revolutionary war

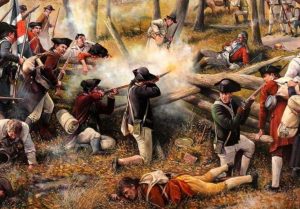

You have probably heard of the famous “Shot Heard Round the World?” It is a phrase referring to several historical incidents, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in 1914, and particularly the beginning of the American Revolutionary War in 1775. Tensions had been mounting because colonists were frustrated as Britain forced them to pay taxes. The big problem was that they did not give them any representation in the British Parliament. The colonists were fair minded people and this flew in the face of that fairness. They rallied behind the phrase, “no taxation without representation.” The first shots rang out on the morning of April 19, 1775 in Lexington, Massachusetts.

You have probably heard of the famous “Shot Heard Round the World?” It is a phrase referring to several historical incidents, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in 1914, and particularly the beginning of the American Revolutionary War in 1775. Tensions had been mounting because colonists were frustrated as Britain forced them to pay taxes. The big problem was that they did not give them any representation in the British Parliament. The colonists were fair minded people and this flew in the face of that fairness. They rallied behind the phrase, “no taxation without representation.” The first shots rang out on the morning of April 19, 1775 in Lexington, Massachusetts.

At the Battle of Bunker Hill, colonial officer William Prescott ordered, “Do not fire until you see the whites of their eyes!” His troops had the courage and discipline to hold their fire until the enemy was near, an early sign that the rag-tag American army had a chance at defeating the well-trained, well-armed British troops. Congress chose George Washington as commander and chief of America’s armed forces. The Battle of Saratoga was the first great American victory of the war and is widely believed to have been the turning point that led America to triumph over Britain. The Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783, and at last, Great Britain acknowledged America’s  independence. The treaty established a northern boundary with Canada and set the Mississippi River as the western boundary. In all 217,000 men took part in the war, and 4,435 lost their lives. Most people know all or at least most of this…or at least have read about it.

independence. The treaty established a northern boundary with Canada and set the Mississippi River as the western boundary. In all 217,000 men took part in the war, and 4,435 lost their lives. Most people know all or at least most of this…or at least have read about it.

However, you might not know that the Revolutionary War almost started early thanks to Sarah Tarrant, a nurse with a fiery temper who lived in Salem, Massachusetts in 1775, hurled insults at the retreating redcoats aimed his musket at her, and she dared him, “Fire, if you have the courage, but I doubt it.” No shots were fired, and the British, having found no weapons, left the town. Had he shot her, the war would have started earlier than it did.

The American Revolution was a serious embarrassment to Britain, and especially to King George III. The king had to admit that things weren’t going well in the colonies…at least not where Britain was concerned. By now, the colonists had signed the Declaration of Independence that summer, and they were not going to be moved from achieving their goal to be a sovereign nation.

The American Revolution was a serious embarrassment to Britain, and especially to King George III. The king had to admit that things weren’t going well in the colonies…at least not where Britain was concerned. By now, the colonists had signed the Declaration of Independence that summer, and they were not going to be moved from achieving their goal to be a sovereign nation.

On this day, October 31, 1776, the king give a speech to the British Parliament, telling them about the signing of the United States Declaration of Independence and the revolutionary leaders who signed it, saying, “for daring and desperate is the spirit of those leaders, whose object has always been dominion and power, that they have now openly renounced all allegiance to the crown, and all political connection with this country.” I’m sure he felt that the colonists were rebels, who were not worth wasting time on by now, and he  hoped he could walk away from them without losing face any more than he already had. The British never intended for the United States to be anything more than the colones. The king went on to inform Parliament of the successful British victory over General George Washington and the Continental Army at the Battle of Long Island on August 27, 1776, but warned them that, “notwithstanding the fair prospect, it was necessary to prepare for another campaign.” Somehow, the king had the idea that there was still hope to keep the colonies.

hoped he could walk away from them without losing face any more than he already had. The British never intended for the United States to be anything more than the colones. The king went on to inform Parliament of the successful British victory over General George Washington and the Continental Army at the Battle of Long Island on August 27, 1776, but warned them that, “notwithstanding the fair prospect, it was necessary to prepare for another campaign.” Somehow, the king had the idea that there was still hope to keep the colonies.

