lusitania

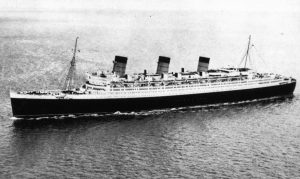

As ocean liners began to be built, sailing the worlds oceans suddenly went from an ordeal that was tolerated in order to improve their lives, to a way to see the world in luxury and relative speed. Emigration to the United States brought with it the need for many great ocean liners, and as they began to appear, the world became mobile. Prior to these ocean liners, it wouldn’t have been possible to really populate the new world. Europe was overcrowded, and the United States was underpopulated. Ocean liners like the Queen Mary, the Mauritania, the Lusitania, the Queen Elizabeth all made travel to the United States and even back to Europe a luxury.

As ocean liners began to be built, sailing the worlds oceans suddenly went from an ordeal that was tolerated in order to improve their lives, to a way to see the world in luxury and relative speed. Emigration to the United States brought with it the need for many great ocean liners, and as they began to appear, the world became mobile. Prior to these ocean liners, it wouldn’t have been possible to really populate the new world. Europe was overcrowded, and the United States was underpopulated. Ocean liners like the Queen Mary, the Mauritania, the Lusitania, the Queen Elizabeth all made travel to the United States and even back to Europe a luxury.

During the world wars, the military commandeered these cruise ships for troop transports, and also for munitions transports. It was not always safe for these ships to be carrying civilian passengers, as was seen with the sinking of the Lusitania, so after a time the cruise ships had to stop their civilian trips and become troop transports exclusively. They had to stop, because whether the ship had munitions on it or not, it was sunk with civilian passengers onboard.

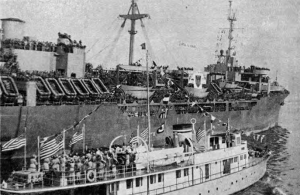

At a time when there were no passenger planes, ocean liners provided the only pathway to cross the oceans. Once war in Europe had begun, many of the great ocean liners of the period withdrew from transatlantic crossings. However, they still remained at sea. Wartime saw ocean liners converted into troopships, carrying thousands of soldiers on a single trip, from bases in the United States to bases in the theaters in Europe, Africa, and Japan. Some of the most famous names in steamship history, including Mauretania, Olympic, Leviathan,  Nieuw Amsterdam (II), Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth II were among those converted to troopships during times of war. These ships were a critical part of military operations. Without their support, transporting troops, equipment, and munitions would have taken far too long to do any good. These ships were the fastest ships out there at that time in history, and time was of the essence.

Nieuw Amsterdam (II), Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth II were among those converted to troopships during times of war. These ships were a critical part of military operations. Without their support, transporting troops, equipment, and munitions would have taken far too long to do any good. These ships were the fastest ships out there at that time in history, and time was of the essence.

Of course, these ships faced the threat of submarine or airborne attack, so speed was the greatest defense the ship could have, but they couldn’t just start using the ships. These ships had to go through a process of preparation before they could be a transport ship. All of the items that were not needed for sustaining or berthing the maximum number of troops, were among the first things to go. Furniture, paintings, pianos, and everything else not needed for war would be removed and stored on land, to be returned to the ship after the war was over. The empty space was then filled with hammocks and cots for the soldiers to sleep on. They mounted guns on the decks to provide defensive capability. Of course, these liners could not act as a warship. They were just not designed for that, but a few well placed shots, might deter some of the smaller boats like U-boats from making a surface attack.

Camouflage was considered a critical part of the liners ability to survive in hostile waters. They applied “dazzle paint” to the hulls of these ocean liners. Oddly, the paint closely resembling zebra stripes!! They reasoned that alternating dark and light stripes would obscure the size, speed, heading, and type of ship when viewed from a distance. I can’t picture that exactly, and apparently it wasn’t very effective either. I guess all that it really did  was to give a false sense of security to the soldiers on board.

was to give a false sense of security to the soldiers on board.

