jews

During the Holocaust, the majority of known Jews in any given country, had a very slim chance of surviving the war, but the Denmark Jews somehow managed to hold an impressive 95% survival rate record. Much of that was due to one man, Georg Ferdinand Duckwitz, who became an unlikely hero of the Jewish people…mainly because he was a German diplomat serving as an attaché for Nazi Germany in occupied Denmark at the time. In fact, that is what makes what he did so strange.

During the Holocaust, the majority of known Jews in any given country, had a very slim chance of surviving the war, but the Denmark Jews somehow managed to hold an impressive 95% survival rate record. Much of that was due to one man, Georg Ferdinand Duckwitz, who became an unlikely hero of the Jewish people…mainly because he was a German diplomat serving as an attaché for Nazi Germany in occupied Denmark at the time. In fact, that is what makes what he did so strange.

Duckwitz was born on September 29, 1904, in Bremen, Germany. He was part of an old patrician family in the Hanseatic City. After college, he began a career in the international coffee trade. From 1928 until 1932 Duckwitz lived in Copenhagen, Denmark. Upon moving back to Bremen, November 1932 he met Gregor Strasser, who was the leader of the leftist branch of the German nationalistic Nazi Party. While talking to Strasser, Duckwitz found that “elements of Scandinavian socialism [were] connected with nationalistic feelings” and this led to his decision to join the Nazi Party, and subsequently on July 1, 1933, to join the Nazi Party’s Office of Foreign Affairs in Berlin.

What had at first seemed to him to be a party who’s values agreed with his, he soon became increasingly disillusioned by Nazi politics. In a letter written June 4, 1935 to Alfred Rosenberg, the head of the office, he wrote, “My two-year employment in the Reichsleitung [i.e. executive branch] of the [Nazi Party] has made me realize that I am so fundamentally deceived in the nature and purpose of the National Socialist movement that I am no longer able to work within this movement as an honest person.” That move in itself strikes me now, as scary, considering how the known Nazi party functioned. He may not have realized hoe dangerous his words were, but I think they could have gotten him killed. Around the same time the Gestapo (secret police) made its first notes on Duckwitz after he sheltered three Jewish women in his Kurfürstendamm apartment during a local anti-Semitic Sturmabteilung event. He later wrote that during this time period he became “a fierce opponent of this [Nazi] system”.

After 1942, Duckwitz worked with the Nazi Reich representative Werner Best, who organized the Gestapo. On September 11, 1943 Best told Duckwitz about the intended round-up of all Danish Jews on October 1, 1943. A horrified Duckwitz travelled to Berlin in an attempt to stop the deportation through official channels. When that failed, he flew to Stockholm two weeks later, saying he was going to discuss the passage of German merchant ships. While there, he contacted Prime Minister Per Albin Hansson and asked whether Sweden would be willing to receive Danish Jewish refugees. A couple of days later, Hansson came back with the promise of a favorable reception. On September, 29, 1943, Duckwitz contacted Danish social democrat Hans Hedtoft and notified him of the intended deportation. Hedtoft warned the head of the Jewish community CB Henriques and the acting chief rabbi Marcus Melchior, who spread the warning. Sympathetic Danes in all walks of life organized an immediate mass escape of over 7,200 Jews and 700 of their non-Jewish relatives by sea to Sweden. Duckwitz’ immediate action and the willingness of the Danish and Swedish citizens saved the lives of 95% of Denmark’s Jewish population. They were the only European nation to save almost all their Jewish population from certain death at the hand’s of Hitler’s evil regime.

Somehow, Duckwitz was never caught committing his act of “treason” against the Third Reich, and he stayed in good standing with the Nazi regime. After the war, Duckwitz remained in the German foreign service. From 1955– 1958 Duckwitz served as West German ambassador to Denmark and later as the ambassador to India. When Willy Brandt became Foreign Minister in 1966, he made Duckwitz Secretary of State in West Germany´s Foreign Office. After Brandt became Chancellor, he asked Duckwitz to negotiate an agreement with the Polish government. Brandt’s work culminated in the 1970 Treaty of Warsaw. Duckwitz worked as Secretary of State until his final retirement in 1970. On March 21, 1971 the Israeli government named him Righteous Among the Nations and included him in the Yad Vashem memorial. He died two years later, on February 16, 1973 at the age of 68.

1958 Duckwitz served as West German ambassador to Denmark and later as the ambassador to India. When Willy Brandt became Foreign Minister in 1966, he made Duckwitz Secretary of State in West Germany´s Foreign Office. After Brandt became Chancellor, he asked Duckwitz to negotiate an agreement with the Polish government. Brandt’s work culminated in the 1970 Treaty of Warsaw. Duckwitz worked as Secretary of State until his final retirement in 1970. On March 21, 1971 the Israeli government named him Righteous Among the Nations and included him in the Yad Vashem memorial. He died two years later, on February 16, 1973 at the age of 68.

Most people who know anything about World War II, have heard of Auschwitz. Concentration camps like the infamous Auschwitz forced people to endure inhumane treatment and poor living conditions. It was one of the worst of the death camps set up by Hitler as part of the “Final Solution” killings of Jews, Gypsies, and Jehovah’s Witnesses during and right before World War II. Nevertheless, Auschwitz wasn’t the only death camp, and some were even more afraid of going to Mauthausen than they were Auschwitz.

Most people who know anything about World War II, have heard of Auschwitz. Concentration camps like the infamous Auschwitz forced people to endure inhumane treatment and poor living conditions. It was one of the worst of the death camps set up by Hitler as part of the “Final Solution” killings of Jews, Gypsies, and Jehovah’s Witnesses during and right before World War II. Nevertheless, Auschwitz wasn’t the only death camp, and some were even more afraid of going to Mauthausen than they were Auschwitz.

Between 1939, when World War II began, to 1945 when it ended, more than 1 million of the 1.5 million Jewish children who had lived in the areas German armies occupied, had perished. The Mauthausen camp wasn’t as well known as Auschwitz, but it was equally horrific. Built in 1938, Mauthausen was one of the first concentration camps erected and the last to be liberated. It was a place where terrible medical experiments took place, and the guards humiliated the prisoners. Mauthausen “Stairs of Death” were especially tragic because prisoners were forced to climb to their deaths. This 186-step structure was brutal for prisoners. They had to carry stones weighing more than 100 pounds from the bottom of the quarry to the top of the stairs. Climbers often collapsed beneath the stones’ weight. Exhausted prisoners slid down the steps, knocking over other prisoners while the stones crushed their limbs. Nazi Party members called the camp “the Bone Grinder.”

