titanic

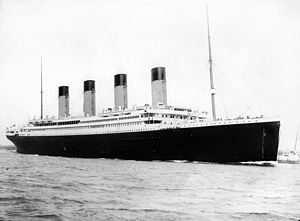

Two years after the sinking of the Titanic, the world was still very aware of the dangers of travel by ship. The Titanic was supposed to be unsinkable, and yet on April 14, 1912, it took more than 1500 people to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean with it. Many safety precautions had changed since Titanic went down. The ship’s radio room had to be manned at all times, crews were trained extensively in emergency procedures, and ships were equipped more than enough lifejackets and lifeboats. Every precaution that they knew to take had been taken, making The Empress of Ireland one of the safest ships on Earth.

Two years after the sinking of the Titanic, the world was still very aware of the dangers of travel by ship. The Titanic was supposed to be unsinkable, and yet on April 14, 1912, it took more than 1500 people to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean with it. Many safety precautions had changed since Titanic went down. The ship’s radio room had to be manned at all times, crews were trained extensively in emergency procedures, and ships were equipped more than enough lifejackets and lifeboats. Every precaution that they knew to take had been taken, making The Empress of Ireland one of the safest ships on Earth.

On May 29, 1914, The Empress of Ireland left Quebec Harbor on a  transatlantic journey to Liverpool England. She was sailing in heavy fog down Canada’s Saint Lawrence River, carrying 1477 passengers and crew. The Norwegian freighter Storstad was also sailing on the Saint Lawrence River on that fateful day. Sailing in heavy fog, without the modern GPS equipment to keep everyone informed of the ships’ positions, is a seriously dangerous undertaking. I don’t know that the normal protocol was for sailing in fog, but it would make sense to me that they should drop anchor and wait for the fog to lift before continuing on. I’m sure that these days, the ships would have some kind of protocol.

transatlantic journey to Liverpool England. She was sailing in heavy fog down Canada’s Saint Lawrence River, carrying 1477 passengers and crew. The Norwegian freighter Storstad was also sailing on the Saint Lawrence River on that fateful day. Sailing in heavy fog, without the modern GPS equipment to keep everyone informed of the ships’ positions, is a seriously dangerous undertaking. I don’t know that the normal protocol was for sailing in fog, but it would make sense to me that they should drop anchor and wait for the fog to lift before continuing on. I’m sure that these days, the ships would have some kind of protocol.

The Empress and the Storstad spotted each other several minutes before the inevitable collision, but altered  courses and confused signals brought them into the fateful moment of impact. I suppose that if each ship hadn’t moved in the same direction, they might have been able to avoid the collision, but unfortunately they did move in the same direction. The Storstad penetrated 15 feet into the Empress of Ireland‘s starboard side, and the vessel sunk within 14 minutes, drowning 1,012 of its passengers and crew in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. It was one of the worst ship disasters in history. Only seven lifeboats escaped the rapidly sinking vessel, but thanks to the efforts of the crew of the Storstad, scores of survivors were pulled out of the icy waters.

courses and confused signals brought them into the fateful moment of impact. I suppose that if each ship hadn’t moved in the same direction, they might have been able to avoid the collision, but unfortunately they did move in the same direction. The Storstad penetrated 15 feet into the Empress of Ireland‘s starboard side, and the vessel sunk within 14 minutes, drowning 1,012 of its passengers and crew in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. It was one of the worst ship disasters in history. Only seven lifeboats escaped the rapidly sinking vessel, but thanks to the efforts of the crew of the Storstad, scores of survivors were pulled out of the icy waters.

Fourteen years before the Titanic sank, Morgan Robertson wrote the novella Futility. It was about the large unsinkable ship “Titan” hitting an iceberg in the Northern Atlantic. Both the Titanic and the fictional Titan did not have enough lifeboats for the thousands of passengers on board. Both were short by about half. While the story behind the sinking of the Titan is somewhat different than the actual events of Titanic, the two are eerily similar, and with so many similarities, one has to wonder how this could have happened. It was like Robertson knew what was coming.

Fourteen years before the Titanic sank, Morgan Robertson wrote the novella Futility. It was about the large unsinkable ship “Titan” hitting an iceberg in the Northern Atlantic. Both the Titanic and the fictional Titan did not have enough lifeboats for the thousands of passengers on board. Both were short by about half. While the story behind the sinking of the Titan is somewhat different than the actual events of Titanic, the two are eerily similar, and with so many similarities, one has to wonder how this could have happened. It was like Robertson knew what was coming.

