helicopter

My sister-in-law, Jennifer Parmely’s partner, Brian Cratty is probably as close as I’ll ever know to a true mountain man. No, he doesn’t live alone in the wilderness, but he probably could. He loves the mountains, loves spending countless hours up at their cabin on Casper Mountain or riding the biking trails, or watching the animals that live and roam through their property. Brian is totally in his element on the mountain. I’m sure that his love of the outdoors is a big part of the attraction for Jennifer. She is a serious outdoor woman too. They always have similar goals and ideas too.

My sister-in-law, Jennifer Parmely’s partner, Brian Cratty is probably as close as I’ll ever know to a true mountain man. No, he doesn’t live alone in the wilderness, but he probably could. He loves the mountains, loves spending countless hours up at their cabin on Casper Mountain or riding the biking trails, or watching the animals that live and roam through their property. Brian is totally in his element on the mountain. I’m sure that his love of the outdoors is a big part of the attraction for Jennifer. She is a serious outdoor woman too. They always have similar goals and ideas too.

Brian is a very compassionate, kind, and loving. He can usually read a situation and knows very well what  needs to be done to comfort people. That was really one of the first things I saw in him, when my father-in-law (Jennifer’s dad) passed away. He was there for her…a quiet strength. It was much appreciated by all of us. We all felt his compassion. That was such a hard day, as were the days following the loss of our other parents, but that day stood out in my mind, because he just made us all feel…loved.

needs to be done to comfort people. That was really one of the first things I saw in him, when my father-in-law (Jennifer’s dad) passed away. He was there for her…a quiet strength. It was much appreciated by all of us. We all felt his compassion. That was such a hard day, as were the days following the loss of our other parents, but that day stood out in my mind, because he just made us all feel…loved.

Brian is a good man. He plays with Jennifer’s grandchildren, making them feel special. He is a wonderful grandpa to them. I’m not sure what the kids call Brian, but in keeping with the German word for Grandma (Oma), I would assume it might be Opa. It doesn’t really matter, because the kids love him, and they have a great time with him. Brian is a person who gets along well with just about anyone, and kids pick up on that stuff too.

Brian has been a pilot for most of his life. He was a helicopter pilot in the US Army, from October 1968 to April

1971. Then when he got out of the Army, he became a Life Flight pilot at Wyoming Medical Center (Banner Health) from October 1984 to December 2006. When he left Banner Health, he flew for Business Aviators, Inc from December 2006 to 2015, when he retired. These days, he is still a pilot, but a lot of his “flying” is done on a bicycle. Today is Briam’s birthday. Happy birthday Brian!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

1971. Then when he got out of the Army, he became a Life Flight pilot at Wyoming Medical Center (Banner Health) from October 1984 to December 2006. When he left Banner Health, he flew for Business Aviators, Inc from December 2006 to 2015, when he retired. These days, he is still a pilot, but a lot of his “flying” is done on a bicycle. Today is Briam’s birthday. Happy birthday Brian!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

There have been many firsts that our United States Presidents have been able to celebrate. One such first was “the first president to ride in a helicopter.” That particular first honor went to a well-known general turned president…Dwight D Eisenhower. On July 12, 1957, President Eisenhower became that first United States president to fly in a helicopter when a United States Air Force H-13J-BF Sioux, serial number 57-2729 (c/n 1576). The helicopter was piloted by Major Joseph E Barrett, USAF. It departed the White House lawn for Camp David, the presidential retreat in the Catoctin Mountains of Maryland. Of course, no presidential trip happens without a Secret Service agent, also on board. On that same day, a second H-13J, 57-2728 (c/n 1575), followed the first, this one carrying President Eisenhower’s personal physician and a second Secret Service agent.

