submarines

In 1959, President Dwight Eisenhower wanted to convince the Soviet Union that capitalism could greatly benefit the country. If accepted, the Soviet Union would for all intents and purposes become “Americanized” and would probably have been better off. Of course, not everyone agreed with that idea. Nevertheless, Eisenhower, in an effort intended to showcase their ideologies, arranged the “American National Exhibition” in Moscow. To head up the project, they sent Vice President Richard Nixon to attend the opening. What started out as a potentially good idea, quickly took a turn for the worse when Nixon and Soviet leader Khrushchev got into an argument over the topic of capitalism versus communism. Trying to prove someone wrong in their belief system is no easy task, and the conversation quickly got so heated that the vice president of Pepsi intervened and offered the Soviet leader a cup of his delicious, sugary beverage…which he drank…and very much liked.

In 1959, President Dwight Eisenhower wanted to convince the Soviet Union that capitalism could greatly benefit the country. If accepted, the Soviet Union would for all intents and purposes become “Americanized” and would probably have been better off. Of course, not everyone agreed with that idea. Nevertheless, Eisenhower, in an effort intended to showcase their ideologies, arranged the “American National Exhibition” in Moscow. To head up the project, they sent Vice President Richard Nixon to attend the opening. What started out as a potentially good idea, quickly took a turn for the worse when Nixon and Soviet leader Khrushchev got into an argument over the topic of capitalism versus communism. Trying to prove someone wrong in their belief system is no easy task, and the conversation quickly got so heated that the vice president of Pepsi intervened and offered the Soviet leader a cup of his delicious, sugary beverage…which he drank…and very much liked.

Most people who try sodas, like them, and most have a favorite soda that they enjoy whenever they get the opportunity. For Khrushchev and the people of the Soviet Union, this drink was very different from anything they had tasted before, and they were quickly hooked. Years later, the people of the Soviet Union wanted to strike a deal that would bring Pepsi products to their country permanently. The biggest problem, when it came to importing Pepsi to the Soviet Union, was that Soviet money was not accepted throughout the world. They would have to find something they could trade if they wanted to make this deal. So, they cleverly decided to buy Pepsi using a universal currency…vodka!

In the late 1980s, as their initial agreement to serve Pepsi in their country was about to expire, Russia wanted to renew the deal. Unfortunately for them, this time, their vodka wasn’t going to be enough to cover the cost. The question became…what now? They now had to decide just exactly how much they were willing to pay for the addiction that Pepsi really is. In a wild deal, and one that would seem insane to most of us, Russia decided that it was worth giving up a military arsenal big enough to stock a whole country. So, in order to make the

deal, the Russians traded Pepsi a fleet of subs and boats for a whole lot of soda. The new agreement included 17 submarines, a cruiser, a frigate, and a destroyer. Now, that is a whole lot of Pepsi’s worth. In fact, it was three billion dollars’ worth of Pepsi. So, with this historical exchange, Pepsi to become the 6th most powerful military in the world…for a moment anyway. Then, they sold the fleet to a Swedish company for scrap recycling, ending the short-lived military strength of Pepsi. To this day, some people call this a rumor.

deal, the Russians traded Pepsi a fleet of subs and boats for a whole lot of soda. The new agreement included 17 submarines, a cruiser, a frigate, and a destroyer. Now, that is a whole lot of Pepsi’s worth. In fact, it was three billion dollars’ worth of Pepsi. So, with this historical exchange, Pepsi to become the 6th most powerful military in the world…for a moment anyway. Then, they sold the fleet to a Swedish company for scrap recycling, ending the short-lived military strength of Pepsi. To this day, some people call this a rumor.