The story of the Titan puts the “unsinkable” ship sailing through the north Atlantic at breakneck speeds, because as we all know nothing could sink such a ship. Any breech of the holds would immediately close the water-tight doors, stopping the spillover into the other holds. As Titan sailed through the icy waters, they came into an area of fog, and still they did not slow down. Watchmen were posted, one of whom, John Rowland, tended to indulge in drink, since the love of his life left him, and now somehow was on the same ship, and she was married and had a child. While Rowland had been drinking, he was still the one to spot another ship…not that it made a difference. The titan continued full speed ahead, cutting the smaller vessel in half and killing all aboard. The ship still didn’t slow down, and the captain tried to buy the silence of his men, but Rowland would not be bought. As the trip continues, things just get worse. Before long, the ship hits an iceberg, and enough holds are breeched to seal Titan’s doom.

The book, “The Wreck of the Titan,” originally called “Futility,” was so similar to the events of the Titanic, that it was almost eerie, and yet, it was enough different that you knew it was not the same event. It was simply a “fact is stranger than fiction” situation, and no one could possibly have anticipated that a ship with a very similar name, loaded with people and half the necessary lifeboats, would sail at breakneck speeds across the north Atlantic during a time when the icebergs were floating everywhere, just like the ship in the story, and that the ship…Titanic would suffer the same fate as the storybook ship, Titan suffered, fourteen years after the author dreamed up the story in his mind. And yet that is exactly what happened.

The book, “The Wreck of the Titan,” originally called “Futility,” was so similar to the events of the Titanic, that it was almost eerie, and yet, it was enough different that you knew it was not the same event. It was simply a “fact is stranger than fiction” situation, and no one could possibly have anticipated that a ship with a very similar name, loaded with people and half the necessary lifeboats, would sail at breakneck speeds across the north Atlantic during a time when the icebergs were floating everywhere, just like the ship in the story, and that the ship…Titanic would suffer the same fate as the storybook ship, Titan suffered, fourteen years after the author dreamed up the story in his mind. And yet that is exactly what happened.

On April 10, 1912, Titanic set sail from Southampton. Titanic called at Cherbourg in France and Queenstown (now Cobh) in Ireland before heading west to New York. For the passengers and crew, Titanic was the ultimate in luxury, and to be on it was the ultimate thrill. The ship was the most luxurious ship of its day, and to add to their sense of excitement, it was unsinkable. The passengers were assured that the ship had so many fail-safes in place that the builders didn’t even think the lifeboats were necessary, and any that were considered to be in the way, were removed, in what would prove to be a fatal mistake. In the end, there were 20 lifeboats on board the ship, when she was supposed to have 64 lifeboats. Each had a capacity of 65 people. Most lifeboats were lowered to the water with less than half their actual capacity.

On April 10, 1912, Titanic set sail from Southampton. Titanic called at Cherbourg in France and Queenstown (now Cobh) in Ireland before heading west to New York. For the passengers and crew, Titanic was the ultimate in luxury, and to be on it was the ultimate thrill. The ship was the most luxurious ship of its day, and to add to their sense of excitement, it was unsinkable. The passengers were assured that the ship had so many fail-safes in place that the builders didn’t even think the lifeboats were necessary, and any that were considered to be in the way, were removed, in what would prove to be a fatal mistake. In the end, there were 20 lifeboats on board the ship, when she was supposed to have 64 lifeboats. Each had a capacity of 65 people. Most lifeboats were lowered to the water with less than half their actual capacity.

The night of April 14, 1912 was very cold, and the route Titanic was on was littered with icebergs. Other ships  in the area tried to warn Titanic, but the radio operator of Titanic did not take the warnings seriously. He was operating under the mistaken idea that Titanic could sail right through any ice field she might come upon, and have no problems whatsoever. The radio operator was wrong. Nevertheless, he shut of the radio after the 6th warning transmission. The iceberg strike came at 11:40 pm…but the first distress call was sent almost an hour later and even then the ships receiving the calls could did not believe it could be real. Finally, at 12:40 am, Carpathia’s radio operator gave the call to head for Titanic’s last known position.

in the area tried to warn Titanic, but the radio operator of Titanic did not take the warnings seriously. He was operating under the mistaken idea that Titanic could sail right through any ice field she might come upon, and have no problems whatsoever. The radio operator was wrong. Nevertheless, he shut of the radio after the 6th warning transmission. The iceberg strike came at 11:40 pm…but the first distress call was sent almost an hour later and even then the ships receiving the calls could did not believe it could be real. Finally, at 12:40 am, Carpathia’s radio operator gave the call to head for Titanic’s last known position.