There have been many firsts that our United States Presidents have been able to celebrate. One such first was “the first president to ride in a helicopter.” That particular first honor went to a well-known general turned president…Dwight D Eisenhower. On July 12, 1957, President Eisenhower became that first United States president to fly in a helicopter when a United States Air Force H-13J-BF Sioux, serial number 57-2729 (c/n 1576). The helicopter was piloted by Major Joseph E Barrett, USAF. It departed the White House lawn for Camp David, the presidential retreat in the Catoctin Mountains of Maryland. Of course, no presidential trip happens without a Secret Service agent, also on board. On that same day, a second H-13J, 57-2728 (c/n 1575), followed the first, this one carrying President Eisenhower’s personal physician and a second Secret Service agent.

While that first flight was really a pleasure ride, the main purpose of the helicopter was to rapidly move the  president from the White House to Andrews Air Force Base where his Lockheed VC-121E Constellation, Columbine III, would be standing by. This was intended to be a way of escape to Andrews or to other secure facilities in case of an emergency. Major Barrett was selected as the pilot because of his extensive experience as a combat pilot. They needed someone who was a capable pilot under pressure, a skill that Major Barrett proved he possessed during World War II, when he flew the B-17 Flying Fortress four-engine heavy bomber. Major Barrett was credited with carrying out a helicopter rescue 70 miles behind enemy lines during the Korean War. For his heroics, he was awarded the Silver Star.

president from the White House to Andrews Air Force Base where his Lockheed VC-121E Constellation, Columbine III, would be standing by. This was intended to be a way of escape to Andrews or to other secure facilities in case of an emergency. Major Barrett was selected as the pilot because of his extensive experience as a combat pilot. They needed someone who was a capable pilot under pressure, a skill that Major Barrett proved he possessed during World War II, when he flew the B-17 Flying Fortress four-engine heavy bomber. Major Barrett was credited with carrying out a helicopter rescue 70 miles behind enemy lines during the Korean War. For his heroics, he was awarded the Silver Star.

Not only was the helicopter a great way to quickly secure the president, but that original pilot was the perfect person to make sure that the president was safely transferred to that secure location. The President of the United States is always in a degree of danger. It goes with the territory I suppose. It is the job of his security details is to make sure that no threats are ever able to be carried out. They are very loyal and would die to protect the president.

The Bell Helicopter Company of Fort Worth, Texas, manufactured two of the helicopters. They were delivered to the Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base on March 29, 1957. The two presidential H-13Js were nearly identical to the commercial Bell Model 47J Ranger. They were capable of carrying a pilot and up to three passengers. An enclosed cabin was built on a tubular steel framework with all-metal semi-monocoque tail boom. The main rotor was 37 feet 2 inches in diameter and tail rotor was 5 feet 10.13 inches, making the helicopter an overall length of 43 feet 3¾ inches with rotors turning. It stood 9 feet 8 inches and weighed 2,800 pounds.

When the United States Army sends in the Army Special Forces, they are sending their very best people. It’s not that all of our soldiers aren’t the best in the world, because they are, but the Special Forces, also known as the “Green Berets” due to their distinctive service headgear, are a special operations force of the United States Army that are “designed to deploy and execute nine doctrinal missions: unconventional warfare, foreign internal defense, direct action, counter-insurgency, special reconnaissance, counter-terrorism, information operations, counterproliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and security force assistance. The first two missions, unconventional warfare and foreign internal defenses, emphasize language, cultural, and training skills in working with foreign troops. Other Special Forces missions, known as secondary missions, include: combat search and rescue (CSAR), counter-narcotics, hostage rescue, humanitarian assistance, humanitarian demining, information operations, peacekeeping, and manhunts.” Normally, the Special Forces teams are the ones sent in to rescue the other