Following the war, and ship that survived their wartime duties was restored to its former look and feel so that it could continue with its pre-war duties. Unfortunately, many of these beautiful ocean liners were lost to enemy fire during the war. Sadly, there are no real examples of these wartime liners turned troop transports, but the Queen Mary is in dry dock in Long Beach, California. Visitors can take a tour, and get a real feel for those cramped quarters. Visitors can imagine the soldiers felt as they crossed the North Atlantic, knowing that their ship was a prized target for the enemy.

On January 31, 1917, at the height of World War I, Germany announced that they would renew the use of unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic Ocean. The German torpedo-armed submarines, known as U-Boats, prepared to attack any and all ships operating in the Atlantic, including civilian passenger carriers, which were said to have been sighted in war-zone waters. They were prepared to attack without a second thought, whether they were innocent civilians or not. Unleashing the U-Boats was almost like unleashing terrorists, because the U-Boats were an invisible enemy. Yes, the could be seen, but beneath the surface of the water, they could easily hide in the murky darkness, unleashing their torpedoes to go streaking through the water. The first sign of danger was when the doomed ship watchmen saw the dreaded white streak coming at them through the water. There was no time to take evasive action. The ship could not move that fast, and it could not turn on a dime. They were sitting ducks.

On January 31, 1917, at the height of World War I, Germany announced that they would renew the use of unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic Ocean. The German torpedo-armed submarines, known as U-Boats, prepared to attack any and all ships operating in the Atlantic, including civilian passenger carriers, which were said to have been sighted in war-zone waters. They were prepared to attack without a second thought, whether they were innocent civilians or not. Unleashing the U-Boats was almost like unleashing terrorists, because the U-Boats were an invisible enemy. Yes, the could be seen, but beneath the surface of the water, they could easily hide in the murky darkness, unleashing their torpedoes to go streaking through the water. The first sign of danger was when the doomed ship watchmen saw the dreaded white streak coming at them through the water. There was no time to take evasive action. The ship could not move that fast, and it could not turn on a dime. They were sitting ducks.

The vast majority of people of the United States favored neutrality when it came to World War I. So when the war erupted in 1914, President Woodrow Wilson pledged the stay neutral. The problem was that Britain was one of America’s closest trading partners. That created serious tension between the United States and Germany, when Germany attempted a blockade of the British isles. Several US ships traveling to Britain were damaged or sunk by German mines and, in February 1915, Germany announced unrestricted warfare against all ships, neutral or otherwise, that entered the war zone around Britain. One month later, Germany announced that a German cruiser had sunk the William P. Frye, a private American merchant vessel that was transporting grain to England when it disappeared. President Wilson was outraged, but the German government apologized, calling the attack an unfortunate mistake. That didn’t stop their reign of terror, however. In November they sank an Italian liner without warning, killing 272 people, including 27 Americans. Public opinion concerning the war, and the stand of the United States in it began to change. It was time for the United States to get into World War I.

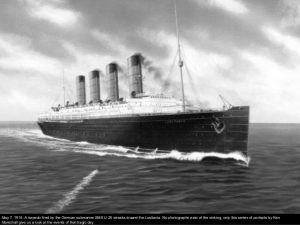

The Germans were far in advance of other nations when it came to submarines. The U-boat was 214 feet long, carried 35 men and 12 torpedoes, and could travel underwater for two hours at a time. In the first few years of World War I, the U-boats took a terrible toll on Allied shipping. In early May 1915, several New York newspapers had to publish a warning by the German embassy in Washington that Americans traveling on British or Allied ships in war zones did so at their own risk. The announcement was placed on the same page as an advertisement for the imminent sailing of the British-owned Lusitania ocean liner from New York to Liverpool. I’m sure they had hoped that people would heed the warning, but many people boarding the Lusitania either didn’t take notice of the warning or they didn’t see it. On May 7, the Lusitania was torpedoed without warning just off the coast of Ireland. Of the 1,959 passengers, 1,198 were killed, including 128 Americans. The Germans had proven once again that they were ruthless and conniving. Following the sinking of the Lusitania The German government accused the Lusitania was carrying munitions. The US demanded an end to German attacks on unarmed passenger and merchant ships, and full repayment for the loss.