Help would come too late for Titanic. By 2:20 am on April 15, 1912, Titanic sank, but she was not without her heroes. As the Titanic was sinking, the deck crew began loading passengers onto lifeboats. The engineering crew stayed at their posts to work the pumps, controlling flooding as much as possible. This action ensured the  power stayed on during the evacuation and allowed the wireless radio system to keep sending distress calls. These men bravely kept at their work and helped save more than 700 people…even though it would cost them their own lives. When Titanic went down, she took with her 1500 people. of those, 688 were crew members, including all 25 of the engineers who worked tirelessly, at their own peril to buy what little bit of time they could for the passengers in their care. Many of the crew members forfeited their lives so that the passengers might live. Were serious mistakes made…yes, of course, but by the same token, the sinking of Titanic saw some of the most amazing bravery ever.

power stayed on during the evacuation and allowed the wireless radio system to keep sending distress calls. These men bravely kept at their work and helped save more than 700 people…even though it would cost them their own lives. When Titanic went down, she took with her 1500 people. of those, 688 were crew members, including all 25 of the engineers who worked tirelessly, at their own peril to buy what little bit of time they could for the passengers in their care. Many of the crew members forfeited their lives so that the passengers might live. Were serious mistakes made…yes, of course, but by the same token, the sinking of Titanic saw some of the most amazing bravery ever.

Travel by ship was not always a safe mode of travel. Things like icebergs, wars, storms, and seashores were known to bring to an end a voyage, that was otherwise very enjoyable. Most people remember the Unsinkable Molly Brown, who was really Margaret Tobin, mostly because of all the publicity and even a musical. Surviving the sinking of the Titanic, while an amazing feat, was something that 705 other people did too. The stories and musical were a way of remembering the tragedy. As amazing as surviving a ship sinking in those days was, there is something that is far more amazing!!

Travel by ship was not always a safe mode of travel. Things like icebergs, wars, storms, and seashores were known to bring to an end a voyage, that was otherwise very enjoyable. Most people remember the Unsinkable Molly Brown, who was really Margaret Tobin, mostly because of all the publicity and even a musical. Surviving the sinking of the Titanic, while an amazing feat, was something that 705 other people did too. The stories and musical were a way of remembering the tragedy. As amazing as surviving a ship sinking in those days was, there is something that is far more amazing!!

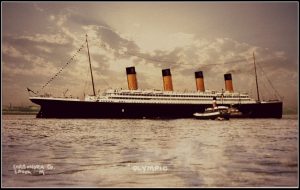

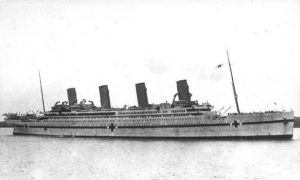

Surviving, not one, but three ship accidents in those days. In 1910, Violet Jessop began working as an ocean liner stewardess and nurse for the White Star line. She was on board when RMS Olympic sailed on September 20, 1911. The Olympic was a luxury ship that was the largest civilian liner at that time. Olympic left from Southampton and collided with the British warship HMS Hawke. There were no fatalities when Olympic sand, and despite damage, the ship was able to make it back to port without sinking. She doesn’t really count this one, because it didn’t sink, but then it did collide with another ship. She didn’t think that one was such an amazing feat, but I’d say that counts. Jessop was then a stewardess on the RMS Titanic April 10, 1912, when she was 24 years old. Four days later, on April 14, it struck an iceberg in the North Atlantic, a story with we all know very well. Titanic sank a little more than two hours after the collision. Jessop described in her memoirs how she was ordered up on deck, because she was to function as an example of how to behave for the non-English speakers who could not follow the instructions given to them. She watched as the crew loaded the lifeboats. She was later ordered into lifeboat 16; and as the boat was being lowered, one of the Titanic’s officers gave her a baby to look after. The next morning, Jessop and the rest of the survivors were rescued by the RMS Carpathia. According to Jessop, while on board the Carpathia, a woman, presumably the baby’s mother, grabbed the baby she was holding and ran off with it without saying a word. Records indicate that the only baby on boat 16 was Assad Thomas, who was handed to Edwina Troutt, and later reunited with his mother on the Carpathia. Then, during the First World War, she served as a stewardess for the British Red Cross. On the morning of November 21, 1916, she was on board the HMHS Britannic, that had been converted into a hospital ship, when it sank in the Aegean Sea due to an unexplained explosion. The Britannic sank within 57 minutes, killing 30 people. British authorities decided that the ship was either struck by a torpedo or hit a mine planted by German forces.

After the war, Jessop continued to work for the White Star Line, before joining the Red Star Line and then the

Royal Mail Line again. During her tenure with Red Star, Jessop went on two around the world cruises on that company’s largest ship, the Belgenland. In her late thirties, Jessop had a brief marriage, and in 1950 she retired to Great Ashfield, Suffolk, where my dad had been stationed during World War II. Jessop, often winkingly called “Miss Unsinkable,” died of congestive heart failure in 1971 at the age of 83.