When the United States Army sends in the Army Special Forces, they are sending their very best people. It’s not that all of our soldiers aren’t the best in the world, because they are, but the Special Forces, also known as the “Green Berets” due to their distinctive service headgear, are a special operations force of the United States Army that are “designed to deploy and execute nine doctrinal missions: unconventional warfare, foreign internal defense, direct action, counter-insurgency, special reconnaissance, counter-terrorism, information operations, counterproliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and security force assistance. The first two missions, unconventional warfare and foreign internal defenses, emphasize language, cultural, and training skills in working with foreign troops. Other Special Forces missions, known as secondary missions, include: combat search and rescue (CSAR), counter-narcotics, hostage rescue, humanitarian assistance, humanitarian demining, information operations, peacekeeping, and manhunts.” Normally, the Special Forces teams are the ones sent in to rescue the other  soldiers, or at least to drag them out of a sticky situation, but on this occasion, it was the Special Forces team that needed to be rescued.

soldiers, or at least to drag them out of a sticky situation, but on this occasion, it was the Special Forces team that needed to be rescued.

While returning to base from another mission, Air Force 1st Lieutenant James P Fleming and four other Bell UH-1F helicopter pilots received an urgent message from an Army Special Forces team. The pilots were told that the team was pinned down by enemy fire. Several of the other helicopter pilots had to leave the area because they were low on fuel, but Lieutenant Fleming and another pilot pressed on with the rescue effort. While the first attempt failed because of intense ground fire, they refused to abandon the Army green berets. Then, Fleming managed to land and pick up the team. Against all odds, he safely arrived at his base near Duc Co, at which time it was discovered that his helicopter was nearly out of fuel. For his lifesaving efforts, Lieutenant Fleming was later awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions. It was a selfless act, that could have cost him his life, but Lieutenant Fleming didn’t even consider his own life. He only thought about the others.

Our instincts tell us not to leave a man down, or behind. That doesn’t just apply just to military personnel. Nevertheless, military personnel have had that concept ingrained into their being…probably more so than the rest of us. It is a code for them…never leave a man behind…whenever they have any say about it, they don’t. 1st Lieutenant James P Fleming was no different. In fact, Fleming was exceptional. Fleming was a helicopter pilot during the Vietnam War. On November 26, 1968, Fleming and four other UH-1F helicopter pilots were returning to their base at Duc Co, South Vietnam, for refueling and rearming when an emergency call for help was received from a Special Forces reconnaissance team.

Our instincts tell us not to leave a man down, or behind. That doesn’t just apply just to military personnel. Nevertheless, military personnel have had that concept ingrained into their being…probably more so than the rest of us. It is a code for them…never leave a man behind…whenever they have any say about it, they don’t. 1st Lieutenant James P Fleming was no different. In fact, Fleming was exceptional. Fleming was a helicopter pilot during the Vietnam War. On November 26, 1968, Fleming and four other UH-1F helicopter pilots were returning to their base at Duc Co, South Vietnam, for refueling and rearming when an emergency call for help was received from a Special Forces reconnaissance team.

While en route, they got a call that a six-man Special Forces team was pinned down by a large, hostile force not far from a river bank. The homebound force of two gunships and three transport helicopters immediately changed course and sped to the area without refueling. As the gunships descended to attack the enemy positions, one was hit and downed. The remaining gunship made several passes, rapidly firing with its miniguns, but the intense  return fire from enemy machine guns continued. Finally, low on fuel, the helicopters were being forced to leave and return to base.

return fire from enemy machine guns continued. Finally, low on fuel, the helicopters were being forced to leave and return to base.

Lieutenant Fleming alone remained as the only transport helicopter left. He descended over the river to evacuate the team. Upon arrival, he found the area unsafe for landing because of the dense foliage, so he hovered just above the river with his landing skids braced against the bank. The lone gunship continued its strafing runs, but heavy enemy fire prevented the team from reaching the helicopter. Fleming’s leader advised him to withdraw. After pulling away, Lieutenant Fleming decided to make another rescue attempt before completely exhausting his fuel. He dropped down to the same spot and found that the team had managed to move closer to the river bank. The men dashed out and clambered aboard as bullets pierced the air, some  smashing into the helicopter. The rescue craft and the gunship then returned to Duc Co where it was discovered that they were nearly out of fuel.

smashing into the helicopter. The rescue craft and the gunship then returned to Duc Co where it was discovered that they were nearly out of fuel.

