telegraph

These days, we expect that our president will be familiar with the internet, texting, Facebook, and many other forms of technological advances, but we think of presidents in our past as having to deal with the ancient “technology” of the past, and we even find ourselves almost giggling when we use the term “technology” when speaking about such presidents as Abraham Lincoln. Nevertheless, Abraham Lincoln was a “techy” president…maybe not in the way we use the term today, but since technology often advances at the speed of light, he was quite advanced for his era.

These days, we expect that our president will be familiar with the internet, texting, Facebook, and many other forms of technological advances, but we think of presidents in our past as having to deal with the ancient “technology” of the past, and we even find ourselves almost giggling when we use the term “technology” when speaking about such presidents as Abraham Lincoln. Nevertheless, Abraham Lincoln was a “techy” president…maybe not in the way we use the term today, but since technology often advances at the speed of light, he was quite advanced for his era.

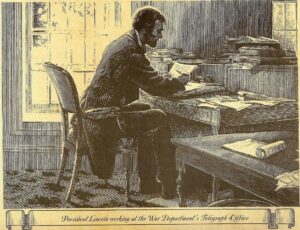

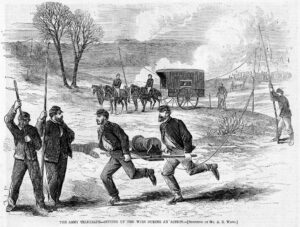

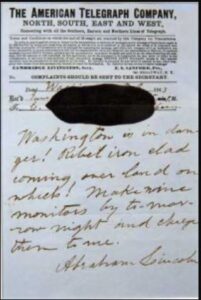

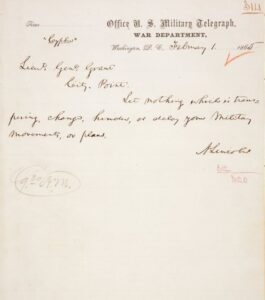

Lincoln had always been a “cutting edge” kind of man, but during the Civil War, his “techy” prowess really came to light. Lincoln was quite taken with the new technology, which he called lightning messages. The federal government had been slow to adopt the telegraph after Samuel Morse’s first successful test message in 1844. Prior to the Civil War, even the federal employees who had to send a telegram from the nation’s capital, had to wait in line with the rest of the public at the city’s central telegraph office. Then, after the outbreak of the Civil  War, the newly created US Military Telegraph Corps undertook the dangerous work of laying more than 15,000 miles of telegraph wire across battlefields, at Lincoln’s orders, so he could transmit news nearly instantaneously from the front lines to the new telegraph office that had been established inside the old library of the War Department building adjacent to the White House in March 1862. He was so interested in the telegraph, in fact, that he sometimes slept on a cot in the telegraph office during major battles. Of course, his main objective was to be able to get information to and from his generals as quickly as possible, but another major objective, that was just as important, was to be out ahead of his Confederate counterpart, Jefferson Davis, who didn’t have the same kind of access. In this way, Lincoln became the first “wired president” nearly 150 years before the advent of texts, tweets, and e-mail, by embracing the original electronic messaging technology…the telegraph.

War, the newly created US Military Telegraph Corps undertook the dangerous work of laying more than 15,000 miles of telegraph wire across battlefields, at Lincoln’s orders, so he could transmit news nearly instantaneously from the front lines to the new telegraph office that had been established inside the old library of the War Department building adjacent to the White House in March 1862. He was so interested in the telegraph, in fact, that he sometimes slept on a cot in the telegraph office during major battles. Of course, his main objective was to be able to get information to and from his generals as quickly as possible, but another major objective, that was just as important, was to be out ahead of his Confederate counterpart, Jefferson Davis, who didn’t have the same kind of access. In this way, Lincoln became the first “wired president” nearly 150 years before the advent of texts, tweets, and e-mail, by embracing the original electronic messaging technology…the telegraph.

