robbery

On December 10, 1968, the 300-million-yen robbery, also known as the 300-million-yen affair or incident, took place in Tokyo, Japan, when a man posing as a police officer on a motorcycle performed a “traffic stop” of some bank employees transferring money and stole about 294 million yen. This as half-century old unsolved heist remains the single largest heist in Japanese history. On that fateful day, four Kokubunji branch employees of the Nihon Shintaku Ginko (Nippon Trust Bank) were transporting 294,307,500 yen (about US$817,520 at 1968 exchange rates) in the trunk of a Nissan Cedric company car. It seems like a rather odd and very unsecure way to transfer such a large sum of money, but apparently, they saw no danger…a mistake they would most certainly regret. The money, contained in metal boxes was to be for bonuses for the employees of Toshiba’s Fuchu factory.

On December 10, 1968, the 300-million-yen robbery, also known as the 300-million-yen affair or incident, took place in Tokyo, Japan, when a man posing as a police officer on a motorcycle performed a “traffic stop” of some bank employees transferring money and stole about 294 million yen. This as half-century old unsolved heist remains the single largest heist in Japanese history. On that fateful day, four Kokubunji branch employees of the Nihon Shintaku Ginko (Nippon Trust Bank) were transporting 294,307,500 yen (about US$817,520 at 1968 exchange rates) in the trunk of a Nissan Cedric company car. It seems like a rather odd and very unsecure way to transfer such a large sum of money, but apparently, they saw no danger…a mistake they would most certainly regret. The money, contained in metal boxes was to be for bonuses for the employees of Toshiba’s Fuchu factory.

As the car proceeded along its route to the home of the bank manager for delivery to the factory, a young man in the uniform of a motorcycle police officer blocked the path of the car. Like most of us would do, when faced with an authority figure telling us to stop, the men in the car obeyed the “officer” and a mere 200 meters from its destination, on a street next to Tokyo Fuchu Prison they stopped. The impersonator informed the bank employees that their bank branch manager’s house had been destroyed by an explosion, and a warning had been received that a bomb had also been planted in the car. The four employees quickly exited the vehicle, while the police officer crawled under the car. Moments later, the “officer” he rolled out, shouting that the car was about to explode and telling the employees to run. Smoke and flames appeared underneath the car. The employees quickly retreated, and “police officer” got into it and drove away. I’m sure it took several moments for the employees to figure out that there was no bomb, and the “officer” wasn’t a selfless hero trying to get the car away from any innocent bystanders…especially when there was no explosion, and the “officer” didn’t come back. They were now faced with a new and unpleasant dilemma…telling their boss they had been duped.

The “police officer” had worked out his story well, telling the bank employees he knew about the bomb because  threatening letters had been sent to the bank manager beforehand. He was also prepared with a warning flare to create the smoke and flames he had ignited while under the car. At some point, the thief abandoned the bank’s car and transferred the metal boxes to another car, which he had stolen beforehand. Then, he also abandoned that car and transferred the boxes into to another previously stolen vehicle. He had laid out his plan very well, but there were, nevertheless, 120 pieces of evidence left at the scene of the crime, including the “police” motorcycle, which had been painted white. Unfortunately, the evidence was mostly common everyday items. It is believed that he scattered them around on purpose to confuse the police investigation…a planned which seems to have worked quite well too.

threatening letters had been sent to the bank manager beforehand. He was also prepared with a warning flare to create the smoke and flames he had ignited while under the car. At some point, the thief abandoned the bank’s car and transferred the metal boxes to another car, which he had stolen beforehand. Then, he also abandoned that car and transferred the boxes into to another previously stolen vehicle. He had laid out his plan very well, but there were, nevertheless, 120 pieces of evidence left at the scene of the crime, including the “police” motorcycle, which had been painted white. Unfortunately, the evidence was mostly common everyday items. It is believed that he scattered them around on purpose to confuse the police investigation…a planned which seems to have worked quite well too.

One suspect was the 19-year-old son of a police officer. That young man died of potassium cyanide poisoning on December 15, 1968. He had no alibi, which may not have meant anything, since the money was not found at the time of his death. His death was deemed a suicide, and he was considered not guilty, according to official record. There was simply no evidence to tie him to the crime. Another, arrest made on December 12, 1969, of a 26-year-old man, who was suspected by the Mainichi Shimbun, proved to be a dead end too, when his alibi checked out. The arrest was initially made on an unrelated charge, but on the day of the robbery, he was taking a proctored examination. The only resulting charge from that arrest was that of “abuse of power” as the arrest was made based on false pretenses.

The police launched a massive investigation, posting 780,000 composite pictures throughout Japan. Amazingly, the list of suspects (or as it really must have been, persons of interest) included 110,000 names. These had to have been people the police thought might possibly be able to carry off such a heist, because it would really be impossible to have that many real suspects. Approximately 170,000 policemen participated in the investigation, which was the largest investigation in Japanese history…or so the story goes. They gathered and examined fingerprints from the scene and comparison of them to those on file. In the end, six million fingerprints on file were compared individually, however not a single match was found.