It was truly a miraculous rescue, in which not a single life was lost. Lieutenant Fleming was awarded the Medal of Honor for saving the lives of the special forces team that day. For his actions, Fleming received the Medal of Honor in May, 1970. Fleming remained in the Air Force serving a total of 30 years, becoming a colonel and a member of the Officer Training School staff at Lackland Air Force Base, Texas, before his retirement in 1996 at the rank of Colonel.

On October 13, 1972 a plane crashed somewhere in the Andes Mountains. That isn’t such an unusual event, but the crash was the last part of this event that was not unusual. Flight 571 was en route from Uruguay to Chili at the time it went down. The Uruguayan Air Force plane was chartered by the Old Christians Club to transport the team from Montevideo, Uruguay to Santiago, Chile. On October 12 the twin-engined Fairchild turboprop left Carrasco International Airport. The plane was carrying 5 crew members and 40 passengers. In addition to club members…friends, family, and others were also on board, having been recruited to help pay the cost of the plane. Because of poor weather in the mountains, they were forced to stay overnight in Mendoza, Argentina, before departing at about 2:18 pm the following day, October 13th. Although Santiago was located to the west of Mendoza, the Fairchild was not built to fly higher than approximately 22,500 feet. Because the Andes mountains were higher than that, the pilots plotted a course south to the Pass of Planchón, where the aircraft could safely clear the Andes mountains. An hour after takeoff, the pilot notified air controllers that he was flying over the pass, and shortly thereafter he radioed that he had reached Curicó, Chile, some 110 miles south of Santiago, and had turned north. However, the pilot had misjudged the location of the aircraft, which was still in the Andes mountains. Unaware of the mistake, the controllers cleared him to begin descending in preparation for landing. Then suddenly, the Chilean control tower was unable to contact the plane.

On October 13, 1972 a plane crashed somewhere in the Andes Mountains. That isn’t such an unusual event, but the crash was the last part of this event that was not unusual. Flight 571 was en route from Uruguay to Chili at the time it went down. The Uruguayan Air Force plane was chartered by the Old Christians Club to transport the team from Montevideo, Uruguay to Santiago, Chile. On October 12 the twin-engined Fairchild turboprop left Carrasco International Airport. The plane was carrying 5 crew members and 40 passengers. In addition to club members…friends, family, and others were also on board, having been recruited to help pay the cost of the plane. Because of poor weather in the mountains, they were forced to stay overnight in Mendoza, Argentina, before departing at about 2:18 pm the following day, October 13th. Although Santiago was located to the west of Mendoza, the Fairchild was not built to fly higher than approximately 22,500 feet. Because the Andes mountains were higher than that, the pilots plotted a course south to the Pass of Planchón, where the aircraft could safely clear the Andes mountains. An hour after takeoff, the pilot notified air controllers that he was flying over the pass, and shortly thereafter he radioed that he had reached Curicó, Chile, some 110 miles south of Santiago, and had turned north. However, the pilot had misjudged the location of the aircraft, which was still in the Andes mountains. Unaware of the mistake, the controllers cleared him to begin descending in preparation for landing. Then suddenly, the Chilean control tower was unable to contact the plane.

The pilot basically found himself caught with high mountains all around him…mountains that he could not climb over. When the plane tried to climb out the wings were clipped by the peaks, and the plane crashed in an unknown location. Because the Chilean control tower thought the plane was much further south, they weren’t even sure where to look. To make matters worse, the white plane was extremely difficult to see against the white snow. Search and rescue efforts from the sky were almost impossible…despite the survivors’ attempts to become noticeable. After 11 days, it was assumed that all of the 45 passengers and crew were dead, so search and rescue efforts ceased. The passengers had access to a radio, and when they heard the news of the search  being called off, they were devastated. The crash killed 12 people instantly, leaving 33 survivors to try to stay alive until help could come. A number of the survivors were injured. At an altitude of approximately 11,500 feet, the group faced snow and freezing temperatures. There was no heat, and they only had each other to depend on. While the plane’s fuselage was largely intact, it provided limited protection from the freezing temperatures they faced. Food was scarce…mainly candy bars and wine. Even with rationing, those were gone in about a week. Now the survivors faced the most horrifying decision of their lives. Do they stay alive at all costs, including eating the bodies of the dead for food, or do they simply give up and starve to death? After a heated discussion, the starving survivors resorted to eating the corpses. Their survival instincts had kicked in, even though they knew they might be condemned by the world. Nevertheless, they would probably never forgive themselves anyway, so what the world decided made no real difference. Over the next few weeks six others died, and further disaster struck on October 29, when an avalanche buried the fuselage and filled part of it with snow, causing eight more deaths.