Despite George III’s harsh words, General William Howe and his brother, Admiral Richard Howe, still hoped to convince the Americans to rejoin the British empire in the wake of the colonists’ humiliating defeat at the Battle of Long Island. They hoped to do  thing peacefully, but that was just not to be. The British could easily have prevented Washington’s retreat from Long Island and captured most of the Patriot officer corps, including the commander in chief. However, instead of forcing the former colonies into submission by executing Washington and his officers as traitors, the Howe brothers let them go with the hope of swaying Patriot opinion towards a return to the mother country. The Howe brothers’ attempts at negotiation failed, and the War for Independence dragged on for another four years, until the formal surrender of the British to the Americans on October 19, 1781, after the Battle of Yorktown. The freedom of the United States was not going to be taken from them…and that was a serious embarrassment to Britain.

thing peacefully, but that was just not to be. The British could easily have prevented Washington’s retreat from Long Island and captured most of the Patriot officer corps, including the commander in chief. However, instead of forcing the former colonies into submission by executing Washington and his officers as traitors, the Howe brothers let them go with the hope of swaying Patriot opinion towards a return to the mother country. The Howe brothers’ attempts at negotiation failed, and the War for Independence dragged on for another four years, until the formal surrender of the British to the Americans on October 19, 1781, after the Battle of Yorktown. The freedom of the United States was not going to be taken from them…and that was a serious embarrassment to Britain.

When we think of our nation’s early wars, and really, up until the Persian Gulf War, soldiers were officially men only. Prior to the Persian Gulf War, any women who were in combat were disguised as men, or they were in non-combat roles, such as support staff and nurses. Few women were recognized for their service, much less honored for it, but on March 12, 1776, in Baltimore, Maryland, someone decided to change the way we looked at the effort made by women in wars. And when I say effort know that I include much sacrifice.

When we think of our nation’s early wars, and really, up until the Persian Gulf War, soldiers were officially men only. Prior to the Persian Gulf War, any women who were in combat were disguised as men, or they were in non-combat roles, such as support staff and nurses. Few women were recognized for their service, much less honored for it, but on March 12, 1776, in Baltimore, Maryland, someone decided to change the way we looked at the effort made by women in wars. And when I say effort know that I include much sacrifice.

That day, a public notice appeared in local papers recognizing the sacrifice of women to the cause of the revolution. The notice urged others to recognize women’s contributions as well, and announced, “The necessity of taking all imaginable care of those who may happen to be wounded in the country’s cause, urges us to address our humane ladies, to lend us their kind assistance in furnishing us with linen rags and old sheeting, for bandages.” On and off the battlefield, women were known to support the revolutionary cause by providing nursing assistance. But donating bandages and sometimes applying them was only one form of aid provided by the women of the new United States. From the earliest protests against British taxation, women’s assent and labor  was critical to the success of the cause. The boycotts that united the colonies against British taxation required female participation far more than male participation, in fact, the men designing the non-importation agreements chose to boycott products used mostly by women…how thoughtful of them!!

was critical to the success of the cause. The boycotts that united the colonies against British taxation required female participation far more than male participation, in fact, the men designing the non-importation agreements chose to boycott products used mostly by women…how thoughtful of them!!

Tea and cloth are perhaps the best examples of these boycotted products. While most schoolchildren have read of the men who dressed as Mohawk Indians and dumped large volumes of tea into Boston Harbor at the Boston Tea Party, as a form of opposition to the hated Tea Act, few realize that women…not men…drank most of the tea in colonial America. Samuel Adams and his friends may have dumped the tea in the harbor, but they were far more likely to drink rum than tea when they returned to their homes. Conveniently, their actions actually deprived their wives, mothers, sisters and daughters, and not themselves. The colonists only resorted to an attempted boycott of rum in 1774, after Britain had closed the port of Boston. I guess it was time for drastic measures.

Similarly, when John Adams and other men in power thought it best to stop importing fine British fabrics with  which to make their clothing during the protests of the late 1760s, it had little impact on their daily lives. Wearing homespun cloth may not have been as comfortable nor look as refined as their regular clothing, but it was Abigail and other colonial wives and homemakers, not John and his fellow men, who were forced to spend hours spinning clothes to create their families’ wardrobes. Thus, in 1776, when Abigail begged John to remember the ladies while drafting the U.S. Constitution, she was not begging a favor, but demanding payment of an enduring debt. And her husband, in good conscience could not deny her right, or her important request.

which to make their clothing during the protests of the late 1760s, it had little impact on their daily lives. Wearing homespun cloth may not have been as comfortable nor look as refined as their regular clothing, but it was Abigail and other colonial wives and homemakers, not John and his fellow men, who were forced to spend hours spinning clothes to create their families’ wardrobes. Thus, in 1776, when Abigail begged John to remember the ladies while drafting the U.S. Constitution, she was not begging a favor, but demanding payment of an enduring debt. And her husband, in good conscience could not deny her right, or her important request.

