oregon trail

It was inevitable really…the migration of the people of the United States to the west coast, in search of gold, adventure, and more land. The east was filling up, and there was no place else to go, but west. Of course, many people would either not make it all the way to the West; choosing rather to homestead along the way, die, or actually make it to the West, and then return to the East. Nevertheless, before anyone could find out is life on the west coast suited them or not, they had to get to the west coast, and on May 16, 1842, the first major wagon train to the northwest departed from Elm Grove. Missouri, on the Oregon Trail. This was a little bit of a risky move, because US sovereignty over the Oregon Territory was not clearly established until 1846.

It was inevitable really…the migration of the people of the United States to the west coast, in search of gold, adventure, and more land. The east was filling up, and there was no place else to go, but west. Of course, many people would either not make it all the way to the West; choosing rather to homestead along the way, die, or actually make it to the West, and then return to the East. Nevertheless, before anyone could find out is life on the west coast suited them or not, they had to get to the west coast, and on May 16, 1842, the first major wagon train to the northwest departed from Elm Grove. Missouri, on the Oregon Trail. This was a little bit of a risky move, because US sovereignty over the Oregon Territory was not clearly established until 1846.

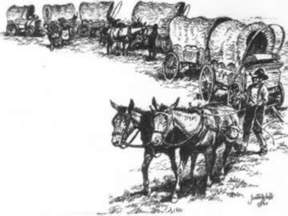

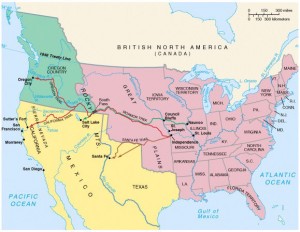

Nevertheless, American fur trappers and missionary groups had been living in the region for decades, along with Indians who had settled the land centuries earlier. Of course, everyone out there had a story to tell, and there were dozens of books and lectures that proclaimed Oregon’s agricultural potential. You can’t tell a story without creating interest somewhere. Even a boring story is of interest to someone, and this was no boring story. With the books and lectures coming out of the West, the white American farmers were very interested. They saw a chance to make their fortune, or at least to become independent. The actual first overland immigrants to Oregon, intended to farm primarily. A small band of 70 pioneers left Independence, Missouri in 1841. The stories they had heard from the fur traders brought them along the same route the traders had blazed, taking them west along the Platte River through the Rocky Mountains via the easy South Pass in Wyoming and then northwest to the Columbia River…basically through some on my own stomping grounds. Eventually, the trail they took was renamed by the pioneers, who called it the Oregon Trail.

The migration, once started, had little chance of being stopped, and in 1842, a slightly larger group of 100 pioneers made the 2,000-mile journey to Oregon. With the success of these two groups, the inevitable happened, accelerated in a major way by the severe depression in the Midwest, combined with a flood of propaganda from fur traders, missionaries, and government officials extolling the virtues of the land. They may have had good intentions, but it is never a good idea to lie to the public. With the disinformation on their minds, farmers dissatisfied with their prospects in Ohio, Illinois, Kentucky, and Tennessee, hoped to find better lives in the supposed paradise of Oregon. With that another type of “rush” began. Much like the “gold rush” years, the farmers saw the land as their “gold” and headed west.

