holocaust

Adolf Hitler was quite possibly one of the most insane people of all time, but apparently much of the hateful things he did were actually done under the influence of Opioids and Meth. Does that excuse his behavior? Absolutely not. Even on opioids and meth, there was a monster that existed deep on the inside of that man. There was a deep-seated hatred that made him do the things he did. The opioids and meth merely gave him the ability to continue on in his hatred, and it wasn’t just Hitler that was regularly using these drugs to carry out their hateful tasks. It is common knowledge that many of the soldiers under Hitler either didn’t know the truth of everything that was going on, and still others were afraid to argue the point for fear of their own death. For many of those people, the use of drugs was the only escape from the horrors of what they had to do.

Adolf Hitler was quite possibly one of the most insane people of all time, but apparently much of the hateful things he did were actually done under the influence of Opioids and Meth. Does that excuse his behavior? Absolutely not. Even on opioids and meth, there was a monster that existed deep on the inside of that man. There was a deep-seated hatred that made him do the things he did. The opioids and meth merely gave him the ability to continue on in his hatred, and it wasn’t just Hitler that was regularly using these drugs to carry out their hateful tasks. It is common knowledge that many of the soldiers under Hitler either didn’t know the truth of everything that was going on, and still others were afraid to argue the point for fear of their own death. For many of those people, the use of drugs was the only escape from the horrors of what they had to do.

Still, there were many people who were truly evil, and it’s quite likely that those people simply used the drugs to “enhance” the horrific experience, and by enhance, I mean they very much enjoyed the killing and in their twisted minds, the use of the drugs made it more “pleasurable” to do the things they did. The drugs also kept the Nazis awake for many more hours than they might otherwise have been able to endure. The Nazi call was “Germany awake!” The orders were constantly barked out, and they meant it more than most people even knew. As Nazi Germany battled its way through World War II, the country relied on a little secret to stay “energetic.” It was known as Pervitin. It was used by the soldiers to avoid sleep and to numb the terror of battle. Housewives later popped Pervitin so they could “finish all their chores and lose weight” too. It turns out, however, that it was just pure methamphetamine. And Adolf Hitler himself relied on even stronger remedies, taking a drug called Eukodal, effectively a cocktail of oxycodone and cocaine, to treat various “ailments.”

By 1941, a top German health minister wrote a letter fretting that the entire nation was “becoming addicted to drugs” but it made little difference to Hitler or anyone else. Indeed, there remains a “trove of weird historical facts about drug use in Nazi Germany” that would totally astound even World War II buffs. We already knew that Hitler was evil and crazy, but now we know more about how he was able to keep going with all his hate.

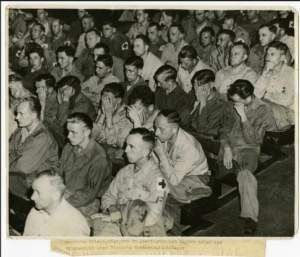

For some or most of the soldiers, it was likely a way to control what they did. I’m sure a ‘mutiny” would have been catastrophic for Hitler’s master plan against the Jews. When some of those soldiers saw the atrocities that occurred, they actually wept. Many of them had no idea what was really going on…and I’m sure that was exactly what Hitler wanted.

For some or most of the soldiers, it was likely a way to control what they did. I’m sure a ‘mutiny” would have been catastrophic for Hitler’s master plan against the Jews. When some of those soldiers saw the atrocities that occurred, they actually wept. Many of them had no idea what was really going on…and I’m sure that was exactly what Hitler wanted.

Anytime a government is going to pull off a big change, there must be meetings…planning meetings, if you will. The Third Reich, under Adolf Hitler had long wanted to literally remove the Jewish people from the face of the earth. They began making plans for what they called “The Final Solution to the Jewish Question” and later called the Wannsee Conference to ensure the co-operation of administrative leaders of various government departments in its implementation.

Anytime a government is going to pull off a big change, there must be meetings…planning meetings, if you will. The Third Reich, under Adolf Hitler had long wanted to literally remove the Jewish people from the face of the earth. They began making plans for what they called “The Final Solution to the Jewish Question” and later called the Wannsee Conference to ensure the co-operation of administrative leaders of various government departments in its implementation.

The Wannsee Conference was called by the director of the Reich Security Main Office SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich and included senior government officials of Nazi Germany and Schutzstaffel (SS) leaders. The conference was held in the Berlin suburb of Wannsee on January 20, 1942. The plan of the “Final Solution” was to deport most of the Jews of German-occupied Europe to occupied Poland, where they would be murdered. Hitler was obsessed with what he considered purifying the world. He wanted to build an Aryan race, which is “white non-Jewish people, especially those of northern European origin or descent typically having blond hair and blue eyes and regarded as a supposedly superior racial group.”

In the course of the meeting, Heydrich outlined how European Jews would be rounded up and sent to extermination camps in the General Government (the occupied part of Poland), where they would be killed. Of course, the meetings were merely a formality. The decisions had been made and they were not asking for the support of the attendees, but rather they were simply telling them what they would be doing…if they wanted to live, that is.

Hitler began his discrimination against Jews began immediately after the Nazi seizure of power on January 30, 1933. At first, he employed violence and economic pressure to encourage Jews to voluntarily leave the country. Sadly, the Jews thought that with compliance, they would be ok, but Hitler was determined to remove them from Germany…one way or the other. Then, after the invasion of Poland in September 1939, Hitler stepped up his plan for the extermination of European Jewry and began the killings.