Royal Mail Line again. During her tenure with Red Star, Jessop went on two around the world cruises on that company’s largest ship, the Belgenland. In her late thirties, Jessop had a brief marriage, and in 1950 she retired to Great Ashfield, Suffolk, where my dad had been stationed during World War II. Jessop, often winkingly called “Miss Unsinkable,” died of congestive heart failure in 1971 at the age of 83.

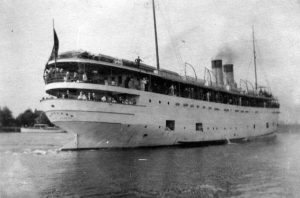

Shipwrecks on the Great Lakes are not a totally uncommon event. Over the last 300 years, Lake Michigan has claimed countless ships, mostly in violent storms and bad weather, especially when the gales of November come in. Nevertheless, a few ships went down without even reaching open waters. One of those ships was the SS Eastland, which went down while docked between LaSalle and Clark Streets on the Chicago River. That site and that ship became the site of the greatest loss of life on the Great Lakes, and it wasn’t a fire, explosion, or act of war, but rather something far more strange.

Shipwrecks on the Great Lakes are not a totally uncommon event. Over the last 300 years, Lake Michigan has claimed countless ships, mostly in violent storms and bad weather, especially when the gales of November come in. Nevertheless, a few ships went down without even reaching open waters. One of those ships was the SS Eastland, which went down while docked between LaSalle and Clark Streets on the Chicago River. That site and that ship became the site of the greatest loss of life on the Great Lakes, and it wasn’t a fire, explosion, or act of war, but rather something far more strange.

The SS Eastland was built by the Michigan Steamship Company in 1902 and began regular passenger service later that year. In July 1903, the ship held an open house so the public could have a look. The sudden number of people, particularly on the upper decks, caused the Eastland to list so severely that water came in through the gangways where passengers and freight would be brought aboard. The ship was obviously top-heavy and this problem had to dealt with quickly, but these incidences continued to plague the ship. In 1905, the Eastland was sold to the Michigan Transportation Company. During the summer of 1906, the Eastland listed again as it transported 2500 passengers, and her carrying capacity was reduced to 2400. But in July 1912, the Eastland was reported as having once more listed to port and then to starboard while carrying passengers. In 1915, the LaFollette Seaman’s Act, which was created as a response to the Titanic not carrying sufficient lifeboats, was passed. The Seaman’s Act mandated that lifeboat space would no longer depend on gross tonnage, but rather on how many passengers were on board. However adding extra weight to the ship put top-heavy vessels like the Eastland at greater risk of listing. In fact, the Senate Commerce Committee was cautioned at the time that placing additional lifeboats and life rafts on the top decks of Great Lakes ships would make them dangerously unstable. This was a warning that the Senate Committee and the Eastland should have heeded.

On July 24, 1915, the Eastland once again fell victim to its top heavy design, and this time the outcome was disastrous. On that cool Saturday morning in Chicago, the Eastland and two other steamers were waiting to take on passengers bound for an annual company picnic in Michigan City, Indiana. For many of the employees of Western Electric Company’s Hawthorne Works, this would be the only holiday they would enjoy all year. A large number of these employees from the 200-acre plant in Cicero, Illinois were Czech Bohemian immigrants. Excitement was in the air as thousands of employees thronged along the river. Three ships would transport them across Lake Michigan to the picnic grounds in Indiana. The Eastland was slated to be the first ship boarded. That morning the Eastland was docked between LaSalle and Clark Streets on the Chicago River. As soon as passengers began boarding, Captain Harry Pedersen and his crew noticed that the ship was listing to port even though most passengers were gathered along the starboard. Attempts were made to right the vessel, but stability seemed uncertain. At 7:10am, the ship reached its maximum carrying capacity of 2572 passengers and the gangplank was pulled in.

As the captain made preparations to depart at 7:21am, the crew continued to let water into the ship’s ballast tanks in an attempt to stabilize the vessel. At 7:23am, water began to pour in through the port gangways. Within minutes, the ship was seriously listing but most passengers seemed unaware of the danger. I wondered how this could have continued to happen, until I saw this video, that explained it very well. By 7:27am, the ship listed so badly that passengers found it too difficult to dance so the orchestra musicians started to play ragtime instead to keep everyone entertained. Just one minute later, at 7:28am, panic set in. Dishes crashed off shelves, a sliding piano almost crushed two passengers, and the band stopped playing as water poured through portholes and gangways. In the next two minutes, the ship completely rolled over on its side, and settled on the shallow river bottom 20 feet below. Passengers below deck now found themselves trapped as water gushed in and heavy furniture careened wildly. Men, women and children threw themselves into the river, but others were trapped between decks, or were crushed by the ship’s furniture and equipment. The lifeboats and life jackets were of no use since the ship had capsized too quickly to access them. In the end, 844 people lost their lives, including 22 entire families. It was a tragedy of epic proportions.