On November 15, 1975, just before the statute of limitations for that crime was over, a friend of the 19-year-old suspect was arrested on an unrelated charge. He had a large amount of money and was suspected of the  robbery. He was 18 years old when the robbery occurred. The police asked him for an explanation for the large amount of money, but he refused to speak, and they were not able to prove that his money had come from the robbery. In December 1975, after a seven-year investigation, police announced that the statute of limitations on the crime had passed, and that the investigation was at an end. In a further slap to justice, as of 1988, the thief has also been relieved of any civil liabilities, which means that he can tell his story without fear of legal repercussions. Still, no one has ever stepped forward to “tell said story” either, which tends to further exasperate the authorities, because it is the unsolved crimes that torment a police officer the most.

robbery. He was 18 years old when the robbery occurred. The police asked him for an explanation for the large amount of money, but he refused to speak, and they were not able to prove that his money had come from the robbery. In December 1975, after a seven-year investigation, police announced that the statute of limitations on the crime had passed, and that the investigation was at an end. In a further slap to justice, as of 1988, the thief has also been relieved of any civil liabilities, which means that he can tell his story without fear of legal repercussions. Still, no one has ever stepped forward to “tell said story” either, which tends to further exasperate the authorities, because it is the unsolved crimes that torment a police officer the most.

Often when a robbery goes wrong, the would-be robbers decide that the best way out of the situation is to take hostages. The hope is to negotiate a way out of their pending imprisonment. Most hostage takings or sieges last a few hours but on September 28, 1975, The Spaghetti House siege began, and it continued until October 3, 1975. The Spaghetti House was a restaurant in Knightsbridge, London, and when the robbery went wrong, the police were on the scene so quickly that the robbers couldn’t get away. Seeing that they were trapped, the three robbers took the staff down into a storeroom and barricaded themselves in. The three robbers had been involved in black liberation organizations and tried to set the robbery as being politically motivated, thinking that a political standoff might have a better chance of success. The police did not believe them, however, and they stated that this was no more than a criminal act. Finally, they decided that the political ploy was not going to work, so the robbers released all the hostages unharmed after six days. I can’t say for sure that this was the longest robbery siege in history, but if it wasn’t, it ranked right up there. Finally, two of the gunmen gave themselves up, while the ringleader, Franklin Davies, shot himself in the stomach. He survived, and all three were later imprisoned, as were two accomplices. To keep tabs on the situation during the siege, the police used fiber optic camera technology, giving them live surveillance. They monitored the actions and conversations of the gunmen from the audio and visual output. They brought in a forensic psychiatrist to watch the feed and advise the police on the state of the men’s minds, and how to best manage the ongoing negotiations.

Often when a robbery goes wrong, the would-be robbers decide that the best way out of the situation is to take hostages. The hope is to negotiate a way out of their pending imprisonment. Most hostage takings or sieges last a few hours but on September 28, 1975, The Spaghetti House siege began, and it continued until October 3, 1975. The Spaghetti House was a restaurant in Knightsbridge, London, and when the robbery went wrong, the police were on the scene so quickly that the robbers couldn’t get away. Seeing that they were trapped, the three robbers took the staff down into a storeroom and barricaded themselves in. The three robbers had been involved in black liberation organizations and tried to set the robbery as being politically motivated, thinking that a political standoff might have a better chance of success. The police did not believe them, however, and they stated that this was no more than a criminal act. Finally, they decided that the political ploy was not going to work, so the robbers released all the hostages unharmed after six days. I can’t say for sure that this was the longest robbery siege in history, but if it wasn’t, it ranked right up there. Finally, two of the gunmen gave themselves up, while the ringleader, Franklin Davies, shot himself in the stomach. He survived, and all three were later imprisoned, as were two accomplices. To keep tabs on the situation during the siege, the police used fiber optic camera technology, giving them live surveillance. They monitored the actions and conversations of the gunmen from the audio and visual output. They brought in a forensic psychiatrist to watch the feed and advise the police on the state of the men’s minds, and how to best manage the ongoing negotiations.

There were a number of things that potentially led up to the robbery, not that these things were in any way a good excuse. Post-World War II Britain had a shortage of labor. Due to that shortage, the British decided to bring in workers from the British Empire and Commonwealth countries. These people came from poverty areas,  and while they were placed in low-pay, low-skill employment, which forced them to live in poor housing, it probably wasn’t much different than what they came from. Nevertheless, economic circumstances and what were seen by many in the black communities as racist policies applied by the British government, just like in other nations. This led to a rise in militancy, particularly among the West Indian community. The people grew angry, and their feelings were exacerbated by police harassment and discrimination in the education sector. The director of the Institute of Race Relations in the mid-1970s, Ambalavaner Sivanandan said that while the first generation had become partly assimilated into British society, the second generation were increasingly rebellious. These robbers were a part of that second generation.

and while they were placed in low-pay, low-skill employment, which forced them to live in poor housing, it probably wasn’t much different than what they came from. Nevertheless, economic circumstances and what were seen by many in the black communities as racist policies applied by the British government, just like in other nations. This led to a rise in militancy, particularly among the West Indian community. The people grew angry, and their feelings were exacerbated by police harassment and discrimination in the education sector. The director of the Institute of Race Relations in the mid-1970s, Ambalavaner Sivanandan said that while the first generation had become partly assimilated into British society, the second generation were increasingly rebellious. These robbers were a part of that second generation.