The killings continued and accelerated after the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. On July 31, 1941, Hermann Göring gave written authorization to Heydrich to “prepare and submit a plan for a ‘total solution of the Jewish question’ in territories under German control and to coordinate the participation of all involved government organizations.” At the Wannsee Conference, Heydrich emphasized that “once the deportation  process was complete, the fate of the deportees would become an internal matter under the purview of the SS. A secondary goal was to arrive at a definition of who was Jewish.” Basically, this meant that the Jewish deportees would simply “disappear” into thin air and never be heard from again. Just one copy of the “Protocol” with circulated minutes of the meeting survived the war. It was found by Robert Kempner in March 1947 among files that had been seized from the German Foreign Office. That copy was used as evidence in the subsequent Nuremberg trials. Like many other Holocaust sites, The Wannsee House is now a Holocaust memorial.

process was complete, the fate of the deportees would become an internal matter under the purview of the SS. A secondary goal was to arrive at a definition of who was Jewish.” Basically, this meant that the Jewish deportees would simply “disappear” into thin air and never be heard from again. Just one copy of the “Protocol” with circulated minutes of the meeting survived the war. It was found by Robert Kempner in March 1947 among files that had been seized from the German Foreign Office. That copy was used as evidence in the subsequent Nuremberg trials. Like many other Holocaust sites, The Wannsee House is now a Holocaust memorial.

After years of being oppressed, starved, beaten, murdered, and used for experimentation, the Jewish people decided that it was their right to avenge their dead. The Nuremburg Trials were supposed to do all that, but so many of the Nazis had fled the country to escape the sentences they deserved, and once out of the country, it was almost impossible to get them back to face those sentences. In the late 1940s, under Juan Domingo Peron’s leadership (October 17, 1945 to July 1, 1974), the government secretly allowed entry of a number of war criminals fleeing Europe after Nazi Germany’s collapse, as part of the infamous ratlines. The number of Nazi fugitives that fled to Argentina surpassed 300, and included notorious war criminals such as Erich Priebke, Martin Bormann, Joseph Mengele, Eduard Roschmann, Josef Schwammberger, Walter Kutschmann, Otto Skorzeny and Holocaust administrator Adolf Eichmann, among others. In May 1960, Eichmann was kidnapped in Argentina by the Israeli Mossad and brought to trial in Israel. He was executed in 1962. At the time, Argentina condemned the Israeli government for abducting Eichmann, leading to a diplomatic spat between the nations.

After years of being oppressed, starved, beaten, murdered, and used for experimentation, the Jewish people decided that it was their right to avenge their dead. The Nuremburg Trials were supposed to do all that, but so many of the Nazis had fled the country to escape the sentences they deserved, and once out of the country, it was almost impossible to get them back to face those sentences. In the late 1940s, under Juan Domingo Peron’s leadership (October 17, 1945 to July 1, 1974), the government secretly allowed entry of a number of war criminals fleeing Europe after Nazi Germany’s collapse, as part of the infamous ratlines. The number of Nazi fugitives that fled to Argentina surpassed 300, and included notorious war criminals such as Erich Priebke, Martin Bormann, Joseph Mengele, Eduard Roschmann, Josef Schwammberger, Walter Kutschmann, Otto Skorzeny and Holocaust administrator Adolf Eichmann, among others. In May 1960, Eichmann was kidnapped in Argentina by the Israeli Mossad and brought to trial in Israel. He was executed in 1962. At the time, Argentina condemned the Israeli government for abducting Eichmann, leading to a diplomatic spat between the nations.

There was a financial incentive for Argentina to accept these war criminals, and they needed to provide a safe haven for them. Wealthy Germans and Argentine businessmen of German descent were willing to pay the way for escaping Nazis. The initial plan of the fleeing Nazis was to regroup, lay low for a while, and then come back with a vengeance. The Holocaust years had been very profitable for the Nazis. Nazi leaders had plundered untold millions from the Jews they murdered and some of that money accompanied them to Argentina…meaning the Argentine economy was helped by the war criminals…another incentive to help them hide out.

Some of the smarter Nazi officers and collaborators saw the writing on the wall as early as 1943 and began hiding gold, money, valuables, paintings, and more. They often moved their plunder to Switzerland. Ante Pavelic and his cabal of close advisors had several chests full of gold, jewelry, and art they had stolen from their Jewish and Serbian victims. These riches eased their passage to Argentina considerably. Disappearing, even in 1945 was not an easy matter, but if one had money, it was far more possible. The war criminals even paid off British officers to let them through Allied lines…a treasonous act for which those British officers should have  also been prosecuted and hung. Sometimes the corruption in government and military entities, even those who are supposed to be on the side of good, is absolutely astounding.

also been prosecuted and hung. Sometimes the corruption in government and military entities, even those who are supposed to be on the side of good, is absolutely astounding.

After the World War II, and the release of the surviving Jews, the Nuremburg Trials convicted these evil monsters, but many of them were gone before their sentence could be carried out. Enter the Nokmim, a group of Jewish men, also referred to as The Avengers or the Jewish Avengers. These men were a Jewish partisan militia, formed by Abba Kovner and his lieutenants Vitka Kempner and Rozka Korczak from the surviving remnants of the United Partisan Organization (Fareynikte Partizaner Organizatsye), which operated in Lithuania under Soviet command. Elements of the Nokmim collaborated with veterans of the Jewish brigade in British Palestine to form a new organization called Nakam, a group of assassins that targeted Nazi war criminals with the aim of avenging the Holocaust. The name comes from the phrase (Dam Yehudi Nakam – “Jewish Blood Will Be Avenged”) (the acronym DIN means “judgement”).