Bystanders on the pier rushed to help those who had been thrown into the river, while a tugboat rescued passengers clinging to the overturned hull of the ship. An eyewitness to the disaster wrote: “I shall never be able to forget what I saw. People were struggling in the water, clustered so thickly that they literally covered

the surface of the river. A few were swimming; the rest were floundering about, some clinging to a life raft that had floated free, others clutching at anything that they could reach…at bits of wood, at each other, grabbing each other, pulling each other down, and screaming! The screaming was the most horrible of them all.” Yes, I’m sure that was the worst, and the loss of life was something that would never be forgotten…especially for an eye witness.

the surface of the river. A few were swimming; the rest were floundering about, some clinging to a life raft that had floated free, others clutching at anything that they could reach…at bits of wood, at each other, grabbing each other, pulling each other down, and screaming! The screaming was the most horrible of them all.” Yes, I’m sure that was the worst, and the loss of life was something that would never be forgotten…especially for an eye witness.

When we think of disasters at sea, Titanic is the first ship that most likely comes to mind, and while Titanic was a terrible tragedy, it was not the worst disaster at sea, by any means. It is amazing to me, however, that some of the others are never talked about at all, and in fact, you may have never heard about them. Titanic had a capacity of 3547 people, but was only carrying 2223 with passengers and crew. The loss of more than 1500 lives, was horrific to be sure, but it was not the worst disaster at sea in history. That distinction goes to The Wilhelm Gustloff.

When we think of disasters at sea, Titanic is the first ship that most likely comes to mind, and while Titanic was a terrible tragedy, it was not the worst disaster at sea, by any means. It is amazing to me, however, that some of the others are never talked about at all, and in fact, you may have never heard about them. Titanic had a capacity of 3547 people, but was only carrying 2223 with passengers and crew. The loss of more than 1500 lives, was horrific to be sure, but it was not the worst disaster at sea in history. That distinction goes to The Wilhelm Gustloff.

The Wilhelm Gustloff was built by the Blohm & Voss shipyards. It measured 684 feet 1 inch long by 77 feet 5 inches wide with a capacity of 25,484 gross register tons. The ship was launched on 5 May 1937. Originally the ship was intended to be named Adolf Hitler, but was named after Wilhelm Gustloff, a leader of the National Socialist Party’s Swiss branch, who had been assassinated by a Jewish medical student in 1936. Hitler decided on the name change after sitting next to Gustloff’s widow during his memorial service. I guess Hitler managed to do a few nice things in his horrid lifetime. The ship was the first purpose-built cruise liner for the German Labour Front or Deutsche Arbeitsfront,  DAF and used by subsidiary organization Kraft durch Freude, KdF meaning Strength Through Joy. The purpose of the ship was to provide recreational and cultural activities for German functionaries and workers, including concerts, cruises, and other holiday trips, and as a public relations tool, to present “a more acceptable image of the Third Reich.” She was the flagship of the KdF cruise fleet, her last civilian role, until the spring of 1939.

DAF and used by subsidiary organization Kraft durch Freude, KdF meaning Strength Through Joy. The purpose of the ship was to provide recreational and cultural activities for German functionaries and workers, including concerts, cruises, and other holiday trips, and as a public relations tool, to present “a more acceptable image of the Third Reich.” She was the flagship of the KdF cruise fleet, her last civilian role, until the spring of 1939.

The Wilhelm Gustloff became a German hospital ship from September 1939 to November 1940, with its official designation being Lazarettschiff. Then, beginning on 20 November 1940, the medical equipment was removed from the ship and she was repainted from the hospital ship colors of white with a green stripe to standard naval grey. As a consequence of the British blockade of the German coastline, she was used as a barracks ship for approximately 1,000 U-boat trainees of the 2nd Submarine Training Division in the port of Gdynia, which had been occupied by Germany and renamed Gotenhafen. The ship was based near Danzig. Then, as things started to go from bad to worse during World War II, the Germans decided that they needed to evacuate as many people as possible from Courland, East Prussia and Danzig, West Prussia. On  January 30, 1945 during Operation Hannibal, which was the naval evacuation of German troops and civilians from Courland, East Prussia, and Danzig, West Prussia as the Soviet Army advanced. The Wilhelm Gustloff’s final voyage was to evacuate German refugees and military personnel as well as technicians who worked at advanced weapon bases in the Baltic from Gdynia, then known to the Germans as Gotenhafen, to Kiel. The ship’s capacity was 1465, but because they were evacuating people, about 9,400 people were onboard. The ship was hit by a torpedo from Soviet submarine S-13 in the Baltic Sea. It quickly sank, taking all 9,400 people with it. The loss of the Wilhelm Gustloff remains the worst disaster at sea in history.

