italy

When Switzerland found itself in the middle of an unusual heatwave, the Gauli Glacier melted enough to uncover the wreckage debris of an American World War II plane that crash-landed in the Bernese Alps 72 years ago. Now, when you hear about the crash of a plane, especially into a mountain or in this case, a glacier, you expect to find fatalities. Of course, this plane crashed a long time ago, and the authorities already knew the outcome of that crash. The people who found the plane in the ice, however, might not have. This plane, a C-53 Skytrooper Dakota had been traveling from Austria to Italy when it collided with the Gauli Glacier at an altitude of 10,990 feet on that fateful day.

When Switzerland found itself in the middle of an unusual heatwave, the Gauli Glacier melted enough to uncover the wreckage debris of an American World War II plane that crash-landed in the Bernese Alps 72 years ago. Now, when you hear about the crash of a plane, especially into a mountain or in this case, a glacier, you expect to find fatalities. Of course, this plane crashed a long time ago, and the authorities already knew the outcome of that crash. The people who found the plane in the ice, however, might not have. This plane, a C-53 Skytrooper Dakota had been traveling from Austria to Italy when it collided with the Gauli Glacier at an altitude of 10,990 feet on that fateful day.

It was November 19, 1946, and the plane carrying four crew members and eight passengers were enjoying their trip, when something went terribly wrong. When they hit the glacier, several people were injured, amazingly, there were no fatalities. Among the passengers were high-ranking United States service members traveling with relatives…four women and one 11-year-old girl. Now, they found themselves high up on a glacier, and it was likely very cold. They were stuck at the crash site for six days before rescuers found them and could

get to them. They were forced to drink snow water and ration chocolate bars to survive, but survive they did. Many times, survival at a crash site, if you survived the initial crash, is all about using common sense and keeping your wits about you. You have to take stock of your supplies and be willing to ration what you have. You can’t let anyone get out of control, because a panic could waste vital supplies. Water is the most vital of the supplies, because while the human body can go weeks without food, it can only live a few days without water. While it would seem that water on a glacier would be plentiful, it may not be so. You would have to chip away at the ice, and then melt it to drink. In addition, you have to get it warm, or you will risk the water causing Hypothermia. This particular group managed to do things right, or at least enough right to survive the six days while they waited for rescue. Once rescued, they went on with their lives feeling very blessed to be alive.

get to them. They were forced to drink snow water and ration chocolate bars to survive, but survive they did. Many times, survival at a crash site, if you survived the initial crash, is all about using common sense and keeping your wits about you. You have to take stock of your supplies and be willing to ration what you have. You can’t let anyone get out of control, because a panic could waste vital supplies. Water is the most vital of the supplies, because while the human body can go weeks without food, it can only live a few days without water. While it would seem that water on a glacier would be plentiful, it may not be so. You would have to chip away at the ice, and then melt it to drink. In addition, you have to get it warm, or you will risk the water causing Hypothermia. This particular group managed to do things right, or at least enough right to survive the six days while they waited for rescue. Once rescued, they went on with their lives feeling very blessed to be alive.

The snow, and later, ice covered the plane as the years went by, and it was very likely forgotten…until 2012 anyway, when three young people discovered the plane’s propeller on the glacier. They continued to observe the emerging plane and as the glacier continued to melt, the scene unfolded. Today, it reportedly looks like a

field covered in plane debris, and many people probably wonder how anyone managed to live through the initial crash…much less everyone. As the glacier melted, the plane slid down the mountainside and was expected to finally emerge at the bottom. In fact, much of the debris field might actually be caused by the melting ice.

field covered in plane debris, and many people probably wonder how anyone managed to live through the initial crash…much less everyone. As the glacier melted, the plane slid down the mountainside and was expected to finally emerge at the bottom. In fact, much of the debris field might actually be caused by the melting ice.

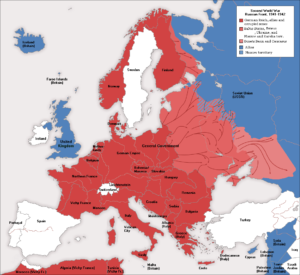

When countries choose sides in a war, there isn’t normally much chance that they will switch sides, but that is exactly what happened to Romania…and in fact, there were four countries that switched sides in that war, so maybe it isn’t so uncommon after all. At the start of the war Romania was allied and Poland and pro-British. They were trying to stay neutral, but that wasn’t easy. As the war progressed, Romania became more and more concerned about being overrun by the Soviet Union and the Fascist elements already in Romania. Finally, the decision was made to adopt a pro-German dictatorship and became an ‘affiliate state’ of the Axis Powers. The Romanian government signed the Tripartite Pact in November 1940. During the time that Romania supported the Axis powers, they supplied Nazi Germany and the Axis armies with oil, grain, and industrial products. Also, numerous train stations in the country, such as Gara de Nord in Bucharest, served as transit points for troops departing for the Eastern Front.

