in the engine room helping to repair one of the diesel engines, he was informed that a malfunction involving the toilet caused a leak in the forward section. The leak flooded the submarine’s batteries, which were located directly beneath toilet, causing them to generate chlorine gas. The Commander had no alternative but to surface. Immediately upon surfacing, basically right in the middle of several British patrol boats, U-1206 was torpedoed, forcing Schlitt to scuttle the submarine. One man died in the attack, three men drowned in the heavy seas after abandoning the vessel and 46 were captured.

I can’t imagine the frustration the Commander must have felt. Prior to the stupidity of one sailor, the submarine had been cruising along in relative safety. A forced surfacing was sure to put them in harms way, but the gas in

the submarine would most certainly kill them too. He did the only thing he could do, and U-1206 was at the bottom of the North Sea less than an hour later, where it would remain, hidden During survey work for the BP Forties Field oil pipeline to Cruden Bay in the mid 1970s, the remains of U-1206 were found at 57°21’N 01°39’W in approximately 230 feet of water.

the submarine would most certainly kill them too. He did the only thing he could do, and U-1206 was at the bottom of the North Sea less than an hour later, where it would remain, hidden During survey work for the BP Forties Field oil pipeline to Cruden Bay in the mid 1970s, the remains of U-1206 were found at 57°21’N 01°39’W in approximately 230 feet of water.

World War II brought with it necessary changes to war ships. Suddenly, the world had planes that could fly greater distances, and even had the ability to land on a ship, provided the ship was big enough to have a relatively short runway. I say relatively short, because the runways on ships seemed like they would be too short to safely land a plane, but they did. One such ship was the HMS Ark Royal.

World War II brought with it necessary changes to war ships. Suddenly, the world had planes that could fly greater distances, and even had the ability to land on a ship, provided the ship was big enough to have a relatively short runway. I say relatively short, because the runways on ships seemed like they would be too short to safely land a plane, but they did. One such ship was the HMS Ark Royal.

The Ark Royal was an English ship designed in 1934 to fit the restrictions of the Washington Naval Treaty. The ship was built by Cammell Laird at Birkenhead, England, and was completed in November 1938. The design of this ship differed from previous aircraft carriers, in that Ark Royal was the first ship on which the hangars and flight deck were an integral part of the hull, instead of an add-on or part of the superstructure. This ship was designed to carry a large number of aircraft. There were two hangar deck levels. HMS Ark Royal served during a period of time during which we first saw the extensive use of naval air power. The Ark Royal played an integral part in developing and refining several carrier tactics.

HNS Ark Royal served in some of the most active naval theatres of the World War II. The ship was involved in the first aerial and U-boat kills of the war, operations off Norway, the search for the German battleship Bismarck, and the Malta Convoys. After Ark Royal survived several near misses, she became known as a “lucky ship” and the reputation stuck…at least until November 13, 1941, when the German submarine U-81 torpedoed her and she sank the following day. Nevertheless, only one of her 1,488 crew members was killed. Her sinking was the subject of several inquiries. While only one man was killed, investigators still couldn’t figure out how the carrier was lost…in spite of efforts to tow her to the naval base at Gibraltar. In the end, they found that several design flaws contributed to the loss. These flaws were rectified in subsequent British carriers. There was, of course, no time to look for the ship then. The war was still going on.

The wreck was discovered in December 2002 by an American underwater survey company using sonar mounted on an autonomous underwater vehicle. The company was under contract from the BBC for the filming of a documentary about the HMS Ark Royal. The ship was at a depth of about 3,300 feet and approximately 30 nautical miles from Gibraltar. So close, and yet so far away.

Anytime a soldier goes to war, there is a possibility of that soldier not returning, but some MOS (Military Occupational Specialty) categories were more dangerous than others. The life expectancy of a ball turret gunner in World War II, for instance, was just 12 minutes…yes, that’s right…12 minutes. And these guys didn’t always have a choice as to what job they did. If they were the shortest, they were most likely going to be a ball turret gunner, because of limited space in the ball. Still, while I don’t know the exact number who died, I know it was quite a few. Of course, soldiers on the ground are more at risk than other occupations too. There were the suicide bombers from Japan, who chose to fly their plane right into a ship too, but I think that few occupations were as deadly as that of the U-Boat crew. It wasn’t so much that the occupation was deadly, but rather that every country in the world was after the German U-Boat.

Anytime a soldier goes to war, there is a possibility of that soldier not returning, but some MOS (Military Occupational Specialty) categories were more dangerous than others. The life expectancy of a ball turret gunner in World War II, for instance, was just 12 minutes…yes, that’s right…12 minutes. And these guys didn’t always have a choice as to what job they did. If they were the shortest, they were most likely going to be a ball turret gunner, because of limited space in the ball. Still, while I don’t know the exact number who died, I know it was quite a few. Of course, soldiers on the ground are more at risk than other occupations too. There were the suicide bombers from Japan, who chose to fly their plane right into a ship too, but I think that few occupations were as deadly as that of the U-Boat crew. It wasn’t so much that the occupation was deadly, but rather that every country in the world was after the German U-Boat.

The U-Boat was a German submarine, and they were the best sumbarine the Germans had. There were 40,000 men who were assigned to the German U-Boats during World War II. Of those assigned to the U-Boats, only 10,000 returned. That is a shocking number!! I would never have wanted the Germans to win World War II, but when I think of the soldiers who fought, I’m sure that there were many who disagreed with Hitler, and others who were brainwashed into following him, but they were still soldiers, and people, and they had been given an assignment that was going to most likely get them killed. You see, the German U-Boat was the most feared of all the ships or submarines during World War II. They had a code system that was hard to crack, and they were sinking the Allies ships. They had to go. Once the Allies figured out their code, they could no longer hide. The U-Boats began dropping like flies, and with them… their crews, of course.

their crews, of course.