The Nakam (“vengeance”) Group was the most extremist group. They numbered around 60 Jews who were former Partisans, as well as other Jews who survived the Holocaust. This group was not about to let these men get away with all the atrocities they put their Jewish captives through, and then just walk away without punishment…not if they could help it. The group arrived in Germany after the war in order to conduct more complicated and fatal vengeance operations. Their ultimate purpose was to carry out an operation that would cause a broad international response…a warning, if you will, to anyone who might consider trying to harm Jews again, as the Nazis had. They needed to show the world that they would never be treated in such a way again. They would fight back…every time. Notables among the Hanakam group were Abba Kovner, Yitzhak Avidav, and Bezalel Michaeli. The group attempted a couple of mass poisonings, the first of the water supplies of Munich, Berlin, Weimar, Nuremberg and Hamburg, which failed when the poison had to be thrown overboard on a ship when Kovner was discovered to be carrying forges documents. The other attempt was with 3,000 loaves of bread painted with diluted arsenic, headed for 15,000 German POWs from the Langwasser internment camp near Nuremberg. The camp was under US authority. On April 23, 1946, it was reported that 2,283 German prisoners of war had fallen ill from poisoning, with 207 hospitalized and seriously ill. According to Harmatz, 300 to 400 Germans died. He said this “was nothing compared with what we really wanted to do.” A 2016 report by the Associated Press countered that the operation ultimately caused no known deaths, despite documents obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request to the National Archives and Records Administration  stating the arsenic found in the bakery was enough to kill approximately 60,000 persons. Apparently, the arsenic was spread too thin to be lethal.

stating the arsenic found in the bakery was enough to kill approximately 60,000 persons. Apparently, the arsenic was spread too thin to be lethal.

It’s hard to say just how much information is correct and how much is incorrect. I suppose it depends on who is reporting, and how accurately they want to report what they have. Propaganda in any war runs rampant, so we will likely never know. Records can and do go missing, especially when someone wants to disprove their enemies. Whether so many people died by poisoning or not, the Nokmim and the spin-off Nakam brought vengeance on many of the Nazis who would have escaped justice without them.

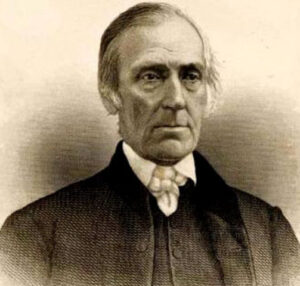

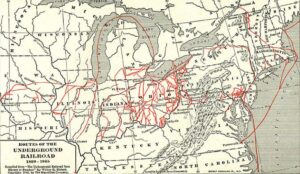

In any kind of slavery situation, there are always people who are willing to help those who are being held against their will. Just like during the Holocaust, when the slaves were in trouble, people came to their rescue by forming the Underground Railroad. One hero of the Underground Railroad was Levi Coffin. In the winter of 1826-1827, fugitives began to come show up at the Coffin house. It started out as a well-kept secret and just a few slaves came, but the numbers increased as it became more widely known on different routes. These slaves were running away from bondage, beatings, and limitless working hours. Their lives were little better than death, and they knew they had to escape or die.

In any kind of slavery situation, there are always people who are willing to help those who are being held against their will. Just like during the Holocaust, when the slaves were in trouble, people came to their rescue by forming the Underground Railroad. One hero of the Underground Railroad was Levi Coffin. In the winter of 1826-1827, fugitives began to come show up at the Coffin house. It started out as a well-kept secret and just a few slaves came, but the numbers increased as it became more widely known on different routes. These slaves were running away from bondage, beatings, and limitless working hours. Their lives were little better than death, and they knew they had to escape or die.

When they arrived at the Coffin house, they were welcomed in and given shelter, they would usually sleep during the day, and then they were quickly forwarded safely on their journey. Neighbors who had been too fearful of the penalty of the law to help at first, saw how well the Underground Railroad was being run and soon they felt encouraged to help. A big part of the change of attitude came from the fearless manner in which Levi Coffin acted and the success his efforts produced. The neighbors began to contribute clothing the fugitives and aid in forwarding them on their way. They were still too afraid to shelter them under their own roof, so that part of the work fell to the Coffin household. There were the “content to watch” people, who obviously wanted to see the work go on…as long as someone else took the risk. And of course, there were those who told Levin Coffin he was wasting his time. They tried to discourage him and dissuade him from running such risks, telling him that they were greatly concerned for my safety and monetary interests. They tried to convince him that continuing this risky business could damage his business and possibly even ruin him. The told him he could be  endangering himself and his family too. I suppose it could have, because there are always those who sympathized with the slave-owners, but Levi Coffin could not stand to see the horrible treatment the slaves endured. He had to do something, no matter what it cost him, just like those who helped the Jews during the Holocaust.

endangering himself and his family too. I suppose it could have, because there are always those who sympathized with the slave-owners, but Levi Coffin could not stand to see the horrible treatment the slaves endured. He had to do something, no matter what it cost him, just like those who helped the Jews during the Holocaust.

Levi listened to these “counselors” and then told them that he “felt no condemnation for anything that I had ever done for the fugitive slaves. If, by doing my duty and endeavoring to fulfill the injunctions of the Bible, I injured my business, then let my business go. As to my safety, my life was in the hands of my Divine Master, and I felt that I had his approval. I had no fear of the danger that seemed to threaten my life or my business. If I was faithful to duty and honest and industrious, I felt that I would be preserved and that I could make enough to support my family.”