being called off, they were devastated. The crash killed 12 people instantly, leaving 33 survivors to try to stay alive until help could come. A number of the survivors were injured. At an altitude of approximately 11,500 feet, the group faced snow and freezing temperatures. There was no heat, and they only had each other to depend on. While the plane’s fuselage was largely intact, it provided limited protection from the freezing temperatures they faced. Food was scarce…mainly candy bars and wine. Even with rationing, those were gone in about a week. Now the survivors faced the most horrifying decision of their lives. Do they stay alive at all costs, including eating the bodies of the dead for food, or do they simply give up and starve to death? After a heated discussion, the starving survivors resorted to eating the corpses. Their survival instincts had kicked in, even though they knew they might be condemned by the world. Nevertheless, they would probably never forgive themselves anyway, so what the world decided made no real difference. Over the next few weeks six others died, and further disaster struck on October 29, when an avalanche buried the fuselage and filled part of it with snow, causing eight more deaths.

It was decided that someone would have to walk out and tell the officials that they were still alive. On December 12, with just 16 people still alive, three passengers set out for a 10 day journey to find help, though one later returned to the wreckage. After a difficult trek, the other two men finally came across three herdsmen in the village of Los Maitenes, Chile, on December 20. However, the Chileans were on the opposite side of a river, the noise of which made it hard to hear. The herdsmen indicated that they would return the following day. Early the next morning, the Chileans reappeared, and the two groups communicated by writing notes on paper that they then wrapped around a rock and threw across the water. The survivors’ initial note began, “I come from a plane that fell in the mountains.” The Chileans must have heard about the crash, and were most likely stunned to find that there were actually survivors. They hurried to notified authorities, and on December 22 two helicopters were sent to the wreckage. Six survivors were flown to safety, but bad weather delayed the eight others from being rescued until the next day. The  rescue was called the Miracle of the Andes. In the resulting media frenzy, the survivors revealed that they had been forced to commit cannibalism. Many people were outraged until one of the survivors claimed that they had been inspired by the Last Supper, in which Jesus gave his disciples bread and wine that he stated were his body and his blood. This helped soften public opinion, and the church later absolved the men. After watching the movie based on this event, I wondered how any of the rest of us would have handled that situation. We should never be too quick to judge people in such a situation, because we might find that given the same circumstances, we might do the exact same thing.

rescue was called the Miracle of the Andes. In the resulting media frenzy, the survivors revealed that they had been forced to commit cannibalism. Many people were outraged until one of the survivors claimed that they had been inspired by the Last Supper, in which Jesus gave his disciples bread and wine that he stated were his body and his blood. This helped soften public opinion, and the church later absolved the men. After watching the movie based on this event, I wondered how any of the rest of us would have handled that situation. We should never be too quick to judge people in such a situation, because we might find that given the same circumstances, we might do the exact same thing.

