germans

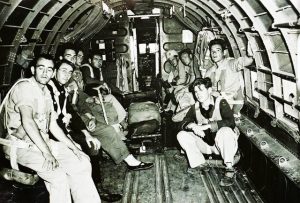

On January 24, 1944, the first of over 500 American airmen bailed out of their disabled planes over the German-occupied zone of Serbia. That first day, the Germans shot down two Liberators…one over Zlatibor and the other over Toplica. One bomber made an emergency landing between Plocnik and Beloljin. That crew of nine men were rescued by the Chetnik Toplica Corps under the command of Major Milan Stojanovic. The crew were placed in the home of local Chetnik leaders in the village of Velika Dragusa. The other bomber crew bailed out over Mount Zlatibor. They were found by members of the Zlatibor Corps. A radiogram message on the rescue of one of the crews was sent by Stojanovic to Mihailovic on January 25th. Major Stojanovic wrote that the previous day about 100 bombers flew from the direction of Nis towards Kosovska Mitrovica, and that they were followed by nine German fighter aircraft. After a half-hour battle, one plane caught fire and was forced to land between the villages of Plocnik and Beloljin, in the Toplica River valley.

On January 24, 1944, the first of over 500 American airmen bailed out of their disabled planes over the German-occupied zone of Serbia. That first day, the Germans shot down two Liberators…one over Zlatibor and the other over Toplica. One bomber made an emergency landing between Plocnik and Beloljin. That crew of nine men were rescued by the Chetnik Toplica Corps under the command of Major Milan Stojanovic. The crew were placed in the home of local Chetnik leaders in the village of Velika Dragusa. The other bomber crew bailed out over Mount Zlatibor. They were found by members of the Zlatibor Corps. A radiogram message on the rescue of one of the crews was sent by Stojanovic to Mihailovic on January 25th. Major Stojanovic wrote that the previous day about 100 bombers flew from the direction of Nis towards Kosovska Mitrovica, and that they were followed by nine German fighter aircraft. After a half-hour battle, one plane caught fire and was forced to land between the villages of Plocnik and Beloljin, in the Toplica River valley.

Over the next few months, more planes were shot down, and more crews were rescued by the Serbian resistance. In all it was thought that 432 men had been hidden, effectively saving them from the German prison camps. In the end, it was determined that the actual number of men in need of rescue was 512. The men had no way of knowing that they would be “guests” of the Serbian resistance for 7 long months, and in some cases longer.

The two resistance groups, Marshal Tito’s Partisans and Draza Mihailovic’s Chetniks, both hated the Nazis vehemently, and they also hated each other. It made working together difficult at best. Still, they shared a common goal…to defeat the Nazis, and they were willing to do what was necessary to achieve that goal. While it was sometimes possible to smuggle the airmen out and reunite them with their units, it was not always possible. When they could not get the men out, they kept them in their homes, and shared what little food they had with them.

In July 1944, these men again came to the attention of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), and they began to draw up plans to bring the men home. I’m sure by then, the men thought they really had been forgotten, or maybe that no one knew about them at all, but now they were going to be going home. Operation Halyard, the operation to bring home these men, commenced on August 9, 1944 and continued until December 28, 1944. The men would be airlifted out of Serbia 12 men at a time, but before any airlift could take place, they had to build an airstrip. The C-47 cargo plane required 700 feet of runway for takeoffs and landings. The men and the  people of Serbia built an airstrip that was exactly 700 feet long. It was bordered by forest and mountains, so the takeoffs and landings would have to be precise. According to historian Professor Jozo Tomasevich, a report submitted to the OSS showed that 417 Allied airmen who had been downed over occupied Yugoslavia were rescued by Mihailovic’s Chetniks, and airlifted out by the Fifteenth Air Force. According to Lieutenant Commander Richard M Kelly (OSS), a grand total of 432 United States and 80 Allied personnel were airlifted during the Halyard Mission. In the end, at least in this mission, the military lived up to its motto, “Never leave a man behind.”

people of Serbia built an airstrip that was exactly 700 feet long. It was bordered by forest and mountains, so the takeoffs and landings would have to be precise. According to historian Professor Jozo Tomasevich, a report submitted to the OSS showed that 417 Allied airmen who had been downed over occupied Yugoslavia were rescued by Mihailovic’s Chetniks, and airlifted out by the Fifteenth Air Force. According to Lieutenant Commander Richard M Kelly (OSS), a grand total of 432 United States and 80 Allied personnel were airlifted during the Halyard Mission. In the end, at least in this mission, the military lived up to its motto, “Never leave a man behind.”