Prisoners who actually made it to the top of those torturous steps, were then forced to make the most unthinkable decisions. The German guards lined up the survivors of the climb, then forced them to choose between either pushing a fellow prisoner off the cliff or being executed. Many prisoners opted to jump off the cliff. German officers called these acts “parachute jumps.” It didn’t matter if they had been strong enough to make the climb, carrying the 100 pound rocks, because they were to lose their lives anyway.

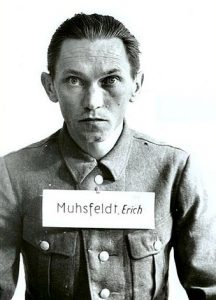

Some prisoners escaped the stairs, if it could be called escape, but they were subjected to Dr. Aribert Heim’s horrific experiments. In 1941, Heim started working at Mauthausen. His experiments involved disfiguring people indiscriminately. During his first year of employment there, guards brought in an 18-year-old Jewish athlete with a foot infection. “Heim put the teen under anesthesia, cut him open, removed his kidney, and castrated him. Finally, the doctor removed the athlete’s head, then boiled the skull to remove all the flesh. He kept the severed body part as a trophy.”

Austrian winters are brutal, with temperatures dropping to around 14 degrees Fahrenheit. The guards at Mauthausen used the frigid temperatures to torment and execute inmates. They took groups outside, forced them to strip naked, then sprayed them with water. The poor terrified prisoners were the  left to freeze. Many died of hypothermia. The guards also “enjoyed” physically and mentally abusing their prisoners. Former inmate and French resistance fighter Christian Bernadac said Mauthausen was “infernal, without a second’s rest.” Officers offered prisoners breaks from the grueling work, but then executed those who accepted. Mauthausen survivor Aba Lewitt recalled a man who met that fate: “The guard said [to the man], ‘Well, then, sit over there’ – then he shot him. [He] said the inmate tried to escape the camp. That happened umpteen times every day.”

left to freeze. Many died of hypothermia. The guards also “enjoyed” physically and mentally abusing their prisoners. Former inmate and French resistance fighter Christian Bernadac said Mauthausen was “infernal, without a second’s rest.” Officers offered prisoners breaks from the grueling work, but then executed those who accepted. Mauthausen survivor Aba Lewitt recalled a man who met that fate: “The guard said [to the man], ‘Well, then, sit over there’ – then he shot him. [He] said the inmate tried to escape the camp. That happened umpteen times every day.”

The Germans created Mauthausen to benefit Adolf Hitler’s army. They needed granite and brick for Linz, a neighboring city the dictator hoped to rebuild with huge, elaborate structures. The concentration camp sat on the edge of a granite quarry, and prisoners collected the plutonic igneous rock to form Mauthausen’s main structures. Inmates called their time there “vernichtung durch arbeit,” or “extermination by work.” They did not expect to return home.

Mauthausen was a central concentration camp, but it had numerous subcamps that surrounded it. The subcamps were connected by underground tunnels. One of these smaller subcamps, the Gusen complex, was the place they took people who were too weak to work. Gusen inmates were simply thrown on the ground and abandoned. People there were piled on top of each other, often unable to move around and covered in human excrement. German guards rarely distributed food in Gusen, so the prisoners simply starved to death.

Crazed prisoners at Mauthausen allegedly resorted to cannibalism to survive. Food was so scarce in Mauthausen, and sometimes high-ranking German guards like Oswald Pohl cut the rations in half. To stay alive, some inmates resorted to cannibalism, particularly during the winter months when other sustenance such as grass and sand was scarce. A black market of stolen meat emerged. Allegedly, “meat” came from dying inmates. Cannibalism became so rampant that extremely ill prisoners feared sleeping, afraid others might remove chunks of their flesh.

Mauthausen guards had nothing but time to come up with the most horrific ways to torture the prisoners. Sometimes they ordered them to pick strawberries in a field and then shot them…saying they were trying to escape. Concentration camp leaders also threw prisoner’s hats near the structure perimeters and shot whoever tried to retrieve their belongings. Barbed-wire fencing surrounded Mauthausen. The guards loved dangling “freedom” in front to the prisoners, or at least saying that the prisoners were trying to escape. Some inmates ended their own lives by throwing themselves against the fence. That didn’t usually end their lives instantly. The prisoner would just hang there, stuck in the wire, for days until they finally died.

Mauthausen was finally liberated when World War II ended in 1945, but many of the inmates never received  justice. They died before help arrived. The Austrian concentration camp claimed about 100,000 lives and thousands more were lost after their release. Allied soldiers didn’t understand the gravity of the situation when they arrived in Mauthausen. They were trying to help when they threw chocolate to the starving inmates. Chocolate has lots of calories, and is often given as a source of energy, but many of the inmates died, because their bodies could no longer digest solids. I can’t imagine the horror the soldiers must have felt, knowing that in trying to help, they had inadvertently caused the death of these poor prisoners. The camp was liberated on that day in 1945, but the terror that was daily life in Mauthausen will never be forgotten.

justice. They died before help arrived. The Austrian concentration camp claimed about 100,000 lives and thousands more were lost after their release. Allied soldiers didn’t understand the gravity of the situation when they arrived in Mauthausen. They were trying to help when they threw chocolate to the starving inmates. Chocolate has lots of calories, and is often given as a source of energy, but many of the inmates died, because their bodies could no longer digest solids. I can’t imagine the horror the soldiers must have felt, knowing that in trying to help, they had inadvertently caused the death of these poor prisoners. The camp was liberated on that day in 1945, but the terror that was daily life in Mauthausen will never be forgotten.

During his reign, Hitler was determined to rid the world of those people he decided were of an inferior race…basically anyone who was not blonde haired, blue-eyed, and fair skinned. It was a seriously strange idea considering that Hitler had dark hair, and it is rumored that Hitler may have had both Jewish and African ancestry. I don’t suppose he would have liked knowing that much, or maybe he knew and didn’t care.

