south africa

Any illness that takes a life is a tragedy, but sometimes an illness doesn’t take the life, exactly, it just stops everything about that life…in its tracks. In January of 1988 at age 12, Martin Pistorius of South Africa came down with a strange illness. his illness was so unusual, that his doctors weren’t even sure what it was. Nevertheless, they did speculate that it might be Cryptococcal Meningitis. Cryptococcosis is a potentially fatal fungal infection of mainly the lungs, where it presents as a type of pneumonia; and also, the brain, where it appears as a meningitis. The symptoms seem common enough…a cough, difficulty breathing, chest pain, and fever are seen when the lungs are infected. When the brain is infected, symptoms include headache, fever, neck pain, nausea and vomiting, light sensitivity, and confusion or changes in behavior. It can also affect other parts of the body including skin, where it may appear as several fluid-filled nodules with dead tissue.

Any illness that takes a life is a tragedy, but sometimes an illness doesn’t take the life, exactly, it just stops everything about that life…in its tracks. In January of 1988 at age 12, Martin Pistorius of South Africa came down with a strange illness. his illness was so unusual, that his doctors weren’t even sure what it was. Nevertheless, they did speculate that it might be Cryptococcal Meningitis. Cryptococcosis is a potentially fatal fungal infection of mainly the lungs, where it presents as a type of pneumonia; and also, the brain, where it appears as a meningitis. The symptoms seem common enough…a cough, difficulty breathing, chest pain, and fever are seen when the lungs are infected. When the brain is infected, symptoms include headache, fever, neck pain, nausea and vomiting, light sensitivity, and confusion or changes in behavior. It can also affect other parts of the body including skin, where it may appear as several fluid-filled nodules with dead tissue.

As the disease progressed, Pistorius got progressively worse. At first, he lost the ability to move by himself, then his ability to make eye contact, and finally his ability to speak. His parents were told their son was essentially in a vegetative state, basically they were told he was almost brain dead, that he wasn’t “really there” and would die soon. It was the most devastating news a parent could hear, but Pistorius didn’t die. He just stayed in a vegetative state for the next 12 years. His parents couldn’t give up on their son, and so, they took care of him…bathing, dressing, and feeding him. They days turned into years…years of grieving, sadness, weariness, and a sense of having made a mistake, for not “letting him go” sooner. The weariness got so bad that one day, not knowing her son could hear her, Joan Pistorius told him, “I hope you die.” It was a harsh thing to say, but she thought he was brain dead, and she was simply exhausted.

As Joan Pistorius would later find out, to her horror I’m sure, her son heard and understood every word. Somewhere between the ages of 14 and 16, Pistorius had begun to wake up…slowly. At first, it may have been barely noticeable, but at some point, it got to where Pistorius later recalled, “I was aware of everything, just like any normal person.” He could hear, and very much understand and process what he heard, but he couldn’t say or do anything about what he heard or let anyone know that he had heard. The condition Pistorius had, is known as “locked-in syndrome” and can be caused by a stroke, traumatic brain injury, infection, or drug overdose. There is no known cure. I’m sure the situation was even more frustrating for Pistorius, than it was for his mom. Although Pistorius could see, hear, and understand everything, he couldn’t move his body. “Everyone was so used to me not being there that they didn’t notice when I began to be present again,” he later recalled. “The stark reality hit me that I was going to spend the rest of my life like that – totally alone.”

Pistorius made a conscious choice to disengage from his thoughts as his way of coping. Because of his condition, Pistorius spent a lot of time at a care center while his mother worked. He hated the children’s TV show Barney, and that was on constantly there. That show led him to start reengaging with his thoughts in an attempt to take some control of his life. As his thought life improved, so did his body. Then, one glorious day, a relief worker at his daycare center noticed his slight movements and realized Pistorius could communicate. She immediately told his parents, telling them to get another evaluation. Finally, they knew he was conscious. His

recovery wasn’t instantaneous, of course, but by age 26, he could use a computer to communicate. Pistorius later enrolled in college, majoring in computer science and started a company online. It was a long road, but he has come full circle, by 2011 when he published his memoir, “Ghost Boy.” Pistorius met his wife Joanna, who is from England in 2008 through his sister Kim, who had moved to there. After meeting Joanna, he moved to England too, and they were married in 2009. By that time, while still using a wheelchair, he was racing in it. Their son, Sebastian Albert Pistorius, was born a few months later.

recovery wasn’t instantaneous, of course, but by age 26, he could use a computer to communicate. Pistorius later enrolled in college, majoring in computer science and started a company online. It was a long road, but he has come full circle, by 2011 when he published his memoir, “Ghost Boy.” Pistorius met his wife Joanna, who is from England in 2008 through his sister Kim, who had moved to there. After meeting Joanna, he moved to England too, and they were married in 2009. By that time, while still using a wheelchair, he was racing in it. Their son, Sebastian Albert Pistorius, was born a few months later.