The ringleader, Franklin Davies was a 28-year-old Nigerian student who had previously served time in prison for armed robbery. The two men with him were Wesley Dick (later known as Shujaa Moshesh), who was a 24-year-old West Indian; and Anthony “Bonsu” Munroe, a 22-year-old Guyanese. The men were all involved in black liberation organizations at one time or another. Davies had tried to enlist in the guerrilla armies of Zimbabwe African National Union and FRELIMO in Africa. While Munroe had links to the Black Power movement. Dick was an attendee at meetings of the Black Panthers, the Black Liberation Front (BLF), the Fasimba, and the Black Unity and Freedom Party. He regularly visited the offices of the Institute of Race Relations to volunteer and access their library. Sivanandan and the historian Rob Waters identify that the three men were attempting to obtain money to “finance black supplementary schools and support African liberation struggles.”

By the mid-1970s the branch managers started a weekly tradition of closing the London-based Spaghetti House restaurant chain to meet at the company’s Knightsbridge branch. During that time, the outlet would be closed, but managers would deposit the week’s takings there, before it was paid into a night safe at a nearby bank. Of course, that was a well-known fact. So, at approximately 1:30am on Sunday, September 28, 1975, Davies, Moshesh, and Munroe entered the Knightsbridge branch of the Spaghetti House. One carried a sawed-off shotgun, and the others had handguns. The three men burst in and demanded the week’s takings from the chain, which was between £11,000 and £13,000. The restaurant was dimly lit, and it gave the staff a chance to  hide the briefcases of money under the tables. Now infuriated, the three men forced the staff down into the back, but the company’s general manager managed to escape out the rear fire escape.

hide the briefcases of money under the tables. Now infuriated, the three men forced the staff down into the back, but the company’s general manager managed to escape out the rear fire escape.

He quickly called the Metropolitan Police, who were at the scene within minutes. The getaway driver, Samuel Addison, realized that the plan was going wrong, so he decided that it was every man for himself, and drove off in a stolen Ford. The police entered the ground floor, so Davies and his colleagues forced the staff into a rear storeroom measuring 14 by 10 feet, locked the door, barricaded it with beer kegs. They began shouting at the police that they would shoot if they approached the door. The police surrounded the building, and the siege began. It would finally end on October 3, 1975, with the surrender of the robbers, and later the location and arrest of the two accomplices.

.

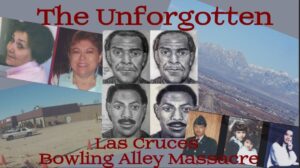

Evil can be just around the corner, and sadly, sometimes, the evil doers walk away without being punished for their crimes. On the morning of February 10, 1990, the staff at Las Cruces Bowl were busy getting ready for the Saturday bowling crowd, when two armed men walked in through an unlocked door. The men were there to rob the place. They could have worn masks, or they could have just robbed the place and fled the scene, but they had no intention of being caught, and that meant that they couldn’t leave witnesses.

Evil can be just around the corner, and sadly, sometimes, the evil doers walk away without being punished for their crimes. On the morning of February 10, 1990, the staff at Las Cruces Bowl were busy getting ready for the Saturday bowling crowd, when two armed men walked in through an unlocked door. The men were there to rob the place. They could have worn masks, or they could have just robbed the place and fled the scene, but they had no intention of being caught, and that meant that they couldn’t leave witnesses.

Stephanie C Senac, 34, who was the bowling alley manager, was in her office preparing to open the for the day. Her 12-year-old daughter Melissa Repass and Melissa’s 13-year-old friend Amy Houser were there to supervise the alley’s day care. The gunmen took them into the office, where they robbed them of a mere $4,000 to $5,000. As robberies go, it was practically nothing. When bowling alley mechanic Steven Teran came in with his two young daughters, Paula Holguin and Valerie Teran, they were totally unprepared for what faced them. Teran was unable to find a  babysitter for his daughters that day, so he had decided that he would drop them at the bowling alley daycare for the Melissa and Amy to watch. As the robbers took cash from the safe, the seven unfortunate people, including Teran and his daughters; cook Ida Holguin (no relation to Paula); manager Stephanie Senac, her daughter, and her daughter’s friend tried to be cooperative in the hope of making it out alive, but the men told them to get down on the ground. Then they shot all of the victims multiple times at close range, aiming mostly for their heads. When the shooting was over, they were still not satisfied with how things stood, so they set fire to some papers in the office of the bowling alley and left.

babysitter for his daughters that day, so he had decided that he would drop them at the bowling alley daycare for the Melissa and Amy to watch. As the robbers took cash from the safe, the seven unfortunate people, including Teran and his daughters; cook Ida Holguin (no relation to Paula); manager Stephanie Senac, her daughter, and her daughter’s friend tried to be cooperative in the hope of making it out alive, but the men told them to get down on the ground. Then they shot all of the victims multiple times at close range, aiming mostly for their heads. When the shooting was over, they were still not satisfied with how things stood, so they set fire to some papers in the office of the bowling alley and left.