During his reign, Hitler was determined to rid the world of those people he decided were of an inferior race…basically anyone who was not blonde haired, blue-eyed, and fair skinned. It was a seriously strange idea considering that Hitler had dark hair, and it is rumored that Hitler may have had both Jewish and African ancestry. I don’t suppose he would have liked knowing that much, or maybe he knew and didn’t care.

Hitler had a plan in mind to create the “perfect” race. His plan was two-fold. Most people know about the Holocaust, and the mass killing of Jews, Gypsies, and other “undesirable” races, by starvation, beatings, and most notably, the gas chambers. It is not known exactly how many people were killed, but the number is estimated at 6 million Jews, and as many as 11 million other groups. It was horrific, but it was not the only plan Hitler had.

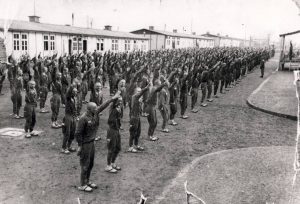

His other plan was the Lebensborn, which translates as “wellspring of life” or “fountain or life.” The Lebensborn project was one in which women…who were of the Aryan race, a historical race concept which emerged in the period of the late 19th century and mid-20th century to describe people of Indo-European heritage as a racial grouping. Heinrich Himmler founded the Lebensborn project on December 12, 1935, the same year the Nuremberg Laws outlawed intermarriage with Jews and others who were deemed inferior. In the beginning, the Lebensborn children were taken to SS nurseries. But in order to create a “super-race,” the SS transformed these nurseries into “meeting places” for “racially pure” German women who wanted to meet and have children with SS officers. The idea was that they were doing something great for “the cause.” The children born in the Lebensborn nurseries were then taken by the SS. The Lebensborn provided support for expectant mothers, we or unwed, by providing a home and the means to have their children in safety and comfort. For decades, Germany’s birthrate had been decreasing, and Himmler’s goal was to reverse the decline and increase the Germanic/Nordic population of Germany to 120 million. Himmler encouraged SS and Wermacht officers to have children with Aryan women. He believed Lebensborn children would grow up to lead a Nazi-Aryan nation. Once the children were born, the woman had the choice to marry the SS officer father, or give the child up for adoption. She was not allowed to keep the child on her own, and once she entered the Lebensborn she could not leave until the child was delivered.

Any children who were born with any defects were immediately put to death. The program had no room for any special-needs children. The children who were given up by the mothers, were usually kept at the Lebensborn for about a year before they were made available for adoption, and then only to SS or Wermacht soldiers families or members of the Nazi party. During their time in the SS nursery, they were named by Himmler. The whole purpose of this society (Registered Society Lebensborn – Lebensborn Eingetragener Verein) was to offer to young girls who were deemed “racially pure” the possibility to give birth to a child in secret. The child was then given to the SS organization which took charge in the child’s education and adoption. Both mother and father needed to pass a “racial purity” test. Blond hair and blue eyes were preferred, and family lineage had to be traced back at least three generations. Of all the women who applied, only 40 percent passed the racial purity test and were granted admission to the Lebensborn program. The majority of mothers were unmarried, 57.6 percent until 1939, and about 70 percent by 1940.

One of the most horrible sides of the Lebensborn policy was the kidnapping of children “racially good” in the eastern occupied countries after 1939. Some of these children were orphans, but it is well documented that many were stolen from their parents’ arms. These kidnappings were organized by the SS in order to take children by force who matched the Nazis’ racial criteria…blond hair and blue or green eyes. Thousands of children were taken to the Lebensborn centers in order to be “Germanized.” Up to 100,000 children may have

been stolen from Poland alone. In these centers, everything was done to force the children to reject and forget their birth parents. The SS nurses were told to persuade the children that they were deliberately abandoned by their parents. The children who refused the Nazi education were often beaten. Most of those who rejected Nazi principles were transferred to concentration camps, usually in Kalish in Poland, and exterminated. The others were adopted by SS families. The whole Lebensborn program was twisted. It was like growing machines who would believe and do as they were told, which is what they thought the children would grow up to do.

been stolen from Poland alone. In these centers, everything was done to force the children to reject and forget their birth parents. The SS nurses were told to persuade the children that they were deliberately abandoned by their parents. The children who refused the Nazi education were often beaten. Most of those who rejected Nazi principles were transferred to concentration camps, usually in Kalish in Poland, and exterminated. The others were adopted by SS families. The whole Lebensborn program was twisted. It was like growing machines who would believe and do as they were told, which is what they thought the children would grow up to do.

Being Jewish during the Holocaust meant doing whatever it took to survive. For some, that means hiding in walls or changing one’s identity, then so be it. Still, there were other Jews who had no way of doing either of these things, so they had to make due with what they had. The path to freedom and life was a difficult one, no matter what path they chose. There were close calls, starvation, fear, and a lot of quiet. Two families decided that they had no choice, but to take refuge in a hayloft over a pigsty offered by the owner, Francisca Halamajowa, a kindly Polish Catholic woman, and her daughter, Helena, who protected these families.

Being Jewish during the Holocaust meant doing whatever it took to survive. For some, that means hiding in walls or changing one’s identity, then so be it. Still, there were other Jews who had no way of doing either of these things, so they had to make due with what they had. The path to freedom and life was a difficult one, no matter what path they chose. There were close calls, starvation, fear, and a lot of quiet. Two families decided that they had no choice, but to take refuge in a hayloft over a pigsty offered by the owner, Francisca Halamajowa, a kindly Polish Catholic woman, and her daughter, Helena, who protected these families.

The Malkin and Kinder families went into hiding in 1942, just before the town’s Jewish ghetto was liquidated, but unfortunately, after 4 year old Fay Malkin’s father and others were killed in an old brick factory nearby. Years later in 2011, Fay Malkin told of the heroic acts of Halamajowa. Fay Malkin almost died shortly before her 5th birthday, while hiding in that hayloft. She told the Holocaust remembrance gathering at UJA-Federation of New York on May 3rd: “Hitler didn’t win, we’re here.” Malkin tells of the 20 months that the family and two other families stayed hidden in order to stay alive…and to protect their protectors, who would have also lost their lives if they were caught.

