south pole

Over the centuries, there have been many exploratory expeditions all over the world. Some were privately financed, while others were financed by groups, governments, kings and as in the case of the 1955 to 1958 expedition to Antartica, the Commonwealth of England. The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition (CTAE) was an expedition that successfully completed the first overland crossing of Antarctica, by way of the South Pole. It was also the first expedition to reach the South Pole overland for 46 years. t was preceded only by Amundsen’s expedition and Scott’s expedition in 1911 and 1912. Antartica is a fierce, snow and ice covered, wilderness, which makes me wonder why anyone would want to be on an expedition there. Nevertheless, I suppose that it’s the adventure of it that attracts so many to attempts it.

Over the centuries, there have been many exploratory expeditions all over the world. Some were privately financed, while others were financed by groups, governments, kings and as in the case of the 1955 to 1958 expedition to Antartica, the Commonwealth of England. The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition (CTAE) was an expedition that successfully completed the first overland crossing of Antarctica, by way of the South Pole. It was also the first expedition to reach the South Pole overland for 46 years. t was preceded only by Amundsen’s expedition and Scott’s expedition in 1911 and 1912. Antartica is a fierce, snow and ice covered, wilderness, which makes me wonder why anyone would want to be on an expedition there. Nevertheless, I suppose that it’s the adventure of it that attracts so many to attempts it.

Traditionally, polar expeditions of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration were private ventures, and the CTAE was no exception, even though it was supported by the governments of the United Kingdom, New Zealand, United States, Australia and South Africa, as well as many corporate and individual donations, under the patronage of Queen Elizabeth II. The expedition was headed by British explorer Vivian Fuchs and included New Zealander Sir Edmund Hillary. The group from New Zealand included scientists who were participating in International Geophysical Year research while the British team were separately based at Halley Bay.

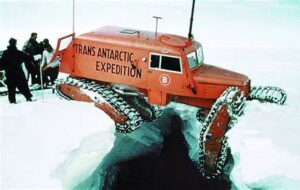

Fuchs took the Danish Polar vessel, Magga Dan and went for additional supplied, returning in December 1956. The southern summer of 1956–1957 was spent consolidating Shackleton Base and establishing the smaller South Ice Base, located about 300 miles inland to the south. The winter of 1957 found Fuchs at Shackleton Base. Then, finally, he set out on the transcontinental journey in November 1957. The twelve-man team traveled in six vehicles, three Sno-Cats, two Weasel tractors, and one specially adapted Muskeg tractor. While they traveled, the team was also tasked with carrying out scientific research including seismic soundings and  gravimetric readings. This was, after all a scientific expedition.

gravimetric readings. This was, after all a scientific expedition.

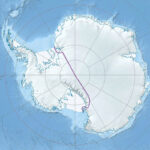

Hillary’s team began setting up Scott Base. This was going to be the final destination for Fuchs. It was located on the opposite side of the continent at McMurdo Sound on the Ross Sea. Using three converted Ferguson TE20 tractors and one Weasel, which had to be abandoned part-way, Hillary and his three men…Ron Balham, Peter Mulgrew, and Murray Ellis…were responsible for route-finding and laying a line of supply depots up the Skelton Glacier and across the Polar Plateau on towards the South Pole, for the use of Fuchs on the final leg of his journey. The remaining member of Hillary’s team carried out geological surveys around the Ross Sea and Victoria Land areas. The Hillary team was not originally supposed to travel as far as the South Pole, but when the supply depots were completed, Hillary saw the opportunity to beat the British and continued south, thereby reaching the Pole…where the US Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station had recently been established by air, on January 3, 1958. While he wasn’t supposed to go, Hillary’s party became the third team to reach the South Pole, preceded by Roald Amundsen in 1911 and Robert Falcon Scott in 1912. Hillary’s arrival also marked the first time that land vehicles had ever reached the Pole. It was a great historic moment.

Fuchs’ team finally reached the Pole from the opposite direction on January 19, 1958, where they met up with Hillary. From there, Fuchs continued overland, following the route that Hillary had forged to get to the South Pole. Then, Hillary flew back to Scott Base in a US plane. He would later rejoin Fuchs by plane for part of the remaining overland journey. The original overland party finally arrived at Scott Base on March 2, 1958, after having completed the historic crossing of 2,158 miles of previously unexplored snow and ice in 99 days. A few days later the expedition members left Antarctica on the on the New Zealand naval ship Endeavour, headed for New Zealand, with Captain Harry Kirkwood at the helm.