Most people think that English came from England, and of course, it did, however, in England prior to the 19th century, the English language was not spoken by the aristocracy, but rather only by “commoners.” Back then, English used to belong to the people, and I suppose that might explain some of the “incorrect” uses of the language which have been so severely attacked by contemporary English speakers. Prior to the 19th century, the aristocracy in English courts spoke French. This was due to the Norman Invasion of 1066 and caused years of division between the “gentlemen” who had adopted the Anglo-Norman French and those who only spoke English. Even the famed King Richard the Lionheart was actually primarily referred to in French, as Richard “Coeur de Lion.”

Most people think that English came from England, and of course, it did, however, in England prior to the 19th century, the English language was not spoken by the aristocracy, but rather only by “commoners.” Back then, English used to belong to the people, and I suppose that might explain some of the “incorrect” uses of the language which have been so severely attacked by contemporary English speakers. Prior to the 19th century, the aristocracy in English courts spoke French. This was due to the Norman Invasion of 1066 and caused years of division between the “gentlemen” who had adopted the Anglo-Norman French and those who only spoke English. Even the famed King Richard the Lionheart was actually primarily referred to in French, as Richard “Coeur de Lion.”

In my opinion, this dual language society would have caused numerous problems. The indication I get is that neither side could speak the language of the other, but I don’t know how a monarchy could rule, if the “commoners” could not understand the language and therefore the orders of the monarchy. French was spoken and learned by anyone in the upper  classes. However, it became less useful as English lost its control of various places in France, where the peasants spoke French, too. After that…about, 1450…English was simply more useful for talking to anybody. It is still true that British royals and many nobles are fluent in French, but they only use it to talk to French people, just like everybody else.

classes. However, it became less useful as English lost its control of various places in France, where the peasants spoke French, too. After that…about, 1450…English was simply more useful for talking to anybody. It is still true that British royals and many nobles are fluent in French, but they only use it to talk to French people, just like everybody else.

To further confuse your preconceptions about the English language, the “British accent” was, in reality, created after the Revolutionary War, meaning contemporary Americans sound more like the colonists and British soldiers of the 18th century than contemporary Brits. Many people have made a point of how much they love the British accent, but I think very few people know the real story behind the British accent. In the 18th century and before, the British “accent” was the way we speak herein America. Of course, accents vary greatly  by region, as we have seen with the accents of the south and east in the United States, but the “BBC English” or public school English accent…which sounds like the James Bond movies…didn’t come about until the 19th century and was originally adopted by people who wanted to sound fancier. I suppose it was like the aristocracy and the commoners, in that one group didn’t want to be mistaken for the other. After being handily defeated by the American colonists, I’m sure that the British were looking for a way to seem superior, even in defeat. The change in the accent of the English language was sufficient to make that distinction. Maybe it was their way of saying that they were better than the American guerilla-type soldiers who beat them in combat…basically they might have lost, but they were superior…even if it was only in how they sounded.

by region, as we have seen with the accents of the south and east in the United States, but the “BBC English” or public school English accent…which sounds like the James Bond movies…didn’t come about until the 19th century and was originally adopted by people who wanted to sound fancier. I suppose it was like the aristocracy and the commoners, in that one group didn’t want to be mistaken for the other. After being handily defeated by the American colonists, I’m sure that the British were looking for a way to seem superior, even in defeat. The change in the accent of the English language was sufficient to make that distinction. Maybe it was their way of saying that they were better than the American guerilla-type soldiers who beat them in combat…basically they might have lost, but they were superior…even if it was only in how they sounded.

As with any war, there are opinions that are polar opposites from each other. After all, if they all agreed, there would be no need for war. The Revolutionary War was no different. Yes, the British wanted to keep the United States as colonies belonging to the crown, but the people of the United States would have none of it…well, most of the people anyway. It seems shocking to us now, to think that there would be people in the United States who would want us to remain under Britain’s rule, but in fact, there were. They were known as the Loyalists, and they set about doing whatever they could to cause the United States to lose the Revolutionary War.

As with any war, there are opinions that are polar opposites from each other. After all, if they all agreed, there would be no need for war. The Revolutionary War was no different. Yes, the British wanted to keep the United States as colonies belonging to the crown, but the people of the United States would have none of it…well, most of the people anyway. It seems shocking to us now, to think that there would be people in the United States who would want us to remain under Britain’s rule, but in fact, there were. They were known as the Loyalists, and they set about doing whatever they could to cause the United States to lose the Revolutionary War.