President Abraham Lincoln, who was our 16th president, is best remembered for the Gettysburg Address, as well as the Emancipation Proclamation, both of which really stirred the Union, but it was the “techy” side of the man and the nearly 1,000 bite-sized telegrams that he wrote during his presidency, that really helped win the Civil War. It was those telegrams that truly projected presidential power in an unprecedented fashion, for that

time anyway. The fact is that many people tend to be very slow to accept change, especially something as “new-fangled” as the telegraph was at that time in history. It took a man with foresight and wisdom to see that this was a “weapon” of sorts, that would explode our highly divided country into a place where the side of personal rights and personal freedom could propel it into a great nation, instead of two mediocre nations. The person who did that had to be cutting edge!! He had to be ahead of his time…and that is exactly what President Abraham Lincoln was. It is a sad injustice that he was murdered before his full potential could be realized. I wonder where we might have been today, if he had lived out his term.

time anyway. The fact is that many people tend to be very slow to accept change, especially something as “new-fangled” as the telegraph was at that time in history. It took a man with foresight and wisdom to see that this was a “weapon” of sorts, that would explode our highly divided country into a place where the side of personal rights and personal freedom could propel it into a great nation, instead of two mediocre nations. The person who did that had to be cutting edge!! He had to be ahead of his time…and that is exactly what President Abraham Lincoln was. It is a sad injustice that he was murdered before his full potential could be realized. I wonder where we might have been today, if he had lived out his term.

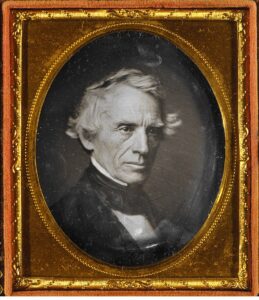

Samuel Finley Breese Morse was born on April 27, 1791, in Charlestown, Massachusetts, the first child of the pastor Jedidiah Morse (1761–1826), who was also a geographer, and his wife Elizabeth Ann Finley Breese (1766–1828). Samuel Morse was an American inventor and painter, having established his reputation as a portrait painter, but it was his work following his first wife’s death that would make his name a household word. Morse married Lucretia Pickering Walker on September 29, 1818, in Concord, New Hampshire. The couple had three children. Susan was born in 1819, Charles was born in 1823, and James was born in 1825. Shortly after giving birth to James, she died of a heart attack on February 7, 1825.

Samuel Finley Breese Morse was born on April 27, 1791, in Charlestown, Massachusetts, the first child of the pastor Jedidiah Morse (1761–1826), who was also a geographer, and his wife Elizabeth Ann Finley Breese (1766–1828). Samuel Morse was an American inventor and painter, having established his reputation as a portrait painter, but it was his work following his first wife’s death that would make his name a household word. Morse married Lucretia Pickering Walker on September 29, 1818, in Concord, New Hampshire. The couple had three children. Susan was born in 1819, Charles was born in 1823, and James was born in 1825. Shortly after giving birth to James, she died of a heart attack on February 7, 1825.

Samuel Morse was away from home, working, when he received a few letters from  his wife, Lucretia. The first letter told him that his wife was ill and the next day, while he was packing to leave, another letter arrived, informing him that she had died. Morse rushed home, but upon his arrival, was informed that she had already been buried. It was devastating, and Morse was greatly upset with the delay in his messages. He was determined to find a better way to transmit messages. Of course, nothing could be done to change the tragic loss of Lucretia, but Morse was determined to make sure this wouldn’t happen to anyone else.

his wife, Lucretia. The first letter told him that his wife was ill and the next day, while he was packing to leave, another letter arrived, informing him that she had died. Morse rushed home, but upon his arrival, was informed that she had already been buried. It was devastating, and Morse was greatly upset with the delay in his messages. He was determined to find a better way to transmit messages. Of course, nothing could be done to change the tragic loss of Lucretia, but Morse was determined to make sure this wouldn’t happen to anyone else.

Following Lucretia’s death, Morse developed Morse code and helped to develop the commercial use of telegraphy in 1833. He also contributed to the invention of a single-wire telegraph system based on European telegraphs. By creating the  telegraph and drafting a series of dots and dashes to communicate via copper wires, 13 years after his wife died, Morse and co-developer, Charles Thomas Jackson successfully created a faster way of communicating and called it Morse Code.

telegraph and drafting a series of dots and dashes to communicate via copper wires, 13 years after his wife died, Morse and co-developer, Charles Thomas Jackson successfully created a faster way of communicating and called it Morse Code.