January 30, 1945 during Operation Hannibal, which was the naval evacuation of German troops and civilians from Courland, East Prussia, and Danzig, West Prussia as the Soviet Army advanced. The Wilhelm Gustloff’s final voyage was to evacuate German refugees and military personnel as well as technicians who worked at advanced weapon bases in the Baltic from Gdynia, then known to the Germans as Gotenhafen, to Kiel. The ship’s capacity was 1465, but because they were evacuating people, about 9,400 people were onboard. The ship was hit by a torpedo from Soviet submarine S-13 in the Baltic Sea. It quickly sank, taking all 9,400 people with it. The loss of the Wilhelm Gustloff remains the worst disaster at sea in history.

During World War I, the Germans had taken a hard line concerning the waters around England. It was called unrestricted submarine warfare, and it meant that German submarines would attack any ship found in the war zone, which, in this case, was the area around the British Isles…no matter what kind of ship it was, and even if it was from a neutral country. Of course, this was not going to fly, and since Germany was afraid of the United States, they finally agreed to only go after military ships. Nevertheless, mistakes can be made, and that is what happened on May 7, 1915, when a German U-boat torpedoed and sank the RMS Lusitania, a British ocean liner en route from New York to Liverpool, England. Of the more than 1,900 passengers and crew members on board, more than 1,100 perished, including more than 120 Americans. A warning had been placed in several New York newspapers in early May 1915, by the German Embassy in Washington, DC, stating that Americans traveling on British or Allied ships in war zones did so at their own risk. The announcement was placed on the same page as an advertisement of the imminent sailing of the Lusitania liner from New York back to Liverpool. Still this did not stop the sailing of the Lusitania, because the captain of the Lusitania ignored the British Admiralty’s recommendations, and at 2:12 pm on May 7 the 32,000-ton ship was hit by an exploding torpedo on its starboard side. The torpedo blast was followed by a larger explosion, probably of the ship’s boilers, and the ship sank off the south coast of Ireland in less than 20 minutes.

During World War I, the Germans had taken a hard line concerning the waters around England. It was called unrestricted submarine warfare, and it meant that German submarines would attack any ship found in the war zone, which, in this case, was the area around the British Isles…no matter what kind of ship it was, and even if it was from a neutral country. Of course, this was not going to fly, and since Germany was afraid of the United States, they finally agreed to only go after military ships. Nevertheless, mistakes can be made, and that is what happened on May 7, 1915, when a German U-boat torpedoed and sank the RMS Lusitania, a British ocean liner en route from New York to Liverpool, England. Of the more than 1,900 passengers and crew members on board, more than 1,100 perished, including more than 120 Americans. A warning had been placed in several New York newspapers in early May 1915, by the German Embassy in Washington, DC, stating that Americans traveling on British or Allied ships in war zones did so at their own risk. The announcement was placed on the same page as an advertisement of the imminent sailing of the Lusitania liner from New York back to Liverpool. Still this did not stop the sailing of the Lusitania, because the captain of the Lusitania ignored the British Admiralty’s recommendations, and at 2:12 pm on May 7 the 32,000-ton ship was hit by an exploding torpedo on its starboard side. The torpedo blast was followed by a larger explosion, probably of the ship’s boilers, and the ship sank off the south coast of Ireland in less than 20 minutes.

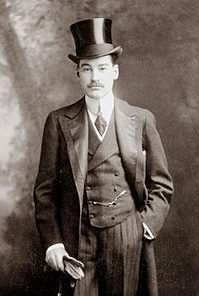

While the sinking of the Lusitania was a horrible tragedy, there were heroics too. One such hero was Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, Sr. Vanderbilt was an extremely wealthy American businessman and sportsman, and a member of the famous Vanderbilt family, but on this trip, he was so much more than that. On May 1, 1915, Alfred Vanderbilt boarded the RMS Lusitania bound for Liverpool as a first class passenger. Vanderbilt was on a business trip. He was traveling with only his valet, Ronald Denyer. His family stayed at home in New York. On May 7, off the coast of County Cork, Ireland, German U-boat, U-20 torpedoed the ship, triggering a secondary explosion that sank the giant ocean liner within 18 minutes. Vanderbilt and Denyer immediately went into action, helping others into lifeboats, and then Vanderbilt gave his lifejacket to save a female passenger. Vanderbilt had promised the young mother of a small baby that he would locate an extra life vest for her. Failing to do so, he offered her his own life vest, which he proceeded to tie on to her himself, because she was holding her infant child in her arms at the time.