Patriot, Lieutenant Colonel Francis “The Swamp Fox” Marion was fresh from a victory at Nelson’s Ferry on the Santee River in South Carolina on August 20, 1780. Marion, who was just five feet tall, won fame and the “Swamp Fox” nickname for his ability to strike and then quickly retreat into the South Carolina swamps without a trace. Marion used irregular methods of warfare and is considered  one of the fathers of modern guerrilla warfare and maneuver warfare, and is credited in the lineage of the United States Army Rangers. After the victory at Nelson’s Ferry, Marion and 52 of his militiamen rode east in order to escape the pursuing British Loyalists. They were successful, but during their escape, a second and much larger, force of Loyalists led by Major Micajah Ganey, attacked the militia from the northeast. Marion’s advance guard, led by Major John James, defeated Ganey’s advance guard and Marion ambushed the rest, causing Ganey’s main body of 200 Loyalists to flee in panic. The success of Marion’s militia broke the Loyalist stronghold on South Carolina east of the PeeDee River and attracted another 60 volunteers to the Patriot cause.

one of the fathers of modern guerrilla warfare and maneuver warfare, and is credited in the lineage of the United States Army Rangers. After the victory at Nelson’s Ferry, Marion and 52 of his militiamen rode east in order to escape the pursuing British Loyalists. They were successful, but during their escape, a second and much larger, force of Loyalists led by Major Micajah Ganey, attacked the militia from the northeast. Marion’s advance guard, led by Major John James, defeated Ganey’s advance guard and Marion ambushed the rest, causing Ganey’s main body of 200 Loyalists to flee in panic. The success of Marion’s militia broke the Loyalist stronghold on South Carolina east of the PeeDee River and attracted another 60 volunteers to the Patriot cause.

Marion rarely committed his men to frontal warfare, which was much more risky, but repeatedly surprised larger bodies of Loyalists or British regulars with quick surprise attacks and equally quick withdrawal from the  field. He was considered almost a ghost. Marion had previously earned fame as the only senior Continental officer in the area to escape the British following the fall of Charleston on May 12, 1780. His military strategy, while odd for the time, was really advanced for the time, and similar to some of today’s strategies. Marion took over the South Carolina militia force, first assembled by Thomas Sumter in 1780. Sumter returned home to bring Carolina Loyalists’ style terror tactics on the Loyalists who burned his plantation. After being wounded, Sumter withdrew from active fighting. Marion replaced him and teamed up with Major General Nathaniel Greene, who arrived in the Carolinas to lead the Continental forces in October 1780. Together, they are credited with pulling a Patriot victory from the jaws of defeat in the southern states.

field. He was considered almost a ghost. Marion had previously earned fame as the only senior Continental officer in the area to escape the British following the fall of Charleston on May 12, 1780. His military strategy, while odd for the time, was really advanced for the time, and similar to some of today’s strategies. Marion took over the South Carolina militia force, first assembled by Thomas Sumter in 1780. Sumter returned home to bring Carolina Loyalists’ style terror tactics on the Loyalists who burned his plantation. After being wounded, Sumter withdrew from active fighting. Marion replaced him and teamed up with Major General Nathaniel Greene, who arrived in the Carolinas to lead the Continental forces in October 1780. Together, they are credited with pulling a Patriot victory from the jaws of defeat in the southern states.

After the Revolutionary War, and the United States independence that followed, the relationship between the two nations was quite strained. The United States did not like having British military posts on our northern and western borders, and Britain’s violation of American neutrality in 1794 when the Royal Navy seized American ships in the West Indies during England’s war with France. Finally, in an attempt to smooth things over, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Jay, who was appointed by President Washington, came up with a treaty. The treaty officially known as the “Treaty of Amity Commerce and Navigation, between His Britannic Majesty; and The United States of America” was signed by Britain’s King George III on November 19, 1794 in London. However, after Jay returned home with news of the treaty’s signing, President Washington, who was now in his second term, had encountered fierce Congressional opposition to the treaty. By 1795, its ratification was still uncertain, and there was work to be done to change things.

After the Revolutionary War, and the United States independence that followed, the relationship between the two nations was quite strained. The United States did not like having British military posts on our northern and western borders, and Britain’s violation of American neutrality in 1794 when the Royal Navy seized American ships in the West Indies during England’s war with France. Finally, in an attempt to smooth things over, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Jay, who was appointed by President Washington, came up with a treaty. The treaty officially known as the “Treaty of Amity Commerce and Navigation, between His Britannic Majesty; and The United States of America” was signed by Britain’s King George III on November 19, 1794 in London. However, after Jay returned home with news of the treaty’s signing, President Washington, who was now in his second term, had encountered fierce Congressional opposition to the treaty. By 1795, its ratification was still uncertain, and there was work to be done to change things.

The two biggest opponents to the treaty were two future presidents…Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Jefferson was, at the time, in between political positions. He had just completed a term as Washington’s secretary of state from 1789 to 1793 and had not yet become John Adams’ vice president. Fellow Virginian, James Madison was a member of the House of Representatives. Jefferson, Madison and other opponents feared the treaty gave too many concessions to the British. They argued that Jay’s negotiations actually weakened American trade rights and complained that it committed the United States to paying pre-revolutionary debts to English merchants. Washington himself was not completely satisfied with the treaty, but considered preventing another war with America’s former colonial master a priority.