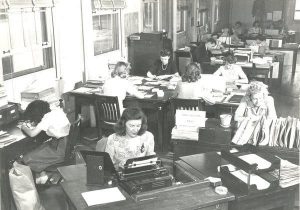

During World War II, when men were in short supply due to deployments, and the secret codes of the Japanese and Germans were causing major problems, the American government was faced with a difficult decision. They needed people who were qualified to break the codes of their enemies, and the only code breakers were in very short supply. The decision was made to search out college-educated women, preferably with degrees in Mathematics, Physics, and those who were fluent in other languages. There weren’t a lot of college educated women in those days, and even fewer with degrees in math or physics, but there were teachers. The Navy and the Army began recruiting these women. The women were required to go through a battery of tests and interviews to see if they had what it took to become code breakers. Many did not, but those who did were offered an exciting, but stressful career.

During World War II, when men were in short supply due to deployments, and the secret codes of the Japanese and Germans were causing major problems, the American government was faced with a difficult decision. They needed people who were qualified to break the codes of their enemies, and the only code breakers were in very short supply. The decision was made to search out college-educated women, preferably with degrees in Mathematics, Physics, and those who were fluent in other languages. There weren’t a lot of college educated women in those days, and even fewer with degrees in math or physics, but there were teachers. The Navy and the Army began recruiting these women. The women were required to go through a battery of tests and interviews to see if they had what it took to become code breakers. Many did not, but those who did were offered an exciting, but stressful career.

Upon arrival in Washington DC, these women found themselves in direct competition with the men, and the men didn’t like it one bit. Nevertheless, the feelings the men had for these women who were a threat to their  job, was at least matched by what the public thought of these women who, sworn to secrecy, had to lie about the work they did. They told people they were secretaries, and glorified waitresses, bring coffee to their bosses, while adding a bit of “interest” to the office. People thought these women were “loose” women…”gold diggers” looking for a husband, and because of the deep need for security, the women were forced to let people think what they wanted too.

job, was at least matched by what the public thought of these women who, sworn to secrecy, had to lie about the work they did. They told people they were secretaries, and glorified waitresses, bring coffee to their bosses, while adding a bit of “interest” to the office. People thought these women were “loose” women…”gold diggers” looking for a husband, and because of the deep need for security, the women were forced to let people think what they wanted too.

No matter what the public thought, these women code breakers were a vital part of the war effort. Our men were dying because we had no idea where the ships and submarines were until they struck. These women turned the tables in favor of the Allies, though few people ever knew it. The women were told they must never speak of what they did there…even after the war, and most of them took their secrets to the grave. While the women were forced to keep their secrets, they all knew that what they were doing mattered. They also knew things about the war, that others didn’t know. They knew the danger the Allied ships were in. They knew about ship that were torpedoed, almost as soon as it happened, and sometimes the ships were ones that friends and loved ones were stationed on…meaning they knew of their loved ones deaths almost immediately after they were killed.

At great sacrifice to themselves, the women code breakers fought a battle in the war that many people never  knew about. The stress, and just the shear gravity of the situation wore of the women. Some later had to seek psychiatric help, and some had nervous breakdowns, still they kept their secrets, lest their services were ever needed again. They kept them in case they ever had to be used again. They kept them because they had orders, and they would follow their orders no matter what. The work had been tedious, and sometimes codes took a long time to crack, but the determined women stuck it out, although most would never be thanked for their hard work. It didn’t matter. Their work was vital, and they were saving lives. That would have to be enough to carry them through the rest of their lives.

knew about. The stress, and just the shear gravity of the situation wore of the women. Some later had to seek psychiatric help, and some had nervous breakdowns, still they kept their secrets, lest their services were ever needed again. They kept them in case they ever had to be used again. They kept them because they had orders, and they would follow their orders no matter what. The work had been tedious, and sometimes codes took a long time to crack, but the determined women stuck it out, although most would never be thanked for their hard work. It didn’t matter. Their work was vital, and they were saving lives. That would have to be enough to carry them through the rest of their lives.