The families worried that 4-year-old Fay would give them away with her crying. The little girl promised not to cry, but that is really a lot to ask of a little girl. Malkin couldn’t control herself once in the hayloft. After trying many other approaches, the adults finally made the excruciating decision to poison little Fay in order to save the rest. Malkin would have almost certainly been killed, if they were discovered. Malkin said her memory of the incident is faint, but she remembers pushing out the pill put in her mouth. Just before she was put in a bag to be buried, a doctor who was among those hiding felt a slight pulse. She was saved. “I became the miracle child,” she said. Having lived with the story her whole life, Fay smiled when she said that her crying after that was controlled by pillows. The families were saved, not only because of the kindness and courage of their fellow townspeople, but by the miracle of a little child that didn’t die. I realize that the fact that little Fay Malkin lived through the attempted poisoning may not seem like something that saved the families, but in reality, how could they have lived with themselves? Yes, they would have been alive, but they would have been almost as bad as the Nazis who were trying to kill them.

The Malkin family lived in Sokal, then part of Poland…now in Ukraine. Before World War II, there were 6,000 Jews in Sokal. By the end of the war, only about 30 had survived, and half of them were sheltered by Halamajowa. For 20 months, the families stayed in that tiny hayloft…never daring to leave or even make a sound. Halamajowa and her daughter, Helena, risked their lives by feeding them surreptitiously and otherwise helping them, all the while disguising their actions from her neighbors and the occupying German army. In July 1944, the town was liberated by the Soviets. When the Malkin and Kindler families were finally able to come down from the hayloft, they learned that Halamajowa had also been sheltering another Jewish family in a hole dug under her kitchen floor. What these two women did was above and beyond expectation, and very brave.

Of course, most Jews never spoke of the experience. They didn’t want to get anyone in trouble, and their  protectors felt the same way. They didn’t trust the government, even with the war over. Halamajowa died in Russia in 1960…never having revealed her secrets. Nevertheless, in 1986 she was honored at Yad Vashem as a Righteous Gentile…a fitting title. In 2007, Malkin, Maltz, and several others from the hayloft and celler families, returned to Sokal. The trip was part of a film project that led to No. 4 Street of Our Lady. A basis for the film was the diary kept by Fay’s cousin, Moshe Maltz. Malkin said it was important but highly emotional going back to Sokal, especially seeing where her father was killed. Included in the group traveling there were the two granddaughters of Halamajowa, who now live in Connecticut. I’m sure it was very emotional.

protectors felt the same way. They didn’t trust the government, even with the war over. Halamajowa died in Russia in 1960…never having revealed her secrets. Nevertheless, in 1986 she was honored at Yad Vashem as a Righteous Gentile…a fitting title. In 2007, Malkin, Maltz, and several others from the hayloft and celler families, returned to Sokal. The trip was part of a film project that led to No. 4 Street of Our Lady. A basis for the film was the diary kept by Fay’s cousin, Moshe Maltz. Malkin said it was important but highly emotional going back to Sokal, especially seeing where her father was killed. Included in the group traveling there were the two granddaughters of Halamajowa, who now live in Connecticut. I’m sure it was very emotional.

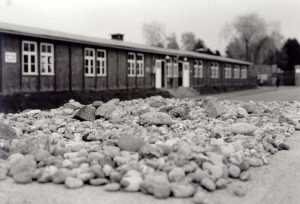

The Neuengamme concentration camp was established in December 1938, and used by the Nazis as a forced labor camp from December 13, 1938 to May 4, 1945, when it was liberated by British troops. At the time of its liberation, about half of the approximately 106,000 Jews held there over time had died. Neuengamme was located on the Elbe river, near Hamburg, Germany. One hundred inmates who were transferred from Sachsenhausen concentration camp, were forced to build the Neuengamme concentration camp. It was established around an empty brickworks in Hamburg-Neuengamme. The bricks produced there were to be used for the “Fuehrer buildings” part of the National Socialists’ redevelopment plans for the river Elbe in Hamburg.

The Neuengamme concentration camp was established in December 1938, and used by the Nazis as a forced labor camp from December 13, 1938 to May 4, 1945, when it was liberated by British troops. At the time of its liberation, about half of the approximately 106,000 Jews held there over time had died. Neuengamme was located on the Elbe river, near Hamburg, Germany. One hundred inmates who were transferred from Sachsenhausen concentration camp, were forced to build the Neuengamme concentration camp. It was established around an empty brickworks in Hamburg-Neuengamme. The bricks produced there were to be used for the “Fuehrer buildings” part of the National Socialists’ redevelopment plans for the river Elbe in Hamburg.

The prisoners worked on the construction of the camp and brickmaking. The bricks were used for regulating the flow of the Dove-Elbe river and the building of a branch canal. The prisoners were also  used to mine the clay used to make the bricks. That reminds me of the Jews in Egypt who were forced to build the pyramids. In 1940, the population of the camp was 2,000 prisoners, with a proportion of 80% German inmates among them. Between 1940 and 1945, more than 95,000 prisoners were incarcerated in Neuengamme. On April 10th, 1945, the number of prisoners in the camp itself was 13,500. Over the years that Neuengamme was open, it is estimated that 103,000 to 106,000 people were held there. We may never really know, because they didn’t keep clear records of all the people who went through the camps.

used to mine the clay used to make the bricks. That reminds me of the Jews in Egypt who were forced to build the pyramids. In 1940, the population of the camp was 2,000 prisoners, with a proportion of 80% German inmates among them. Between 1940 and 1945, more than 95,000 prisoners were incarcerated in Neuengamme. On April 10th, 1945, the number of prisoners in the camp itself was 13,500. Over the years that Neuengamme was open, it is estimated that 103,000 to 106,000 people were held there. We may never really know, because they didn’t keep clear records of all the people who went through the camps.