The treaty was finally approved by Congress on August 14, 1795, with exactly the two-thirds majority it needed

to pass. President Washington signed the treaty just four days later, on August 18, 1795. Washington and Jay may have won the legislative battle and averted war temporarily, but it created a conflict at home that highlighted a deepening division between those of different political ideologies in Washington DC, much like what we see these days. Jefferson and Madison mistrusted Washington’s attachment to maintaining friendly relations with England over revolutionary France, who would have welcomed the United States as a partner in an expanded war against England.

to pass. President Washington signed the treaty just four days later, on August 18, 1795. Washington and Jay may have won the legislative battle and averted war temporarily, but it created a conflict at home that highlighted a deepening division between those of different political ideologies in Washington DC, much like what we see these days. Jefferson and Madison mistrusted Washington’s attachment to maintaining friendly relations with England over revolutionary France, who would have welcomed the United States as a partner in an expanded war against England.

When we think of the Revolutionary war, or any other war, the people we think of are usually generals, presidents, and enemies, but in the case of the Revolutionary War, there is another name that is quite important. Her name was Betsy Ross. She became a patriotic icon in the late 19th century when stories surfaced that she had sewn the first “stars and stripes” US flag in 1776. Some say that story is doubtful, but Ross was known to have sewn flags during the Revolutionary War. Betsy was born Elizabeth Griscom on January 1, 1752, to Rebecca James Griscom and Samuel Griscom, who were both Quakers, living in the bustling colonial city of Philadelphia. As was often the case in those days, families were large, and Elizabeth was the eighth of seventeen children. Elizabeth came from generations of craftsman. Her father was a house carpenter. Elizabeth attended a Quaker school and was then apprenticed to William Webster, who was an upholsterer. In Webster’s workshop she learned to sew mattresses, chair covers and window blinds, but Betsy was a bit of a rebel, it seems. In the summer of 1773, when Betsy was 21 years old, she crossed the river to New Jersey to elope with John Ross, a fellow apprentice of Webster’s and the son of an Episcopal minister. This was a double act of defiance, and she was expelled from the Quaker church. The Rosses started their own upholstery shop, and John joined the militia. He died after barely two years of marriage. Family legend attributed John’s death to a gunpowder explosion, but illness is a more likely cause of death. Whatever the cause, Betsy found herself widowed, and exiled from her family, but Betsy was no quitter.

When we think of the Revolutionary war, or any other war, the people we think of are usually generals, presidents, and enemies, but in the case of the Revolutionary War, there is another name that is quite important. Her name was Betsy Ross. She became a patriotic icon in the late 19th century when stories surfaced that she had sewn the first “stars and stripes” US flag in 1776. Some say that story is doubtful, but Ross was known to have sewn flags during the Revolutionary War. Betsy was born Elizabeth Griscom on January 1, 1752, to Rebecca James Griscom and Samuel Griscom, who were both Quakers, living in the bustling colonial city of Philadelphia. As was often the case in those days, families were large, and Elizabeth was the eighth of seventeen children. Elizabeth came from generations of craftsman. Her father was a house carpenter. Elizabeth attended a Quaker school and was then apprenticed to William Webster, who was an upholsterer. In Webster’s workshop she learned to sew mattresses, chair covers and window blinds, but Betsy was a bit of a rebel, it seems. In the summer of 1773, when Betsy was 21 years old, she crossed the river to New Jersey to elope with John Ross, a fellow apprentice of Webster’s and the son of an Episcopal minister. This was a double act of defiance, and she was expelled from the Quaker church. The Rosses started their own upholstery shop, and John joined the militia. He died after barely two years of marriage. Family legend attributed John’s death to a gunpowder explosion, but illness is a more likely cause of death. Whatever the cause, Betsy found herself widowed, and exiled from her family, but Betsy was no quitter.

In the summer of 1776 or 1777, a widowed Betsy Ross received a visit from General George Washington regarding a design for a flag for the new nation. Washington and the Continental Congress had come up with the basic layout. Betsy allegedly finalized the design, arguing for stars with five points, instead of the six  pointed stars that Washington had suggested, mainly because the cloth could be folded and cut out with a single snip. The tale of Washington’s visit to Ross was first made public in 1870, nearly a century later, by Betsy Ross’s grandson. However, the flag’s design was apparently not fixed until later than 1776 or 1777. Charles Wilson Peale’s 1779 painting of George Washington following the 1777 Battle of Princeton features a flag with six-pointed stars.

pointed stars that Washington had suggested, mainly because the cloth could be folded and cut out with a single snip. The tale of Washington’s visit to Ross was first made public in 1870, nearly a century later, by Betsy Ross’s grandson. However, the flag’s design was apparently not fixed until later than 1776 or 1777. Charles Wilson Peale’s 1779 painting of George Washington following the 1777 Battle of Princeton features a flag with six-pointed stars.