While Morse code was, without doubt his most important contribution to technology, his life didn’t end there. Morse did eventually find happiness again. He married his second wife, Sarah Elizabeth Griswold on August 10, 1848, in Utica, New York. The couple had four children, Samuel was born 1849, Cornelia was born in 1851, William was born in 1853, and Edward was born in 1857. Samuel Morse died in New York City on April 2, 1872. He was interred at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. By the time of his death, his estate was valued at some $500,000, which would equal about $10.8 million today.

One of the more primitive forms of communication in modern times, was the telegraph. Most of us think of the wild west, and the lone operator sitting in his little office, tapping away on his little telegraph machine. We are also kind of interested in the whole thing, because he was able to write in a language the rest of us do not know, unless we are trained in Morse Code. And most of us think that with modern forms of communication, the telegraph has long been gone from history, but that isn’t so…at least not until January 27, 2006. That was the day when Western Union sent its final telegram. For many, at least for history lovers, that was a sad day. The end of another era. Gone forever.

One of the more primitive forms of communication in modern times, was the telegraph. Most of us think of the wild west, and the lone operator sitting in his little office, tapping away on his little telegraph machine. We are also kind of interested in the whole thing, because he was able to write in a language the rest of us do not know, unless we are trained in Morse Code. And most of us think that with modern forms of communication, the telegraph has long been gone from history, but that isn’t so…at least not until January 27, 2006. That was the day when Western Union sent its final telegram. For many, at least for history lovers, that was a sad day. The end of another era. Gone forever.

While it is a sad day, we must move forward. Technology was rapidly advancing, and we couldn’t drag our feet. In the time it took to prepare a message, go to the telegraph office, take care of the business of payment, have the message sent, and then wait for it to be delivered, we could have made dozens of phone calls of our cell phones. The telegraph was simply a waste of our precious time. So, after 145 years, telegrams were simply gone…no fanfare, no “retirement” party, nothing…just gone. Nothing, but a small announcement on Western Union’s  website prior to the ending. It’s like somehow, such a vital form of communication for 145 years…meant nothing at all.

website prior to the ending. It’s like somehow, such a vital form of communication for 145 years…meant nothing at all.

I’m sure that many people really don’t see why the end of the telegraph was so significant, but for me, there is a nostalgic side to it. I love history, and I am amazed at the innovation of mankind. Over the centuries many amazing inventions have come about, and many discoveries too. Humans really do have a rich history, and when apart of it is over, it is somewhat sad to me. When something that was a mainstay of our society, and just like that, it’s gone, It’s as if we have punished the technology that got us to the place we are. The telegram was just that. For many years, messages from far away…of joy and of sorrow, came to us by telegraph. And in small towns, the person delivering the message knew what it said before the receiver, because he had written it up when it came in.

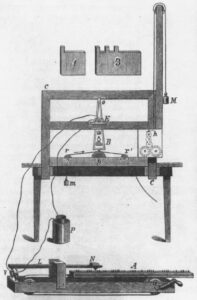

We all know that Samuel Morse invented the telegraph, and then had to sell the idea, before he could get the  money to build what was only a dream in his head before that. Nevertheless, after showing what his machine could do, Samuel Morse was given $30,000 to build his line. The dream became a reality that would continue for 145 years. More than a year later, the first message was sent on May 24, 1844 and the country was convinced. In a partnership with several other men, Morse began the building of more and more lines, expanding the availability of the new-fangled invention. Eventually, they even had field telegraph office. I’m sure it all seemed impossible, but once Morse proved his machine, everyone was on board…at least until the next new thing came alone. That’s typical, but for the telegraph, the next big thing was a ways down the road.

money to build what was only a dream in his head before that. Nevertheless, after showing what his machine could do, Samuel Morse was given $30,000 to build his line. The dream became a reality that would continue for 145 years. More than a year later, the first message was sent on May 24, 1844 and the country was convinced. In a partnership with several other men, Morse began the building of more and more lines, expanding the availability of the new-fangled invention. Eventually, they even had field telegraph office. I’m sure it all seemed impossible, but once Morse proved his machine, everyone was on board…at least until the next new thing came alone. That’s typical, but for the telegraph, the next big thing was a ways down the road.