Following the sinking of the Lusitania the German government accused the Lusitania was carrying munitions. The US demanded an end to German attacks on unarmed passenger and merchant ships, and full repayment for the loss. Germany countered with a pledge to see to the safety of passengers before sinking unarmed vessels in August 1915. All that changed by January 1917, when Germany, determined to win its war of attrition against the Allies, announced the resumption of unrestricted warfare. Three days later, the United States broke off diplomatic relations with Germany, who, just hours later sunk the American liner Housatonic. None of the 25 Americans on board were killed and they were picked up by a British steamer.

On February 22, Congress passed a $250 million arms-appropriations bill intended to ready the United States for war. British authorities gave the US ambassador to Britain a copy of what has become known as the “Zimmermann Note,” a coded message from German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann to Count Johann von Bernstorff, the German ambassador to Mexico. In the telegram, intercepted and deciphered by British intelligence, Zimmermann stated that, in the event of war with the United States, Mexico should be asked to  enter the conflict as a German ally. In return, Germany would promise to restore to Mexico the lost territories of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. On March 1, the outraged US State Department published the note and America was galvanized against Germany once and for all. In late March, Germany sank four more US merchant ships. President Wilson appeared before Congress and called for a declaration of war against Germany on April 2nd. On April 4th, the Senate voted 82 to six to declare war against Germany. Two days later, the House of Representatives endorsed the declaration by a vote of 373 to 50 and America formally entered World War I. They were after that invisible enemy, and they were determined to find it and destroy it.

enter the conflict as a German ally. In return, Germany would promise to restore to Mexico the lost territories of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. On March 1, the outraged US State Department published the note and America was galvanized against Germany once and for all. In late March, Germany sank four more US merchant ships. President Wilson appeared before Congress and called for a declaration of war against Germany on April 2nd. On April 4th, the Senate voted 82 to six to declare war against Germany. Two days later, the House of Representatives endorsed the declaration by a vote of 373 to 50 and America formally entered World War I. They were after that invisible enemy, and they were determined to find it and destroy it.

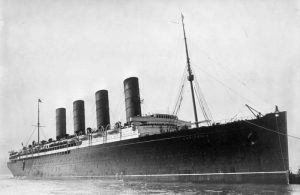

Most people have heard of the Titanic sinking, and how disaster could have been prevented, had they just slowed down, listened to the warnings, and had they had enough lifeboats. There is, however, another ship sinking that not so many people have heard of, or if they had, they didn’t pay much attention to. It is the Lusitania. Like the Titanic, the sinking of the Lusitania could have been prevented too, had a number of simple precautions been taken, such as not to sail at all that fateful May day in 1915.

Most people have heard of the Titanic sinking, and how disaster could have been prevented, had they just slowed down, listened to the warnings, and had they had enough lifeboats. There is, however, another ship sinking that not so many people have heard of, or if they had, they didn’t pay much attention to. It is the Lusitania. Like the Titanic, the sinking of the Lusitania could have been prevented too, had a number of simple precautions been taken, such as not to sail at all that fateful May day in 1915.