As I said, there has been some arguments as to the validity of Betsy Ross’ claim to fame as the flag’s maker, but most have been successfully disproven. Still, the fact that a painting was done with the six pointed stars is something to consider, or at least wonder about, not that I’m disputing her claim to fame. In fact, I have wondered if the painting was done that way, because of General Washington’s plan for the flag. I have also wondered why it was always said that Betsy Ross sewed the flag, because in June of 1777, Betsy remarried, to a man named Joseph Ashburn, who was a sailor. They went on to have two daughters. In 1782 Ashburn was apprehended while working as a privateer in the West Indies and died in a British prison. A year later, Betsy married John Claypoole, a man who had grown up with her in Philadelphia’s Quaker community and had been imprisoned in England with Ashburn. A few months after their wedding, the Treaty of Paris was signed, ending the Revolutionary War. They went on to have five daughters. Over the next decades, Betsy Claypoole and her daughters sewed upholstery and made flags, banners and standards for the new nation. In 1810 she made six 18 by 24 foot garrison flags to be sent to New Orleans. The next year she made 27 flags for the Indian Department. She spent her last decade in retirement, her vision failing. She died in 1836, at age 84.

The records of the US flag’s origins are not complete, in part because at that time Americans were indifferent to  flags as national relics. “The Star-Spangled Banner” was written in 1812, but wasn’t popular until the 1840s. As the 1876 US Centennial approached, enthusiasm for the flag increased. In 1870, that Betsy Claypoole’s grandson William Canby presented the family story to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. At the time several claims on the first flag were surfacing, ranging from other Philadelphia seamstresses to a New Hampshire quilting bee said to have fashioned the banner out of cut-up gowns. Most such stories were wishful desires to be symbols of female Revolutionary patriotism. To be women materially supporting their fighting men and, maybe to show George Washington a better way to make a star. Nevertheless, none of the stories ever took hold, except the one about Betsy Ross…or Ashburn…or Claypoole.

flags as national relics. “The Star-Spangled Banner” was written in 1812, but wasn’t popular until the 1840s. As the 1876 US Centennial approached, enthusiasm for the flag increased. In 1870, that Betsy Claypoole’s grandson William Canby presented the family story to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. At the time several claims on the first flag were surfacing, ranging from other Philadelphia seamstresses to a New Hampshire quilting bee said to have fashioned the banner out of cut-up gowns. Most such stories were wishful desires to be symbols of female Revolutionary patriotism. To be women materially supporting their fighting men and, maybe to show George Washington a better way to make a star. Nevertheless, none of the stories ever took hold, except the one about Betsy Ross…or Ashburn…or Claypoole.

When I think of Independence Day, I often think about how the fireworks remind me of the many battles that went on in order to win our freedom. Then, I began to wonder if there was ever a time when the 13 colonies almost didn’t become the United States. Britain was, after all, the world’s greatest superpower at the time. British soldiers fought on 5 continents and they had an amazing navy. They massacred rebels and civilians in Jamaica and India around the same time and retained those colonies. So, why not the 13 colonies of North America? There are many explanations, but the one I found most interesting seems, almost to tie to the way things are in America right now…and really all along.

When I think of Independence Day, I often think about how the fireworks remind me of the many battles that went on in order to win our freedom. Then, I began to wonder if there was ever a time when the 13 colonies almost didn’t become the United States. Britain was, after all, the world’s greatest superpower at the time. British soldiers fought on 5 continents and they had an amazing navy. They massacred rebels and civilians in Jamaica and India around the same time and retained those colonies. So, why not the 13 colonies of North America? There are many explanations, but the one I found most interesting seems, almost to tie to the way things are in America right now…and really all along.

The reality is that Britain won many times on the battlefield, but…lost in the taverns. The taverns, you say. How  could that be? Well, taverns were everywhere. They were the social network of colonial life, much like the town hall meetings, and even more, like Facebook or Twitter today. Some areas of Massachusetts and Pennsylvania had taverns every few miles. People could get their mail there, hire a worker, talk to friends, sell crops, buy land, and eat a good meal. It was in these places that opinions were formed. People discussed the problems they had with British rule, and talked about how to get rid of the yoke of the Mother country.

could that be? Well, taverns were everywhere. They were the social network of colonial life, much like the town hall meetings, and even more, like Facebook or Twitter today. Some areas of Massachusetts and Pennsylvania had taverns every few miles. People could get their mail there, hire a worker, talk to friends, sell crops, buy land, and eat a good meal. It was in these places that opinions were formed. People discussed the problems they had with British rule, and talked about how to get rid of the yoke of the Mother country.