Even some of those people who were opposed to slavery, felt it was very wrong to harbor fugitive slaves. They figured that the slaves must be guilty of some crime, such as possibly killing their masters or committed some other crime in their escape attempts…making those who helped them an accomplice to the “crime” they were supposedly guilt of. Oh, they had every imaginable objection, and figured it was, at the very least, their duty to make their thoughts known. Once they had voiced their objections, their conscience was clear, and if Levi met with a tragic end, they could at least say, “I told him!!” Levi, in return asked one such “neighbor’s keeper” neighbor, if he thought the Good Samaritan stopped to inquire whether the man who fell among thieves was guilty of any crime before he attempted to help him? He said, “I asked him if he were to see a stranger who had fallen into the ditch would he not help him out until satisfied that he had committed no atrocious deed?” I suppose it was a “crime” to escape their masters, but then some laws should not be laws, and slavery certainly falls into that category. Levi Coffin had to follow his spirit and do what he felt God would expect of him, and in  the end, he saved many lives.

the end, he saved many lives.

Many of Levi’s pro-slavery customers left him for a time, and sales were down. For while his business struggled, but Levi knew that he was doing God’s will, and so God would take care of him and his business. Before long, new customers replaced those who had left him. New settlements were rapidly forming to the north and Levi’s own was filling up with emigrants from North Carolina and other States. His trade increased and his business grew. He says of this time in his life, “I was blessed in all my efforts and succeeded beyond my expectations.”

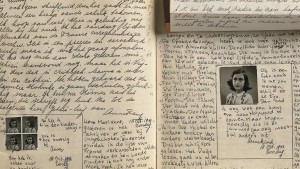

On June 12, 1942, Anne Frank, was a young Jewish girl living in Amsterdam. It was her thirteenth birthday, and as a gift, she was given a diary. Diaries have long been a big deal for girls. I know very few of those in my generation who didn’t have one. Most of those who received them, did little with them. I know that my diary (which I still have, by the way) contains mostly the gibberish of a young girl…mostly bored with the idea of journaling the meager events of my life…or at least that is how I saw them at the time. Looking back, I wish I had maybe taken the whole journaling/diary thing more seriously, because my life, while not as intense as that of Anne Frank, did have meaning, and those events that might have been considered important to my children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren have been, for the most part, lost to the forgetfulness of childhood.

On June 12, 1942, Anne Frank, was a young Jewish girl living in Amsterdam. It was her thirteenth birthday, and as a gift, she was given a diary. Diaries have long been a big deal for girls. I know very few of those in my generation who didn’t have one. Most of those who received them, did little with them. I know that my diary (which I still have, by the way) contains mostly the gibberish of a young girl…mostly bored with the idea of journaling the meager events of my life…or at least that is how I saw them at the time. Looking back, I wish I had maybe taken the whole journaling/diary thing more seriously, because my life, while not as intense as that of Anne Frank, did have meaning, and those events that might have been considered important to my children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren have been, for the most part, lost to the forgetfulness of childhood.

Many of us have heard of, read about, or seen the movie about the events of Anne Frank’s short life. One short month after receiving her diary, Anne and her family went into hiding from the Nazis in rooms behind her father’s office. Anne’s sister, Margot, received a call-up notice around 3pm on July 5, 1942. The Frank family had planned to go into hiding on July 16, 1942, but they decided to leave immediately so that Margot would not have to be deported to a “work camp.” The family left a false trail indicating that they had gone into hiding in Switzerland. According to Anne’s diary, Margot kept a diary of her own, but no trace of Margot’s diary has ever been found. This and her time in the hands of the Nazis was the main period of her diary, because as we know, Anne did not survive the Holocaust into which she and her family had been dragged. The hiding place was not discovered immediately, of course, and for the next two years, the Franks and four other families were hidden, fed, and cared for by Gentile friends. They lived in an annex, whose entrance was hidden behind a moveable bookcase. Following a tip in 1944, the families were discovered by the Gestapo. The Franks were taken to Auschwitz, where Anne’s mother died. Friends in Amsterdam searched the rooms and found Anne’s diary hidden away. They had hoped to save any personal items, so they could be returned to the family, should any of them survive.

Anne and her sister were sent to another camp, Bergen-Belsen, where Anne died a month before the war ended. Anne’s father survived Auschwitz, and after much soul searching, he published Anne’s diary in 1947 as “The Diary of a Young Girl.” The book has been translated into more than 60 languages. Had it not been for World War II, the Holocaust, and Anne’s tragic death from Typhus in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in February 1945, the diary would have most likely have been published, or even written in the way that it was.

The reality is that most diaries aren’t immensely interesting. Most are written by young girls with drama queen emotions, who are bored with their lives, because they are certain that nothing cool happens. Anne’s diary was interesting, because she wasn’t sure how long her life would be, and she wanted to know everything…before it was too late.

The reality is that most diaries aren’t immensely interesting. Most are written by young girls with drama queen emotions, who are bored with their lives, because they are certain that nothing cool happens. Anne’s diary was interesting, because she wasn’t sure how long her life would be, and she wanted to know everything…before it was too late.