Miraculously, Ida, Senac, and Melissa all survived. Melissa, despite being shot five times, was able to call 911. Unfortunately, the fire and subsequent efforts to put out the fire destroyed most of the evidence. In those days, forensics mostly involved fingerprints, which were in abundance in the bowling alley. DNA was not really as  developed at that time. Investigators were unable to discern which fingerprints were meaningful. There were witnesses, of course, who identified the suspects as two Hispanic men, in their 30s or 40s. Roadblocks were quickly set up by the police, to screen anyone leaving town. Still, the suspects were never found. Despite a frequent stream of tips, authorities are no closer to identifying and arresting the suspects today than they were 32 years ago…even with age enhanced pictures. The murders have been shown on multiple crime solving programs, including on Unsolved Mysteries two and a half months after the murders, and on America’s Most Wanted twice, once in November 2004 and again in March 2010. In the end, the crime also took the life of Stephanie Senac, who died in 1999…nine years later, due to complications from her injuries. The men got away with just $4,000 to $5,000, but the victims paid dearly.

developed at that time. Investigators were unable to discern which fingerprints were meaningful. There were witnesses, of course, who identified the suspects as two Hispanic men, in their 30s or 40s. Roadblocks were quickly set up by the police, to screen anyone leaving town. Still, the suspects were never found. Despite a frequent stream of tips, authorities are no closer to identifying and arresting the suspects today than they were 32 years ago…even with age enhanced pictures. The murders have been shown on multiple crime solving programs, including on Unsolved Mysteries two and a half months after the murders, and on America’s Most Wanted twice, once in November 2004 and again in March 2010. In the end, the crime also took the life of Stephanie Senac, who died in 1999…nine years later, due to complications from her injuries. The men got away with just $4,000 to $5,000, but the victims paid dearly.

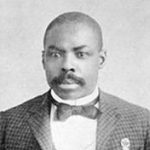

I can imagine a number of nicknames a stagecoach driver might want to have, one that no one would want to have. George Green was one of the most popular stagecoach drivers in the Sierra Mountain Range, driving for the Pioneer Stage Company between Placerville, California and Virginia City, Nevada in the 1860s. George had the nickname “Baldy” because of the sparse amount of hair he had on the top of his head. It was not the nickname “Baldy” that George would learn to hate, however. George was known for his good looks, standing about six feet tall with a large full mustache, but it was not his good looks or large mustache that earned him the nickname he hated either.

I can imagine a number of nicknames a stagecoach driver might want to have, one that no one would want to have. George Green was one of the most popular stagecoach drivers in the Sierra Mountain Range, driving for the Pioneer Stage Company between Placerville, California and Virginia City, Nevada in the 1860s. George had the nickname “Baldy” because of the sparse amount of hair he had on the top of his head. It was not the nickname “Baldy” that George would learn to hate, however. George was known for his good looks, standing about six feet tall with a large full mustache, but it was not his good looks or large mustache that earned him the nickname he hated either.

During his days as a stagecoach driver, Green drove many famous people including Ben Holladay, Horace Greeley, and Vice-President Schuyler Colfax. Nevertheless, Green was apparently not a very scary driver. On May 22, 1865, near Silver City, Nevada, three men robbed his stage of $10,000 in gold and greenbacks. I guess word must have gotten around, because more robberies followed that first one, and not only would the robbers not leave him alone, but the robberies were big news and the stories sold lots of newspapers. The Territorial Enterprise commented that Green had narrowly escaped scalping, and someone placed a sign near the robbery location saying, “Wells-Fargo Distributing Office, Baldy Green, Mgr.”

Green just couldn’t catch a break. Two years later his stage was robbed twice on successive days, and following another robbery on June 10, 1868, Virginia City’s Territorial Enterprise stated: “Baldy Green is exceedingly unlucky, as the road agents appear to have singled him out as their special man to halt and plunder, and they always come at him with shotguns.” Two more robberies occurred the same month, and you might say that the  writing was on the wall. No one came right out an accused Green of being involved, but it had come to the point that they couldn’t take the risk of keeping him on anymore. Green was fired. Whether he was guilty or not, he was the driver most likely to be robbed. While he was never given that nickname, it is rather a fitting one.

writing was on the wall. No one came right out an accused Green of being involved, but it had come to the point that they couldn’t take the risk of keeping him on anymore. Green was fired. Whether he was guilty or not, he was the driver most likely to be robbed. While he was never given that nickname, it is rather a fitting one.

Green didn’t let that stop him, however. He then went to hauling freight in Pioche, Nevada. I guess either he figured out how to stop the robberies, or freight haulers were less likely to be robbed. Either way, he managed to have more success in that trade that the stagecoach career. Later on, he even served as Justice of the Peace in Humboldt County, Nevada.

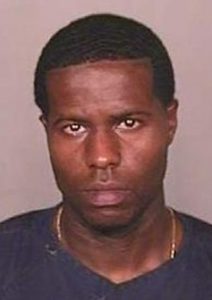

Prisoners have tried to escape ever since there have been prisons. It is the nature of the situation. No one likes to be locked up. Most escape attempts are not successful, and few are what we would consider well planned, but in the case of Florida prison inmates, Charles Walker and Joseph Jenkins, some kind of good planning must have gone into the escape plan. The two men were serving life sentences, without the possibility of parole, for murder, and so I guess they had nothing to lose by getting caught in an escape attempt. Jenkins was incarcerated for a 1998 murder and armed robbery and a 1997 auto theft. He has been in prison since 2000. Walker was imprisoned for a 1999 murder and has been in custody since 2001.

Prisoners have tried to escape ever since there have been prisons. It is the nature of the situation. No one likes to be locked up. Most escape attempts are not successful, and few are what we would consider well planned, but in the case of Florida prison inmates, Charles Walker and Joseph Jenkins, some kind of good planning must have gone into the escape plan. The two men were serving life sentences, without the possibility of parole, for murder, and so I guess they had nothing to lose by getting caught in an escape attempt. Jenkins was incarcerated for a 1998 murder and armed robbery and a 1997 auto theft. He has been in prison since 2000. Walker was imprisoned for a 1999 murder and has been in custody since 2001.