Some say that Britain might have had a chance if they had been represented in the taverns too, but I don’t think so. The time had come for Americans to think for themselves, and to run their own lives and their own country. First came the Stamp Act and the Americans protested. More oppression followed, as did the protests.  The resistance grew and grew, until war broke out. No matter what it took, the colonies were determined not to lose. The tavern meetings had accomplished what they needed to. No matter how many times it looked like Britain might win, they would not, because of…well, social networking. Social networking, when people get together to discuss right from wrong, and to discuss solutions. Sometimes the solutions are simple, and other times they create enough of a stir to bring about a revolution. No matter what the reason, the colonies were not about to lose, and because of that, we are a free nation and it was on this day, July 4, 1776 that our independence was made a reality, and we became the land of the free and the home of the brave. Happy Independence Day America!!

The resistance grew and grew, until war broke out. No matter what it took, the colonies were determined not to lose. The tavern meetings had accomplished what they needed to. No matter how many times it looked like Britain might win, they would not, because of…well, social networking. Social networking, when people get together to discuss right from wrong, and to discuss solutions. Sometimes the solutions are simple, and other times they create enough of a stir to bring about a revolution. No matter what the reason, the colonies were not about to lose, and because of that, we are a free nation and it was on this day, July 4, 1776 that our independence was made a reality, and we became the land of the free and the home of the brave. Happy Independence Day America!!

Have you ever wondered why US money is green…or mostly green, while the money of so many other countries is very colorful? How did paper money come about anyway? Actually, paper money has been around in the United States since the beginning, off and on anyway. Printing paper money has been a controversial practice over the years. In 1861, as a means of financing the American Civil War, the federal government began issuing paper money for the first time since the Continental Congress printed currency to help pay for the Revolutionary War. The earlier form of paper dollars, dubbed continentals, were produced in such high volume that they soon lost much of their value. Devaluing our money has been a long standing problem with paper money. It’s simply too easy to print more money than we have gold to back.

Have you ever wondered why US money is green…or mostly green, while the money of so many other countries is very colorful? How did paper money come about anyway? Actually, paper money has been around in the United States since the beginning, off and on anyway. Printing paper money has been a controversial practice over the years. In 1861, as a means of financing the American Civil War, the federal government began issuing paper money for the first time since the Continental Congress printed currency to help pay for the Revolutionary War. The earlier form of paper dollars, dubbed continentals, were produced in such high volume that they soon lost much of their value. Devaluing our money has been a long standing problem with paper money. It’s simply too easy to print more money than we have gold to back.

In the decades before the Civil War, private, state chartered banks printed the paper money. Not surprisingly, this resulted in a wide variety of denominations and designs. Apparently, there was no real decision on how this should look. I guess they weren’t really worried about counterfeiting at that time. The bills that came out in the 1860s became known as greenbacks, because their backsides were printed in green ink. This ink was used as an anti-counterfeiting measure used to prevent photographic knockoffs, since the cameras of the time could only take pictures in black and white. I guess that counterfeiting had become a problem in the earlier years after all. And as we all know, the new scanners continue to improve the possibility of counterfeiting, making watermarks and security strips necessary too. And they have also added color to the money these days.

In 1929, the federal government decided that the paper money was too expensive to print, so in an effort to cut costs, they shrunk the size of all paper money. At the same time, they standardized the designs for each denomination, which made it easier for people to tell the difference between real and counterfeit bills. The new, more compact bills continued to be printed in green ink, because according to the US Bureau of Printing and Engraving, the ink was readily available and durable. They also thought that the color green represented stability. Today, there is some $1.2 trillion in coins and paper money in circulation in America. It costs about 5 cents to produce every $1 bill and around 13 cents to make a $100 bill, the highest denomination currently in

circulation. Don’t ask me why the difference, I would have expected them to be pretty much the same cost to manufacture. The estimated life span of a $1 bill is close to six years, while a $100 bill typically lasts 15 years, which makes sense to me, because we don’t use the $100 bill nearly as much. The $50 bill has the shortest average life span, at 3.7 years, and I would have expected the shortest lifespan to be the $1 bill, because we us those all the time.

circulation. Don’t ask me why the difference, I would have expected them to be pretty much the same cost to manufacture. The estimated life span of a $1 bill is close to six years, while a $100 bill typically lasts 15 years, which makes sense to me, because we don’t use the $100 bill nearly as much. The $50 bill has the shortest average life span, at 3.7 years, and I would have expected the shortest lifespan to be the $1 bill, because we us those all the time.