The U-Boats ran on battery power when they were submerged, and that didn’t last very long. So they were required to be a surface vessel most of the time, operating on their diesel engines. I don’t think that contributed to the U-Boat becoming a target, because as long as their whereabouts was coded, they were relatively safe. Once that safety net was gone, they were in a lot of trouble, as has been proven by the number of casualties. The fate of the crews of the U-Boats was not a good one, and those 30,000 men paid the final price, once that safety net was gone.

Submarines have been around a long time, but during the world wars, Germany built a submarine that was superior to any other submarine of the time. Called the U-Boat, the name was short for Unterseeboot, or under sea boat. Winston Churchill said, “the only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril.” Churchill identified the threat that the U-Boats posed. The Atlantic Lifeline was vital to Britain’s survival. If Germany had been able to prevent merchant ships from carrying food, raw materials, troops and their equipment from North America to Britain, the outcome of World War II could have been very different. Britain might have been starved into submission, and her armies would not have been equipped with American built tanks and vehicles. The U-Boats were a serious threat. The Battle of the Atlantic was a must win situation. If Germany won that battle, Britain would likely have lost the war.

Submarines have been around a long time, but during the world wars, Germany built a submarine that was superior to any other submarine of the time. Called the U-Boat, the name was short for Unterseeboot, or under sea boat. Winston Churchill said, “the only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril.” Churchill identified the threat that the U-Boats posed. The Atlantic Lifeline was vital to Britain’s survival. If Germany had been able to prevent merchant ships from carrying food, raw materials, troops and their equipment from North America to Britain, the outcome of World War II could have been very different. Britain might have been starved into submission, and her armies would not have been equipped with American built tanks and vehicles. The U-Boats were a serious threat. The Battle of the Atlantic was a must win situation. If Germany won that battle, Britain would likely have lost the war.

From 1918 on, Germany was not supposed to have submarines or submarine crews. However, no checks were in place to stop any research into submarines in Germany and it became clear that during the 1930’s, Germany had been investing time and men into submarine research. Their research and subsequent development of the U-Boat made it a submarine that was very difficult to locate and that made it extremely dangerous. They developed the Enigma machine, which was a series of electro-mechanical rotor cipher machines developed and  used in the early to early-mid twentieth century for commercial and military usage. Enigma was invented by the German engineer Arthur Scherbius at the end of World War I. The codes it could provide were difficult to decipher. German military messages enciphered on the Enigma machine were first broken by the Polish Cipher Bureau, in December 1932. This success was a result of efforts by three Polish cryptologists, Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Rózycki and Henryk Zygalski, working for Polish military intelligence. Rejewski reverse-engineered the device, using theoretical mathematics and material supplied by French military intelligence. Then, the three mathematicians designed mechanical devices for breaking Enigma ciphers, including the cryptologic bomb. In 1938, the Germans made the machine more complex, and increased complexity was repeatedly added to the Enigma machines, making decryption more difficult and requiring further equipment and personnel. It was more than the Poles could readily produce.

used in the early to early-mid twentieth century for commercial and military usage. Enigma was invented by the German engineer Arthur Scherbius at the end of World War I. The codes it could provide were difficult to decipher. German military messages enciphered on the Enigma machine were first broken by the Polish Cipher Bureau, in December 1932. This success was a result of efforts by three Polish cryptologists, Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Rózycki and Henryk Zygalski, working for Polish military intelligence. Rejewski reverse-engineered the device, using theoretical mathematics and material supplied by French military intelligence. Then, the three mathematicians designed mechanical devices for breaking Enigma ciphers, including the cryptologic bomb. In 1938, the Germans made the machine more complex, and increased complexity was repeatedly added to the Enigma machines, making decryption more difficult and requiring further equipment and personnel. It was more than the Poles could readily produce.

Finally there was a breakthrough. The astonishing achievements of the codebreakers of Bletchley Park saved countless lives. At their peak, there were 12,000 codebreakers at Bletchley Park, 8,000 of them women. The codebreakers helped bring victory in North Africa by giving British commander General Montgomery details of  Erwin Rommel’s battle plans and providing the routes of the Nazi supply convoys. This allowed the Royal Navy the opportunity to sink them. Prior to the codebreakers, the U-Boats were only sunk after damage or near damage was done to other ships. Such was the case with the first sinking of a U-Boat. German submarine U-39 was a Type IXA U-boat of the Kriegsmarine that operated from 1938 to the first few days of World War II. On 14 September 1939, just 27 days after she began her first patrol, U-39 attempted to sink the British aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal by firing two torpedoes at her. The torpedoes malfunctioned and exploded just short of the carrier. In retaliation, U-39 was immediately hunted down by three British destroyers. She was disabled with depth charges, and subsequently sunk. All crew members survived and were captured.

Erwin Rommel’s battle plans and providing the routes of the Nazi supply convoys. This allowed the Royal Navy the opportunity to sink them. Prior to the codebreakers, the U-Boats were only sunk after damage or near damage was done to other ships. Such was the case with the first sinking of a U-Boat. German submarine U-39 was a Type IXA U-boat of the Kriegsmarine that operated from 1938 to the first few days of World War II. On 14 September 1939, just 27 days after she began her first patrol, U-39 attempted to sink the British aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal by firing two torpedoes at her. The torpedoes malfunctioned and exploded just short of the carrier. In retaliation, U-39 was immediately hunted down by three British destroyers. She was disabled with depth charges, and subsequently sunk. All crew members survived and were captured.