Although large quantities of supplies were hauled overland, many forms of resources were used in the expedition. Both parties were also equipped with light aircraft and made extensive use of air support for reconnaissance and supplies. US personnel working in Antartica at the time provided additional logistical help. Both parties also used dog teams for fieldwork trips and backup in case of failure of the mechanical transportation. The dogs were not taken all the way to the Pole. In December 1957 four men from the

expedition flew one of the planes…a de Havilland Canada DHC-3 Otter—on an 11-hour, 1,430-mile, non-stop trans-polar flight across the Antarctic continent from Shackleton Base by way of the Pole to Scott Base, following roughly by air the same route as Fuchs’ overland party. For his accomplishments, Fuchs was knighted. The second overland crossing of the continent did not occur until 1981, during the Transglobe Expedition led by Ranulph Fiennes.

expedition flew one of the planes…a de Havilland Canada DHC-3 Otter—on an 11-hour, 1,430-mile, non-stop trans-polar flight across the Antarctic continent from Shackleton Base by way of the Pole to Scott Base, following roughly by air the same route as Fuchs’ overland party. For his accomplishments, Fuchs was knighted. The second overland crossing of the continent did not occur until 1981, during the Transglobe Expedition led by Ranulph Fiennes.

It’s strange to think that someone would build a ship for the sole purpose of freezing it in the Artic ice sheet as a way of “floating” it over the North Pole, but that was exactly the plan when a ship named Fram (meaning Forward) was designed and built by the Scottish-Norwegian shipwright Colin Archer. The ship was built for Fridtjof Nansen’s 1893 Arctic expedition, to actually freeze it in the polar ice. The ship was a special design to be used in expeditions of the Arctic and Antarctic regions by the Norwegian explorers Fridtjof Nansen, Otto Sverdrup, Oscar Wisting, and Roald Amundsen between 1893 and 1912. Nansen’s ambition was to explore the Arctic farther north than anyone else, but he knew that they would be dealing with a problem that many sailing on the polar ocean had encountered before him, a problem that ended their expeditions…the freezing ice could crush a ship and end the expedition. The ship that was going to survive freezing in the Artic ice sheet, would have to be different…in just about every way. Nansen’s idea was to build a ship that could survive the pressure of the ice, not because it was stronger, but because it’s very shape would let the ice push the ship up, so it would actually “float” on top of the ice.

It’s strange to think that someone would build a ship for the sole purpose of freezing it in the Artic ice sheet as a way of “floating” it over the North Pole, but that was exactly the plan when a ship named Fram (meaning Forward) was designed and built by the Scottish-Norwegian shipwright Colin Archer. The ship was built for Fridtjof Nansen’s 1893 Arctic expedition, to actually freeze it in the polar ice. The ship was a special design to be used in expeditions of the Arctic and Antarctic regions by the Norwegian explorers Fridtjof Nansen, Otto Sverdrup, Oscar Wisting, and Roald Amundsen between 1893 and 1912. Nansen’s ambition was to explore the Arctic farther north than anyone else, but he knew that they would be dealing with a problem that many sailing on the polar ocean had encountered before him, a problem that ended their expeditions…the freezing ice could crush a ship and end the expedition. The ship that was going to survive freezing in the Artic ice sheet, would have to be different…in just about every way. Nansen’s idea was to build a ship that could survive the pressure of the ice, not because it was stronger, but because it’s very shape would let the ice push the ship up, so it would actually “float” on top of the ice.

Fram is a three-masted schooner with a total length of 127 feet 11 inches and width of 36 feet 1 inch. The ship was designed to be both unusually wide and unusually shallow in order to better withstand the forces of pressing ice. By design it would be able to push up through the ice to the top of the ice sheet, thereby allowing  it to float. Fram’s outer layer was made of, which can withstand the ice. It also had almost no keel so it could handle the shallow waters Nansen expected to encounter. The ship was designed with a retractable rudder and propeller, and it was carefully insulated to allow the crew to live on board for up to five years. A windmill was installed to run a generator that would provide electric power for lighting by electric arc lamps. The ship was launched on 26 October 1892. During the initial building process, Fram was fitted with a steam engine, which was fine, until something better came along. Then, before Amundsen’s expedition to the South Pole in 1910, the engine was replaced with a diesel engine, a first for polar exploration vessels.

it to float. Fram’s outer layer was made of, which can withstand the ice. It also had almost no keel so it could handle the shallow waters Nansen expected to encounter. The ship was designed with a retractable rudder and propeller, and it was carefully insulated to allow the crew to live on board for up to five years. A windmill was installed to run a generator that would provide electric power for lighting by electric arc lamps. The ship was launched on 26 October 1892. During the initial building process, Fram was fitted with a steam engine, which was fine, until something better came along. Then, before Amundsen’s expedition to the South Pole in 1910, the engine was replaced with a diesel engine, a first for polar exploration vessels.