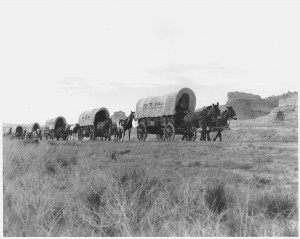

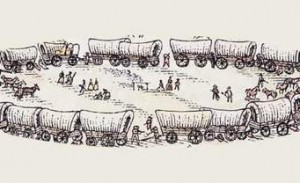

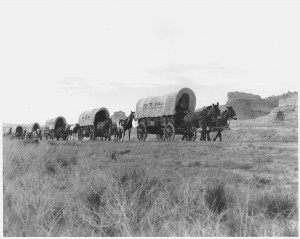

So, on this day in 1843, approximately 1,000 men, women, and children climbed aboard their wagons and steered their horses west out of the small town of Elm Grove, Missouri. It was the first real wagon train, comprised of more than 100 wagons with a herd of 5,000 oxen and cattle trailing behind. The train was led by Dr Elijah White, a Presbyterian missionary who had made the trip the year before. At first the trail was fairly easy, traveling over the flat lands of the Great Plains. There weren’t many obstacles in that area, and few river crossings, some of which could be dangerous for wagons. The bigger risk in the early days was the danger of Indian attacks, but they were still few and far between…at first anyway. The wagons were drawn into a circle at night to give the pioneers better protection from any attack that might come. They were very afraid of the Indians, who were enough different that they seemed deadly…to the pioneers anyway, and the Indians fear the White Man because of their weapons, and they were angry because the White Man wanted the land. In reality, the pioneers were far more in danger from seemingly mundane causes, like the accidental discharge of firearms, falling off mules or horses, drowning in river crossings, and disease. The trail became much more difficult, with steep ascents and descents over rocky terrain, after the train entered the mountains. The pioneers risked injury from overturned and runaway wagons.

Nevertheless, the wagon trains persevered, and the migrant movement continued until the West was populated. As for the 1,000-person party that made that original journey way back in 1843…the vast majority survived to reach their destination in the fertile, well-watered land of western Oregon. The next migration, in

1844 was smaller than that of the previous season, but in 1845 it jumped to nearly 3,000. Migration to the West was here to stay and the trains became an annual event, although the practice of traveling in giant convoys of wagons soon changed to many smaller bands of one or two-dozen wagons. The wagon trains really became a thing of the past in 1884, when the Union Pacific constructed a railway along the route.

1844 was smaller than that of the previous season, but in 1845 it jumped to nearly 3,000. Migration to the West was here to stay and the trains became an annual event, although the practice of traveling in giant convoys of wagons soon changed to many smaller bands of one or two-dozen wagons. The wagon trains really became a thing of the past in 1884, when the Union Pacific constructed a railway along the route.

I have lived in Wyoming since I was three years old, and so sometimes it’s easy for me to forget some of the places that have great historical value, but they are not as well known as some of the other places, like Yellowstone National Park. Register Cliff is one such landmark that I don’t often think about, although I have been there, and it really is a cool place.

I have lived in Wyoming since I was three years old, and so sometimes it’s easy for me to forget some of the places that have great historical value, but they are not as well known as some of the other places, like Yellowstone National Park. Register Cliff is one such landmark that I don’t often think about, although I have been there, and it really is a cool place.

Register Cliff is a sandstone cliff, that is located on the Oregon Trail. The cliff is a soft, chalky, limestone wall rising more than 100 feet above the North Platte River. When my sisters and I were kids, our parents would take us on trips, and point out every (and I mean every) Oregon Trail marker that we passed. In Wyoming, that is a lot of markers. As the emigrants made their way on the Oregon Trail, searching for a better life in the west, they came upon this cliff and chiseled the names of their families on the soft stones of the cliff. It was one of the key checkpoint landmarks for parties heading west along the Platte River valley west of Fort John, Wyoming which allowed  travelers to verify they were on the correct path up to South Pass and not moving into impassable mountain terrains. Geographically, it is on the eastern ascent of the Continental divide leading upward out of the great plains in the eastern part of Wyoming.

travelers to verify they were on the correct path up to South Pass and not moving into impassable mountain terrains. Geographically, it is on the eastern ascent of the Continental divide leading upward out of the great plains in the eastern part of Wyoming.

As more and more people “registered” on the cliff, word started to get around about this notable historic landmark. People quickly began to see the value of the cliff. Besides knowing that they were going the right direction, the emigrants realized that they were a part of history. Their names would forever be carved in the stone of the cliff, stating that they were among the brave people who moved to the west to settle the land.

The practice soon became the custom of the day, and the other northern Emigrant Trails that split off farther west such as the California Trail and Mormon Trail began to follow the custom too, inscribing their names on its  rocks during the western migrations of the 19th century. It is estimated that 500,000 emigrants used these trails from 1843–1869. Unfortunately, up to one-tenth of the emigrants died along the way, usually due to disease and other hazards. Nevertheless, those who made it this far were forever known to those who stop by. Register Cliff is the easternmost of the three prominent emigrant “recording areas” located within Wyoming. The other two are Independence Rock and Names Hill. The site was where emigrants camped on their first night west of Fort Laramie. The property was donated by Henry Frederick to the state of Wyoming, to be preserved. Register Cliff was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1969.

rocks during the western migrations of the 19th century. It is estimated that 500,000 emigrants used these trails from 1843–1869. Unfortunately, up to one-tenth of the emigrants died along the way, usually due to disease and other hazards. Nevertheless, those who made it this far were forever known to those who stop by. Register Cliff is the easternmost of the three prominent emigrant “recording areas” located within Wyoming. The other two are Independence Rock and Names Hill. The site was where emigrants camped on their first night west of Fort Laramie. The property was donated by Henry Frederick to the state of Wyoming, to be preserved. Register Cliff was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1969.