When countries choose sides in a war, there isn’t normally much chance that they will switch sides, but that is exactly what happened to Romania…and in fact, there were four countries that switched sides in that war, so maybe it isn’t so uncommon after all. At the start of the war Romania was allied and Poland and pro-British. They were trying to stay neutral, but that wasn’t easy. As the war progressed, Romania became more and more concerned about being overrun by the Soviet Union and the Fascist elements already in Romania. Finally, the decision was made to adopt a pro-German dictatorship and became an ‘affiliate state’ of the Axis Powers. The Romanian government signed the Tripartite Pact in November 1940. During the time that Romania supported the Axis powers, they supplied Nazi Germany and the Axis armies with oil, grain, and industrial products. Also, numerous train stations in the country, such as Gara de Nord in Bucharest, served as transit points for troops departing for the Eastern Front.

With all of this, Romania caught the eye of the Allies in 1943, and soon became a target for their aerial bombardment. One of the most notable air bombardments was the attack on the oil fields of Ploie?ti on August 1, 1943, known as Operation Tidal Wave. On April 4 and 15, 1944, Bucharest was subjected to intense Allied bombardment. On August 23, 1944, King Michael I removed the government of Ion Antonescu and declared Romanian support to the Allies. Then the Luftwaffe bombed the city Bucharest on August 24 and 25, 1944 in direct response to the Romania’s decision to switch sides. Some experts believe that by switching sides Romania helped shorten the war by several months. I’m sure that Romania was glad to be on the winning side of the war.

Romania was not the only nation to switch sides in Worls War II. They were Bulgaria, Finland, and Italy. Bulgaria also signed the Tripartite Pact in March of 1941, but Finland never signed it, but was nonetheless a co-belligerent on the side of the Axis Powers. Finland signed the Anti-Comintern Pact, an anti-communist agreement of mainly fascist powers, in November 1941. Italy had its own imperial ambitions, which were partly

based on the Roman Empire and similar to the German policy of lebensraum, which clashed with those of Britain and France. No matter wat their aspirations were, all of these nations decided that the ways of Germany and Hitler were simply not ways they could live with, so they switched sides, joined the Allied Nations, further weakened Hitler to the point of causing his demise.

based on the Roman Empire and similar to the German policy of lebensraum, which clashed with those of Britain and France. No matter wat their aspirations were, all of these nations decided that the ways of Germany and Hitler were simply not ways they could live with, so they switched sides, joined the Allied Nations, further weakened Hitler to the point of causing his demise.

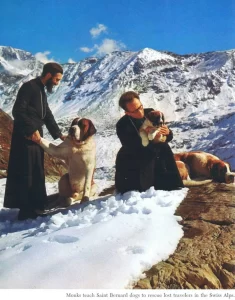

People have been fascinated with Saint Bernard dogs for years. There have been movies made about them, often portraying them as clumsy, drooling pests that “terrorize” homes by making massive messes. Saint Bernards might seem like they are big and clumsy, but for many years, they have been saving lives, and they weren’t clumsy about their work at all. In fact, they were experts at their work.

People have been fascinated with Saint Bernard dogs for years. There have been movies made about them, often portraying them as clumsy, drooling pests that “terrorize” homes by making massive messes. Saint Bernards might seem like they are big and clumsy, but for many years, they have been saving lives, and they weren’t clumsy about their work at all. In fact, they were experts at their work.

In the early 18th century some monks, who were living in the snowy and dangerous Saint Bernard Pass, which is a route through the Alps between Italy and Switzerland, kept these dogs to help them on their rescue missions after bad snowstorms. In fact, the Saint Bernard dogs got their name from the pass where the monks were located. Over a span of nearly 200 years, about 2,000 people, from lost children to Napoleon’s soldiers, were rescued because of the heroic dogs’ uncanny sense of direction and resistance to cold. Of course, there were changes in the dogs through crossbreeding, and finally the dogs became the amazing new breed they are today. While the dogs are amazing as rescue dogs, Saint Bernard dogs are also commonly seen in households today.

The dogs were trained to hunt for people who were lost, and when they found them, the dogs allegedly carried a small cask of liquor around their neck…although, this has not been documented for sure. Then, the dog would lay on top of the victim to keep them warm. Being lost in a snowstorm, often called “white death” could become a death sentence, because hypothermia would soon set in, and the victim would be lost. At a little more than 8,000 feet above sea level, the Great Saint Bernard Pass is a 49-mile route in the Western Alps. The pass is covered with snow for most of the year, and in fact, it is only snow free for a couple of months during the  summer. Throughout history, the route has been a treacherous one for many travelers. Of course, that didn’t stop people from trying to make the trek. An Augustine monk named Saint Bernard de Menthon founded a hospice and monastery around the year 1050, which is how Saint Bernard Pass came into being. Sometime between 1660 and 1670, the monks at Great Saint Bernard Hospice acquired their first Saint Bernards. These dogs were descendants of the mastiff style Asiatic dogs brought over by the Romans. The dogs were to be used as watchdogs and companions. The original Saint Bernards were quite a bit smaller in size, had shorter reddish brown and white fur, and a longer tail.