The men were serving their time in a Panhandle prison called Franklin Correctional Institution in Carrabelle, Florida. accidentally released two inmates from a Panhandle prison who are convicted murderers, according to published reports. Somehow, Walker and Jenkins, both 34, were able to obtain fraudulent orders of sentence modification. Based on those modifications, Jenkins was released on September 27, 2013, and Walker was released on October 8, 2013. Both were former residents of Orlando. Their release was apparently “in accordance with Department of Corrections policy and procedure. However, both of their releases were based on fraudulent modifications that had been made to court orders,” Department of Corrections secretary Michael Crews said.

The judge whose name is on the forged documents is Belvin Perry, Orange County chief judge, who presided  over the Casey Anthony case. Perry’s office said that the judge’s signature was forged in the paperwork calling for reduced sentences for the convicted killers. Apparently, however, while the false documents had problems the one thing that was correct was the judges signature. The judge denies any wrongdoing, saying “It is quite evident that someone forged a court document, filed a motion, and that someone with the aid of a computer, lifted my signature off previous signed documents, which are public reports, affixed that to the document, sent it to the clerk’s office. It was processed and forwarded to doc and the defendant ended up being released,” Perry maintains. He also says, “I have never seen anything like this. You have to give them an A for being imaginative and effective.” The reality is that this was not the first time a prisoner managed to obtain false documents, and probably wont be the last, since no one was caught in this act. The prison waited 17 days before notifying the authorities of the escape. Cybercrime is the newest thing. Easy to perform, hard to catch.

over the Casey Anthony case. Perry’s office said that the judge’s signature was forged in the paperwork calling for reduced sentences for the convicted killers. Apparently, however, while the false documents had problems the one thing that was correct was the judges signature. The judge denies any wrongdoing, saying “It is quite evident that someone forged a court document, filed a motion, and that someone with the aid of a computer, lifted my signature off previous signed documents, which are public reports, affixed that to the document, sent it to the clerk’s office. It was processed and forwarded to doc and the defendant ended up being released,” Perry maintains. He also says, “I have never seen anything like this. You have to give them an A for being imaginative and effective.” The reality is that this was not the first time a prisoner managed to obtain false documents, and probably wont be the last, since no one was caught in this act. The prison waited 17 days before notifying the authorities of the escape. Cybercrime is the newest thing. Easy to perform, hard to catch.

Seldom does it happen that money from a robbery is never recovered, but that is the case for approximately $28,000 in gold and silver coins, which have been missing for more than a century. The money came from the little known Wham Paymaster Robbery, which occurred near Pima, Arizona. Eight suspects were caught and tried for the crime, but in the end, they walked away free men. The circumstances of the robbery remain an unsolved mystery to this day. The robbery of US Army Paymaster, Major Joseph Washington Wham occurred on May 11, 1889 in the early morning hours. Wham was preparing to make the trip from Fort Grant to Fort Thomas to pay the soldiers’ salaries. The day before, he had distributed the pay to Fort Grant. That day, he was to pay the men at Fort Thomas, Camp San Carlos, and Fort Apache.

Seldom does it happen that money from a robbery is never recovered, but that is the case for approximately $28,000 in gold and silver coins, which have been missing for more than a century. The money came from the little known Wham Paymaster Robbery, which occurred near Pima, Arizona. Eight suspects were caught and tried for the crime, but in the end, they walked away free men. The circumstances of the robbery remain an unsolved mystery to this day. The robbery of US Army Paymaster, Major Joseph Washington Wham occurred on May 11, 1889 in the early morning hours. Wham was preparing to make the trip from Fort Grant to Fort Thomas to pay the soldiers’ salaries. The day before, he had distributed the pay to Fort Grant. That day, he was to pay the men at Fort Thomas, Camp San Carlos, and Fort Apache.

Wham, along with his clerk, William Gibbon, and Private Caldwell, his servant and mule tender, climbed into a canopied wagon driven by Buffalo Soldier, Private Hamilton Lewis for the 46 mile trip to Fort Thomas. The payroll Wham was still in possession of was more than $28,000 in gold and silver coins. It was locked in an oak strongbox in the wagon. Given the amount of money Wham was carrying, he was heavily escorted by nine Buffalo Soldiers of the 24th Infantry on horseback, as well as a wagon that carried two privates of the 10th Cavalry (also an African-American regiment) that was driven by a civilian employee of the Quartermaster Department. Everyone was heavily armed, except Wham, his clerk and the two drivers. An African-American female gambler named Frankie Campbell, joined them at the last minute. She wanted to ride along with them to be in Fort Thomas when the soldiers got paid…to stir up a game or two, I’m sure.

