infantry

As I have researched the infantry soldiers of World War II, my thought was that I was really thankful that my dad, Allen Spencer was not one of those men on the ground during the fighting. I felt bad for those men who were on the ground, fighting from the foxholes. I still do, because they were in constant danger. Bombs fall from the sky, and bullets fly from across the battlefield. If those things didn’t kill a soldier, the freezing cold, trench foot, or dysentery from the horribly unsanitary conditions could. It seemed that my dad’s situation was by far safer, but now, I’m not so sure that’s true.

As I have researched the infantry soldiers of World War II, my thought was that I was really thankful that my dad, Allen Spencer was not one of those men on the ground during the fighting. I felt bad for those men who were on the ground, fighting from the foxholes. I still do, because they were in constant danger. Bombs fall from the sky, and bullets fly from across the battlefield. If those things didn’t kill a soldier, the freezing cold, trench foot, or dysentery from the horribly unsanitary conditions could. It seemed that my dad’s situation was by far safer, but now, I’m not so sure that’s true.

The book I had been listening to, that took in World War II from D-Day to The Battle of the Bulge, talked mostly about the ground war, but then at the end, the reader said something that really struck me. It was about the look that crossed the face of a bomber crew’s faces before certain missions…those that would inevitably find the plane flying through flak. The look was one of fear. I knew flak was dangerous, but somehow I didn’t really connect flak with bringing down a plane, or seriously injuring its occupants. Nevertheless, it is quite dangerous for them.

As I researched the dangers of flak, a shocking revelation made itself known. I had written a story about the life expectancy of the ball turret gunner. My findings were that that life expectancy was about 12 seconds. That may be true when one is talking about the prospect of being shot, but when it comes to flak, that cannot be said. Apparently, where flak is concerned, the best place to be is in the plexiglass structure of the ball turret. Plexiglass holds up better against flak than other areas of the plane, so the ball turret gunner is much more protected…at least from flak. The same cannot be said for the bullets flying through the area. I was thankful that my dad was not a ball turret gunner, and that he only filled in as a waist gunner periodically. The waist gunners were in the open, where protection from bullets, and from flak was minimal…at best, non-existent at worst. I can’t imagine how those memories must have affected my dad, but in the book I listened to, the main reason many of the men didn’t want to talk about their experiences in World War II, or any war, was because talking about it brought those memories flooding in again.

After researching flak, and how it works, I can see why the men would get a look of fear on their faces as they prepared to go through areas anti-aircraft weapons shooting flak into the air. Some men said that they could see the red hot glow in the center of the flak, if it was very close. That tells me that it was like a small explosive devise. No wonder it could bring so much damage to a plane. I had known that flak could put holes in the fuselage, but somehow I hadn’t tied that with bringing down a plane. I surmise that it was the B-17

bomber top turret gunner’s daughter in me that wouldn’t allow me to place that danger around my dad. I didn’t want to think about the dangers of his every mission in World War II. My mind seems to have placed his plane in a bubble or a force field, so that no danger could come near him. I think every veteran wonders why they were spared, when others didn’t make it back home. I don’t think anyone can answer that question. As a Christian, I have to credit God for bringing my future dad home.

bomber top turret gunner’s daughter in me that wouldn’t allow me to place that danger around my dad. I didn’t want to think about the dangers of his every mission in World War II. My mind seems to have placed his plane in a bubble or a force field, so that no danger could come near him. I think every veteran wonders why they were spared, when others didn’t make it back home. I don’t think anyone can answer that question. As a Christian, I have to credit God for bringing my future dad home.

After World War II, many of the veterans were hesitant to talk about their experiences. My dad, Allen Spencer was one of those men. We were never exactly sure why he didn’t talk about it, but thought that he didn’t want to brag. I don’t really think that was it at all.

After World War II, many of the veterans were hesitant to talk about their experiences. My dad, Allen Spencer was one of those men. We were never exactly sure why he didn’t talk about it, but thought that he didn’t want to brag. I don’t really think that was it at all.

While listening to an audiobook called Citizen Soldiers, which covers the D-Day battle and the Battle of the Bulge, it hit me…even before the author said it. The reason soldiers didn’t talk much about war was a deliberate effort to forget. Unfortunately for most of her them, forgetting was impossible. Their minds were filled with haunted memories. The book mostly covers the thoughts of the infantry, but touches on the air war too.

After listening to the author’s account of the battle, I don’t think I could ever forget either, and I wasn’t there. Memories of the 19 year old farm boy away from home for the first time, and not really trained for combat. When the shooting started, he stood up to fire. Other soldiers told him to get down, by it was too late. His first battle had become his last, as an enemy bullet pierced his forehead. The soldiers who witnessed it, felt sick to

their stomachs. It was a time when a seasoned veteran was just 22 years old…and he had been made an office when his commanding officer was killed. There weren’t very many of the older men left…and by older I mean 30.

their stomachs. It was a time when a seasoned veteran was just 22 years old…and he had been made an office when his commanding officer was killed. There weren’t very many of the older men left…and by older I mean 30.

