measles

When Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and their family contracted the measles in 1847, little did they know that it would not be measles that would endanger their lives, but the treatment given after they got over the measles. The Whitmans were American missionaries who lived and worked in the area of what is now Walla Walla, Washington. When the measles broke out, the missionaries managed to survive the disease, most likely by using normal medical protocols, but the Cayuse Indians, who lived in the area, and weren’t known for cleanliness, did not fare so well. Of course, there is no proof that it was a lack of cleanliness that caused the deaths, nor was there proof that it did not. The main reason that the Whitman Mission was included in the ensuing massacre is that the Cayuse came to them for help, and lives were lost.

When Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and their family contracted the measles in 1847, little did they know that it would not be measles that would endanger their lives, but the treatment given after they got over the measles. The Whitmans were American missionaries who lived and worked in the area of what is now Walla Walla, Washington. When the measles broke out, the missionaries managed to survive the disease, most likely by using normal medical protocols, but the Cayuse Indians, who lived in the area, and weren’t known for cleanliness, did not fare so well. Of course, there is no proof that it was a lack of cleanliness that caused the deaths, nor was there proof that it did not. The main reason that the Whitman Mission was included in the ensuing massacre is that the Cayuse came to them for help, and lives were lost.

The Whitman massacre, which was also known as the Whitman killings and the Tragedy at Waiilatpu, mostly refers to the killing of American missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman, and eleven others who were involved with the mission, on November 29, 1847. The missionaries were killed by a small group of Cayuse men who accused Whitman of poisoning 200 Cayuse in his medical care during an outbreak of measles that included the Whitman household. The massacre occurred at the Whitman Mission at the junction of the Walla Walla River and Mill Creek in what is now southeastern Washington near Walla Walla. That massacre changed everything in the history of the Pacific Northwest…at least as far as the Oregon Territory was concerned anyway. The massacre caused the United States Congress to take action declaring the territorial status of the Oregon Country, thereby establishing the Oregon Territory on August 14, 1848, to protect the white settlers.

The Cayuse justified the killings by saying that any time a “medicine man” failed to bring about healing to a patient, the medicine man was killed for giving out “bad medicine” to his patients. Basically, the “medicine man” who officiated over a terminal patient, had better plan on going with the patient, because any death was going to be his fault. Basically, the Cayuse looked at Whitman’s failure to cure the Cayuse people as a criminal inability to perform his duties as “medicine man.” Of course, their “findings” were not logical, but they weren’t  thinking logically and didn’t really care anyway. The warriors were simply acting out of grief and an expectation of revenge for what they believed was a serious injustice against their people. In the White Man’s language, the massacre is usually ascribed to “the inability of Whitman, a physician, to prevent the measles outbreak.” At least three Cayuse villages held Whitman responsible for the widespread epidemic that killed those hundreds of Cayuse people, while leaving the White settlers comparatively unscathed. Some Cayuse people even accused the settlers of poisoning the Cayuse as part of a plan to take their land. Of course, justice needed to be carried out, and in the trial of five Cayuse warriors accused of the killing, the Cayuse used for their defense that it was tribal law to kill the medicine man who gives bad medicine.

thinking logically and didn’t really care anyway. The warriors were simply acting out of grief and an expectation of revenge for what they believed was a serious injustice against their people. In the White Man’s language, the massacre is usually ascribed to “the inability of Whitman, a physician, to prevent the measles outbreak.” At least three Cayuse villages held Whitman responsible for the widespread epidemic that killed those hundreds of Cayuse people, while leaving the White settlers comparatively unscathed. Some Cayuse people even accused the settlers of poisoning the Cayuse as part of a plan to take their land. Of course, justice needed to be carried out, and in the trial of five Cayuse warriors accused of the killing, the Cayuse used for their defense that it was tribal law to kill the medicine man who gives bad medicine.