From 1942 on, the inmates were forced to work in the Nazi armament production. At first, the work was performed in the Neuengamme workshops, but soon it was decided to transfer the prisoners to the armaments factories in the surroundings areas. At the end of the war, the prisoners of Neuengamme were spread all over northern Germany. As the Allied troops advanced, hundreds of inmates were forced to dig antitank ditches. In many large north German cities, The prisoners were also require to clear rubble and removed corpses after bombing raids. There were 96 sub-camps, 20 of them for women. In early spring 1945, more than 45,000 inmates were working for the Nazi industry. A third of the women were forced to be among a part of the Nazi  industry workforce. By this time, the internal population of Neuengamme was 13,500, which made it completely overcrowded. The estimated number of victims in Neuengamme is approximately 56,000. Thousands of inmates were hanged, shot, gassed, killed by lethal injection or transferred to the death camps Auschwitz and Majdanek. As the war neared its end, the SS decided to evacuate Neuengamme. They had hoped to avoid having them liberated…probably hoping to regroup further north. This was the start of one of the worst death marches of the war. During these death marches, approximately 10,000 inmates perished by shootings or simply starvation. Nevertheless, the Allies won this war, and then they went in and liberated the prisoners of the many death camp.

industry workforce. By this time, the internal population of Neuengamme was 13,500, which made it completely overcrowded. The estimated number of victims in Neuengamme is approximately 56,000. Thousands of inmates were hanged, shot, gassed, killed by lethal injection or transferred to the death camps Auschwitz and Majdanek. As the war neared its end, the SS decided to evacuate Neuengamme. They had hoped to avoid having them liberated…probably hoping to regroup further north. This was the start of one of the worst death marches of the war. During these death marches, approximately 10,000 inmates perished by shootings or simply starvation. Nevertheless, the Allies won this war, and then they went in and liberated the prisoners of the many death camp.

While looking at some historic photos, I came across one that was both intriguing, and sad. The title of the photograph was as intriguing as the photograph itself. Shoes on the Danube Banksdepicts a memorial in Budapest, Hungary that was conceived by film director Can Togay. The memorial sits on the east and of the Danube River. Togay worked with sculptor Gyula Pauer to create a memorial to honor the Jews who were killed by fascist Arrow Cross militiamen in Budapest during World War II.

While looking at some historic photos, I came across one that was both intriguing, and sad. The title of the photograph was as intriguing as the photograph itself. Shoes on the Danube Banksdepicts a memorial in Budapest, Hungary that was conceived by film director Can Togay. The memorial sits on the east and of the Danube River. Togay worked with sculptor Gyula Pauer to create a memorial to honor the Jews who were killed by fascist Arrow Cross militiamen in Budapest during World War II.

As I looked at the picture of many pairs of shoes, the magnitude of what had happened there, and exactly what I was looking at hit me. These shoes were not just shoes, they were people…innocent people, who lined up and shot for no other reason than that they were Jewish. These people were told to remove their shoes, and then they were shot. Their lifeless bodies fell into the river and were swept downstream. There was no funeral, no burial…despite the traditions that are set up for Jewish burial. Of course, I know that not every Jewish death can be handles in the Jewish traditions, but these people were murdered in such a way as to humiliate them, including the lack of a traditional burial.

The monument along the Danube River represents the lives of the people who were murdered, there is no way to really represent the people, because no one knows who they were, what they looked like, or even how many there were for sure, but rather the monument depicts their shoes left behind on the bank. It is the only real connection we can have to these victims of such horrible hatred. The brutal treatment of the approximately 3,500 people, 800 of them Jews, and the rest accused of Jewish activities, is beyond horrid. These people were forced to strip naked on the banks of the Danube and face the river. Then, a firing squad shot the prisoners at close range in the back so that they fell into the river to be washed away.

The monument is located on the Pest side of the Danube Promenade in line with where Zoltan Street would meet the Danube if it continued that far, about 980 feet south of the Hungarian Parliament and near the Hungarian Academy of Sciences…between Roosevelt Square and Kossuth square. The sculptor created sixty pairs of period-appropriate shoes out of iron. The shoes are attached to the stone embankment, and behind them lies a 131 foot long, 27 inch high stone bench. At three points are cast iron signs, with the following text in Hungarian, English, and Hebrew: “To the memory of the victims shot into the Danube by Arrow Cross militiamen in 1944–45. Erected 16 April 2005.”

Most of the murders along the edge of the River Danube took place around December 1944 and January 1945, when the members of the Arrow Cross Party police (“Nyilas”) took as many as 20,000 Jews from the newly established Budapest ghetto and executed them along the river bank. There were, of course, some survivors who managed to make it out, and lived to tell their stories. On of those Was Tommy Dick, who wrote the book, “Getting Out Alive.” I have not read the book yet, but after seeing this memorial, I will be reading it very soon.

There were heroes in Budapest too. Valdemar Langlet, head of the Swedish Red Cross in Budapest, with his wife Nina, and later the diplomat Raoul Wallenberg and 250 coworkers were working around the clock to save the Jewish population from being sent to Nazi concentration camps. This group later grew in number to approximately 400. Lars and Edith Ernster, Jacob Steiner, and many others were housed at the Swedish Embassy in Budapest and 32 other buildings throughout the city which Wallenberg had rented and declared as extraterritorially Swedish to try to safeguard the residents. Italian Giorgio Perlasca did the same, sheltering Jews in the Spanish Embassy.

On the night of January 8, 1945, an Arrow Cross execution brigade forced all the inhabitants of the building on  Vadasz Street to the banks of the Danube. At midnight, Karoly Szabo and 20 policemen with drawn bayonets broke into the Arrow Cross house and rescued everyone. Among those saved were Lars Ernster, who fled to Sweden and became a member of the board of the Nobel Foundation from 1977 to 1988, and Jacob Steiner, who fled to Israel and became a professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Steiner’s father had been shot dead by Arrow Cross militiamen 25 December 1944, and fell into the Danube. His father had been an officer in World War I and spent four years as a prisoner of war in Russia. These were horrific murders, and after looking at the pictures of this memorial and reading about the horrible murders, my mind cannot unsee the images it has conjured up of this atrocity.

Vadasz Street to the banks of the Danube. At midnight, Karoly Szabo and 20 policemen with drawn bayonets broke into the Arrow Cross house and rescued everyone. Among those saved were Lars Ernster, who fled to Sweden and became a member of the board of the Nobel Foundation from 1977 to 1988, and Jacob Steiner, who fled to Israel and became a professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Steiner’s father had been shot dead by Arrow Cross militiamen 25 December 1944, and fell into the Danube. His father had been an officer in World War I and spent four years as a prisoner of war in Russia. These were horrific murders, and after looking at the pictures of this memorial and reading about the horrible murders, my mind cannot unsee the images it has conjured up of this atrocity.