When we think of movie stars, we seldom think of them as soldiers, even if they have played a soldier on television or the movies. Nevertheless, many have served. One of my favorite shows as a kid was McHale’s Navy. McHale was played by Ernest Borgnine, who was born Ermes Effron Borgnino on January 24, 1917, in Hamden, Connecticut. Borgnine was the son of Italian immigrants. His mother, Anna (née Boselli; 1894–c. 1949), was from Carpi, near Modena. His father Camillo Borgnino (1891–1975) was a native of Ottiglio near Alessandria.

When we think of movie stars, we seldom think of them as soldiers, even if they have played a soldier on television or the movies. Nevertheless, many have served. One of my favorite shows as a kid was McHale’s Navy. McHale was played by Ernest Borgnine, who was born Ermes Effron Borgnino on January 24, 1917, in Hamden, Connecticut. Borgnine was the son of Italian immigrants. His mother, Anna (née Boselli; 1894–c. 1949), was from Carpi, near Modena. His father Camillo Borgnino (1891–1975) was a native of Ottiglio near Alessandria.

Borgnine had a normal childhood, and after high school, he enlisted in the United States Navy in October 1935. He served aboard the destroyer/minesweeper USS Lamberton and was honorably discharged from the Navy in October 1941. Then, the  attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1942, changed many things. In January 1942, Borgnine re-enlisted in the Navy. During World War II, he patrolled the Atlantic Coast on an antisubmarine warfare ship, the USS Sylph. In September 1945, he was honorably discharged from the Navy. With the two stints, Borgnine served a total of almost ten years in the Navy and obtained the grade of gunner’s mate 1st class. His military awards include the Navy Good Conduct Medal, American Defense Service Medal with Fleet Clasp, American Campaign Medal with ?3?16″ bronze star, and the World War II Victory Medal. Who knew?

attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1942, changed many things. In January 1942, Borgnine re-enlisted in the Navy. During World War II, he patrolled the Atlantic Coast on an antisubmarine warfare ship, the USS Sylph. In September 1945, he was honorably discharged from the Navy. With the two stints, Borgnine served a total of almost ten years in the Navy and obtained the grade of gunner’s mate 1st class. His military awards include the Navy Good Conduct Medal, American Defense Service Medal with Fleet Clasp, American Campaign Medal with ?3?16″ bronze star, and the World War II Victory Medal. Who knew?

To me, it seems like all this also prepared him for his most famous television show. As a veteran sailor, he knew how things were run on a ship. Of course, how much of his knowledge could be used on the show depends on the directors. If they had any good sense, they would have used his knowledge, and made the show more realistic. Still, as a kid, I doubt if I would know if it was realistic or not, and after all these years, I can’t say I would recall any of the details. Nor would I know if they were realistic or not. Nevertheless, I always liked the show, and I really liked Ernest Borgnine. I just never knew that he had been a sailor during World War II, or that he had played a part in locating and sinking submarines. I also didn’t realize that he enlisted not once, but twice, or that he served a total of ten years. Years later, on July 8, 2012, after many years as a successful actor, Ernest Borgnine died of kidney failure on July 8, 2012 at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, California. He was 95 years old.

To me, it seems like all this also prepared him for his most famous television show. As a veteran sailor, he knew how things were run on a ship. Of course, how much of his knowledge could be used on the show depends on the directors. If they had any good sense, they would have used his knowledge, and made the show more realistic. Still, as a kid, I doubt if I would know if it was realistic or not, and after all these years, I can’t say I would recall any of the details. Nor would I know if they were realistic or not. Nevertheless, I always liked the show, and I really liked Ernest Borgnine. I just never knew that he had been a sailor during World War II, or that he had played a part in locating and sinking submarines. I also didn’t realize that he enlisted not once, but twice, or that he served a total of ten years. Years later, on July 8, 2012, after many years as a successful actor, Ernest Borgnine died of kidney failure on July 8, 2012 at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, California. He was 95 years old.