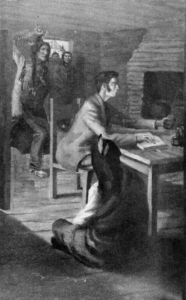

Everything blew up on November 29, 1847, when Tiloukaikt, Tomahas, Kiamsumpkin, Iaiachalakis, Endoklamin, and Klokomas, who were enraged by Joe Lewis’ talk, attacked Waiilatpu. According to Mary Ann Bridger, the young daughter of mountain man Jim Bridger, who was a lodger of the mission and eyewitness to the event, the men knocked on the Whitmans’ kitchen door and demanded medicine. Bridger went on to say that “Marcus brought the medicine and began a conversation with Tiloukaikt. While Whitman was distracted, Tomahas struck him twice in the head with a hatchet from behind and another man shot him in the neck. The Cayuse men rushed outside and attacked the white men and boys working outdoors.” Whitman’s wife, Narcissa found him fatally wounded, and while he lived for several hours after the attack, and sometimes responded to her anxious reassurances, he later died of his injuries. Catherine Sager, who had been with Narcissa in another room when the attack occurred, later wrote in her reminiscences that “Tiloukaikt chopped the doctor’s face so badly that his features could not be recognized.”

Had she stayed hidden, Narcissa might have lived through the attack, but she later went to the door to look out and was immediately shot by a Cayuse man. Then she was coaxed out of the house. She died from a volley of

gunshots immediately upon leaving the house. The rest of the people killed in the massacre were Andrew Rodgers, Jacob Hoffman, LW Saunders, Walter Marsh, John and Francis Sager, Nathan Kimball, Isaac Gilliland, James Young, Crocket Bewley, and Amos Sales. A carpenter who had been working on the house, Peter Hall managed to escape the massacre and reach Fort Walla Walla to raise the alarm and get help. After leaving Fort Walla Walla, he left to warn Fort Vancouver, but he never made it. Sone think that Hall drowned in the Columbia River, while others speculate that he was caught and killed. On man, Chief “Beardy” tried to stop the massacre, but it was too out of control. The warriors were insanely crazy with grief, and nothing was going to stop their revenge. Chief “Beardy” was found crying while riding toward the Whitman Mission.

gunshots immediately upon leaving the house. The rest of the people killed in the massacre were Andrew Rodgers, Jacob Hoffman, LW Saunders, Walter Marsh, John and Francis Sager, Nathan Kimball, Isaac Gilliland, James Young, Crocket Bewley, and Amos Sales. A carpenter who had been working on the house, Peter Hall managed to escape the massacre and reach Fort Walla Walla to raise the alarm and get help. After leaving Fort Walla Walla, he left to warn Fort Vancouver, but he never made it. Sone think that Hall drowned in the Columbia River, while others speculate that he was caught and killed. On man, Chief “Beardy” tried to stop the massacre, but it was too out of control. The warriors were insanely crazy with grief, and nothing was going to stop their revenge. Chief “Beardy” was found crying while riding toward the Whitman Mission.

Israel Putnam Spencer, who is my sixth cousin twice removed, was a writer in his own right. He wrote a journal of sorts that dated back to his earliest recollections, beginning at about four or five years of age. Not everyone can remember very much about themselves at that age, although I think a number of us can. Usually it is some traumatic even, such as illness, a death, or as in my cast, an accident, in which I lost a fight with an escalator. For Israel, it was both illness and death. Israel states that he was just “getting over a spell of sickness” in the town of DeRuyter, Madison County, New York. He talks of moving to Corning, Steuben County, New York where the family lived another four years. This place had no stove, so cooking was done over the fire in the fireplace. It was in Corning that he and his sister got the measles, and his aunt, his mother’s sister died…probably also of measles, as they were very dangerous in those days. His writings tell of hard times…of moving to live with his mother’s brother, Frank Lewis. Hard times in that after finding a dog and being so excited to have a pet, they had to give the dog to a cousin. I’m sure these things all seemed extra hard to a young boy of about nine or ten. Yet, in the midst of those hard times, the family arrived at Israel’s Uncle Frank’s house, to find the dog, that they hadn’t seen in two years…and the dog remembered them, and was so excited to see them. That friendship must have felt like the sun coming out after a long raging storm.