Not everyone was surprised at the coming murders of the Jews during the Holocaust. People hoped that the rumors were wrong, and that maybe they war would end before things got that bad, but most knew that if something wasn’t done, things were going to get ugly at some point. In the end, the non-Jews were forced to make a decision…take a stand, or stand by and watch millions of people die.

Not everyone was surprised at the coming murders of the Jews during the Holocaust. People hoped that the rumors were wrong, and that maybe they war would end before things got that bad, but most knew that if something wasn’t done, things were going to get ugly at some point. In the end, the non-Jews were forced to make a decision…take a stand, or stand by and watch millions of people die.

A Danish ambulance driver in Copenhagen, Denmark huddled over a local phone book, circling Jewish names. He had heard that all of Denmark’s Jews were going to be deported, and he knew this was his “moment of truth.” He knew he had to warn every one of these people, before it was too late. He wasn’t alone. Hundreds of everyday Danes sprang into action in late September 1943. They all had one collective goal in mind…to help their Jewish friends and neighbors escape the horrors they knew were coming.

The plan was amazing. Hundreds of people helped Jewish people sneak out of Copenhagen and other towns. They quickly headed toward Danish shores and into the crowded holds of tiny fishing boats. Denmark was about to pull off a spectacular feat…the rescue of the vast majority of its Jewish population. Within a few hours of learning that the Nazis intended to wipe out Denmark’s Jews, nearly all of the Danish Jews had gone into hiding. Within a few days, most of them had escaped Denmark to neutral Sweden. In the end, over 90% of the Danish Jews were snatched out of the hands of Adolf Hitler and his goons, and it was all thanks to ordinary Danes, most of whom refused to accept credit for their ations. I call it a miracle, and the participants…angels!!

The German forces invaded Denmark in April 1940. The Danish government, rather than suffer an inevitable defeat by fighting back, didn’t resist the Nazi hoard. Instead, the Danish government negotiated with the Germans to insulate Denmark from the occupation. In the negotiations, the Nazis promised to be lenient with the country, respecting its rule and neutrality…like they would ever keep that promise. By 1943, tensions had reached a breaking point. Workers began to sabotage the war effort and the Danish resistance ramped up their efforts to fight the Nazis. In response, the Nazis told the Danish government to institute a harsh curfew, forbid public assemblies, and punish saboteurs with death. The Danish government refused, so the Nazis dissolved the government and established martial law.

The Nazis had always been a forbidding presence in Denmark, but now they began really making their presence known. Like everywhere else, the Danish Jews were to be their first targets. The Holocaust was spreading across occupied Europe, and without the protection of the Danish government, which had done its best to shield Jews from the Nazis after realizing that the Nazi promises were worthless, Denmark’s Jewish population was in danger. In late September 1943, the Nazis got word from Berlin that it was time to rid Denmark of its Jews. As was typical for the Nazis, they planned the raid to coincide with a significant Jewish holiday…in this case, Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. Marcus Melchior, a rabbi, got word of the coming raid, and in Copenhagen’s main synagogue, he interrupted services. Melchior said, “We have no time now to continue prayers. We have news that this coming Friday night, the night between the first and second of October, the Gestapo will come and arrest all Danish Jews.” Melchior told the congregation that the Nazis had the names and addresses of every Jew in Denmark, and urged them to flee or hide.

Denmark’s panicked Jewish population sprang into action, but against all odds, so did its Gentiles. Hundreds of people spontaneously began to tell Jews about the upcoming action and help them go into hiding. It was, in the words of historian Leni Yahil, “a living wall raised by the Danish people in the course of one night.” It was amazing, and it can only be classified as a miracle. The Gentile people of Denmark were taking their lives into their own hands too, but they did not care, nor did they consider the cost. All they saw was the horrific injustice of the Nazi plan, and they could not abide by it.

No pre-existing plan had been put in place by the Danish people, but the Jewish people needed their help and nearby Sweden offered an obvious haven to those who were about to be deported. Sweden was still neutral and unoccupied by the Nazis, and they were a fierce ally. It was also close. Some areas of Denmark were just over three miles away from the Swedish coast. Once across, the Jews could apply for asylum there. The Danish culture has long been seafaring, in fact since Viking times. That said, there were plenty of fishing boats and other vessels to spirit Jews toward Sweden. But Danish fishermen were worried about losing their livelihoods and being punished by the Nazis if they were caught. So, rather than put their countrymen in peril, the resistance groups that swiftly formed to help the Jews managed to negotiate standard fees for Jewish passengers, then recruit volunteers to raise the money for passage. That way the fishermen got paid for their risk. The average price of passage to Sweden cost up to a third of a worker’s annual salary.

As often happens, there were fishermen who took advantage of the situation, but more who refused pay, acting without regard to personal gain. Boats were used for some 7,000 Danish Jews who fled to safety in neighboring Sweden. Passage was a terrifying ordeal. Jews gathered in fishing towns, hid on small boats, usually 10 to 15 at a time, giving their children sleeping pills and sedatives to keep them from crying, and struggled to maintain control during the hour-long crossing. Some boats, like the Gerda III, were boarded by Gestapo patrols. Gas came from strange sources. Careful rationing by groups like the “Elsinore Sewing Club,” a resistance unit, helped a few hundred Jews make the crossing.

There were failures sadly. In Gilleleje, a small fishing town, hundreds of refugees were being cared for by locals, when the Gestapo arrived. A collaborator had betrayed a group of Jews hiding in the town church’s attic. Eighty Jews were arrested. Others never got word of the upcoming deportations or were too old or incapacitated to seek help. In the end, about 500 Danish Jews were deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto. Of the 500 who were deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto, only 51 did not survive the Holocaust. Still, it was the most successful action of its kind during the Holocaust. Some 7,200 Danish Jews were ferried to Sweden.