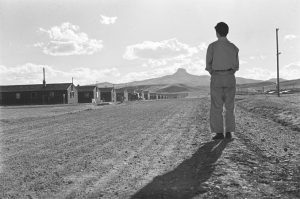

In the middle of a war, the people of a nation become concerned about anyone who might potentially be the enemy, especially if they are living inside the country’s borders. It is really a natural reaction to enemy personnel. After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the United states became quite concerned about the Japanese immigrants in our country, whether they were here legally or not. Much of the immigration to the United States from Japan began in 1884, when thousands of Japanese arrived in Hawaii to work the sugar cane fields. In the wake of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which drastically restricted Chinese immigration, Japanese people began arriving and began to prosper and started small businesses or became farmers. Most of them settled along the West Coast, meaning roughly 13,000 people of Japanese descent lived in the Intermountain West prior to World War II. The attack on Pearl Harbor, heightened the level of concern about those people.

In the middle of a war, the people of a nation become concerned about anyone who might potentially be the enemy, especially if they are living inside the country’s borders. It is really a natural reaction to enemy personnel. After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the United states became quite concerned about the Japanese immigrants in our country, whether they were here legally or not. Much of the immigration to the United States from Japan began in 1884, when thousands of Japanese arrived in Hawaii to work the sugar cane fields. In the wake of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which drastically restricted Chinese immigration, Japanese people began arriving and began to prosper and started small businesses or became farmers. Most of them settled along the West Coast, meaning roughly 13,000 people of Japanese descent lived in the Intermountain West prior to World War II. The attack on Pearl Harbor, heightened the level of concern about those people.

It was decided that, because their loyalties could not positively be confirmed, the Japanese immigrants needed to be rounded up and put in concentration camps. I suppose this might have seemed similar to what the Germans did to the Jewish people, but the Japanese people were not murdered in the camps, like the Jews were. And so it came to be that the people of Japanese descent from Oregon, Washington and California were incarcerated at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Park County, Wyoming, by the executive order of President Franklin Roosevelt. The prisoners were held at the camp from August 12, 1942 to November 10, 1945, which was actually two months after the end of the war with Japan. The camp was populated with 10,000 people at its largest, making it the third largest town in the state at the time.

I have tried to imagine what it must have been like for those Japanese immigrants to be held in the Heart Mountain Relocation Center for as much as 2 years and 3 months. Of course, the illegal immigrants of our time immediately came to my mind, but there is a difference between these people and the illegal immigrants of today. These people were here legally, and most of them had already become citizens. Unfortunately, that did not calm the worried minds of the rest of the people of the United States. Our nation had been attacked, and the attackers looked just like the Japanese immigrants. Precautions had to be taken. I’d like to think that if it were me, in that position, that I would understand why this was happening, but I’m not so sure I would. After all, these people were not criminals. They were hard working Americans, and yet they were for a time…the enemy, or possibly the enemy.

Unfortunately, like many prior immigrant groups, the Japanese faced discrimination. Things aren’t always fair, and people aren’t always treated properly. Starting in the early 20th century, Japanese immigrants, as well as Chinese immigrants, were targeted by Alien Land Laws in western states including Wyoming. These laws prevented the Asian immigrants from buying land. In 1924, the United States Congress passed the Asian Exclusion Act, which all but cut off new immigration from Asia. In response, Japanese Americans formed organizations such as the Japanese American Citizens’ League to help address their shared challenges. Despite  the attempts of Japanese Americans to fit in, some people expressed ongoing skepticism regarding the place of Asians in American society.

the attempts of Japanese Americans to fit in, some people expressed ongoing skepticism regarding the place of Asians in American society.

The Heart Mountain facility consisted of 450 barracks, each containing six apartments, when the first internees arrived on August 12, 1942. The largest apartments were simply single rooms measuring 24 feet by 20 feet. The barracks were covered with tar paper. While each unit was eventually outfitted with a potbellied stove, none had bathrooms. The people all used shared latrines. None of the apartments had kitchens. The residents ate their meals in mess halls. When the people first arrived, a barbed-wire fence to surround the camp was not yet complete. The internees protested the construction of this barrier and caused further work to be delayed. In November 1942, they submitted a petition containing 3,000 signatures to the War Relocation Authority (WRA) Director Dillon Meyer. The fence was completed by December, however, and further emphasized the sense of confinement among the internees. Shortly after the construction of the fence, 32 boys were arrested for sledding in the hills beyond the boundary. In response to the perceived overreaction on the part of the camp administration, Rikio Tomo, a Heart Mountain internee, placed an editorial in the Heart Mountain Sentinel asking for clarification about the internees’ citizenship status and constitutional freedoms. Schools were built at Heart Mountain, including a high school, to accommodate the children. These schools served students from elementary school through high school. Roughly 1500 students attended Heart Mountain High School, which included grades 8-12.

The internees provided most of the labor required to run the Heart Mountain camp, while WRA administrators oversaw its general operations. Wages ranged from $12 per month for unskilled labor to $19 per month for skilled labor, including teachers for the schools and doctors in the camp hospitals. In addition, Heart Mountain internees also worked as manual laborers on farms and ranches in Wyoming and nearby states from Nebraska to Oregon. The WRA administrators encouraged activities emphasizing American civics, such as scouting and adult English classes, as part of what they saw as an Americanization process. Committees composed initially of American-born internees provided much of the day-to-day governance of the camps. While these groups provided some measure of self-determination, they disrupted the generational hierarchy. American-born adults in their 20s and 30s were given a higher political status within the camps than their Japanese-born parents.