Israel Putnam Spencer, who is my sixth cousin twice removed, was a writer in his own right. He wrote a journal of sorts that dated back to his earliest recollections, beginning at about four or five years of age. Not everyone can remember very much about themselves at that age, although I think a number of us can. Usually it is some traumatic even, such as illness, a death, or as in my cast, an accident, in which I lost a fight with an escalator. For Israel, it was both illness and death. Israel states that he was just “getting over a spell of sickness” in the town of DeRuyter, Madison County, New York. He talks of moving to Corning, Steuben County, New York where the family lived another four years. This place had no stove, so cooking was done over the fire in the fireplace. It was in Corning that he and his sister got the measles, and his aunt, his mother’s sister died…probably also of measles, as they were very dangerous in those days. His writings tell of hard times…of moving to live with his mother’s brother, Frank Lewis. Hard times in that after finding a dog and being so excited to have a pet, they had to give the dog to a cousin. I’m sure these things all seemed extra hard to a young boy of about nine or ten. Yet, in the midst of those hard times, the family arrived at Israel’s Uncle Frank’s house, to find the dog, that they hadn’t seen in two years…and the dog remembered them, and was so excited to see them. That friendship must have felt like the sun coming out after a long raging storm.

Soon things were looking up for the family, and Israel’s dad bought a farm where the family lived until Israel was fourteen and then he traded that farm for a 100 acre farm just a sort distance away. That farm brought about a big change for the Israel and his brothers because they now have to work the farm, in order to keep up. They went to school in the winter and worked the farm in summer. Then Israel writes of reaching an age where he got a “big head” like most boys did at about 15 to 18 years of age. He said that he got to a point where he was convinced that he knew more than the teachers and his parents combined, and so he quit school at 17 years old. He got odd jobs, and made about $15.00 a month…about average for a 17 year old in those days, I suppose, but maybe less than if he had more schooling…these days anyway.

Then came the biggest change of Israel’s life…the Civil War started in 1861. His oldest brother, Morton Spencer  enlisted in Company E, 23rd New York Infantry for two years. Shortly thereafter, Israel’s brother Fred Spencer enlisted, and Israel joined him. It was August 6th of 1862, and Israel was 18 years and 2 months old. Israel tells of his time spent in the war, with an insider’s view that most of us never got to hear about. The northern army, and I suspect the southern army as well, were having trouble keeping their officers. Back then, they didn’t have the came controls over the people in the army. A person could be missing for weeks before anyone really got word of it. Of course, when an officer goes missing, and you are one of his men, you know it, and that is what happened at times…especially when the war put brother against brother, as was the case in the Civil War. He survived the war, as did his brothers, but those were days of hunger and lack. He chose in later years, not to talk about them much, because who would want to remember such a time. He did write about those day, and there are many more tales to tell of the Civil War, but that is a story for another day.

enlisted in Company E, 23rd New York Infantry for two years. Shortly thereafter, Israel’s brother Fred Spencer enlisted, and Israel joined him. It was August 6th of 1862, and Israel was 18 years and 2 months old. Israel tells of his time spent in the war, with an insider’s view that most of us never got to hear about. The northern army, and I suspect the southern army as well, were having trouble keeping their officers. Back then, they didn’t have the came controls over the people in the army. A person could be missing for weeks before anyone really got word of it. Of course, when an officer goes missing, and you are one of his men, you know it, and that is what happened at times…especially when the war put brother against brother, as was the case in the Civil War. He survived the war, as did his brothers, but those were days of hunger and lack. He chose in later years, not to talk about them much, because who would want to remember such a time. He did write about those day, and there are many more tales to tell of the Civil War, but that is a story for another day.