RMS Lusitania left New York for Britain on May 1, 1915, unfortunately during a time when German submarine warfare was intensifying in the Atlantic. On February 4, 1915, Germany had declared the seas around the United Kingdom a war zone, and the German embassy in the United States had placed newspaper advertisements warning people of the dangers of sailing on Lusitania. Not to defend the Germans, but they had warned people that they would attack all ships, military or passenger. Unfortunately, not many people boarding Lusitania that morning had time to read the paper before embarking on their journey. It amazes me that it was left to the people, who were told that the ship could outrun the German U-boats. They were also told that they  would have escort ships as they entered the war zone. And, they were told that the U-boats were not attacking neutral passenger liners. Unfortunately, these things were not factual. Part of the problem was that the Allies had begun disguising war ships as passenger ships on the assumption that the Germans would not attack passenger ships. Other passenger ships were actually used to transport soldiers and ammunition, or even just ammunition, in the thought that they would be safe from harm that way. The Allies were also supposed to have escort ships to take the passenger ships, but that did not happen in the case of the Lusitania.

would have escort ships as they entered the war zone. And, they were told that the U-boats were not attacking neutral passenger liners. Unfortunately, these things were not factual. Part of the problem was that the Allies had begun disguising war ships as passenger ships on the assumption that the Germans would not attack passenger ships. Other passenger ships were actually used to transport soldiers and ammunition, or even just ammunition, in the thought that they would be safe from harm that way. The Allies were also supposed to have escort ships to take the passenger ships, but that did not happen in the case of the Lusitania.

The sinking of the Cunard ocean liner RMS Lusitania occurred on Friday, May 7, 1915 during the First World War, as Germany waged submarine warfare against the United Kingdom which had implemented a naval blockade of Germany. The ship was identified and torpedoed by the German U-boat U-20 and sank in just 18 minutes, and also took on a heavy starboard list. The Lusitania went down 11 miles off the Old Head of Kinsale,  Ireland, killing 1,198 and leaving 761 survivors. The sinking turned public opinion in many countries against Germany, and it was a key element in the American entry into World War I. The torpedoing and subsequent sinking became an iconic symbol in military recruiting campaigns. The injustice of it brought about the outrage that would likely cause soldiers to enlist. Still, the United States did not immediately enter into the war. The American government first issued a severe protest to Germany…a waste of time really. Then, following immense pressure from the United States and recognizing the limited effectiveness of the policy, Germany abandoned unrestricted submarine warfare in September 1915.

Ireland, killing 1,198 and leaving 761 survivors. The sinking turned public opinion in many countries against Germany, and it was a key element in the American entry into World War I. The torpedoing and subsequent sinking became an iconic symbol in military recruiting campaigns. The injustice of it brought about the outrage that would likely cause soldiers to enlist. Still, the United States did not immediately enter into the war. The American government first issued a severe protest to Germany…a waste of time really. Then, following immense pressure from the United States and recognizing the limited effectiveness of the policy, Germany abandoned unrestricted submarine warfare in September 1915.

During World War I, the Germans had taken a hard line concerning the waters around England. It was called unrestricted submarine warfare, and it meant that German submarines would attack any ship found in the war zone, which, in this case, was the area around the British Isles…no matter what kind of ship it was, and even if it was from a neutral country. Of course, this was not going to fly, and since Germany was afraid of the United States, they finally agreed to only go after military ships. Nevertheless, mistakes can be made, and that is what happened on May 7, 1915, when a German U-boat torpedoed and sank the RMS Lusitania, a British ocean liner en route from New York to Liverpool, England. Of the more than 1,900 passengers and crew members on board, more than 1,100 perished, including more than 120 Americans. A warning had been placed in several New York newspapers in early May 1915, by the German Embassy in Washington, DC, stating that Americans traveling on British or Allied ships in war zones did so at their own risk. The announcement was placed on the same page as an advertisement of the imminent sailing of the Lusitania liner from New York back to Liverpool. Still this did not stop the sailing of the Lusitania, because the captain of the Lusitania ignored the British Admiralty’s recommendations, and at 2:12 pm on May 7 the 32,000-ton ship was hit by an exploding torpedo on its starboard side. The torpedo blast was followed by a larger explosion, probably of the ship’s boilers, and the ship sank off the south coast of Ireland in less than 20 minutes.