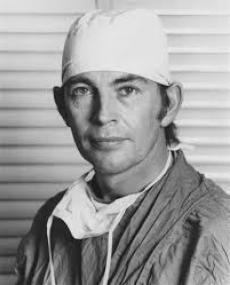

For a heart surgeon, there comes a point with a heart, when the diseased part is bad enough that it can’t be fixed. No matter how hard he tries, it is going to take a miracle to save the owner of that heart. That was the place that Dr Christiaan Neethling Barnard was facing in November 1967. His patient, 54-year-old Louis Washkansky was…well, dying, with little hope of survival. Heart transplants weren’t done every day like they are these days, and Barnard had told Mr and Mrs Washkansky that the operation had an 80% chance of success, an assessment which has been criticized as misleading, but by the same token, Mr Washkansky had no chance of survival without the transplant. Then, the opportunity presented itself, in the form of accident victim, Denise Darvall.

For a heart surgeon, there comes a point with a heart, when the diseased part is bad enough that it can’t be fixed. No matter how hard he tries, it is going to take a miracle to save the owner of that heart. That was the place that Dr Christiaan Neethling Barnard was facing in November 1967. His patient, 54-year-old Louis Washkansky was…well, dying, with little hope of survival. Heart transplants weren’t done every day like they are these days, and Barnard had told Mr and Mrs Washkansky that the operation had an 80% chance of success, an assessment which has been criticized as misleading, but by the same token, Mr Washkansky had no chance of survival without the transplant. Then, the opportunity presented itself, in the form of accident victim, Denise Darvall.

The time had come, and on December 3, 1967, Darvall’s heart was transplanted by Dr Bernard into Washkansky. As with any new procedure, there were the inevitable risks, and while Washkansky regained full consciousness and was able to talk easily with his wife, he developed pneumonia eighteen days later and because of his compromised immune system, due largely to the anti-rejection drugs, he died eighteen days later of pneumonia, largely brought on by the anti-rejection drugs that suppressed his immune system. Dr Bernard could have given up, but he did not. His second heart transplant patient, Philip Blaiberg received his new heart in 1968, and while his life after that was not long, he did live another year and a half. Of course, these days, the heart transplant patient has a much better prognosis because of how much medical procedures have improved.

Born in Beaufort West, Cape Province, South Africa, on November 8, 1922, Bernard studied medicine and practiced for several years in his native South Africa. As a young doctor, he experimented on dogs, which I suppose might make some people angry. Nevertheless, Barnard developed a remedy for the infant defect of intestinal atresia. Intestinal atresia refers to a part of the fetal bowel that is not developed, and the intestinal tract becomes partially or completely blocked (bowel obstruction). His technique saved the lives of ten babies in Cape Town and was adopted by surgeons in Britain and the United States.

In 1955, Bernard decided to travel to the United States to further his studies. He was initially assigned further  gastrointestinal work by Owen Harding Wangensteen at the University of Minnesota. Then, Bernard was introduced to the heart-lung machine, and was allowed to transfer to the service run by open heart surgery pioneer Walt Lillehei. After his study abroad, he returned to South Africa in 1958. Barnard was appointed head of the Department of Experimental Surgery at the Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town. After a long and successful career, Bernard retired as head of the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery in Cape Town in 1983 after rheumatoid arthritis in his hands ended his surgical career. Still, he could not leave surgery completely alone. He became interested in anti-aging research, and in 1986 his reputation suffered when he promoted Glycel, an expensive “anti-aging” skin cream, whose approval was withdrawn by the United States Food and Drug Administration soon thereafter. During his remaining years, he established the Christiaan Barnard Foundation, which was dedicated to helping underprivileged children throughout the world. He died on September 2, 2001 at the age of 78 in Paphos, Cyprus after an asthma attack.

gastrointestinal work by Owen Harding Wangensteen at the University of Minnesota. Then, Bernard was introduced to the heart-lung machine, and was allowed to transfer to the service run by open heart surgery pioneer Walt Lillehei. After his study abroad, he returned to South Africa in 1958. Barnard was appointed head of the Department of Experimental Surgery at the Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town. After a long and successful career, Bernard retired as head of the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery in Cape Town in 1983 after rheumatoid arthritis in his hands ended his surgical career. Still, he could not leave surgery completely alone. He became interested in anti-aging research, and in 1986 his reputation suffered when he promoted Glycel, an expensive “anti-aging” skin cream, whose approval was withdrawn by the United States Food and Drug Administration soon thereafter. During his remaining years, he established the Christiaan Barnard Foundation, which was dedicated to helping underprivileged children throughout the world. He died on September 2, 2001 at the age of 78 in Paphos, Cyprus after an asthma attack.