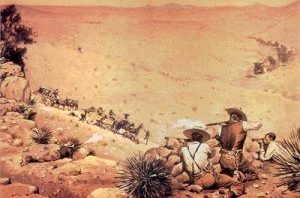

About 15 miles west of Pima in the Gila River Valley, just after midday, the caravan came to a stop. A large boulder was blocking the road, and the wagons were unable to get around it. The soldiers lay down their weapons in order to dislodge the large rock. They barely got started when a cry came from a ledge some 60 feet above on the adjacent hill, “Look out, you black sons of bitches!” and bullets began to hail down upon the soldiers. Three of the 12 mules pulling the wagons were killed and the other animals panicked, rearing and pulling both vehicles off the road. The soldiers ran for their guns and took cover to fight the barrage of bullets raining down on them from the hills. Sergeant Benjamin Brown was shot but continued to return fire with his revolver. Private James Young ran through heavy gunfire and carried Brown more than 100 yards to safety. Corporal Isaiah Mays then took command, ordering the entourage to retreat to a creek bed about 300 yards away, while Major Wham strongly protested. The battle continued to rage on for about a half an hour as the soldiers valiantly tried to protect the payload. However, eight of Wham’s eleven-man escort were severely wounded and the battle had become extremely one-sided. During all this, gambler, Frankie Campbell, who had been riding ahead of the caravan, had been thrown from her horse and had taken cover.

With the soldiers hidden, wounded, and severely out gunned, five bandits then made their way to the wagon. Once there, they cracked the strongbox with an ax, and carried off the U.S. Treasury sacks filled with the coins. The soldiers counted 12 outlaws, who made their escape. At about 3:00pm those, who could manage, made their way from the creek bed to the wagons. They spliced harnesses together, gathered some of the surviving mules, and finally made their way to Fort Thomas, arriving about 5:30pm. The soldiers left, Frankie Campbell to tend to the severely wounded, including Sergeant Benjamin Brown. These men would be brought in later. Amazingly, all of the soldiers would survive their wounds, so she must have done a good job with their care.

Amazingly, several of the bandits, who had not thought to cover their faces during the gun battle, were recognized and very soon arrested. US Deputy Marshal William Kidder Meade, and the Graham County Sheriff arrested 11 men, most of whom were citizens of Pima, Arizona. Seven were bound over for trial. The men were Gilbert Webb, the Mayor of Pima at the time. Webb was the suspected leader of the gang. Also arrested was his son, Wilfred. These men were already suspected of numerous thefts in the area. Along with the Webbs, brothers Lyman and Warren Follett, as well as David Rogers, Thomas Lamb, and Mark Cunningham, all of whom worked as cowboys for Gilbert Webb. Strangely, the men were charged with the robbery, but no one was ever charged with the shooting.

The trial in Federal Court in Tucson was held in November lasted 33 days. It was big news in the Southwest. With all the witnesses, I cant figure out how they could not be found guilty, but from the beginning, the trial involved major politics and infighting, including removing the original judge. In all, 165 witnesses testified at the trial, including five Buffalo Soldiers who identified three of the accused. Another witness testified that he had personally seen some of the men hiding the loot in a haystack and burning the US treasury sacks. Several other witnesses testified that they had seen members of the accused in the area of the ambush the day before…probably setting up their “hideouts” from which the ambush took place. Strangely, Frankie Campbell, who had stated she recognized several of the bandits, including the leader, Gilbert Webb, was never called to testify. The defense lawyer was the famed Marcus Aurelius Smith, and in the end all of the men were acquitted.

Afterward, it was widely claimed that political pressure from the acting governor allowed the thieves to go free. The entire case was a hotbed of religion, racism, and politics, as Pima, Arizona was founded as a Mormon Colony, of which Gilbert Webb was the mayor, one of the most influential men in the area, and came from a long line of pioneer Mormons. He was also known in the area as a generous man, providing jobs for struggling neighbors, extending credit, and providing provisions. Though most of the other accused men were not Mormons, they all lived in the Mormon colony, having many ties to the church through friends and relatives. Be it politics or religion, a great injustice was done that day. Many locals viewed the robbery and trial as an embarrassing disgrace to the town and its people, and to talk about it about might offend friends or neighbors, or bring shame upon the colony. Therefore, the robbery was kept largely under wraps. The locals called the robbers “Latter-Day Robin Hoods.”

In the meantime, Major Joseph Washington Wham, as the commanding officer, was held accountable for the loss of the money but was later absolved of any guilt. Two of the Buffalo Soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor for their part in the gun battle with the bandits. Although shot in the abdomen, Sergeant Benjamin Brown continued the fight until he was further wounded in both arms. Corporal Isaiah Mays also received the Medal of Honor, as near the end of the gun battle, though shot in the legs, he “walked and crawled two miles to Cottonwood Ranch and gave the alarm.” Other Buffalo Soldiers cited for bravery in the incident received the Certificate of Merit. These included Hamilton Lewis, Squire Williams, George Arrington, James Wheeler, Benjamin Burge, Thomas Hams, James Young, and Julius Harrison of the 10th Cavalry and 24th Infantry. US

Deputy Marshal Meade, who would bring in the bandits, would say of the soldiers, “I am satisfied a braver or better defense could not have been made under like circumstances.” Throughout the years, the robbery has created a number of various treasure tales, suggesting that some of the coins are still hidden in the area somewhere. However; with all of the suspects set free, this would seem doubtful.

Deputy Marshal Meade, who would bring in the bandits, would say of the soldiers, “I am satisfied a braver or better defense could not have been made under like circumstances.” Throughout the years, the robbery has created a number of various treasure tales, suggesting that some of the coins are still hidden in the area somewhere. However; with all of the suspects set free, this would seem doubtful.