summer. Throughout history, the route has been a treacherous one for many travelers. Of course, that didn’t stop people from trying to make the trek. An Augustine monk named Saint Bernard de Menthon founded a hospice and monastery around the year 1050, which is how Saint Bernard Pass came into being. Sometime between 1660 and 1670, the monks at Great Saint Bernard Hospice acquired their first Saint Bernards. These dogs were descendants of the mastiff style Asiatic dogs brought over by the Romans. The dogs were to be used as watchdogs and companions. The original Saint Bernards were quite a bit smaller in size, had shorter reddish brown and white fur, and a longer tail.

Travel on the Saint Bernard Pass route was so dangerous, and at the turn of the century, servants used as guides were assigned to accompany travelers between the hospice and Bourg-Saint-Pierre, a municipality on the Swiss side. The trek was even treacherous for them, and by 1750, the guides were routinely accompanied by the dogs, whose broad chests helped to clear paths for travelers. While working with the dogs, the guides soon discovered that the dogs had a tremendous sense of smell, as well as their ability to discover people buried deep in the snow. Soon the dogs were sent out in packs of two or three alone to seek lost or injured travelers. Once they found a lost traveler, one dog would stay with the victim, while the other or others would go back to the hospice to bring help.

So good were these dogs at their work, that when Napoleon and his 250,000 soldiers crossed through the pass between 1790 and 1810, not one soldier lost his life. The soldiers’ chronicles tell of how many lives were saved by the dogs in what the army had named “the White Death.” So amazing were these dogs, that one, named Barry, that was particularly legendary, who lived in the monastery from 1800-1812, saved the lives of more than 40 people. In 1815, Barry’s body was put on exhibit at the Natural History Museum in Berne, Switzerland, where it remains today. Saint Bernard dogs have proven themselves to be a vital part of mountain rescue operations.

So good were these dogs at their work, that when Napoleon and his 250,000 soldiers crossed through the pass between 1790 and 1810, not one soldier lost his life. The soldiers’ chronicles tell of how many lives were saved by the dogs in what the army had named “the White Death.” So amazing were these dogs, that one, named Barry, that was particularly legendary, who lived in the monastery from 1800-1812, saved the lives of more than 40 people. In 1815, Barry’s body was put on exhibit at the Natural History Museum in Berne, Switzerland, where it remains today. Saint Bernard dogs have proven themselves to be a vital part of mountain rescue operations.

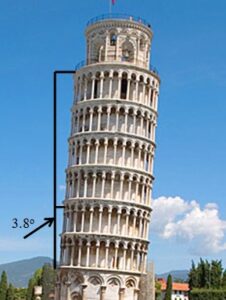

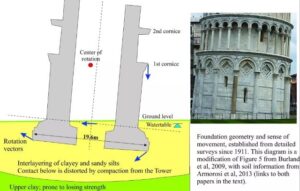

Many people think that the Leaning Tower of Pisa was once straight, and then gradually began to lean, but that is not the case at all. Nevertheless, the lean became problematic over time. Construction on the Leaning Tower began on August 9, 1173. The plan was for the tower to house the bells of the vast cathedral of the Piazza dei Miracoli, which means the “Place of Miracles” in English. The city of Pisa at that time was a major trading power and one of the richest cities in the world. The bell tower was designed to be the most magnificent tower Europe had ever seen. Work progressed…until the tower was just over three stories tall, and then it abruptly stopped for reasons unknown. There has been speculation as to why the construction was stopped. Some people think it may have been because of economic or political strife, but the consensus seems to be that the engineers may have noticed that even then, the tower had begun to sink down into the ground on one side.

Many people think that the Leaning Tower of Pisa was once straight, and then gradually began to lean, but that is not the case at all. Nevertheless, the lean became problematic over time. Construction on the Leaning Tower began on August 9, 1173. The plan was for the tower to house the bells of the vast cathedral of the Piazza dei Miracoli, which means the “Place of Miracles” in English. The city of Pisa at that time was a major trading power and one of the richest cities in the world. The bell tower was designed to be the most magnificent tower Europe had ever seen. Work progressed…until the tower was just over three stories tall, and then it abruptly stopped for reasons unknown. There has been speculation as to why the construction was stopped. Some people think it may have been because of economic or political strife, but the consensus seems to be that the engineers may have noticed that even then, the tower had begun to sink down into the ground on one side.

The tower sat unfinished for 95 years, which allowed the building to settle, and the new chief engineer tried to figure out a way to compensate for the tower’s visible lean by making the new stories slightly taller on the short side. In theory, that may have seemed like a viable solution, but when you add weight without addressing the problem that is causing the building to sink, you are fighting against yourself. By 1278, when the workers had reached the top of the seventh story, they were forced to stop construction again, because they realized that the southward tilt was now nearly three feet…even with the adjustments they had tried to make to compensate.