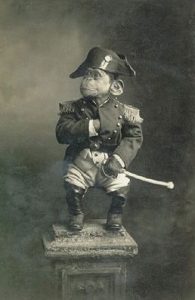

James Edwin Wide had lost both his legs in a work accident years earlier, and so in 1880, when he came across a Chacma Baboon driving an oxcart while visiting a busy South African market, he saw a way to make his life easier. Wide was impressed with the skills, and so he decided to buy him. Having two peg-legs and working had been very difficult on Wide over the years, and finally he saw an end to years of hardship. Impressed by the primate’s skills, Wide bought him, named him Jack, and made him his pet and personal assistant. His original plan was to have Jack drive him on his half-mile commute to the train station. So the first thing he trained the Jack to do was push him to and from work in a small trolley. Soon, Jack was also helping with household chores, sweeping floors and taking out the trash. Jack was very good at his work, and he truly loved Wide, almost as if Wide was his child.

James Edwin Wide had lost both his legs in a work accident years earlier, and so in 1880, when he came across a Chacma Baboon driving an oxcart while visiting a busy South African market, he saw a way to make his life easier. Wide was impressed with the skills, and so he decided to buy him. Having two peg-legs and working had been very difficult on Wide over the years, and finally he saw an end to years of hardship. Impressed by the primate’s skills, Wide bought him, named him Jack, and made him his pet and personal assistant. His original plan was to have Jack drive him on his half-mile commute to the train station. So the first thing he trained the Jack to do was push him to and from work in a small trolley. Soon, Jack was also helping with household chores, sweeping floors and taking out the trash. Jack was very good at his work, and he truly loved Wide, almost as if Wide was his child.

While Jack was very good at his caregiving job, it was at the signal box Jack truly shined. The signal box was a system of manual switches operated in connection with the approaching trains whistles. As trains approached the  rail switches at the Uitenhage train station, they would toot their whistle a specific number of times to alert the signalman which tracks to change. By watching his owner, Jack picked up the pattern and started tugging on the levers himself. Jack was so smart. He was able to totally take over the signalman’s job that had been held by Wide. Soon, Wide was able to kick back and relax as his furry helper did all of the work switching the rails. According to The Railway Signal, Wide “trained the baboon to such perfection that he was able to sit in his cabin stuffing birds, etc, while the animal, which was chained up outside, pulled all the levers and points.”

rail switches at the Uitenhage train station, they would toot their whistle a specific number of times to alert the signalman which tracks to change. By watching his owner, Jack picked up the pattern and started tugging on the levers himself. Jack was so smart. He was able to totally take over the signalman’s job that had been held by Wide. Soon, Wide was able to kick back and relax as his furry helper did all of the work switching the rails. According to The Railway Signal, Wide “trained the baboon to such perfection that he was able to sit in his cabin stuffing birds, etc, while the animal, which was chained up outside, pulled all the levers and points.”

One day, as the story goes, an upper-class train passenger, looked out the window of the train and saw that a baboon, and not a human, was manning the gears. Of course, this brought outrage, and a complaint to the railway authorities. The authorities decided not to act in haste and fire Wide, decided to resolve the complaint by testing the baboon’s abilities. The result of that test was a group of astounded officials. “Jack knows the signal whistle as well as I do, also every one of the levers,” wrote railway superintendent George B Howe, who visited the baboon sometime around 1890. “It was very touching to see  his fondness for his master. As I drew near they were both sitting on the trolley. The baboon’s arms round his master’s neck, the other stroking Wide’s face.”

his fondness for his master. As I drew near they were both sitting on the trolley. The baboon’s arms round his master’s neck, the other stroking Wide’s face.”

The complaint was disregarded and Jack was reportedly given an official employment number, and was paid 20 cents a day and half a bottle of beer weekly. Jack passed away in 1890, after developing tuberculosis. It was a sad day for all who knew him. Jack had worked the rails for nine years, without ever making a mistake. That shows that animals can be trained to do things in a responsible way, and do their job perfectly.