These days, as wars are fought, we often see, hear, and read the stories written by embedded reporters. It seems almost commonplace, and yet in reality, whenever these reporters go into a war zone, they are risking almost as much as the soldiers. Of course, the reporters don’t go out to attack the enemy, but because of where they are, and who they are with, they make themselves a target to the enemy too. Even as far back as the World Wars, embedded reporters seemed like a common phenomenon, but who would have thought of an embedded reporter as far back as the Indian wars? I certainly didn’t. Nevertheless, journalists were there. One such journalist, who became famous, mostly because he was killed, was Marcus Kellogg, who was traveling with Custer’s 7th Cavalry. Kellogg was a native of Ontario, Canada before immigrating to New York with his family in 1835. As a young man he mastered the art of the telegraph and went to work for the Pacific Telegraphy Company in Wisconsin. During the Civil War, he felt led toward a different calling. He left his career in telegraphy, and became a journalist. Then in 1873, he again felt the calling to change his life, when he decided to move west to the frontier town of Bismarck in Dakota Territory and became the assistant editor of the Bismarck Tribune.

These days, as wars are fought, we often see, hear, and read the stories written by embedded reporters. It seems almost commonplace, and yet in reality, whenever these reporters go into a war zone, they are risking almost as much as the soldiers. Of course, the reporters don’t go out to attack the enemy, but because of where they are, and who they are with, they make themselves a target to the enemy too. Even as far back as the World Wars, embedded reporters seemed like a common phenomenon, but who would have thought of an embedded reporter as far back as the Indian wars? I certainly didn’t. Nevertheless, journalists were there. One such journalist, who became famous, mostly because he was killed, was Marcus Kellogg, who was traveling with Custer’s 7th Cavalry. Kellogg was a native of Ontario, Canada before immigrating to New York with his family in 1835. As a young man he mastered the art of the telegraph and went to work for the Pacific Telegraphy Company in Wisconsin. During the Civil War, he felt led toward a different calling. He left his career in telegraphy, and became a journalist. Then in 1873, he again felt the calling to change his life, when he decided to move west to the frontier town of Bismarck in Dakota Territory and became the assistant editor of the Bismarck Tribune.

Then, while returning from a trip to the East, Kellogg happened to be on the same train as George Custer and his wife, Elizabeth. Custer was on his way to Fort Abraham Lincoln, near Bismarck, where he was going to lead the 7th Cavalry in a planned assault on several bands of Indians who had refused to be confined to reservations. There journey was delayed by an unusually heavy winter storm. The train became snowbound. Being the expert that he was, Kellogg improvised a crude telegraph key, connected it to the wires running alongside the track, and sent a message ahead to the fort asking for help. Custer’s brother, Tom, arrived soon after with a sleigh to rescue them. Custer had enjoyed being made famous by the nation’s newspapers during the Civil War, and now, as he prepared for what he hoped would be his greatest victory ever, Custer wanted to make sure his glorious deeds would be adequately covered in the press. Initially, Custer had planned to take his old friend Clement Lounsberry, who was Kellogg’s employer at the Tribune, with him into the field with the 7th Cavalry, but after meeting Kellogg, he chose him to go instead, mostly because Custer had been impressed by his resourcefulness with a telegraph key.

That one chance event in the winter of 1876, took Kellogg in an unexpected direction…toward the Little Big Horn. When Custer led his soldiers out of Fort Abraham Lincoln and headed west for Montana on May 31, Kellogg rode with him. During the next few weeks, Kellogg filed three dispatches from the field to the Bismarck Tribune, which in turn passed the stories on to the New York Herald. Wanting to make sure the word got out, Custer also sent three anonymous reports on his progress to the Herald. Kellogg’s first dispatches, dated May 31 and June 12, recorded the progress of the expedition westward. His final report, dated June 21, came from the army’s camp along the Rosebud River in southern Montana, not far from the Little Big Horn River. “We leave the Rosebud tomorrow,” Kellogg wrote, “and by the time this reaches you we will have met and fought the red devils, with what result remains to be seen.” The results, of course, were disastrous. Four days later, Sioux and Cheyenne warriors wiped out Custer and his men along the Little Big Horn River. Kellogg was the only journalist to witness the final moments of Custer’s 7th Cavalry. Had he been able to file a story he would have become a national celebrity, but Kellogg did not live to tell the tale, he died alongside Custer’s soldiers.