The rescue was not without German help either. God can reach people even in such a corrupt government. Werner Best, the German who had been placed in charge of Denmark, apparently tipped off some Jews to the

upcoming action and subtly undermined the Nazis’ attempts to stop the Danes from helping Danish Jews. Another helpful factor was that Denmark was one of the only places in Europe that had successfully integrated its Jewish population. Although there was anti-Semitism in Denmark before and after the Holocaust, the Nazis’ war on Jews was largely viewed as a war against Denmark itself.

upcoming action and subtly undermined the Nazis’ attempts to stop the Danes from helping Danish Jews. Another helpful factor was that Denmark was one of the only places in Europe that had successfully integrated its Jewish population. Although there was anti-Semitism in Denmark before and after the Holocaust, the Nazis’ war on Jews was largely viewed as a war against Denmark itself.

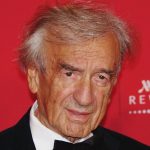

When we look at the events of the Holocaust, we find ourselves looking through the eyes of those who were resigned to their fate. Some even felt like this was what they were born for and nothing could possibly change that. One Holocaust survivor, Eliezer “Elie” Wiesel, who was born in Sighet, Romania, on September 30, 1928 expressed that very sentiment concerning his time as a prisoner of the Nazi Regime. Wiesel’s early life was fairly normal, as it was a fairly peaceful time for the Jewish people. He was part of an average Jewish family consisting of his mother, father, and three sisters, but all that came to a screeching halt in 1944, when they were shipped off to the Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland. The Holocaust experience was so horrific and such an assault on both his body and mind, that it defined his life. He couldn’t even stand to talk about much of it for over 60 years.

When we look at the events of the Holocaust, we find ourselves looking through the eyes of those who were resigned to their fate. Some even felt like this was what they were born for and nothing could possibly change that. One Holocaust survivor, Eliezer “Elie” Wiesel, who was born in Sighet, Romania, on September 30, 1928 expressed that very sentiment concerning his time as a prisoner of the Nazi Regime. Wiesel’s early life was fairly normal, as it was a fairly peaceful time for the Jewish people. He was part of an average Jewish family consisting of his mother, father, and three sisters, but all that came to a screeching halt in 1944, when they were shipped off to the Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland. The Holocaust experience was so horrific and such an assault on both his body and mind, that it defined his life. He couldn’t even stand to talk about much of it for over 60 years.

Wiesel, when he could finally speak of the atrocious acts he and others were subjected to, told of how the Nazi Regime conditioned the prisoners in the camps to believe that their future was what it was, and that they had no say in it. When his own father was beaten in front of him, Wiesel just stood there. He was horrified, but he didn’t move…he didn’t dare. For years that life moment haunted him. His father told him that it wasn’t so bad, but as his father’s son, Wiesel knew he should have done something. Nevertheless, he like so many other Jewish prisoners of the Nazi Regime, was made to understand that the killer (Nazis) came to kill, and the victim (Jews) came to be killed…like it was their destiny from the beginning of time. Somehow they were taught that this was the reason they were born. They are expected to believe that that their life had no other purpose, and that their voice didn’t matter…that their lives didn’t matter.

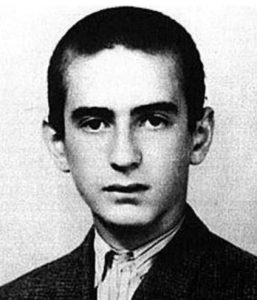

Wiesel’s ordeal really began in 1940, at age 12, when Hungary, which was in alliance with Nazi Germany, annexed his hometown of Sighet, Romania…although he didn’t know it then. At first things seemed ok, but then all the Jews in the city were forced into a ghetto. This was the story so many Jews shared. By 1944, when Elie was 15, Hungary colluded with Germany to deport all residents of the ghetto to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, in Poland. They were trucked out of their homes, their possessions stolen, and then they were packed into a cattle car on a train. It was so tight that they had to stand up the whole trip. They had no food or water, and no restroom facilities. It was terribly degrading. Upon arrival at Auschwitz, Elie’s mother, Sarah, and youngest sister, Tzipora, were killed, and he and his father, Shlomo, were separated from his other sisters, Hilda and Beatrice. Elie and Shlomo were transferred to Buchenwald concentration camp, where his father died.

Then came some of the worst scenes he can remember. Wiesel describes it this way: “Not far from us, flames, huge flames, were rising from a ditch. Something was being burned there. A truck drew close and unloaded its hold: small children. Babies! Yes, I did see this, with my own eyes…children thrown into the flames. (Is it any wonder that ever since then, sleep tends to elude me?)” Wiesel battled with immense guilt and the ugliness of humanity for most of his life after surviving the Holocaust. Nevertheless, Wiesel was devoted to combating indifference, intolerance, and injustice. He became an accomplished writer, professor, and overall champion for human rights. Finally on April 16, 1945, American military personnel liberated the Buchenwald concentration camp. The survivors were barely alive, and even solid food ran the risk of causing their death, because their digestive systems were not prepared for much food, even though they were starving. The soldiers didn’t know the consequences, and gave them chocolate bars. The results were disastrous. They finally had to stop giving them anything, which was just as hard, if not harder than the problems caused by feeding them.