During World War I, the Germans had taken a hard line concerning the waters around England. It was called unrestricted submarine warfare, and it meant that German submarines would attack any ship found in the war zone, which, in this case, was the area around the British Isles…no matter what kind of ship it was, and even if it was from a neutral country. Of course, this was not going to fly, and since Germany was afraid of the United States, they finally agreed to only go after military ships. Nevertheless, mistakes can be made, and that is what happened on May 7, 1915, when a German U-boat torpedoed and sank the RMS Lusitania, a British ocean liner en route from New York to Liverpool, England. Of the more than 1,900 passengers and crew members on board, more than 1,100 perished, including more than 120 Americans. A warning had been placed in several New York newspapers in early May 1915, by the German Embassy in Washington, DC, stating that Americans traveling on British or Allied ships in war zones did so at their own risk. The announcement was placed on the same page as an advertisement of the imminent sailing of the Lusitania liner from New York back to Liverpool. Still this did not stop the sailing of the Lusitania, because the captain of the Lusitania ignored the British Admiralty’s recommendations, and at 2:12 pm on May 7 the 32,000-ton ship was hit by an exploding torpedo on its starboard side. The torpedo blast was followed by a larger explosion, probably of the ship’s boilers, and the ship sank off the south coast of Ireland in less than 20 minutes.

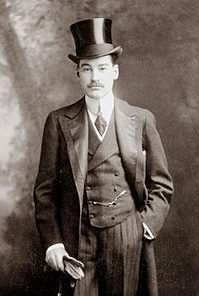

While the sinking of the Lusitania was a horrible tragedy, there were heroics too. One such hero was Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, Sr. Vanderbilt was an extremely wealthy American businessman and sportsman, and a member of the famous Vanderbilt family, but on this trip, he was so much more than that. On May 1, 1915, Alfred Vanderbilt boarded the RMS Lusitania bound for Liverpool as a first class passenger. Vanderbilt was on a business trip. He was traveling with only his valet, Ronald Denyer. His family stayed at home in New York. On May 7, off the coast of County Cork, Ireland, German U-boat, U-20 torpedoed the ship, triggering a secondary explosion that sank the giant ocean liner within 18 minutes. Vanderbilt and Denyer immediately went into action, helping others into lifeboats, and then Vanderbilt gave his lifejacket to save a female passenger. Vanderbilt had promised the young mother of a small baby that he would locate an extra life vest for her. Failing to do so, he offered her his own life vest, which he proceeded to tie on to her himself, because she was holding her infant child in her arms at the time.

Vanderbilt had to know he was sealing his own fate, since he could not swim and he knew there were no other life vests or lifeboats available. They were in waters where no outside help was likely to be coming. Still, he  gave his life for hers and that of her child. Because of his fame, several people on the Lusitania who survived the tragedy were observing him while events unfolded at the time, and so they took note of his actions. I suppose that had he not been famous, people would not have known who he was to tell the story. Vanderbilt and Denyer were among the 1198 passengers who did not survive the incident. His body was never recovered. Probably the most ironic fact is that three years earlier Vanderbilt had made a last-minute decision not to return to the US on RMS Titanic. In fact, his decision not to travel was made so late that some newspaper accounts listed him as a casualty after that sinking too. He would not be so fortunate when he chose to travel on Lusitania.

gave his life for hers and that of her child. Because of his fame, several people on the Lusitania who survived the tragedy were observing him while events unfolded at the time, and so they took note of his actions. I suppose that had he not been famous, people would not have known who he was to tell the story. Vanderbilt and Denyer were among the 1198 passengers who did not survive the incident. His body was never recovered. Probably the most ironic fact is that three years earlier Vanderbilt had made a last-minute decision not to return to the US on RMS Titanic. In fact, his decision not to travel was made so late that some newspaper accounts listed him as a casualty after that sinking too. He would not be so fortunate when he chose to travel on Lusitania.