When World War I broke out, many young men were called into service. It is a common part of war…one we all know about, and most parents dread. World War I was unique in one way, however. There was a soldier who went to war who was different. He was not different in the way he served exactly, but rather in some other very obvious ways. His speech was different. His mentality was somewhat different, and his looks were different. I’m not being discriminatory, but simply stating a fact. His name was Jackie, and he was different because he was a monkey, well actually, he was a Chacma baboon (Papio ursinus). Jackie was found in August 1915 near the Marr’s family farm in Villeria, Pretoria, South Africa by Albert Marr and soon became a beloved pet.

When World War I broke out, many young men were called into service. It is a common part of war…one we all know about, and most parents dread. World War I was unique in one way, however. There was a soldier who went to war who was different. He was not different in the way he served exactly, but rather in some other very obvious ways. His speech was different. His mentality was somewhat different, and his looks were different. I’m not being discriminatory, but simply stating a fact. His name was Jackie, and he was different because he was a monkey, well actually, he was a Chacma baboon (Papio ursinus). Jackie was found in August 1915 near the Marr’s family farm in Villeria, Pretoria, South Africa by Albert Marr and soon became a beloved pet.

When the war started and the young men were drafted, Albert was no exception. The thing is that Albert couldn’t stand the thought of leaving his beloved pet at home. Albert was assigned to service at Potchefstroom in the North West province of South Africa as private number 4927 for the newly formed 3rd Transvaal Regiment of the 1st South African Infantry Brigade on the 25th August 1915. He approached his superiors and requested that Jackie be allowed to go with him and amazingly was given permission. I’m sure that seems as odd to you as it did to me, but it goes further. Once enlisted Jackie was given a special uniform complete with buttons, a cap, regimental badges, a pay book and his own rations. He was a true member of the regiment, but that doesn’t mean he was accepted as a part of it…at first anyway. The other members of the regiment initially ignored Jackie, but like most people around a monkey, or in this case, baboon, it was hard to ignore him for very long. Jackie soon became the official mascot of the 3rd Transvaal Regiment. Jackie took his duties very seriously, however. He wasn’t there just to eat and fool around!

Jackie was very smart, and when he saw a superior officer passing, he would stand to attention and even provide them with the correct salute. He would light cigarettes for his comrades in arms and was, without a doubt, the best sentry around, due to his great senses of hearing and smelling which allowed him to be able to detect any enemy long before any of his other army mates could even notice their approach. He wasn’t a coddled pet protected for the battles either. Jackie spent three years in the front line amongst the trenches of France and Flanders in Europe. During the Senussi Campaign on 26 February 1916 in Egypt, Jackie’s beloved Albert got wounded on his shoulder by an enemy bullet. Jackie stayed beside him until the stretcher bearers arrived, licking the wound and doing what he could to comfort his friend.

Albert and Jackie both held the rank of private, and in April of 1918, both got injured in the Passchendaele area in Belgium during a heavy fire. With explosions surrounding them, Jackie was seen trying to get some protection by building a little fortress of stones around himself. He didn’t manage to finish his little safe area soon enough, and was hit by a chunk of shrapnel from a shell explosion nearby, which also injured Albert. Jackie’s right leg was seriously wounded and later had to be amputated. Jackie and Albert both made a full recovery and shortly before the armistice, Jackie was promoted to corporal, and awarded a medal for valor.

At the end of April, Jackie was officially discharged at the Maitland Dispersal Camp, Cape Town, South Africa, while wearing on his arm a gold wound stripe and three blue service chevrons indicating three years of frontline service. He was given a parchment discharge paper, a military pension and a Civil Employment Form for

discharged soldiers. After his service, Jackie returned to the Marr’s farm where he lived until May 22, 1921…a sad day for all who knew him. Albert Marr lived until the age of 84 and died in Pretoria in August 1973. Jackie was an amazing Chacma Baboon who, because of a fateful connection, ended up as the only monkey to reach the rank of Corporal of the South African Infantry and fight in Egypt, Belgium and France during World War I. Now that’s amazing!!!

discharged soldiers. After his service, Jackie returned to the Marr’s farm where he lived until May 22, 1921…a sad day for all who knew him. Albert Marr lived until the age of 84 and died in Pretoria in August 1973. Jackie was an amazing Chacma Baboon who, because of a fateful connection, ended up as the only monkey to reach the rank of Corporal of the South African Infantry and fight in Egypt, Belgium and France during World War I. Now that’s amazing!!!