Sometimes in life, a person has the unique opportunity to basically go full circle. It’s not exactly like going back to your roots, because many people have done that…myself included. Sometimes though, as in the case with my youngest grandson, Josh Petersen and his dad, Kevin, you have the opportunity to go back to a birth event, and see it in an entirely different light. When Josh was born on September 9, 1998…five weeks early, his lungs just weren’t quite strong enough to maintain his oxygen levels without assistance. It was decided that he would be taken to Presbyterian Saint Luke’s Hospital in Denver, Colorado via Life Flight’s Learjet. Since his mother, my daughter Corrie Petersen has just given birth, after serious attempts to stop it, the doctors felt it would be best for her to spend the night in the hospital here. So it was decided that Kevin would fly to Denver with Josh, and my husband Bob and I would bring Corrie, and their oldest son, Chris to Denver the next day, when she was released. It was a traumatic event for everyone involved, especially for Chris, who was 2½ at the time.

Sometimes in life, a person has the unique opportunity to basically go full circle. It’s not exactly like going back to your roots, because many people have done that…myself included. Sometimes though, as in the case with my youngest grandson, Josh Petersen and his dad, Kevin, you have the opportunity to go back to a birth event, and see it in an entirely different light. When Josh was born on September 9, 1998…five weeks early, his lungs just weren’t quite strong enough to maintain his oxygen levels without assistance. It was decided that he would be taken to Presbyterian Saint Luke’s Hospital in Denver, Colorado via Life Flight’s Learjet. Since his mother, my daughter Corrie Petersen has just given birth, after serious attempts to stop it, the doctors felt it would be best for her to spend the night in the hospital here. So it was decided that Kevin would fly to Denver with Josh, and my husband Bob and I would bring Corrie, and their oldest son, Chris to Denver the next day, when she was released. It was a traumatic event for everyone involved, especially for Chris, who was 2½ at the time.

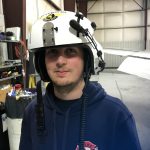

Fast forward now…eighteen years and seven months later, to the present. After spending two weeks in the hospital in Denver, Josh went on to become a healthy young man, who wants to be a fire fighter and EMT…small wonder. Josh has always had a helpers heart, and has assisted in caregiving for years with great grandparents. He has a gentle way, and he is meticulous in proper caregiving. He has been taking fire fighting courses through the Boces program at his high school, and in the fall will continue working toward his degree in Fire Science. He will also be training in EMT in the very near future.

Fast forward now…eighteen years and seven months later, to the present. After spending two weeks in the hospital in Denver, Josh went on to become a healthy young man, who wants to be a fire fighter and EMT…small wonder. Josh has always had a helpers heart, and has assisted in caregiving for years with great grandparents. He has a gentle way, and he is meticulous in proper caregiving. He has been taking fire fighting courses through the Boces program at his high school, and in the fall will continue working toward his degree in Fire Science. He will also be training in EMT in the very near future.

A few days ago, his dad talked to a friend, Clancy, from high school, who just happens to work for Life Flight now. They got on the subject of Josh, and Clancy offer to give them a tour. For Josh and for Kevin, this was like going full circle…not just to the hospital or the city Josh was born in, which he still lives in, but back to the service that took them on that life saving journey to Denver. They were given a tour of both the Life Flight

Helicopter and the Life Flight Learjet. I can’t say for sure that this jet was the same as the one Josh and Kevin traveled in initially, but if not it was probably exactly like that one. For Josh, I’m sure this was another step in his journey to his career, but since he has heard his story before, I’m sure that was in the back of his mind too. For Kevin, I wonder if there was a memory of that worried feeling in the pit of his stomach, but then I’m sure there was also a feeling of gratitude, both for saving his son’s life, and giving him such a wonderful tour. Josh…well, he was excited to be right where he wants to be.

Helicopter and the Life Flight Learjet. I can’t say for sure that this jet was the same as the one Josh and Kevin traveled in initially, but if not it was probably exactly like that one. For Josh, I’m sure this was another step in his journey to his career, but since he has heard his story before, I’m sure that was in the back of his mind too. For Kevin, I wonder if there was a memory of that worried feeling in the pit of his stomach, but then I’m sure there was also a feeling of gratitude, both for saving his son’s life, and giving him such a wonderful tour. Josh…well, he was excited to be right where he wants to be.