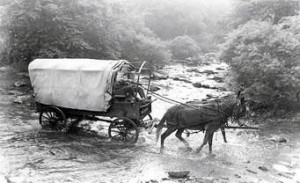

Trips across the United States in the mid-1800’s were slow and often treacherous. The trips were taken on wagons pulled by horses or oxen. It took months to get across the nation, and many people did not make it. Illness, Indian attacks, heat, cold, or animal bites, all served to cause problems, but one of the worse dangers was water. Of course, water could be bad and filled with bacteria, but more importantly, water, in the form of rivers could make crossing extremely dangerous and sometimes deadly. Rivers that were swift or deep, could mean the end for wagons, animals, and for people.

Trips across the United States in the mid-1800’s were slow and often treacherous. The trips were taken on wagons pulled by horses or oxen. It took months to get across the nation, and many people did not make it. Illness, Indian attacks, heat, cold, or animal bites, all served to cause problems, but one of the worse dangers was water. Of course, water could be bad and filled with bacteria, but more importantly, water, in the form of rivers could make crossing extremely dangerous and sometimes deadly. Rivers that were swift or deep, could mean the end for wagons, animals, and for people.

One such danger, located on the Oregon Trail, where emigrants made their way to Oregon, California, and Utah, was the North Platte River near present day Casper, Wyoming. In those days, there were many people looking to make a living in something besides the gold industry, which wasn’t always successful for the majority of people, so they set up things like commercial ferries to transport wagon trains across the treacherous rivers, like the North Platte River. It was a safer way to cross the rivers, to be sure, but it was also expensive, and so many people tried to cross on their own. Mostly due to their inexperience, many people lost everything trying to cross, sometimes even their lives. Many emigrants, unwilling to pay, tried to fashion their own “ferries,” with varying success. Until bridges were built, nearly all travelers swam their livestock across, and many people and animals drowned in the swift, deep, shockingly cold water of the Platte.

From present-day central Nebraska to South Pass in west-central Wyoming, emigrants to California, Oregon and Utah all took more or less one route. Most of the wagon trains came up the south side of the Platte from Fort Kearney. They crossed the South Platte in western Nebraska where the river forks, and continued west, going up the south side of the north fork. This route meant that they would have to ford the Laramie River where it joined the North Platte at Fort Laramie. Then, finally they could cross the North Platte itself 150 miles later, where the river turned to go to the south near present Casper. Once they made the treacherous North Platte River crossing, the travelers could continue on to the west. There was simply no other way to get there from the East at that time in history.

Routes changed periodically, including crossings at Red Buttes, west of Casper during fur-trade times in the  1820s and 1830s. Crossing points varied more and more during the mid-1840s, including along 25 miles of river from the mouth of Deer Creek, at present-day Glenrock, Wyoming to Casper, Wyoming. Many people crafted small boats by emptying their wagons, removing the wagon box from the running gear, caulking the boxes water tight with tar, dismantling the running gear into pieces, and then ferrying everything across the water in the wagon boxes. Wow!! What a long drawn out, time consuming way to build a boat. Them they used poles or oars for guidance and often using ox or human power to tow the craft across the water with long ropes. This was a fairly reliable method, as I said very slow due to the unloading, dismantling, and reloading.

1820s and 1830s. Crossing points varied more and more during the mid-1840s, including along 25 miles of river from the mouth of Deer Creek, at present-day Glenrock, Wyoming to Casper, Wyoming. Many people crafted small boats by emptying their wagons, removing the wagon box from the running gear, caulking the boxes water tight with tar, dismantling the running gear into pieces, and then ferrying everything across the water in the wagon boxes. Wow!! What a long drawn out, time consuming way to build a boat. Them they used poles or oars for guidance and often using ox or human power to tow the craft across the water with long ropes. This was a fairly reliable method, as I said very slow due to the unloading, dismantling, and reloading.