On July 6, the Bismarck Tribune printed a special extra edition with a top headline reading: “Massacred: Gen. Custer and 261 Men the Victims.” Further down in the column, in substantially smaller type, a sub-headline reported: “The Bismarck Tribune’s Special Correspondent Slain.” The article went on to report, “The body of Kellogg alone remained unstripped of its clothing, and was not mutilated.” The reporter speculated that this

might have been a result of the Indian’s “respect for this humble shover of the lead pencil.” I doubt that the Sioux and Cheyenne respected Kellogg for his journalistic abilities, but his death in one of the most notorious events in the nation’s history made him something of an martyr among newspapermen. The New York Herald later erected a monument to Kellogg over the supposed site of his grave on the Little Big Horn battlefield. Being an embedded journalist might be exciting, but it’s quite risky too.

might have been a result of the Indian’s “respect for this humble shover of the lead pencil.” I doubt that the Sioux and Cheyenne respected Kellogg for his journalistic abilities, but his death in one of the most notorious events in the nation’s history made him something of an martyr among newspapermen. The New York Herald later erected a monument to Kellogg over the supposed site of his grave on the Little Big Horn battlefield. Being an embedded journalist might be exciting, but it’s quite risky too.

Many people today believe that we, as a people, spend far too much time online, on the phone, and otherwise technologically engaged. They believe that the world would be better off without all the technology. I think they have not given enough thought to their idea. We can say. “Let’s get rid of the internet”, but then we would lose the ability to run most businesses. We can say, “Let’s get rid of the telephone”, but again most businesses rely on the phone. Yes, things like television, the internet, radio, and even cell phones are a source of entertainment, but that is not all they are. They keep us informed with important news and weather warnings. They keep us in touch with loved ones, they allow us to place orders for supplies to be brought to our stores, they allow us to provide care for our loved ones who are ill, and to be available to them and to nursing staff at the drop of a hat. So, let’s really explore what it might be like if all technology was gone.

Many people today believe that we, as a people, spend far too much time online, on the phone, and otherwise technologically engaged. They believe that the world would be better off without all the technology. I think they have not given enough thought to their idea. We can say. “Let’s get rid of the internet”, but then we would lose the ability to run most businesses. We can say, “Let’s get rid of the telephone”, but again most businesses rely on the phone. Yes, things like television, the internet, radio, and even cell phones are a source of entertainment, but that is not all they are. They keep us informed with important news and weather warnings. They keep us in touch with loved ones, they allow us to place orders for supplies to be brought to our stores, they allow us to provide care for our loved ones who are ill, and to be available to them and to nursing staff at the drop of a hat. So, let’s really explore what it might be like if all technology was gone.

On September 1, 1859, amateur astronomer Richard Carrington went up into his private observatory, which was attached to his country estate outside London. After cranking open the dome’s shutter to reveal the clear blue sky, he pointed his brass telescope toward the sun and began to sketch a cluster of enormous dark spots that freckled its surface. Remember that he couldn’t look online for pictures of what he was seeing, nor could he look online for an explanation of it. Nevertheless, he would soon know more about what he saw than he would ever have wanted to know. Suddenly, Carrington spotted what he described as “two patches of intensely bright and white light” erupting from the sunspots. Five minutes later the fireballs vanished, but within hours their impact would be felt across the globe.

There was not a lot of technology in existence when the largest solar storm on record, dubbed The Carrington Event occurred, but by that evening the ensuing anomaly would be know worldwide. It was not technology that would bring the world to a standstill…but rather the lack of technology. At that time, the greatest form of technology the world had was the telegraph. Other than letters, it was the world’s communication. And now it was gone. Sparks flew from the machines, and caught paper on fire that happened to be nearby. All over the planet, colorful auroras illuminated the nighttime skies, glowing so brightly that birds began to chirp and laborers started their daily chores, believing the sun had begun rising. Some thought the end of the world was upon them. In reality, it was a very large solar storm, and it could happen again. In fact, the Earth has had several close calls in 2012, 2013, and 2014. If one of these solar storms had made a direct hit on the Earth, electrical transformers would have burst into flames, power grids would have gone down and much of our technology would have been fried. Life as we know it would cease to exist…and we would be in that state for quite some time. Earth would be instantly plunged into the dark ages. These kinds of solar storms have hit the Earth many times before, and experts tell us that it will happen again someday.