The frustrated Italian government, rather at its wits end, announced on February 27, 1964, that it would be accepting suggestions on how to save the renowned Leaning Tower of Pisa from collapse. By this time, the top of the 180-foot tower was hanging an astonishing 17 feet south of the base, and to make matters worse, studies showed that the tilt was increasing by a fraction every year. That may not seem like so much, but like the “straw that broke the camel’s back,” no one knew Exactly when the point would come when the tower could not be saved. That also meant that the tower was unsafe to allow people to come in, or at least it was perceived to be eminently unsafe, and when the experts warned that the medieval building…one of Italy’s top tourist attractions, was in serious danger of collapse in an earthquake or storm, something had to be done.

The Italian government began to reach out in earnest for proposals to save the Leaning Tower, and proposals came from all over the world, but it was not until 1999 that successful restorative work began. In recent years, the cause of the lean was finally determined to be that the tower’s lean was caused by the remains of an ancient river estuary located under the building. That information told them that a completely safe resolution was unlikely, and that straightening the tower was completely out of reach in its current location.

In 1990, the Italian government closed the Leaning Tower’s doors to the public out of safety concerns and began considering more drastic proposals to save the tower. Then, in 1992, in an effort to temporarily stabilize the building, plastic-coated steel tendons were built around the tower up to the second story. In 1993, a concrete foundation was built around the tower, adding counterweights on the north side. The use of these weights lessened the tilt by nearly an inch, bringing new hope to the people. Still, it was an eyesore, and in 1995, the commission overseeing the restoration sought to replace the unsightly counterweights with underground cables. The strange method to do this was that engineers froze the ground with liquid nitrogen in preparation for the removal of the counterweights. Unfortunately, this actually caused a dramatic increase in the lean and the project was called off. Finally, in 1999, engineers began a process of soil extraction under the north side that within a few months was showing positive effects. The soil was removed at a very slow pace, no more than a gallon or two a day, and a massive cable harness held the tower to avoid any sudden destabilization. Finally, it seemed that progress was being made. Within six months, the tilt had been reduced

by over an inch, and by the end of 2000, nearly a foot. Relieved, the Italian government was able to reopen the tower to the public in December 2001, after a foot-and-a-half reduction had been achieved. While this will not stop the continuing tilt, it is expected that those 18 inches will give another 300 years of life to the Leaning Tower of Pisa…an amazing feat indeed. The tower will have to be carefully monitored to ensure the safety of those who visit it every year, but for now, disaster has been averted.

by over an inch, and by the end of 2000, nearly a foot. Relieved, the Italian government was able to reopen the tower to the public in December 2001, after a foot-and-a-half reduction had been achieved. While this will not stop the continuing tilt, it is expected that those 18 inches will give another 300 years of life to the Leaning Tower of Pisa…an amazing feat indeed. The tower will have to be carefully monitored to ensure the safety of those who visit it every year, but for now, disaster has been averted.

On October 31, 1922, following the March on Rome, Benito Mussolini was appointed prime minister by King Victor Emmanuel III. With that appointment, he became the youngest individual to hold the office up to that time. Mussolini quickly got to work, removing all political opposition through his secret police and outlawing labor strikes. He, along with his followers consolidated power through a series of laws that transformed Italy into a one-party dictatorship. A short five years later, he had established dictatorial authority by both legal and illegal means and planned to create a totalitarian state.

On October 31, 1922, following the March on Rome, Benito Mussolini was appointed prime minister by King Victor Emmanuel III. With that appointment, he became the youngest individual to hold the office up to that time. Mussolini quickly got to work, removing all political opposition through his secret police and outlawing labor strikes. He, along with his followers consolidated power through a series of laws that transformed Italy into a one-party dictatorship. A short five years later, he had established dictatorial authority by both legal and illegal means and planned to create a totalitarian state.

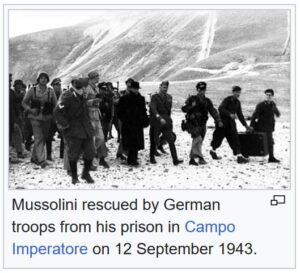

Still, as often happens, the people, good government officials, and of course, God made it clear that both fascist Italy and its dictator Benito Mussolini’s days were numbered by July 1943. So, after the successful Allied invasion of Sicily, the Italian government’s Grand Council delivered Mussolini a vote of no confidence. Shortly after that, King Vittorio Emanuele III replaced Mussolini as prime minister, and immediately had him arrested.