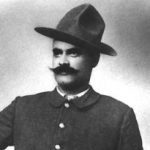

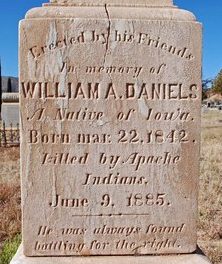

Many men helped to tame the wild west, but unfortunately things didn’t always go exactly as the lawmen planned. Billy Daniels was a pretty typical lawman, but like the thousands of courageous young men and women who helped tame the Wild West, whose names and stories have since been largely forgotten, Billy was not a well remembered lawman. For every Wild Bill Hickok or Wyatt Earp, who have been immortalized by the dramatic exaggerations of dime novelists and journalists, the West had dozens of men like Billy Daniels, who quietly did their duty with little fanfare, celebration, or thanks.

Many men helped to tame the wild west, but unfortunately things didn’t always go exactly as the lawmen planned. Billy Daniels was a pretty typical lawman, but like the thousands of courageous young men and women who helped tame the Wild West, whose names and stories have since been largely forgotten, Billy was not a well remembered lawman. For every Wild Bill Hickok or Wyatt Earp, who have been immortalized by the dramatic exaggerations of dime novelists and journalists, the West had dozens of men like Billy Daniels, who quietly did their duty with little fanfare, celebration, or thanks.

On December 8, 1883, five desperadoes led by Daniel “Big Dan” Dowd, rode into the booming mining town of Bisbee, Arizona. Dowd had heard that the $7,000 payroll of the Copper Queen Mine would be in the vault at the Bisbee General Store. He had planned to surprise the store owners, and make off with the payroll, but things didn’t go exactly as planned. When the outlaws barged into the store with their guns drawn, demanding the payroll, they discovered, to Dowd’s disappointment, that they were too early. The payroll hadn’t arrived yet. The outlaws quickly gathered up what money there was, somewhere between $900 to $3,000, and took valuable rings and watches from the customers who just happened to be in the store. After the robbery, for reasons that are unclear…but possibly, anger…the robbery turned into a slaughter. When the five desperadoes rode away, they left behind four dead or dying people, including Deputy Sheriff Tom Smith and a Bisbee woman named Anna Roberts.

The people of Arizona were stunned. The people had cooperated with the outlaws. There was no reason to kill  those people. The killings were a completely senseless show of brutality. The newspapers called it the “Bisbee Massacre.” The sheriff quickly organized citizen posses to track down the killers, placing Deputy Sheriff Billy Daniels at the head of one. Unfortunately, the posses soon ran out of clues and the trail grew cold. Most of the citizen members gave up, but not Daniels. He stubbornly continued the pursuit alone. Daniels eventually learned the identities of the five men from area ranchers and began to track them down one by one.

those people. The killings were a completely senseless show of brutality. The newspapers called it the “Bisbee Massacre.” The sheriff quickly organized citizen posses to track down the killers, placing Deputy Sheriff Billy Daniels at the head of one. Unfortunately, the posses soon ran out of clues and the trail grew cold. Most of the citizen members gave up, but not Daniels. He stubbornly continued the pursuit alone. Daniels eventually learned the identities of the five men from area ranchers and began to track them down one by one.

Daniels found one of the killers in Deming, New Mexico, and arrested him. He then learned from a Mexican informant that the gang leader, Big Dan Dowd, had fled south of the border to a hideout at Sabinal, Chihuahua. Daniels went under cover, disguising himself as an ore buyer. He tricked Dowd into a meeting and took him prisoner. A few weeks later, Daniels returned to Mexico and arrested another of the outlaws. Other law officers apprehended the remaining two members of the gang. A jury in Tombstone, Arizona, quickly convicted all five men. They were sentenced to be hanged simultaneously. As the noose was fitted around his neck on the five-man gallows, Big Dan reportedly muttered, “This is a regular killing machine.”

Daniels ran for sheriff the net year, but oddly lost. I would think that a hometown hero would be a shoo-in. After all he had done for the town, it would seem that being the sheriff was a thankless job. He found a new  position as an inspector of customs. The job required him to travel all around the vast and often isolated Arizona countryside, where various bands of hostile Apache Indians were a serious danger. Early on the morning of June 10, 1885, Daniels and two companions were riding up a narrow canyon trail in the Mule Mountains east of Bisbee. Daniels, who was in the lead, rode into an Apache ambush. The first bullets killed his horse, and the animal collapsed, pinning Daniels to the ground. Trapped, Daniels used his rifle to defend himself as best he could, but the Apache quickly overwhelmed him and cut his throat. A mere two years after Arizona Deputy Sheriff William Daniels apprehended three of the five outlaws responsible for the Bisbee Massacre, it was an Apache Indians ambush that would end his life. His two companions escaped with their lives and returned the next day with a posse. They found Daniels’ badly mutilated corpse but were unable to track the Apache Indians who murdered him. I guess they lacked Daniels’ under cover or investigative skills.

position as an inspector of customs. The job required him to travel all around the vast and often isolated Arizona countryside, where various bands of hostile Apache Indians were a serious danger. Early on the morning of June 10, 1885, Daniels and two companions were riding up a narrow canyon trail in the Mule Mountains east of Bisbee. Daniels, who was in the lead, rode into an Apache ambush. The first bullets killed his horse, and the animal collapsed, pinning Daniels to the ground. Trapped, Daniels used his rifle to defend himself as best he could, but the Apache quickly overwhelmed him and cut his throat. A mere two years after Arizona Deputy Sheriff William Daniels apprehended three of the five outlaws responsible for the Bisbee Massacre, it was an Apache Indians ambush that would end his life. His two companions escaped with their lives and returned the next day with a posse. They found Daniels’ badly mutilated corpse but were unable to track the Apache Indians who murdered him. I guess they lacked Daniels’ under cover or investigative skills.