While Germany was willing to go to war, they had, nevertheless, a healthy fear of the United States. During World War I, Germany introduced unrestricted submarine warfare. It was early 1915, and Germany decided that the area around the British Isles was a war zone, and all merchant ships, including those from neutral countries, would be attacked by the German navy. That action set in motion a series of attacks on merchant ships, that finally led to the sinking of the British passenger ship, RMS Lusitania on May 7, 1915. It was at this point that President Woodrow Wilson decided that it was time to pressure the German government to curb their naval actions. Because the German government didn’t want to antagonize the United States, they agreed to put restrictions on the submarine policy going forward, which angered many of their naval leaders, including the naval commander in chief, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who showed his frustration by resigning in March 1916.

While Germany was willing to go to war, they had, nevertheless, a healthy fear of the United States. During World War I, Germany introduced unrestricted submarine warfare. It was early 1915, and Germany decided that the area around the British Isles was a war zone, and all merchant ships, including those from neutral countries, would be attacked by the German navy. That action set in motion a series of attacks on merchant ships, that finally led to the sinking of the British passenger ship, RMS Lusitania on May 7, 1915. It was at this point that President Woodrow Wilson decided that it was time to pressure the German government to curb their naval actions. Because the German government didn’t want to antagonize the United States, they agreed to put restrictions on the submarine policy going forward, which angered many of their naval leaders, including the naval commander in chief, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who showed his frustration by resigning in March 1916.

On March 24, 1916, soon after Tirpitz’s resignation, a German U-boat submarine attacked the French passenger steamer Sussex, in the English Channel, thinking it was a British ship equipped to lay explosive mines. It was apparently an honest mistake, and the ship did not sink. Still, 50 people were killed and many  more injured, including several Americans. On April 19, in an address to the United States Congress, President Wilson took a firm stance, stating that unless the Imperial German Government agreed to immediately abandon its present methods of warfare against passenger and freight carrying vessels the United States would have no choice but to sever diplomatic relations with the Government of the German Empire altogether.

more injured, including several Americans. On April 19, in an address to the United States Congress, President Wilson took a firm stance, stating that unless the Imperial German Government agreed to immediately abandon its present methods of warfare against passenger and freight carrying vessels the United States would have no choice but to sever diplomatic relations with the Government of the German Empire altogether.

After Wilson’s speech, the US ambassador to Germany, James W. Gerard, spoke directly to Kaiser Wilhelm on May 1 at the German army headquarters at Charleville in eastern France. After Gerard protested the continued German submarine attacks on merchant ships, the Kaiser in turn denounced the American government’s compliance with the Allied naval blockade of Germany, in place since late 1914. Nevertheless, Germany could not risk American entry into the war against them, so when Gerard urged the Kaiser to provide assurances of a change in the submarine policy, the Kaiser agreed.

On May 6, the German government signed the so-called Sussex Pledge, promising to stop the indiscriminate sinking of non-military ships. According to the pledge, merchant ships would be searched, and sunk only if they  were found to be carrying contraband materials. Furthermore, no ship would be sunk before safe passage had been provided for the ship’s crew and its passengers. Gerard was skeptical of the intentions of the Germans, and wrote in a letter to the United States State Department that “German leaders, forced by public opinion, and by the von Tirpitz and Conservative parties would take up ruthless submarine warfare again, possibly in the autumn, but at any rate about February or March, 1917.” Gerard was right, and on February 1, 1917, Germany announced the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare. Two days later, Wilson announced a break in diplomatic relations with the German government, and on April 6, 1917, the United States formally entered World War I on the side of the Allies.

were found to be carrying contraband materials. Furthermore, no ship would be sunk before safe passage had been provided for the ship’s crew and its passengers. Gerard was skeptical of the intentions of the Germans, and wrote in a letter to the United States State Department that “German leaders, forced by public opinion, and by the von Tirpitz and Conservative parties would take up ruthless submarine warfare again, possibly in the autumn, but at any rate about February or March, 1917.” Gerard was right, and on February 1, 1917, Germany announced the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare. Two days later, Wilson announced a break in diplomatic relations with the German government, and on April 6, 1917, the United States formally entered World War I on the side of the Allies.