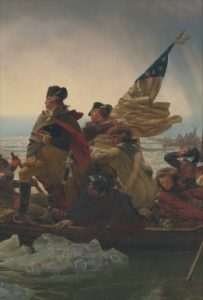

The year was 1776, and it was Christmas Day, but for the men with George Washington, it was not a day of celebration…not exactly anyway. They were in the middle of fighting a war, and the fighting didn’t just stop because it was Christmas, not this year anyway. This was to be an unusual Christmas as far as wartime Christmases went. In 1776, it was difficult to fight a war in the wintertime, because the slower modes of travel. Most times in a war, the armies took the Winter off from warring, but this army was not laying up for the Winter. This war would continue on…no matter what the weather was like.

The year was 1776, and it was Christmas Day, but for the men with George Washington, it was not a day of celebration…not exactly anyway. They were in the middle of fighting a war, and the fighting didn’t just stop because it was Christmas, not this year anyway. This was to be an unusual Christmas as far as wartime Christmases went. In 1776, it was difficult to fight a war in the wintertime, because the slower modes of travel. Most times in a war, the armies took the Winter off from warring, but this army was not laying up for the Winter. This war would continue on…no matter what the weather was like.

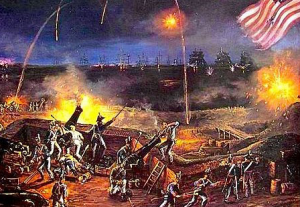

Things looked bad that year. The Continental Army had suffered a series of defeats in their battle against the British oppression. After some successful maneuvers, Colonel Henry Knox came to the attention of General George Washington who worked to place him in overall command to the Continental Army. Under his command, the Continentals brought 18 cannon over the river…3  Pounders, 4 Pounders, some 6 Pounders, horses to pull the carriages, and enough ammunition for the coming battle. The 6 Pounders, weighing as much as 1,750 pounds were the most difficult to transport to the far side of the river. But in the end all the trouble of moving this large artillery train to Trenton proved its worth. Knox would place the bulk of his artillery at the top of the town where its fire commanded the center of Trenton.

Pounders, 4 Pounders, some 6 Pounders, horses to pull the carriages, and enough ammunition for the coming battle. The 6 Pounders, weighing as much as 1,750 pounds were the most difficult to transport to the far side of the river. But in the end all the trouble of moving this large artillery train to Trenton proved its worth. Knox would place the bulk of his artillery at the top of the town where its fire commanded the center of Trenton.

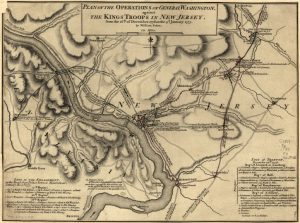

The plan devised by Knox and Washington was to conduct a surprise attack upon a Hessian garrison of roughly 1,400 soldiers located in and around Trenton, New Jersey. Washington hoped that a quick victory at Trenton would bolster sagging morale in his army and encourage more men to join the ranks of the Continentals in the coming new year. After several councils of war, General George Washington set the date for the river crossing for Christmas night 1776. It was an unprecedented plan, because the expectation was always that the armies would hold up somewhere for the winter. No one had attacked in winter before, and especially on Christmas. George Washington led 2,400 troops on a daring nighttime crossing of the icy Delaware River. Stealing into New Jersey, on December 26 the Continental forces launched the surprise attack on Trenton.

The gamble paid off. Many of the Hessians were still disoriented from the previous night’s holiday bender, and colonial forces defeated them with minimal bloodshed. While Washington had pulled off a shock victory, his army was unequipped to hold the city and he was forced to re-cross the Delaware that same day…with nearly 1,000 Hessian prisoners in tow. Washington would go on to score successive victories at the Battles of the Assunpink Creek and Princeton, and his audacious crossing of the frozen Delaware served as a crucial rallying cry for the beleaguered Continental Army. The Revolutionary War would be won by the Continental Army of course, and the rules of warfare changed forever.

The gamble paid off. Many of the Hessians were still disoriented from the previous night’s holiday bender, and colonial forces defeated them with minimal bloodshed. While Washington had pulled off a shock victory, his army was unequipped to hold the city and he was forced to re-cross the Delaware that same day…with nearly 1,000 Hessian prisoners in tow. Washington would go on to score successive victories at the Battles of the Assunpink Creek and Princeton, and his audacious crossing of the frozen Delaware served as a crucial rallying cry for the beleaguered Continental Army. The Revolutionary War would be won by the Continental Army of course, and the rules of warfare changed forever.