In 1943, General George Marshall approved the creation of the Japanese-American combat unit. As a result of the low turnout, the War Department extended the draft to the camps. It was decided that while they were not free to go where they chose, these people were needed to serve their country, so a draft was instituted. After they were drafted into the U.S. Army, soldiers from Heart Mountain occasionally returned to visit their families who were still held there. Somehow that doesn’t seem quite fair to me, and many of the prisoners agreed. They thought they should have been given their constitutional rights back before they were drafted. The organization of draft resistance distinguished Heart Mountain from the other relocation centers. The plan, which was given the endorsement of President Roosevelt, was to create an all-Japanese regiment, consisting of soldiers from a previously existing Hawaiian unit and volunteers from the camps. The response from within the camps fell far short of expectations, partly because of a loyalty questionnaire distributed by the WRA. The WRA form was used to determine eligibility for military service and permanent leave. Many of the questions were considered intrusive by prisoners. Others were not as straightforward as the WRA probably intended. Instead of serving as a neutral tool to determine someone’s suitability for service, the questionnaire further alienated many the men. To me it seems that the WRA was somehow not aware of how racist the entire situation really was. For example, question 27 asked about a person’s willingness to serve in the military. For

prisoners who felt service should be contingent upon the restoration of constitutional rights to all Japanese Americans, a simple yes or no answer was insufficient. In each of the camps, the draft became a divisive issue. While some prisoners felt military service was an opportunity to exemplify patriotism, others felt that constitutional rights should be restored before agreeing to mandatory service. I doubt if the situation would have ever really been resolved, except that the war ended.

prisoners who felt service should be contingent upon the restoration of constitutional rights to all Japanese Americans, a simple yes or no answer was insufficient. In each of the camps, the draft became a divisive issue. While some prisoners felt military service was an opportunity to exemplify patriotism, others felt that constitutional rights should be restored before agreeing to mandatory service. I doubt if the situation would have ever really been resolved, except that the war ended.

Kristallnacht, translated “Crystal Night,” referred to as the Night of Broken Glass, was an atrocious pogrom against Jews throughout Nazi Germany that took place on November 9–10, 1938. It was carried out by Sturmabteilung (SA) paramilitary forces and civilians. The German authorities looked on without intervening as the mobs tore through the towns. The attacks were said to be retaliation for the assassination of the Nazi German diplomat Ernst vom Rath by Herschel Grynszpan, a seventeen year old German-born Polish Jew living in Paris. I guess I don’t understand why the act of one person should cost the lives of so many.

Kristallnacht, translated “Crystal Night,” referred to as the Night of Broken Glass, was an atrocious pogrom against Jews throughout Nazi Germany that took place on November 9–10, 1938. It was carried out by Sturmabteilung (SA) paramilitary forces and civilians. The German authorities looked on without intervening as the mobs tore through the towns. The attacks were said to be retaliation for the assassination of the Nazi German diplomat Ernst vom Rath by Herschel Grynszpan, a seventeen year old German-born Polish Jew living in Paris. I guess I don’t understand why the act of one person should cost the lives of so many.

The name Kristallnacht comes from the shards of broken glass that littered the streets after the windows of Jewish-owned stores, buildings, and synagogues were smashed. Of course, the carnage didn’t stop with the windows. Estimates of the number of fatalities caused by the pogrom have varied. Reports in 1938 estimated that 91 Jews were murdered during the attacks, but modern analysis of German scholarly sources by historians such as Sir Richard Evans puts the number much higher. It also includes deaths  from post-arrest maltreatment and subsequent suicides as well, and puts the death toll into the hundreds. Additionally, 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and incarcerated in concentration camps. The numbers of those killed there are unknown, but we can easily imagine based on what we know of the Holocaust.

from post-arrest maltreatment and subsequent suicides as well, and puts the death toll into the hundreds. Additionally, 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and incarcerated in concentration camps. The numbers of those killed there are unknown, but we can easily imagine based on what we know of the Holocaust.

Breaking windows wasn’t enough for these mobs either. Jewish homes, hospitals, and schools were ransacked, as the attackers demolished buildings with sledgehammers. The rioters destroyed 267 synagogues throughout Germany, Austria, and the Sudetenland, and over 7,000 Jewish businesses were either destroyed or damaged. The British historian Martin Gilbert wrote that no event in the history of German Jews between 1933 and 1945 was so widely reported as it was happening, and the accounts from the foreign journalists working in Germany sent shock waves around the world. At that time it was still hard to believe that mobs of lawless people could  exist, but that was 80 years ago. These days we have no problem believing it, because these actions are almost commonplace.

exist, but that was 80 years ago. These days we have no problem believing it, because these actions are almost commonplace.

The British newspaper The Times wrote at the time: “No foreign propagandist bent upon blackening Germany before the world could outdo the tale of burnings and beatings, of blackguardly assaults on defenseless and innocent people, which disgraced that country yesterday.” Kristallnacht was followed, of course, by additional economic and political persecution of Jews, and it is viewed by historians as part of Nazi Germany’s broader racial policy, and the beginning of the Final Solution and The Holocaust.

The horrors of the Nazis were many, but the worst were what they did to the Jewish people. The gas chambers and the labor camps, experimentation and beatings, were horrible, and this only names a few of the things they did. Hitler was intent on killing as many Jews as he could, and he didn’t care how it got done, as long as it got done. One of the worst, in fact the second worst event of World War II, exceeded only by the 1941 Odessa massacre. The Aktion Erntefest, which translates to Operation Harvest Festival was the murder of 42,000 Jews at the same time. How anyone could call something like that a “festival” is beyond me.

The horrors of the Nazis were many, but the worst were what they did to the Jewish people. The gas chambers and the labor camps, experimentation and beatings, were horrible, and this only names a few of the things they did. Hitler was intent on killing as many Jews as he could, and he didn’t care how it got done, as long as it got done. One of the worst, in fact the second worst event of World War II, exceeded only by the 1941 Odessa massacre. The Aktion Erntefest, which translates to Operation Harvest Festival was the murder of 42,000 Jews at the same time. How anyone could call something like that a “festival” is beyond me.