Thinking his family was gone, Wiesel eventually made his way to Paris, where he enrolled in the Sorbonne to study literature, philosophy, and psychology. By age 19, he was working as a journalist for a French newspaper, earing $16 per month…a pretty goo wage in those days. A few years later, in 1949, he was sent to Israel, to cover the early days of the new nation. Wiesel found out that two of his sisters survived, when his sister, Hilda saw his picture in a newspaper. While Elie was living in a French orphanage in 1947, a journalist took his photo, and it was published in the French newspaper where Hilda saw it. In an interview in 2000, Wiesel admitted he thought all his sisters had died in the Holocaust. “When I was still in Buchenwald, I studied the lists of survivors, and my sisters’ names were not there. That’s why I went to France…otherwise I would have gone back to my hometown of Sighet. In France, a clerk in an office at the orphanage told me that he had talked with my sister, who was looking for me. ‘That’s impossible!’ I told him. ‘How would she even know I am in France?’ But he insisted that she’d told him that she would be waiting for me in Paris the next day. I didn’t sleep that night. The next day, I went to Paris, and there was my older sister! After our liberation, she had

gotten engaged and gone to France, because she thought I was dead too. Then one day she opened the paper and saw my picture [a journalist had come to the orphanage to take pictures and write a story]. If it hadn’t been for that, it may have been years before we met. My other sister had gone back to our hometown after our release, thinking that I might be there.” The following year, Elie reunited with Beatrice, in Antwerp, Belgium. She eventually emigrated to Canada, where she lived for the rest of her life. Elie Wiesel passed away on July 2, 2016.

gotten engaged and gone to France, because she thought I was dead too. Then one day she opened the paper and saw my picture [a journalist had come to the orphanage to take pictures and write a story]. If it hadn’t been for that, it may have been years before we met. My other sister had gone back to our hometown after our release, thinking that I might be there.” The following year, Elie reunited with Beatrice, in Antwerp, Belgium. She eventually emigrated to Canada, where she lived for the rest of her life. Elie Wiesel passed away on July 2, 2016.

During the Holocaust, the majority of known Jews in any given country, had a very slim chance of surviving the war, but the Denmark Jews somehow managed to hold an impressive 95% survival rate record. Much of that was due to one man, Georg Ferdinand Duckwitz, who became an unlikely hero of the Jewish people…mainly because he was a German diplomat serving as an attaché for Nazi Germany in occupied Denmark at the time. In fact, that is what makes what he did so strange.

During the Holocaust, the majority of known Jews in any given country, had a very slim chance of surviving the war, but the Denmark Jews somehow managed to hold an impressive 95% survival rate record. Much of that was due to one man, Georg Ferdinand Duckwitz, who became an unlikely hero of the Jewish people…mainly because he was a German diplomat serving as an attaché for Nazi Germany in occupied Denmark at the time. In fact, that is what makes what he did so strange.

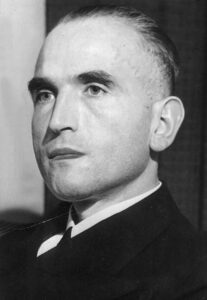

Duckwitz was born on September 29, 1904, in Bremen, Germany. He was part of an old patrician family in the Hanseatic City. After college, he began a career in the international coffee trade. From 1928 until 1932 Duckwitz lived in Copenhagen, Denmark. Upon moving back to Bremen, November 1932 he met Gregor Strasser, who was the leader of the leftist branch of the German nationalistic Nazi Party. While talking to Strasser, Duckwitz found that “elements of Scandinavian socialism [were] connected with nationalistic feelings” and this led to his decision to join the Nazi Party, and subsequently on July 1, 1933, to join the Nazi Party’s Office of Foreign Affairs in Berlin.

What had at first seemed to him to be a party who’s values agreed with his, he soon became increasingly disillusioned by Nazi politics. In a letter written June 4, 1935 to Alfred Rosenberg, the head of the office, he wrote, “My two-year employment in the Reichsleitung [i.e. executive branch] of the [Nazi Party] has made me realize that I am so fundamentally deceived in the nature and purpose of the National Socialist movement that I am no longer able to work within this movement as an honest person.” That move in itself strikes me now, as scary, considering how the known Nazi party functioned. He may not have realized hoe dangerous his words were, but I think they could have gotten him killed. Around the same time the Gestapo (secret police) made its first notes on Duckwitz after he sheltered three Jewish women in his Kurfürstendamm apartment during a local anti-Semitic Sturmabteilung event. He later wrote that during this time period he became “a fierce opponent of this [Nazi] system”.

After 1942, Duckwitz worked with the Nazi Reich representative Werner Best, who organized the Gestapo. On September 11, 1943 Best told Duckwitz about the intended round-up of all Danish Jews on October 1, 1943. A horrified Duckwitz travelled to Berlin in an attempt to stop the deportation through official channels. When that failed, he flew to Stockholm two weeks later, saying he was going to discuss the passage of German merchant ships. While there, he contacted Prime Minister Per Albin Hansson and asked whether Sweden would be willing to receive Danish Jewish refugees. A couple of days later, Hansson came back with the promise of a favorable reception. On September, 29, 1943, Duckwitz contacted Danish social democrat Hans Hedtoft and notified him of the intended deportation. Hedtoft warned the head of the Jewish community CB Henriques and the acting chief rabbi Marcus Melchior, who spread the warning. Sympathetic Danes in all walks of life organized an immediate mass escape of over 7,200 Jews and 700 of their non-Jewish relatives by sea to Sweden. Duckwitz’ immediate action and the willingness of the Danish and Swedish citizens saved the lives of 95% of Denmark’s Jewish population. They were the only European nation to save almost all their Jewish population from certain death at the hand’s of Hitler’s evil regime.