When Adolf Hitler heard of Mussolini’s arrest, he was furious. Hitler considered Mussolini to be his most powerful European ally, and Hitler began to make plans to rescue Mussolini. He brought in SS Major Otto Skorzeny, who was considered “the most dangerous man in Europe,” for the rescue mission. The Germans had  discovered that Mussolini was being held in a mountain ski resort 7,000 feet above sea level in the Abruzzo region. Due to the remoteness of the location, Skorzeny decided the only way to rescue Mussolini was to send in a dozen gliders with 108 commandos to do the job. The mission, dubbed Operation Eiche commenced on September 12, 1943. Along with the commandos, Skorzeny brought along an Italian general named Soleti. It was Soleti’s mission to create confusion among Mussolini’s guards, thereby giving the commandos time to get to Mussolini. While Soleti shouted orders at the confused guards, the commandos recaptured Mussolini without incident and flew him to a nearby Luftwaffe airfield, then to Hitler’s Wolf’s Lair headquarters in East Prussia.

discovered that Mussolini was being held in a mountain ski resort 7,000 feet above sea level in the Abruzzo region. Due to the remoteness of the location, Skorzeny decided the only way to rescue Mussolini was to send in a dozen gliders with 108 commandos to do the job. The mission, dubbed Operation Eiche commenced on September 12, 1943. Along with the commandos, Skorzeny brought along an Italian general named Soleti. It was Soleti’s mission to create confusion among Mussolini’s guards, thereby giving the commandos time to get to Mussolini. While Soleti shouted orders at the confused guards, the commandos recaptured Mussolini without incident and flew him to a nearby Luftwaffe airfield, then to Hitler’s Wolf’s Lair headquarters in East Prussia.

While Mussolini was free now, this would not be the victory Mussolini had hoped for. The Germans installed Mussolini as the head of a puppet regime called the Italian Socialist Republic in the town of Salo. The position wasn’t much more than symbolic. The German press portrayed the rescue as a daring feat of bravery…at the time, but in 2016, Italian author Vincenzo Di Michele researched the raid and concluded that it was likely enabled by Mussolini sympathizers in the Italian government. Mussolini could not be allowed to be free, even to run a puppet regime, and so the Allies began their hunt for him. On April 25, 1945, Allied troops were advancing into northern Italy, and the collapse of the Salò Republic was imminent. Mussolini and his mistress Clara Petacci attempted to escape to Switzerland, intending to board a plane and escape to Spain. Two days later on April 27th, they were stopped near the village of Dongo (Lake Como) by communist partisans named

Valerio and Bellini and identified by the Political Commissar of the partisans’ 52nd Garibaldi Brigade, Urbano Lazzaro. The next day, Mussolini and Petacci were both executed, along with most of the members of their 15-man train, primarily ministers and officials of the Italian Social Republic, in the small village of Giulino di Mezzegra by a partisan leader who used the name de guerre Colonnello Valerio (Not his real name, his real name remains unknown.)

Valerio and Bellini and identified by the Political Commissar of the partisans’ 52nd Garibaldi Brigade, Urbano Lazzaro. The next day, Mussolini and Petacci were both executed, along with most of the members of their 15-man train, primarily ministers and officials of the Italian Social Republic, in the small village of Giulino di Mezzegra by a partisan leader who used the name de guerre Colonnello Valerio (Not his real name, his real name remains unknown.)

Whenever a man-made reservoir is created, there is a possibility that a town, ranch, or some other building will be covered up, in the process. That applies everywhere really, because often towns, ranches, and such are built near rivers, and to make a man-made reservoir, you need to dam up a river. Of course, there are natural ways to make a reservoir, but whatever you do, there must be a water source somewhere nearby.

Whenever a man-made reservoir is created, there is a possibility that a town, ranch, or some other building will be covered up, in the process. That applies everywhere really, because often towns, ranches, and such are built near rivers, and to make a man-made reservoir, you need to dam up a river. Of course, there are natural ways to make a reservoir, but whatever you do, there must be a water source somewhere nearby.

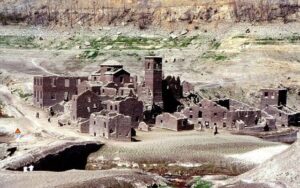

While making man-made reservoir is fairly common these days, it really wasn’t in medieval Italy or any other medieval times, but still, it wasn’t unheard of. Lake Vagli in Tuscany is a man-made reservoir, and like many other man-made reservoirs, it is hiding a secret. Below the surface lies the village of Fabbriche di Careggine, a medieval village founded around the year 1270 by blacksmiths in the area. The village existed for hundreds of years as a small mining community. All that ended in 1946, when a hydroelectric dam was built, which forced the evacuation of the village. At the time, there were still 150 people living in Fabbriche di Careggine. They moved to the nearby town of Vagli Sotto.

For whatever reason, the lake was drained in 1958, presumably to work on the dam. Whether it was then that the interest in the village grew, or not, the lake was drained again in 1974, 1983, and 1994…again for dam maintenance. On the last occasion, the draining sparked the interest of about a million visitors, who came to see the ruins, which include homes, a bridge, cemetery, and church. Then, in 2021, the lake was drained again. I wonder if this time was as much for the tourism factor, as it was for dam maintenance. Getting people to come to an area, where they will logically, spend money, is a great motivator, and from an educational aspect, being able to walk around in, and explore a 751-year-old village is pure gold. For many people, that is a once-in-a-lifetime event, and they will do whatever it takes to take part in such an event.