There were memories of a young prisoner of war, packed into a train to the POW camps was singing in his beautiful tenor voice, all the Christmas music he could think of to help raise moral. It was working, but suddenly the trains were under attack. The prisoners couldn’t get out, and the guards had run away. Finally a skinny boy was able to get out through a tiny window. He opened the door to his car and the men moved to free the other prisoners. There was really nowhere to go, but they escaped the attack. Then, the guards came back and loaded them back on the train. When someone asked the tenor to sing some more, they were told that he hadn’t made it back. His sweet voice was forever silenced. The men on the train were silent too…sick at heart.

The fighters in the plane’s overhead knew that it was kill or be killed, but whenever a plane went down, enemy

or one of theirs, they counted the parachutes, hoping the men got out alive. For them non the planes dropping bombs, they knew that someone below went to work that day, having no idea tat they would not be returning home again. They had been simple factory workers, just doing what they were told. And what of the missed targets that landed bombs on schools and other civilian locations. The men in the planes above had to live with that. They had done their duty, but it certainly didn’t feel good.

or one of theirs, they counted the parachutes, hoping the men got out alive. For them non the planes dropping bombs, they knew that someone below went to work that day, having no idea tat they would not be returning home again. They had been simple factory workers, just doing what they were told. And what of the missed targets that landed bombs on schools and other civilian locations. The men in the planes above had to live with that. They had done their duty, but it certainly didn’t feel good.

Every family has it strange characters. For mine it would have to be my great great grandfather, David Martin Pattan. Some might have called him eccentric, or even crazy , but no one really knows exactly why he did the things he did…or, as is the case for some parts of his life, why he did the things he did…over and again.

Every family has it strange characters. For mine it would have to be my great great grandfather, David Martin Pattan. Some might have called him eccentric, or even crazy , but no one really knows exactly why he did the things he did…or, as is the case for some parts of his life, why he did the things he did…over and again.

After David’s parents died on Ohio, which is where David was born in about 1828, he moved to Illinois and settled in Knox County near Gibson. He met and married my great great grandmother, Elizabeth Ellen Shuck on December 25, 1856 in Knoxville, Illinois. Together they had six sons and four daughters. As I look at the marriage certificate, I looks like his last name was spelled Patten and Elizabeth’s was spelled Shuck. We have always spelled his Pattan and hers Schuck.

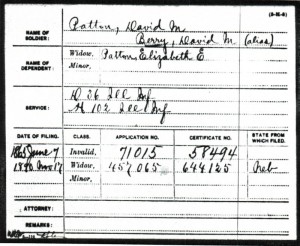

During the Civil War, he enlisted in Company H 102nd Illinois Volunteer Infantry on August 8, 1862, a little less than a year after his third son, Joseph was born. He was discharged on October 1, 1863, just 3 days before Joseph’s third birthday. At his discharge his had a disease of the larynx and bronchia that caused him not to be able to speak louder that a whisper for two months. He then enlisted in Company D36 Illinois Volunteer Infantry on September 27, 1864. It is unknown if he just forgot that he had already served, or if he just felt that his services were needed again. He was shot in the right arm, just above the elbow, in the Battle of Lookout Mountain in Tennessee on November 29, 1864. He spent the next five weeks in a hospital in Cincinnati, Ohio. Upon his discharge, he was sent back to his unit. He was discharged on May 20, 1865 with 1/2 disability.

After David’s discharges from his times in the infantry, he and Elizabeth had their remaining seven children. At some point after the birth of their twins in 1876, David went to town and didn’t come back. He was gone for seventeen years. Then, one day in town, David’s son George, my grandfather, saw him in town. The sheriff was about to arrest him, when George offered to take him home. I guess he must have been drinking or causing some other such mischief that didn’t necessarily warrant jail time. Once home, they found out that he had been married to another woman and they had a son and a daughter, both of whom were named the same names as a son and daughter with Elizabeth. This leads me to wonder if something had happened seventeen years earlier that caused him not to remember the first marriage. That family died in a flash flood, so maybe that was why he was back. I have heard that he was married one more time…again without the benefit of a divorce, and when the third wife tried to collect his pension, she was denied because they weren’t legally married. No children were born to that union.

I don’t know if my great great grandfather was just a man who liked to marry different women, or if there was truly something mentally wrong with him. I have found out that his name was spelled every way you can possibly spell Pattan…Patton, Patten…and that for a time at least, he went by the alias, David Martin Berry. Berry was his mother’s maiden name, so I  guess that worked. I have to wonder if he used the other names so that he could keep the wives straight…again, if he mentally knew that he was married. The research on his marriages is complicated due to these differences in names, but I have to wonder if the third wife, at least, went by berry, because that name is listed on the pension request, probably to avoid paying out twice. Whatever the reasons were for his double military service, and his three marriages, my great great grandmother took him back, and in the end cared for him until his dying day. They are buried together in Little York Cemetery in Warren Illinois.

guess that worked. I have to wonder if he used the other names so that he could keep the wives straight…again, if he mentally knew that he was married. The research on his marriages is complicated due to these differences in names, but I have to wonder if the third wife, at least, went by berry, because that name is listed on the pension request, probably to avoid paying out twice. Whatever the reasons were for his double military service, and his three marriages, my great great grandmother took him back, and in the end cared for him until his dying day. They are buried together in Little York Cemetery in Warren Illinois.