Somehow, Duckwitz was never caught committing his act of “treason” against the Third Reich, and he stayed in good standing with the Nazi regime. After the war, Duckwitz remained in the German foreign service. From 1955– 1958 Duckwitz served as West German ambassador to Denmark and later as the ambassador to India. When Willy Brandt became Foreign Minister in 1966, he made Duckwitz Secretary of State in West Germany´s Foreign Office. After Brandt became Chancellor, he asked Duckwitz to negotiate an agreement with the Polish government. Brandt’s work culminated in the 1970 Treaty of Warsaw. Duckwitz worked as Secretary of State until his final retirement in 1970. On March 21, 1971 the Israeli government named him Righteous Among the Nations and included him in the Yad Vashem memorial. He died two years later, on February 16, 1973 at the age of 68.

1958 Duckwitz served as West German ambassador to Denmark and later as the ambassador to India. When Willy Brandt became Foreign Minister in 1966, he made Duckwitz Secretary of State in West Germany´s Foreign Office. After Brandt became Chancellor, he asked Duckwitz to negotiate an agreement with the Polish government. Brandt’s work culminated in the 1970 Treaty of Warsaw. Duckwitz worked as Secretary of State until his final retirement in 1970. On March 21, 1971 the Israeli government named him Righteous Among the Nations and included him in the Yad Vashem memorial. He died two years later, on February 16, 1973 at the age of 68.

Most people would not think that the things Dr Gisella Perl did at Auschwitz during the Holocaust were angelic in any way, but the prisoners there, the women whose lives she saved would say otherwise. To them, she was an angel of mercy…even if some of the things she had to do were so horrific that she tried to commit suicide after the war. Dr Perl was a successful Jewish gynecologist from Romania, where she lived with her husband and two children. Right before the Nazi soldiers stormed her home, she was able to hid her daughter with some non-Jews, but she, her husband, son, her elderly parents who captured and taken to Auschwitz. Once they arrived, Gisella was separated from her family. They would be sent to be slave labor or to be killed. She would never see any of them again. Because she was a doctor, she was to be used in a different way…a horrifically gruesome way. She was to work for Dr Joseph Mengele, to be at his beck and call, and the things he made her do nearly killed her. She was a doctor. She was supposed to save lives, not be involved in ending them…or worse, but that was the position he put her in.

Most people would not think that the things Dr Gisella Perl did at Auschwitz during the Holocaust were angelic in any way, but the prisoners there, the women whose lives she saved would say otherwise. To them, she was an angel of mercy…even if some of the things she had to do were so horrific that she tried to commit suicide after the war. Dr Perl was a successful Jewish gynecologist from Romania, where she lived with her husband and two children. Right before the Nazi soldiers stormed her home, she was able to hid her daughter with some non-Jews, but she, her husband, son, her elderly parents who captured and taken to Auschwitz. Once they arrived, Gisella was separated from her family. They would be sent to be slave labor or to be killed. She would never see any of them again. Because she was a doctor, she was to be used in a different way…a horrifically gruesome way. She was to work for Dr Joseph Mengele, to be at his beck and call, and the things he made her do nearly killed her. She was a doctor. She was supposed to save lives, not be involved in ending them…or worse, but that was the position he put her in.

First, he told her to round up any pregnant women. She thought she was going to be caring for these women, but after she turned over 50 women, and they were immediately sent to the gas chambers, a horrified Dr Perl made up her mind that somehow, she would do whatever she could to thwart the Nazis horrible plans. She had not understood what was goin to happen to the pregnant women she turned over, and the thought of her part in their loss of live, nearly killed her. The things she did after that first horrible mistake, might not seem to most people, including me, like the actions of an angel, but I can see that she had no real choices.

The women Dr Perl cared for had been treated horrible by the Nazi soldiers. Their wounds consisted of lashes from a whip on bare skin, to bites from dogs, to infections from the horribly unsanitary conditions. When she entered the room, the prisoners in the infirmary knew that she was there to help. That was the good part of her life at Auschwitz, but Dr Mengele was a cruel and evil man, and he was determined to kill any pregnant woman. This left Dr Perl with an extremely difficult decision to make. She could watch as the mother and baby were put to death, or she could abort the babies and give the mothers the chance to live to have a family later. The choice was unthinkable to her, but it was also a non-choice. She could lose one life or both. The abortions were performed in secret, often in darkness, and the women whose lives she saved…well, they were grateful, even

though they mourned their babies and never truly got over the decisions they and Dr Perl made. Later in life, after the war, Dr Perl went on to deliver many live babies, rejoicing over each. She was bold with God, telling him, when a baby seemed unlikely to make it, that God owed her this baby, because of those she could not save in the Holocaust. God honored her prayers, and gave her the healthy babies she requested of Him. I think He considered her the Angel of Auschwitz too.

though they mourned their babies and never truly got over the decisions they and Dr Perl made. Later in life, after the war, Dr Perl went on to deliver many live babies, rejoicing over each. She was bold with God, telling him, when a baby seemed unlikely to make it, that God owed her this baby, because of those she could not save in the Holocaust. God honored her prayers, and gave her the healthy babies she requested of Him. I think He considered her the Angel of Auschwitz too.