While I can fully understand their interest, I would like to know just how it is that this village from the year 1270 could possibly have held up in the first place. I would think that the water, and whatever organisms live in

the lake, would have caused the deterioration of the buildings in the village. Nevertheless, they seem to be holding up remarkably well. Maybe the builders back then used superior materials, or maybe the water somehow actually preserved the stones better that the air would have. Either way, I think this would have been quite a sight to see.

the lake, would have caused the deterioration of the buildings in the village. Nevertheless, they seem to be holding up remarkably well. Maybe the builders back then used superior materials, or maybe the water somehow actually preserved the stones better that the air would have. Either way, I think this would have been quite a sight to see.

If you visit the Colosseum in Rome these days, you will see a rough-looking shadow of its former glory. The Colosseum was built between 70 AD and 80 AD, under Emperors Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian, the Flavian Emperors. The original name of the Colosseum was the Amphitheatrum Flavium, or the Flavian Amphitheater. Viewed as a populist undertaking by Vespasian, the Colosseum was, at least in part, commissioned as a means to regain the favor of the people, who were restless and unhappy with the imperial institution after Nero’s reign. Planning began in 70 AD and construction in 72 AD. The site of the artificial lake that Nero had constructed as part of the Domus Aurea was chosen for the Colosseum.

If you visit the Colosseum in Rome these days, you will see a rough-looking shadow of its former glory. The Colosseum was built between 70 AD and 80 AD, under Emperors Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian, the Flavian Emperors. The original name of the Colosseum was the Amphitheatrum Flavium, or the Flavian Amphitheater. Viewed as a populist undertaking by Vespasian, the Colosseum was, at least in part, commissioned as a means to regain the favor of the people, who were restless and unhappy with the imperial institution after Nero’s reign. Planning began in 70 AD and construction in 72 AD. The site of the artificial lake that Nero had constructed as part of the Domus Aurea was chosen for the Colosseum.

Most of the labor for the construction of the building was provided by Jewish slaves, who had been taken as prisoners following the first Jewish-Roman war. The Colosseum was constructed of several materials, mainly travertine, limestone, and marble for decorations. They used tuff, volcanic rock, brick, and lime for links. Metals, mainly bronze, were used to bind the stones together. Travertine is a sedimentary limestone, that is found where rivers, springs, lakes used to exist. Beige in color, travertine typically forms in hot springs. The area around Rome is rich with travertine. It forms by the precipitation of calcium carbonate. The travertine that was used to build the Colosseum came from the town of Bagni di Tivoli, formerly Tibur. Travertine is the majority of the stone in the Colosseum, and most of what is left.

The Colosseum’s decorations were in mostly made of marble, but if you go to the Colosseum today, you will not find much of that marble. It has all but disappeared, because it has been reused in the construction of other buildings in Rome. I find that fact to be very strange, since the Colosseum would have been seen as an important center in Rome…or maybe that is just what it is today. The entrances of the cavea and the balustrades were decorated with marble pieces as well. The first 3 rows of seating were also made of marble, a luxury reserved for the most affluent social class. The columns on the outside had marble capitals, and some columns were also in marble.

Of course, metal was needed too. They had to be able to attach the marble to the structure. In the Colosseum, bronze was the primary metal used, but they also used iron. The metal, was heated and stretched into a bar, then curved into a U shape. Adapted to holes intentionally dug into the stones of the facade, these structures served as agraphs to help keep the Colosseum upright. The first fires got the better of these agraphs which were gradually recovered to be melted. Nowadays only the holes in the stones remain, vestiges of this originality in the construction.

The Colosseum was originally clad entirely in marble. When you visit or see the Colosseum these days you’ll notice how the stone exterior appears to be covered in pockmarks all across its surface. Some say that it was not the reusing of the marble in other buildings that brought the Colosseum to it’s current pockmarked state,

but rather that after the fall of Rome, the city was looted and pillaged by the Goths. They took all of the marble from the Colosseum, and stripped it down to its bare stone setting. Whatever really happened, or even if it was a combination of the two, the Colosseum that stands today looks like a war-torn, broken-down shadow of what it used to be, and yet the fact that it still stands, continues to draw many people from all over the world to visit it every year.

but rather that after the fall of Rome, the city was looted and pillaged by the Goths. They took all of the marble from the Colosseum, and stripped it down to its bare stone setting. Whatever really happened, or even if it was a combination of the two, the Colosseum that stands today looks like a war-torn, broken-down shadow of what it used to be, and yet the fact that it still stands, continues to draw many people from all over the world to visit it every year.