While Germany was willing to go to war, they had, nevertheless, a healthy fear of the United States. During World War I, Germany introduced unrestricted submarine warfare. It was early 1915, and Germany decided that the area around the British Isles was a war zone, and all merchant ships, including those from neutral countries, would be attacked by the German navy. That action set in motion a series of attacks on merchant ships, that finally led to the sinking of the British passenger ship, RMS Lusitania on May 7, 1915. It was at this point that President Woodrow Wilson decided that it was time to pressure the German government to curb their naval actions. Because the German government didn’t want to antagonize the United States, they agreed to put restrictions on the submarine policy going forward, which angered many of their naval leaders, including the naval commander in chief, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who showed his frustration by resigning in March 1916.

While Germany was willing to go to war, they had, nevertheless, a healthy fear of the United States. During World War I, Germany introduced unrestricted submarine warfare. It was early 1915, and Germany decided that the area around the British Isles was a war zone, and all merchant ships, including those from neutral countries, would be attacked by the German navy. That action set in motion a series of attacks on merchant ships, that finally led to the sinking of the British passenger ship, RMS Lusitania on May 7, 1915. It was at this point that President Woodrow Wilson decided that it was time to pressure the German government to curb their naval actions. Because the German government didn’t want to antagonize the United States, they agreed to put restrictions on the submarine policy going forward, which angered many of their naval leaders, including the naval commander in chief, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who showed his frustration by resigning in March 1916.

On March 24, 1916, soon after Tirpitz’s resignation, a German U-boat submarine attacked the French passenger steamer Sussex, in the English Channel, thinking it was a British ship equipped to lay explosive mines. It was apparently an honest mistake, and the ship did not sink. Still, 50 people were killed and many  more injured, including several Americans. On April 19, in an address to the United States Congress, President Wilson took a firm stance, stating that unless the Imperial German Government agreed to immediately abandon its present methods of warfare against passenger and freight carrying vessels the United States would have no choice but to sever diplomatic relations with the Government of the German Empire altogether.

more injured, including several Americans. On April 19, in an address to the United States Congress, President Wilson took a firm stance, stating that unless the Imperial German Government agreed to immediately abandon its present methods of warfare against passenger and freight carrying vessels the United States would have no choice but to sever diplomatic relations with the Government of the German Empire altogether.

After Wilson’s speech, the US ambassador to Germany, James W. Gerard, spoke directly to Kaiser Wilhelm on May 1 at the German army headquarters at Charleville in eastern France. After Gerard protested the continued German submarine attacks on merchant ships, the Kaiser in turn denounced the American government’s compliance with the Allied naval blockade of Germany, in place since late 1914. Nevertheless, Germany could not risk American entry into the war against them, so when Gerard urged the Kaiser to provide assurances of a change in the submarine policy, the Kaiser agreed.

On May 6, the German government signed the so-called Sussex Pledge, promising to stop the indiscriminate sinking of non-military ships. According to the pledge, merchant ships would be searched, and sunk only if they  were found to be carrying contraband materials. Furthermore, no ship would be sunk before safe passage had been provided for the ship’s crew and its passengers. Gerard was skeptical of the intentions of the Germans, and wrote in a letter to the United States State Department that “German leaders, forced by public opinion, and by the von Tirpitz and Conservative parties would take up ruthless submarine warfare again, possibly in the autumn, but at any rate about February or March, 1917.” Gerard was right, and on February 1, 1917, Germany announced the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare. Two days later, Wilson announced a break in diplomatic relations with the German government, and on April 6, 1917, the United States formally entered World War I on the side of the Allies.

were found to be carrying contraband materials. Furthermore, no ship would be sunk before safe passage had been provided for the ship’s crew and its passengers. Gerard was skeptical of the intentions of the Germans, and wrote in a letter to the United States State Department that “German leaders, forced by public opinion, and by the von Tirpitz and Conservative parties would take up ruthless submarine warfare again, possibly in the autumn, but at any rate about February or March, 1917.” Gerard was right, and on February 1, 1917, Germany announced the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare. Two days later, Wilson announced a break in diplomatic relations with the German government, and on April 6, 1917, the United States formally entered World War I on the side of the Allies.