Vanderbilt had to know he was sealing his own fate, since he could not swim and he knew there were no other life vests or lifeboats available. They were in waters where no outside help was likely to be coming. Still, he  gave his life for hers and that of her child. Because of his fame, several people on the Lusitania who survived the tragedy were observing him while events unfolded at the time, and so they took note of his actions. I suppose that had he not been famous, people would not have known who he was to tell the story. Vanderbilt and Denyer were among the 1198 passengers who did not survive the incident. His body was never recovered. Probably the most ironic fact is that three years earlier Vanderbilt had made a last-minute decision not to return to the US on RMS Titanic. In fact, his decision not to travel was made so late that some newspaper accounts listed him as a casualty after that sinking too. He would not be so fortunate when he chose to travel on Lusitania.

gave his life for hers and that of her child. Because of his fame, several people on the Lusitania who survived the tragedy were observing him while events unfolded at the time, and so they took note of his actions. I suppose that had he not been famous, people would not have known who he was to tell the story. Vanderbilt and Denyer were among the 1198 passengers who did not survive the incident. His body was never recovered. Probably the most ironic fact is that three years earlier Vanderbilt had made a last-minute decision not to return to the US on RMS Titanic. In fact, his decision not to travel was made so late that some newspaper accounts listed him as a casualty after that sinking too. He would not be so fortunate when he chose to travel on Lusitania.

On this, the 105 anniversary of the April 10, 1912 sailing of the RMS Titanic, for her maiden and only voyage, my thoughts have been leaning toward the people who were on board, and particularly those who did not survive that fateful trip. The Titanic was the most amazing ship of it’s time, filled with luxuries beyond the imagination…at least in first class. Back then, people were separated into classes based on their social importance. It’s sad to think about that, because every person has value, and many of those in 3rd class, or steerage were considered expendable. Nevertheless, it was not just those in steerage who lost their lives when Titanic went down on April 12th, 1912.

On this, the 105 anniversary of the April 10, 1912 sailing of the RMS Titanic, for her maiden and only voyage, my thoughts have been leaning toward the people who were on board, and particularly those who did not survive that fateful trip. The Titanic was the most amazing ship of it’s time, filled with luxuries beyond the imagination…at least in first class. Back then, people were separated into classes based on their social importance. It’s sad to think about that, because every person has value, and many of those in 3rd class, or steerage were considered expendable. Nevertheless, it was not just those in steerage who lost their lives when Titanic went down on April 12th, 1912.

As Titanic set sail on April 10th, here was much excitement. Those who were “lucky” enough to have secured passage, were to be envied. Of course, the rich and famous had no trouble paying for their passage, but the less fortunate had a different situation, and different accommodations. Many of the steerage passengers had spent their last penny to pay for their passage, and still they considered it money well spent, because they were heading to America for a better life. Little did any of the passengers in all three classes know that in just two days, their beautiful ship would be at the bottom of the ocean, along with many of her passengers and crew. It is here that I began to wonder what they were thinking as the ship sank beneath their feet, into the deep dark  murky depths. I know most of them were just trying to find a way to get onto one of the life boats…of which there were too few by at least half, but did it also become that moment when they thought about what might have been for them…had they not taken this particular trip, on this particular ship. I think that anytime a person finds themselves faced with death, their thoughts turn to family, friends, and what might have been. Most luxury trips taken are for a few reasons…among them the scenery, a long awaited visit, or just the sheer luxury of this particular type of trip. No one really considers what might happen if things go wrong, or at the very least, we try not to think about it. Still, when the moment of emergency arrives, did the passengers of Titanic think that if only they had waited for Titanic’s next trip, they wouldn’t be here today…in this most horrible of situations, with so many others screaming in fear, because they knew they were about to die…unless a miracle happened for them.

murky depths. I know most of them were just trying to find a way to get onto one of the life boats…of which there were too few by at least half, but did it also become that moment when they thought about what might have been for them…had they not taken this particular trip, on this particular ship. I think that anytime a person finds themselves faced with death, their thoughts turn to family, friends, and what might have been. Most luxury trips taken are for a few reasons…among them the scenery, a long awaited visit, or just the sheer luxury of this particular type of trip. No one really considers what might happen if things go wrong, or at the very least, we try not to think about it. Still, when the moment of emergency arrives, did the passengers of Titanic think that if only they had waited for Titanic’s next trip, they wouldn’t be here today…in this most horrible of situations, with so many others screaming in fear, because they knew they were about to die…unless a miracle happened for them.