Emma Gatewood was a survivor. When I read the first few lines about her, I thought her story was remarkable, but as I read the whole story, I realized just how remarkable she really was. Emma’s married life was pure torture, with the exception of her children, whom she dearly loved. Emma married her husband, Perry Clayton Gatewood, a 26 year old school teacher, turned farmer, when she was just 19 years old. He was a horrible man, who immediately put her to work building fences, burning tobacco beds, and mixing cement, in addition to her household chores. Three months after their wedding, he started to beat her, a practice he continued until, one day in 1939, he broke her teeth, cracked one of her ribs and bloodied her face. Women didn’t have as many options back then, so Emma was stuck. Because Emma threw a sack of flour at him, the police came and arrested her, not him, and put her in jail. The next day, when the mayor saw her battered face, he took her to his own home, where she remained under his protection until she got back on her feet.

Emma Gatewood was a survivor. When I read the first few lines about her, I thought her story was remarkable, but as I read the whole story, I realized just how remarkable she really was. Emma’s married life was pure torture, with the exception of her children, whom she dearly loved. Emma married her husband, Perry Clayton Gatewood, a 26 year old school teacher, turned farmer, when she was just 19 years old. He was a horrible man, who immediately put her to work building fences, burning tobacco beds, and mixing cement, in addition to her household chores. Three months after their wedding, he started to beat her, a practice he continued until, one day in 1939, he broke her teeth, cracked one of her ribs and bloodied her face. Women didn’t have as many options back then, so Emma was stuck. Because Emma threw a sack of flour at him, the police came and arrested her, not him, and put her in jail. The next day, when the mayor saw her battered face, he took her to his own home, where she remained under his protection until she got back on her feet.

Emma and Perry had 11 children, and unfortunately, the treatment of their mother was not hidden from them. Nevertheless, the story of Emma’s abuse at the hands of her husband went untold for more than a 50 years. In 2014, a newspaper reporter named Ben Montgomery, Emma’s great grand nephew, told her story in his book, “Grandma Gatewood’s Walk.” Emma Rowena (Caldwell) Gatewood passed away on June 04, 1973 in Gallipolis, Ohio, of an apparent heart attack, at the grand old age of 85, having accomplished much since her birth on  October 25, 1887, in Gallia County, Ohio. Her father, Hugh Caldwell, a farmer, had lost a leg after being wounded in the Civil War and in his depression, turned to a life of drinking and gambling. Her mother, Evelyn (Trowbridge) Caldwell, raised the couple’s 15 children, who slept four to a bed in the family’s log cabin.

October 25, 1887, in Gallia County, Ohio. Her father, Hugh Caldwell, a farmer, had lost a leg after being wounded in the Civil War and in his depression, turned to a life of drinking and gambling. Her mother, Evelyn (Trowbridge) Caldwell, raised the couple’s 15 children, who slept four to a bed in the family’s log cabin.

In an interview with her children, Montgomery, who worked for The Tampa Bay Times in Florida. In his research for the book, her surviving children spoke with him and entrusted him with her journals, letters, and scrapbooks. In that material he found stark references to what she had withheld from news interviewers: that her husband had nearly pummeled her to death several times. During one beating, she wrote, he broke a broom over her head. Her children told Montgomery that their father’s sexual hunger had been insatiable and that he forced himself on their mother several times a day. He made their lives a nightmare for years.

The woods became a place of solace and safety for Emma, who would often escape to them amid her husband’s rants. She came to view the wilderness as protective and restorative. In 1937 she left him and moved in with relatives in California. She was forced to leave behind two daughters, ages 9 and 11, who were still at home. Emma knew her husband would not beat the girls, and she could not afford to take them with her. She wrote to the girls to explain it to them, making sure not to leave a return address. In the letter, she wrote, “I have suffered enough at his hands to last me for the next hundred years.” Nevertheless, Emma couldn’t stand to be away from her girls any longer, so she returned after a few months. Her life became a prison after that. Her husband would not let her out of his sight. She later wrote that in 1938, he beat her “beyond recognition” 10 times. “For a lot of people the trail is a refuge,” Brian B. King, a publisher of guidebooks and maps for the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, said in a telephone interview. “But seldom is it a refuge for something as bad  as that.” A short time later, her husband left for good, filed for divorce, which was granted in 1941, and he was out of her life.

as that.” A short time later, her husband left for good, filed for divorce, which was granted in 1941, and he was out of her life.