Because of wreckage found at Greenland from USS Jeannette, which was lost off Siberia, and driftwood found in the regions of Svalbard and Greenland, Nansen had a theory that an ocean current flowed beneath the Arctic ice sheet from east to west, bringing driftwood from the Siberian region to Svalbard and further west. That was the main reason for building Fram. He wanted to order to explore this theory. His expedition ended up lasting three years, during which time, Nansen realized that Fram would not reach the North Pole directly. The current either wasn’t strong enough, or the polar ice was actually on land at the North Pole. So, he and Hjalmar Johansen set out to reach it on skis. After reaching 86° 14′ north, he had to turn back to spend the winter at Franz Joseph Land. During their expedition, Nansen and Johansen survived on walrus and polar bear meat and blubber. Finally, after they met up with British explorers from the Jackson-Harmsworth Expedition, they arrived back in Norway only days before the Fram also returned there. Their skiing mission was far more successful than the Fram’s mission, as the ship had spent nearly three years trapped in the ice, after only reaching 85° 57′ N. Fram made a scientific expedition to the Canadian Artic Archipelago between 1892 and 1902, and after being fitted with the diesel engine, Amundsen made his South Pole expedition from 1910 to 1912. Fram was

the first ship to reach the South Pole, during which Fram reached 78° 41′ S.

the first ship to reach the South Pole, during which Fram reached 78° 41′ S.

Following these expeditions, Fram was left to decay in storage from 1912 until the late 1920s. Then, Lars Christensen, Otto Sverdrup, and Oscar Wisting decide to begin an effort to preserve it by starting the Fram Committee. Finally, the now restored ship was installed in the Fram Museum in 1945, where it now stands.

Competition is the driving force behind so many accomplishments, especially world records. On January 18, 1912, after a two-month ordeal, the expedition of British explorer Robert Falcon Scott arrived at the South Pole. Scott was a British naval officer, who began his first Antarctic expedition in 1901 aboard the Discovery. Scott spent three years exploring the area and discovered the Edward VII Peninsula, surveyed the coast of Victoria Land…which were both areas of Antarctica on the Ross Sea, and led limited expeditions into the continent itself.

Competition is the driving force behind so many accomplishments, especially world records. On January 18, 1912, after a two-month ordeal, the expedition of British explorer Robert Falcon Scott arrived at the South Pole. Scott was a British naval officer, who began his first Antarctic expedition in 1901 aboard the Discovery. Scott spent three years exploring the area and discovered the Edward VII Peninsula, surveyed the coast of Victoria Land…which were both areas of Antarctica on the Ross Sea, and led limited expeditions into the continent itself.

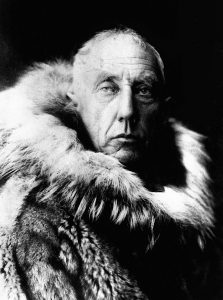

Soon, skirting the fringes of Antarctica was not enough, and others had taken an interest in the area too. So, in 1911, Scott and Norwegian explorer, Roald Amundsen began an “undeclared” race to the South Pole. While it was “undeclared,” it was no less a competition, and both men knew it. Sailing his ship into Antarctica’s Bay of Whales, Amundsen set up base camp 60 miles closer to the pole than Scott. In October, both explorers set off. Amundsen was using sleigh dogs and Scott used Siberian motor sledges, Siberian ponies, and dogs. Scott’s journey was fraught with mishaps. The motor sleds broke down, the ponies had to be shot, and the dog teams were sent back as Scott and four companions continued on foot. Nothing was going according to plan.

Nevertheless, on January 18, 1912, Scott’s group finally reached the pole…only to find that Amundsen had preceded them by over a month. Amundsen’s expedition won the race to the pole on December 14, 1911. Encountering good weather on their return trip, they safely reached their base camp in late January. For Scott,

it was a day of mixed feelings, I’m sure. They made it to the pole, but they came in second. The return trip was not going to be much better, but it had to be made. The weather was exceptionally bad, and two members of the team died on the journey back to their base camp. Scott and the other two survivors were trapped in their tent by a storm, when they were just 11 miles from their base camp. Scott, who kept a journal of the trip, like most explorers did, wrote a final entry in his diary in late March. The frozen bodies of he and his two compatriots were recovered eight months later. It was a sad ending to their horrific trip.

it was a day of mixed feelings, I’m sure. They made it to the pole, but they came in second. The return trip was not going to be much better, but it had to be made. The weather was exceptionally bad, and two members of the team died on the journey back to their base camp. Scott and the other two survivors were trapped in their tent by a storm, when they were just 11 miles from their base camp. Scott, who kept a journal of the trip, like most explorers did, wrote a final entry in his diary in late March. The frozen bodies of he and his two compatriots were recovered eight months later. It was a sad ending to their horrific trip.