I realize that many people disagree with my views on technology, and by the way I believe it is vital, including Facebook. Nevertheless, it really is impossible to have some technology without having the social media. People are just naturally inventive. It you invent one thing, someone will invent another. So the next time you decide that we should just get rid of technology, think about what it has done for the medical world, the information highway, and national security. And if that doesn’t make you change your mind, imagine not being

able to fill up your car, and the fact that it wouldn’t run if you did. Imagine having no electricity, and no way to get the fuel to run a generator. Yes, there are people who are preparing for just such an event, but there really is no way to prepare for all that would be needed if every system known to man was fried. I believe that instead of doing away with technology, we each need to decide how much time we want to spend on things like Facebook, cell phone games, and television, and stick to our decisions. That part really is up to you.

able to fill up your car, and the fact that it wouldn’t run if you did. Imagine having no electricity, and no way to get the fuel to run a generator. Yes, there are people who are preparing for just such an event, but there really is no way to prepare for all that would be needed if every system known to man was fried. I believe that instead of doing away with technology, we each need to decide how much time we want to spend on things like Facebook, cell phone games, and television, and stick to our decisions. That part really is up to you.

Communications have come a long way over the years. Still, most of us give little thought to how difficult it used to be in the not so distant past. Of course, letters were originally the only form of distant communications, and I suppose that some people, like my Uncle Bill, still think that is the best form of communication there ever was. These days, I would have to agree with them in many ways, but there are times when a letter is not quick enough. When the telegraph was invented in the 1830s and 1840s, it revolutionized communication. No longer did it take months to get an important message to family members. Prior to that time, a loved on might be dead for months before the family found out. I’m sure that in most cases, people still relied on letters for most things, so receiving an unexpected telegraph was probably a little scary.

Communications have come a long way over the years. Still, most of us give little thought to how difficult it used to be in the not so distant past. Of course, letters were originally the only form of distant communications, and I suppose that some people, like my Uncle Bill, still think that is the best form of communication there ever was. These days, I would have to agree with them in many ways, but there are times when a letter is not quick enough. When the telegraph was invented in the 1830s and 1840s, it revolutionized communication. No longer did it take months to get an important message to family members. Prior to that time, a loved on might be dead for months before the family found out. I’m sure that in most cases, people still relied on letters for most things, so receiving an unexpected telegraph was probably a little scary.

While telegraph made communications easier in our own country, trying to get an important message to someone from the homeland…not so much. Not until 1866, that is. Early attempts were made to lay  Transatlantic cable for the telegraph in the late 1850s, but those failed, and the confidence of the people was lost, taking with it investors willing to fork out the funds to undertake the next attempt. The first project began in 1854 and was completed in 1858. The cable functioned for only three weeks, but it was the first such project to yield practical results, so progress was being made. The first official telegram to pass between two continents was a letter of congratulation from Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom to the President of the United States James Buchanan on August 16, 1858. Signal quality quickly declined, slowing transmission to an almost unusable speed. The cable was destroyed the following month when Wildman Whitehouse applied excessive voltage to it while trying to achieve faster operation. The cable’s rapid failure undermined public and investor confidence and delayed efforts to restore a connection. A second attempt was undertaken in 1865 with much better materials, and following some setbacks, a connection was completed and put into service on July 28, 1866. This cable proved more durable.

Transatlantic cable for the telegraph in the late 1850s, but those failed, and the confidence of the people was lost, taking with it investors willing to fork out the funds to undertake the next attempt. The first project began in 1854 and was completed in 1858. The cable functioned for only three weeks, but it was the first such project to yield practical results, so progress was being made. The first official telegram to pass between two continents was a letter of congratulation from Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom to the President of the United States James Buchanan on August 16, 1858. Signal quality quickly declined, slowing transmission to an almost unusable speed. The cable was destroyed the following month when Wildman Whitehouse applied excessive voltage to it while trying to achieve faster operation. The cable’s rapid failure undermined public and investor confidence and delayed efforts to restore a connection. A second attempt was undertaken in 1865 with much better materials, and following some setbacks, a connection was completed and put into service on July 28, 1866. This cable proved more durable.