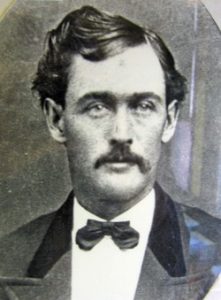

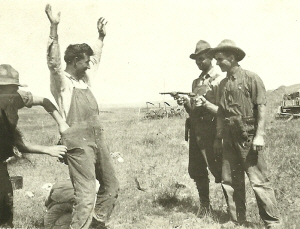

Looking through old photographs from a time when I didn’t even realize that cameras were something lots of people had, it occurred to me that when these pictures were taken, the people in them were still trying to figure them out. It was probably hard to figure out what pictures to take. I’m sure they felt funny posing in all the normal ways. I’m sure they were almost embarrassed when they first started posing for those pictures, and much like people were embarrassed about home movies when they came out. People used to run and hide, or even covering the lens to avoid being filmed.

Looking through old photographs from a time when I didn’t even realize that cameras were something lots of people had, it occurred to me that when these pictures were taken, the people in them were still trying to figure them out. It was probably hard to figure out what pictures to take. I’m sure they felt funny posing in all the normal ways. I’m sure they were almost embarrassed when they first started posing for those pictures, and much like people were embarrassed about home movies when they came out. People used to run and hide, or even covering the lens to avoid being filmed.

I started thinking about the number of pictures I have seen in the past few years that were taken in the 1800’s. it seems that they finally warmed up to the idea of picture taking by posing like they were in a robbery situation. I suppose that a robbery picture was something they could laugh about, so they were able to relax and enjoy the whole picture taking process. It seems that pictures of robberies were what we in this day and age would have called now trending. It was the thing everyone did, like the  shocked look photo, the exaggerated kiss photo, or the angry look photo. It was just something to make people laugh.

shocked look photo, the exaggerated kiss photo, or the angry look photo. It was just something to make people laugh.

Acting goofy in the pictures probably broke the ice to a degree. It made the feeling of being embarrassed a little less noticeable to them. Many people are nervous about photos, in fact, I would say that most of us feel that way at some time or another. Maybe we should all try this trend that seemed to sweep the nation during those years. If nothing else, we would get a good laugh about it. I guess that’s why the latest fad in pictures come about…to laugh about something new that is now trending.

Sometimes I think my family had a lot of comedians in its past. As I look through the pictures from every part of my family, I continue to come up with pictures that are obviously staged intending to get a reaction. So many of the pictures I have seen from the past have families sitting in a studio without one smile among them, so it is surprising to see random pictures that show the subjects posed in odd ways or acting out moments of the old west. At first I thought these were post cards…until I recognized my grandfathers and other family members in the pictures. They were just posing for pictures that they could send back home to get a laugh out of the family back there, or just to show their friends. Either way, it tells me that my family has some great imaginations or a funny bone.

Sometimes I think my family had a lot of comedians in its past. As I look through the pictures from every part of my family, I continue to come up with pictures that are obviously staged intending to get a reaction. So many of the pictures I have seen from the past have families sitting in a studio without one smile among them, so it is surprising to see random pictures that show the subjects posed in odd ways or acting out moments of the old west. At first I thought these were post cards…until I recognized my grandfathers and other family members in the pictures. They were just posing for pictures that they could send back home to get a laugh out of the family back there, or just to show their friends. Either way, it tells me that my family has some great imaginations or a funny bone.

When I first looked at this picture, I didn’t notice anything unusual, but upon closer examination, I saw the man I believe to be my great uncle low to the ground in front of the plow. At first I thought I was seeing things. I looked again thinking it might be a child, but it was definitely a man. Then I wondered how he was so low to the ground. He looked like he was in a hole up to his waist, but that was not the case. No, he was actually sitting in the furrow, so that it looked like he had just been plowed up. And the funny thing was that he was able to keep a perfectly straight face. Now I would have been laughing for sure if I was trying to pull that off. I guess that there are people who just have a knack for keeping a straight face in a joke situation.

Now that isn’t always the case, however. When my grandfather was involved  in a mock hold up, they simply couldn’t keep a straight face, including the intended victim. Those situations can be as funny as the ones where the comedian can keep a straight face, because when they get to laughing, it is contagious. You just laugh in spite of yourself. And that’s ok too. I have found many interesting characters in my family’s past, and they are each interesting in different ways. I think I would have enjoyed very much getting to know all of them. The comedians would have been especially fun, because there would never be a dull moment, and when you think about it, we can all use a good laugh from time to time.

in a mock hold up, they simply couldn’t keep a straight face, including the intended victim. Those situations can be as funny as the ones where the comedian can keep a straight face, because when they get to laughing, it is contagious. You just laugh in spite of yourself. And that’s ok too. I have found many interesting characters in my family’s past, and they are each interesting in different ways. I think I would have enjoyed very much getting to know all of them. The comedians would have been especially fun, because there would never be a dull moment, and when you think about it, we can all use a good laugh from time to time.