Emma’s hiking became a saving grace for her…she loved it. In 1949, she came across a National Geographic magazine article about the Appalachian Trail and became intrigued to learn in reading it that no woman had ever hiked it solo. In 1954, in her first attempt at hiking the Appalachian Trail, she started out in Maine, but broke her glasses, got lost, and was rescued by rangers, who told her to go home. Undaunted, she tried again in 1955, starting from Georgia this time. She was 67 years old, a mother of 11, a grandmother and even a great-grandmother when she became the first woman to hike the entire Appalachian Trail by herself in one season. She would go on to repeat the feat 2 more times. Soon everyone was calling her “America’s most celebrated pedestrian.” In 1959, Emma went on to conquer the 2,000 miles of the Oregon Trail, trekking alone from Independence, Missouri to Portland, Oregon.

My dad passed away on December 12, 2007, but since my mom was still alive, we never really went through his things…until after her passing on February 22, 2015. Mom had given out some of Dad’s things to different family members, but the bulk of his things would wait until her passing to be given to those who would receive them.

In his later years, my dad got cold often. That can happen as we age, or with surgeries to the chest or abdomen, which dad had to repair damage from Pancreatitis. More and more often, Dad could be seen wearing a sweater, and it really became a signature item for him. One sweater in particular that he wore almost daily, was a multi-shade blue striped sweater. He wore it so often, that it is one of the ways I picture him in my mind. I had asked Mom for that sweater shortly after Dad passed away, and was told I could have it, but did not receive it until now.

This was the sweater that Dad had on when he and Mom danced their last New Years Eve dance on January 1, 2007, just under a year before his passing. It was also the sweater he wore on his visits to the hospital when Mom was receiving Chemotherapy treatments for the Lymphoma Brain Tumor that she would beat in 2007. The blue sweater became synonymous of Dad…in my mind anyway.

There are many things that remind me of my dad. Anything World War II, of course, because I have written so much about his time in the war, and because we have toured the B-17s several times together, making the B-17 an integral part of my memories of my dad. Then, there are the funny memories of Dad, that always come to my mind…things like the whisker rub, our many debates, pretending to box with him, the Oregon Trail  markers, the many vacations, and of course, the swatting games he played with the grandkids, will always bring back great memories of my dad. All of those things bring images of my dad and what an amazing man he was, but they are not things I can hold in my hands, and picture him if I use them. The blue sweater is.

markers, the many vacations, and of course, the swatting games he played with the grandkids, will always bring back great memories of my dad. All of those things bring images of my dad and what an amazing man he was, but they are not things I can hold in my hands, and picture him if I use them. The blue sweater is.

Memories are the most precious things we have once a parent has passed, and I treasure every memory I have of my dad, as I do my mom, and there are things that will always remind me of them. And one of those things will always be that blue sweater. Today would have been my dad’s 91st birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven Dad. Have a wonderful celebration. We love and miss you both very much.

When most of us think of the pioneers traveling to the West, we think of the Gold Rush, but that was not the original reason the pioneers left the East. The East had become crowded. The availability of farm land was very scarce, and soon the crowded conditions became unbearable for many people. The West offered wide open spaces, farm land, and new scenery. It was the perfect solution for the city cramped, lovers of the wide open spaces. The biggest problem with the move West was the land disputes that existed. The British wanted to claim the land because they had reached it by sea, but Lewis and Clark were the first to make a land crossing. Russia and Spain had tried to claim ownership, but that fight was settled by treaty. Still the battle for Oregon remained for a time, between Great Britain and the United States of America. Of course, in the end the United States would win in that battle, as they had for their freedom from Great Britain years before. This land would belong to the United States of America, from Texas to Canada, and Maine to California.

When most of us think of the pioneers traveling to the West, we think of the Gold Rush, but that was not the original reason the pioneers left the East. The East had become crowded. The availability of farm land was very scarce, and soon the crowded conditions became unbearable for many people. The West offered wide open spaces, farm land, and new scenery. It was the perfect solution for the city cramped, lovers of the wide open spaces. The biggest problem with the move West was the land disputes that existed. The British wanted to claim the land because they had reached it by sea, but Lewis and Clark were the first to make a land crossing. Russia and Spain had tried to claim ownership, but that fight was settled by treaty. Still the battle for Oregon remained for a time, between Great Britain and the United States of America. Of course, in the end the United States would win in that battle, as they had for their freedom from Great Britain years before. This land would belong to the United States of America, from Texas to Canada, and Maine to California.