At that point, telegraph communications with the homeland of our nation’s immigrants became possible. While I’m sure it wasn’t inexpensive to send a telegraph…by the standards of the day, it did give the ability to keep in touch with family back home, and really, that was what it was all about. A letter from New York to England  took ten days…provided nothing happened to the ship it set sail on. And it still had to get from out west, if that was where you lived to the east coast. I don’t think a month was far off on this. But then how good was the mail service in Europe? It could still easily take another several weeks for the letter to arrive. Primitive communications for sure. Of course, very few people use telegraph these days. I believe it can still be used to wire money, but electronic transfers are much faster, and often free, so why use it? That is the funny thing about inventions. They are only good until the next big thing that is invented makes the old ones obsolete. That is what things like the cell phone, the internet, and electronic transfers have done to things like letter writing and telegraph.

took ten days…provided nothing happened to the ship it set sail on. And it still had to get from out west, if that was where you lived to the east coast. I don’t think a month was far off on this. But then how good was the mail service in Europe? It could still easily take another several weeks for the letter to arrive. Primitive communications for sure. Of course, very few people use telegraph these days. I believe it can still be used to wire money, but electronic transfers are much faster, and often free, so why use it? That is the funny thing about inventions. They are only good until the next big thing that is invented makes the old ones obsolete. That is what things like the cell phone, the internet, and electronic transfers have done to things like letter writing and telegraph.

As I was sending out a text today, I began to think about the changes in communication we have had through the years. In the very early years of our nation’s history, when a child married and decided to move West, it sometimes meant that family members never heard from each other again, and if they did, it was hit and miss. I’m sure that there were many broken hearted parents as a result of those moves, and I am equally certain that those moves brought about the changes in communication that we see today.

As I was sending out a text today, I began to think about the changes in communication we have had through the years. In the very early years of our nation’s history, when a child married and decided to move West, it sometimes meant that family members never heard from each other again, and if they did, it was hit and miss. I’m sure that there were many broken hearted parents as a result of those moves, and I am equally certain that those moves brought about the changes in communication that we see today.

First, of course came the Pony Express, which while it greatly improved things, was still pretty slow, and news of family members passing or giving birth arrived quite some time after the fact. Not that anyone would have been able make it back in time, but it would be hard to find out after it is all over. The invention of the telephone greatly improved communication, and I’m sure people found it comforting to be able to hear the voice of their loved ones once again.

Today, with so many forms of communications, as well as ease of travel, we are able to see loved ones so often that we, maybe take it for granted. Even if you can’t be with family members, you can Skype, Video Chat, and Face Time, so not only can you hear their voice, but you can see their face, in real time.

Our modern communication abilities have maybe spoiled us to a degree. We have so many  ways to talk and travel, and yet, I don’t know about you, but one of the main ways we communicate…texting, is probably the least personal. It seems like in our busy world, it is easier to text and then wait for the answer, than to talk on the phone. The main reason for this is that you have to hold the phone to talk, so unless it is a long conversation, or one that should be held in a more personal way, we choose the more impersonal…texting. Many people think we text too, as a way of not being too social, and maybe that is so. It seems like we are becoming more of a solitary people in some ways. Still, texting, like the Pony Express, the postal service, the telegraph, telephone, computer, and cell phone are all ways of keeping in touch.

ways to talk and travel, and yet, I don’t know about you, but one of the main ways we communicate…texting, is probably the least personal. It seems like in our busy world, it is easier to text and then wait for the answer, than to talk on the phone. The main reason for this is that you have to hold the phone to talk, so unless it is a long conversation, or one that should be held in a more personal way, we choose the more impersonal…texting. Many people think we text too, as a way of not being too social, and maybe that is so. It seems like we are becoming more of a solitary people in some ways. Still, texting, like the Pony Express, the postal service, the telegraph, telephone, computer, and cell phone are all ways of keeping in touch.