Titanic was carrying 2,222 people (passengers and crew), when she set sail. Of those people only 706 would receive that miracle. For the rest, this would be the end of their life. Of the 706 survivors, 492 were passengers, and 214 were crew members, a fact that I find rather odd. The class distinctions were closer to expected, with 61% of first class passengers surviving, 42% of second class passengers surviving, and 24% of third class passengers surviving. That is a sad reality of a time when class was everything. I’m sure that all of  these people felt that their lives were a tremendous gift, and I’m sure too that their lives changed in a big way. Still, I wonder about the final thoughts of the 1516 people who died that day. I’m sure they wished they had not taken the trip, and I’m sure that they regretted the fact that their family would be sad. It really doesn’t matter what they were thinking, I guess, because it was too late to change what was…for most of them anyway. For the holder of Ticket number 242154, it appears that it was not to late. The holder of that ticket is unknown, but they were given a full refund for their ticket, and it appears that they did not sail on Titanic. Perhaps, they had their ear to the Lord’s Word, and were told not to sail. Not knowing who this person was, we will never know for sure.

these people felt that their lives were a tremendous gift, and I’m sure too that their lives changed in a big way. Still, I wonder about the final thoughts of the 1516 people who died that day. I’m sure they wished they had not taken the trip, and I’m sure that they regretted the fact that their family would be sad. It really doesn’t matter what they were thinking, I guess, because it was too late to change what was…for most of them anyway. For the holder of Ticket number 242154, it appears that it was not to late. The holder of that ticket is unknown, but they were given a full refund for their ticket, and it appears that they did not sail on Titanic. Perhaps, they had their ear to the Lord’s Word, and were told not to sail. Not knowing who this person was, we will never know for sure.

It’s strange…how often society prefers old money to new money. Maybe these days it’s not as common, but in the late 1800s, it was a little bit more common. That was the world Margaret Tobin grew up in. Who is Margaret Tobin, you might ask. Well, we didn’t really remember her as Margaret Tobin, but rather as Molly Brown…or more likely as The Unsinkable Molly Brown. That’s because on this day April 15, 1912, Molly Brown not only survived the sinking of the Titanic, but she heroically saved other people in the water, and kept the people in the lifeboat calm with her stories of life in the west.

It’s strange…how often society prefers old money to new money. Maybe these days it’s not as common, but in the late 1800s, it was a little bit more common. That was the world Margaret Tobin grew up in. Who is Margaret Tobin, you might ask. Well, we didn’t really remember her as Margaret Tobin, but rather as Molly Brown…or more likely as The Unsinkable Molly Brown. That’s because on this day April 15, 1912, Molly Brown not only survived the sinking of the Titanic, but she heroically saved other people in the water, and kept the people in the lifeboat calm with her stories of life in the west.

Molly was born the daughter of an impoverished ditch-digger. As a teenager, Molly went West to join her brother, who was working in the booming silver mining town of Leadville, Colorado. While there, the manager of a local silver mine, James J Brown, noticed her, and they fell in love. The couple married in 1886, and a short time later, James Brown discovered a large deposit of gold. They quickly became very wealthy. They moved to Denver, and tried unsuccessfully to take what should have been their rightful place in society, but the high society of the time…old money, just weren’t prepared to let these unstart, new money people with little social grooming into their ranks. Apparently Molly was a little too flamboyant for the stuffy, old money high society people. She was a little too much for her husband too, because they soon separated, and with her estranged husband’s financial support, Molly was able to live comfortably…for a time anyway…until most of the money ran out.

Molly left Denver and decided to travel. The Eastern elite, didn’t seem to mind Molly’s flamboyance, and soon accepted her as one of them. Socially prominent eastern families like the Astors and Vanderbilts prized her frank western manners and her thrilling stories of frontier life. It was her friendship with these people that brought her to the Titanic, on that fateful trip, but it was Molly herself and her heroic ways that brought her fame, even though  she obviously wasn’t the only woman who survived the sinking. After the ship hit an iceberg and began to sink, Brown was tossed into a lifeboat. She took command of the little boat and helped rescue a drowning sailor and other victims. To keep spirits up, she regaled the anxious survivors with stories of her life in the Old West. One the newspapers heard of her heroics, she gained national fame. She was dubbed “the unsinkable Mrs. Brown” and she became an international heroine. Before very long though, the money ran out, and she faded into obscurity, dying a woman of modest means in New York City in 1932. It was the Broadway musical that would revive her claim to fame, and change her title to The Unsinkable Molly Brown.

she obviously wasn’t the only woman who survived the sinking. After the ship hit an iceberg and began to sink, Brown was tossed into a lifeboat. She took command of the little boat and helped rescue a drowning sailor and other victims. To keep spirits up, she regaled the anxious survivors with stories of her life in the Old West. One the newspapers heard of her heroics, she gained national fame. She was dubbed “the unsinkable Mrs. Brown” and she became an international heroine. Before very long though, the money ran out, and she faded into obscurity, dying a woman of modest means in New York City in 1932. It was the Broadway musical that would revive her claim to fame, and change her title to The Unsinkable Molly Brown.