The Oregon trail was used for eight decades as the  natural corridor between east and west during the 1800s. The trail runs approximately 2,000 miles from Independence, Missouri to Oregon City, Oregon. It also sports spur trails to Salt Lake City, which was used when the Mormon people began moving there to escape what they felt was religious persecution, and to California, which kicked off during the gold rush. Originally, however, the Oregon Trail was a series of unconnected trails used by the Indians. The Fur Traders expanded the route for the purpose of transporting pelts to trading ports and rendezvous, but the main usage of the Oregon Trail came when a series of economic and political events converged in the 1840s to start a large scale migration west. And oddly, it had nothing to do with gold.

natural corridor between east and west during the 1800s. The trail runs approximately 2,000 miles from Independence, Missouri to Oregon City, Oregon. It also sports spur trails to Salt Lake City, which was used when the Mormon people began moving there to escape what they felt was religious persecution, and to California, which kicked off during the gold rush. Originally, however, the Oregon Trail was a series of unconnected trails used by the Indians. The Fur Traders expanded the route for the purpose of transporting pelts to trading ports and rendezvous, but the main usage of the Oregon Trail came when a series of economic and political events converged in the 1840s to start a large scale migration west. And oddly, it had nothing to do with gold.

As my sisters and I were going through our parents’ things this past weekend, we came across a book about the Oregon Trail. It brought back so many memories of our family vacations, and just how excited Dad and Mom got about seeing an Oregon Trail marker. I ended up with the book, and as I was looking through it, the memories continued to flow, but what was missing was the reason the pioneers went to Oregon in the first place. I’m not sure why I didn’t know exactly, because I’m sure my Dad would  have told us, and I’m equally sure that it was in my history books. Of course, both of those sources would have required me to listen to them, and history was not really of interest to me then…ironic isn’t it? Nevertheless, the good news is that it is never to late to learn, and this week I learned something new about all those Oregon Trail monuments Dad and Mom took us to, and the significance they had on this nation…and even my own life. The ruts I’ve seen mean more to me now, and maybe I’ll have to go see them again, and if I get real ambitious, maybe Bob and I will have a new trail to think about conquering. I wonder what he will say about that idea.

have told us, and I’m equally sure that it was in my history books. Of course, both of those sources would have required me to listen to them, and history was not really of interest to me then…ironic isn’t it? Nevertheless, the good news is that it is never to late to learn, and this week I learned something new about all those Oregon Trail monuments Dad and Mom took us to, and the significance they had on this nation…and even my own life. The ruts I’ve seen mean more to me now, and maybe I’ll have to go see them again, and if I get real ambitious, maybe Bob and I will have a new trail to think about conquering. I wonder what he will say about that idea.

Our nephew, Barry’s wife, Kelli has always been an outdoor girl. She loves hiking and long drives…going just about anywhere. Saturdays often will find them heading out for a drive, and posting pictures of the things they see on Facebook or Twitter. Kelli loves to travel and, while Texas is the place she likes the best, so far, you never know if, in their travels, she just might find a place she likes better.

Our nephew, Barry’s wife, Kelli has always been an outdoor girl. She loves hiking and long drives…going just about anywhere. Saturdays often will find them heading out for a drive, and posting pictures of the things they see on Facebook or Twitter. Kelli loves to travel and, while Texas is the place she likes the best, so far, you never know if, in their travels, she just might find a place she likes better.

During various vacations, Kelli and Barry have hiked in a number of places. On trips down to Colorado to visit her mom, they have hiked in the Rocky Mountain National Park. They have also hiked in the Black Hills, the Oregon Trail, the Big Horn Mountains, and many other places. A love of hiking and the mountains is something Kelli and I definitely share. We also share a love of beautiful nature scenes, and I have really enjoyed the pictures she has posted.

Kelli loves animals. She likes the wild animals in nature, and she loves her dog, Dakota, but the thing that surprised me the most is her love of donkeys. I can relate to that in that  when we go to the Black Hills, one of the highlights of the trip is being able to see the wild donkeys there, but Kelli would love to raise donkeys. That is something I had never considered doing. Donkeys are so sweet though, and I think that would be a really cool thing to do, and I hope she will get the chance to make that dream come true someday.

when we go to the Black Hills, one of the highlights of the trip is being able to see the wild donkeys there, but Kelli would love to raise donkeys. That is something I had never considered doing. Donkeys are so sweet though, and I think that would be a really cool thing to do, and I hope she will get the chance to make that dream come true someday.

Kelli has been a part of our family since she and Barry were married in 2004. They share so many common interests, and it seems like they have always been together. Today is Kelli’s birthday. Happy birthday Kelli!! We love you!! Have a great day!!