On this day, August 21, 1911, an amateur painter decided to paint a painting near Leonardo da Vinci’s famed Mona Lisa, only to find out that someone had walked into the Louvre that morning, taken the priceless painting off the wall, hidden it under his clothing, and walked out of the museum. The first thought is, of course, who would be so brazen, but my second thought is how could he have pulled that off? How much clothing would it take to simply “tuck” a 20 inch by 30 inch painting into his clothing. Nevertheless, earlier that day, Vincenzo Perugia had walked into the Louvre, removed the famed painting from the wall, hid it beneath his clothes, and escaped.

On this day, August 21, 1911, an amateur painter decided to paint a painting near Leonardo da Vinci’s famed Mona Lisa, only to find out that someone had walked into the Louvre that morning, taken the priceless painting off the wall, hidden it under his clothing, and walked out of the museum. The first thought is, of course, who would be so brazen, but my second thought is how could he have pulled that off? How much clothing would it take to simply “tuck” a 20 inch by 30 inch painting into his clothing. Nevertheless, earlier that day, Vincenzo Perugia had walked into the Louvre, removed the famed painting from the wall, hid it beneath his clothes, and escaped.

The theft, somehow carried out in complete secrecy, left the entire nation of France is shock. There were many theories as to what could have happened to the priceless painting. Strangely, professional thieves were not on the list of suspects, because they would have realized that it would be too dangerous to try to sell the world’s most famous painting. I suppose that a private art collector might have hired a professional to steal it for a secret collection, but that didn’t seem to be the case. One theory, or  rumor really, in Paris was that the Germans had stolen it to humiliate the French. I’m not sure that made any sense before either of the world wars, but I guess tensions between the nations could have been on the rise then.

rumor really, in Paris was that the Germans had stolen it to humiliate the French. I’m not sure that made any sense before either of the world wars, but I guess tensions between the nations could have been on the rise then.

For two years, investigators and detectives searched for the painting without finding any real leads. Then in November 1913, the thief mad his first move…the one that would eventually bring his doom. Italian art dealer Alfredo Geri received a letter from a man calling himself Leonardo. It indicated that the Mona Lisa was in Florence and would be returned for a hefty ransom. Why he waited two years to ask for a ransom is beyond me, other than the fear of getting caught. The meet was set to pay the ransom, and when Perugia attempted to receive the ransom, he was captured. The painting was recovered, unharmed.

In a way, you could say that this was an inside job. Perugia knew his way around, and knew areas where the  Louvre might be vulnerable. Perugia, a former employee of the Louvre, claimed that he had acted out of a patriotic duty to avenge Italy on behalf of Napoleon. That claim was disproven when prior robbery convictions and Perugia’s diary, with a list of art collectors, caused most people to believe that he had acted solely out of greed. Perugia served seven months of a one-year sentence and later served in the Italian army during the First World War. The Mona Lisa is back in the Louvre, where improved security measures are now in place to protect it. I guess that one good thing came of the theft…better security. Of course, that might have come with technological advances anyway.

Louvre might be vulnerable. Perugia, a former employee of the Louvre, claimed that he had acted out of a patriotic duty to avenge Italy on behalf of Napoleon. That claim was disproven when prior robbery convictions and Perugia’s diary, with a list of art collectors, caused most people to believe that he had acted solely out of greed. Perugia served seven months of a one-year sentence and later served in the Italian army during the First World War. The Mona Lisa is back in the Louvre, where improved security measures are now in place to protect it. I guess that one good thing came of the theft…better security. Of course, that might have come with technological advances anyway.

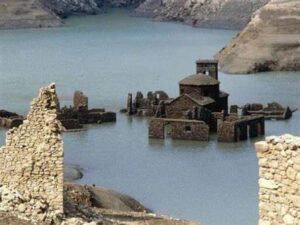

Curon Venosta was a village in northern Italy located in South Tyrol. Curon Venosta’s disappearance was not a mystery. The village suffered the same fate as numerous other towns over the years. The alpine village fell victim to the formation of a large man-made lake. The land was purchased and alpine village inundated shortly after World War II due to the construction of a dam. The officials had decided that they would join two smaller per-existing lakes into one large man-made lake.

Curon Venosta was a village in northern Italy located in South Tyrol. Curon Venosta’s disappearance was not a mystery. The village suffered the same fate as numerous other towns over the years. The alpine village fell victim to the formation of a large man-made lake. The land was purchased and alpine village inundated shortly after World War II due to the construction of a dam. The officials had decided that they would join two smaller per-existing lakes into one large man-made lake.

Originally, plans were made to make a smaller artificial lake dated back to the year 1920. Then, in July 1939 a new plan was introduced for a 75 foot deep lake, which would unify two natural lakes. The point of joining the lakes together was to create a hydroelectric dam. The creation of the dam started in April 1940, but due to World War II and local resistance, the project did not finish until July 1950.

The new larger lake had a capacity of 120 million cubic meters, making this artificial lake the largest lake in the province and its surface area of 2.5 square miles makes it also the largest lake above .6 miles in the Alps. During the project, 163 houses and nearly 1.300 acres of cultivated land was flooded. The structures were not torn down, they were just vacated and flooded. The entire village of Curon Venosta is still down there, filled with sand. All that remains of the old Curon Venosta is the tip of a bell tower, standing in the middle of the lake. As a consolation to the angry villagers, a new village was built at a higher elevation.