The action was set in motion by the SS and Order Police, and the Ukrainian Sonderdienst formations in the General Government territory of occupied Poland. The murder of the Jewish laborers in concentration camp Lublin/Majdanek and the forced-labor camps Trawniki and Poniatowa was an unfathomable atrocity. The murders were  performed in retaliation for the uprisings at the Treblinka and Sobibor killing centers and the Warsaw, Bialystok, and Vilna ghettos that had led to increased concerns about Jewish resistance. To prevent further resistance, SS chief Heinrich Himmler ordered the killing of surviving Jews in the Lublin District of German-occupied Poland. Most of the remaining Jews were employed in forced-labor projects and were concentrated in the Trawniki…at least 4,000 people, Poniatowa…at least 11,000 people, and Majdanek…about 18,000 people. They were killed at Majdanek, near Lublin on November 3rd and 4th, 1943.

performed in retaliation for the uprisings at the Treblinka and Sobibor killing centers and the Warsaw, Bialystok, and Vilna ghettos that had led to increased concerns about Jewish resistance. To prevent further resistance, SS chief Heinrich Himmler ordered the killing of surviving Jews in the Lublin District of German-occupied Poland. Most of the remaining Jews were employed in forced-labor projects and were concentrated in the Trawniki…at least 4,000 people, Poniatowa…at least 11,000 people, and Majdanek…about 18,000 people. They were killed at Majdanek, near Lublin on November 3rd and 4th, 1943.  The SS shot them in large prepared ditches outside the camp fence near the crematorium. Jews from other labor camps in the Lublin area were also taken to Majdanek and shot. Loud music was played through speakers at both Majdanek and Trawniki to drown out the noise of the mass shootings. The killing at Majdanek was the largest single-day, single-location massacre during the Holocaust.

The SS shot them in large prepared ditches outside the camp fence near the crematorium. Jews from other labor camps in the Lublin area were also taken to Majdanek and shot. Loud music was played through speakers at both Majdanek and Trawniki to drown out the noise of the mass shootings. The killing at Majdanek was the largest single-day, single-location massacre during the Holocaust.

On the orders of Christian Wirth and Jakob Sporrenberg, the approximately 42,000 to 43,000 Jews were gunned down, and dumped in the ditches. It was not only retaliation for actions of rebellion, but probably also a way to deter any further resistance among the other Jews. The fact that the Jews were viewed an non-humans, made it easier to kill them, I suppose, but the killing were beyond horrible to most decent people, but to the Nazis it was almost considered sport or at the very least fun. To anyone who values human life, it was totally horrific.

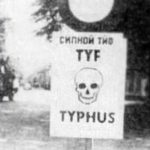

Heroes come in many forms, but few could be said to have been as sneaky as Eugene Lazowski, who was born Eugeniusz Slawomir Lazowski, in 1913 in Poland. His bravery was combined with genius, and in the end, he saved 8,000 Polish Jews at the height of the Holocaust. Lazowski saw the horrible way the Jews were treated, and he saw a way to help. Eugene Lazowski had just finished medical school when the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939. Typhus was spreading across the country. The disease was killing an average of 750 people a day. In an attempt to contain the disease, the Nazis increased their isolation and execution of Jews. Eugene joined the Polish Red Cross, but he was forbidden by the Nazis from treating Jewish patients. Nevertheless, under the cover of darkness, he sneaked into the Jewish ghetto and took care of the people there. Lazowski’s plan took an incredible amount of intellect, not to mention bravery. His life was on the line too. Lazowski created the illusion of an epidemic of a deadly disease, playing on the deep fears of the Nazis.

Heroes come in many forms, but few could be said to have been as sneaky as Eugene Lazowski, who was born Eugeniusz Slawomir Lazowski, in 1913 in Poland. His bravery was combined with genius, and in the end, he saved 8,000 Polish Jews at the height of the Holocaust. Lazowski saw the horrible way the Jews were treated, and he saw a way to help. Eugene Lazowski had just finished medical school when the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939. Typhus was spreading across the country. The disease was killing an average of 750 people a day. In an attempt to contain the disease, the Nazis increased their isolation and execution of Jews. Eugene joined the Polish Red Cross, but he was forbidden by the Nazis from treating Jewish patients. Nevertheless, under the cover of darkness, he sneaked into the Jewish ghetto and took care of the people there. Lazowski’s plan took an incredible amount of intellect, not to mention bravery. His life was on the line too. Lazowski created the illusion of an epidemic of a deadly disease, playing on the deep fears of the Nazis.

The plan came about in an unusual way. One day, a Polish soldier on leave begged Eugene and his colleague, Dr Stanislaw Matulewicz, to help him avoid returning to the warfront. I think there were many people who fought on the Nazi side of that era, who would give anything not to take part in what the Nazis were all about. Matulewicz had discovered that by injecting a healthy person with a vaccine of dead bacteria, that person would test positive for epidemic typhus without experiencing the symptoms. In an attempt to help the young solider fake a life-threatening illness, the doctors who had discovered that a dead strain of the Proteus OX19 bacteria in typhus would still lead to a positive test for the disease. Eugene realized that this could be used as a defense against the Nazis.

The plan came about in an unusual way. One day, a Polish soldier on leave begged Eugene and his colleague, Dr Stanislaw Matulewicz, to help him avoid returning to the warfront. I think there were many people who fought on the Nazi side of that era, who would give anything not to take part in what the Nazis were all about. Matulewicz had discovered that by injecting a healthy person with a vaccine of dead bacteria, that person would test positive for epidemic typhus without experiencing the symptoms. In an attempt to help the young solider fake a life-threatening illness, the doctors who had discovered that a dead strain of the Proteus OX19 bacteria in typhus would still lead to a positive test for the disease. Eugene realized that this could be used as a defense against the Nazis.

The two doctors hatched a secret plan to save about a dozen villages in the vicinity of Rozwadów and Zbydniów not only from forced labor exploitation, but also Nazi extermination. Lazowski began distributing the phony vaccine widely. Within two months, so many new (fake) cases were confirmed that Eugene successful  convinced his Nazi supervisors a typhus epidemic had broken out. The Nazis immediately quarantined areas with suspected typhus cases, including those with Jewish inhabitants. In 12 other villages, Eugene created safe havens for Jews through these quarantines. His work would eventually save 8,000 Jewish lives.

convinced his Nazi supervisors a typhus epidemic had broken out. The Nazis immediately quarantined areas with suspected typhus cases, including those with Jewish inhabitants. In 12 other villages, Eugene created safe havens for Jews through these quarantines. His work would eventually save 8,000 Jewish lives.

When the war ended, Eugene continued to practice medicine in Poland until he was forced to flee with his family to the United States. They settled in Chicago, where Eugene earned a medical degree from the University of Illinois. Decades later, he finally returned to Poland, where he received a hero’s welcome for saving those in desperate need of salvation through his unyielding love for humanity.