The 14th-century church steeple was left to stand as a historic memorial, and was restored in 2009 to repair cracks. During the winter months, the lake freezes over, and people enjoy a walk right up to the spire. A legend

says that during winter one can still hear church bells ring, but in reality the bells were removed from the tower on July 18, 1950. The village of Curon Venosta was once a village of hundreds of people, and then it was sacrificed in the name of energy. Now, 70 years later, the lake was drained to perform some repairs to the dam. The people living in the area talked about how strange it was to walk in the ruins of the village they hadn’t seen in seven decades. Of course the sight of the village was temporary, and when the work was done, the village disappeared once again.

says that during winter one can still hear church bells ring, but in reality the bells were removed from the tower on July 18, 1950. The village of Curon Venosta was once a village of hundreds of people, and then it was sacrificed in the name of energy. Now, 70 years later, the lake was drained to perform some repairs to the dam. The people living in the area talked about how strange it was to walk in the ruins of the village they hadn’t seen in seven decades. Of course the sight of the village was temporary, and when the work was done, the village disappeared once again.

Many people know that April 20th is Hitler’s birthday, not that most of us would celebrate that fact. Nevertheless, for the Allies in World War II, at least on April 20, 1945, that day meant something. Not because it was Hitler’s birthday…no, it was because the Allies had a plan. The Germans had been in control in much of Italy, and their advancement had to be stopped. As always, there were multiple campaigns planned on any given day in the war. One planned attack, called Operation Corncob, was to send Allied bombers into Italy to begin a three-day attack on the bridges over the rivers Adige and Brenta to cut off the German lines of possible retreat on the peninsula. They knew that Hitler would be otherwise occupied, it being his birthday and all…and so he was.

Many people know that April 20th is Hitler’s birthday, not that most of us would celebrate that fact. Nevertheless, for the Allies in World War II, at least on April 20, 1945, that day meant something. Not because it was Hitler’s birthday…no, it was because the Allies had a plan. The Germans had been in control in much of Italy, and their advancement had to be stopped. As always, there were multiple campaigns planned on any given day in the war. One planned attack, called Operation Corncob, was to send Allied bombers into Italy to begin a three-day attack on the bridges over the rivers Adige and Brenta to cut off the German lines of possible retreat on the peninsula. They knew that Hitler would be otherwise occupied, it being his birthday and all…and so he was.

Hitler was actually occupied for more reasons than just his birthday, as Soviet artillery had begun shelling Berlin at 11am on his 56th birthday. Preparations were being made to evacuate Hitler and his staff to Obersalzberg to make a final stand in the Bavarian mountains, but Hitler refused to leave his bunker. So, Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler left the bunker for the last time. Operation Herring had begun the day before, with American aircraft dropping Italian paratroopers over Northern Italy, and with Operation Corncob came the other half of the attack, which was to remove the bridges and thereby halt the expected retreat of the German forces. I doubt if Hitler knew anything about these attacks, I’m sure his mind was on his upcoming suicide, a death which some say didn’t really take place, and a fact which we will never know for sure.

The Allied attacks of April 1945 on the Italian front, were intended to end the Italian campaign and the war in Italy, and to decisively break through the German Gothic Line, the defensive line along the Apennines and the River Po plain to the Adriatic Sea and swiftly drive north to occupy Northern Italy and get to the Austrian and Yugoslav borders as quickly as possible. Unfortunately, German strongpoints, as well as bridge, road, levee and dike blasting, and any occasional determined resistance in the Po Valley plain slowed the planned sweep down. Allied planners decided that dropping paratroops into some key areas and locales south of the River Po might help wreak havoc in the German rear area, attack German communications, and vehicle columns, further disrupting the German retreat, and prevent German engineers from blowing up key structures before Allied spearheads could exploit them. Lieutenant General Sir Richard McCreery, commander of the Commonwealth 8th Army, had a number of Italian paratroopers at hand for the task.

Meanwhile, Adolf Hitler celebrated his 56th birthday with a traditional parade and full celebration, while a

Gestapo reign of terror took the lives by hanging of 20 Russian prisoners of war and 20 Jewish children, at least nine of which were under the age of 12. All of the victims had been taken from Auschwitz to Neuengamme, the place of execution, for the purpose of medical experimentation. Hitler and his Third Reich didn’t fully understand it then, but they were finished, and the end was coming quickly.

Gestapo reign of terror took the lives by hanging of 20 Russian prisoners of war and 20 Jewish children, at least nine of which were under the age of 12. All of the victims had been taken from Auschwitz to Neuengamme, the place of execution, for the purpose of medical experimentation. Hitler and his Third Reich didn’t fully understand it then, but they were finished, and the end was coming quickly.