When Natalia Peshkova was a girl in high school, during the early years of World War II, women were not allowed to join the Russian Army. Nevertheless, the women of Russia wanted to help, just like women from most of the Allied nations. As the war went on, the need for soldiers brought women into the draft…like it or not. Peshkova found herself recruited right out of high school, and at the age of 17, she was set to be a combat medic.

When Natalia Peshkova was a girl in high school, during the early years of World War II, women were not allowed to join the Russian Army. Nevertheless, the women of Russia wanted to help, just like women from most of the Allied nations. As the war went on, the need for soldiers brought women into the draft…like it or not. Peshkova found herself recruited right out of high school, and at the age of 17, she was set to be a combat medic.

Things were tough in the arena Peshkova found herself in. The poorly equipped unit was faced with weapons that continuously malfunctioned…not a good thing to defend yourself with. Peshkova’s stint in the Russian army was filled with constant disease, starvation, and even the loss of a boot to a hungry horse, while she slept. To say the least, life in the Russian army was tough.

Despite the hardships, Peshkova did her duty as a combat medic, protecting and helping soldiers that were wounded on the front lines as much as she could. Her training taught her to protect wounded soldiers from the front and get them safely to hospitals, often placing herself in possible harm’s way. While she was trained to apply first aid, her main duty was always to remove wounded men from the front line. Trying to do first aid on the front lines was a dangerous maneuver for both soldier and medic. Peshkova was wounded three times for her efforts, but she had a kind of strength and determination that was unmatched in the field, and she always returned to the front when she had healed. I’m sure many people thought she was half crazy.

At one point, Peshkova got separated from her unit, finding herself behind enemy lines when the Germans took over territory previously held by the Russians. She had to act fast, so she disguised herself, while also hiding her weapon, because if she discarded it, she would have been executed by her own military. She finally made it back to her unit and survived three years on the front lines. She rose through the ranks to become Sergeant Major, and was then given political education duties that finally relived her from life on the front lines. Natalia Peshkova was truly one of a kind, and was awarded the Order of the Red Star for Bravery.

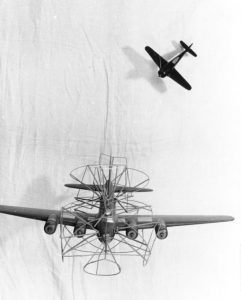

When the B-17 was built, it was designed to be a formidable weapon against the enemy, namely the Nazis and the Japanese. Early on, before long-range fighter escorts came into being, B-17s had only their .50 caliber M2, the B-17s were on their own out there. Still, the B-17 was not defenseless. With those .50 caliber M2s, the crew had the ability to fire at the enemy from every direction…almost. The job of the Messerschmitt fighters was to take down the B-17s. The Messerschmitt fighter planes were designed to break world air speed records. They were also the hope of the Germans to take down the B-17s. Still, there were all those guns to deal with. Luftwaffe fighter pilots agreed that attacking a B-17 combat box formation to encountering a fliegendes Stachelschwein, “flying porcupine,” with dozens of machine guns in a combat box aimed at them from almost every direction. The biggest downfall of the B-17 bombing formation was that they had to fly straight, making them vulnerable to German flak. It was the first line of defense the Germans had when the bombers came in.

When the B-17 was built, it was designed to be a formidable weapon against the enemy, namely the Nazis and the Japanese. Early on, before long-range fighter escorts came into being, B-17s had only their .50 caliber M2, the B-17s were on their own out there. Still, the B-17 was not defenseless. With those .50 caliber M2s, the crew had the ability to fire at the enemy from every direction…almost. The job of the Messerschmitt fighters was to take down the B-17s. The Messerschmitt fighter planes were designed to break world air speed records. They were also the hope of the Germans to take down the B-17s. Still, there were all those guns to deal with. Luftwaffe fighter pilots agreed that attacking a B-17 combat box formation to encountering a fliegendes Stachelschwein, “flying porcupine,” with dozens of machine guns in a combat box aimed at them from almost every direction. The biggest downfall of the B-17 bombing formation was that they had to fly straight, making them vulnerable to German flak. It was the first line of defense the Germans had when the bombers came in.

In a 1943 survey, the USAAF found that over half the bombers shot down by the Germans had left the protection of the main formation. The Germans needed a training plan. The United States developed the bomb-group formation, which evolved into the staggered combat box formation in which all the B-17s could safely cover any others in their formation with their machine guns, making a formation of bombers a dangerous target to engage by enemy fighters. The Messerschmitt fighters were fast, but they could not just fly at the formation. They would be shot down for sure. So, they looked for the bomber that had been hit and had to pull out of formation. Then they would move in for the kill. Moreover, German fighter aircraft later developed the tactic of high-speed strafing passes rather than engaging with individual aircraft to inflict damage with minimum risk. It was a way of not fully engaging the “flying porcupine.” As a result, the B-17s’ loss rate was up to 25% on some early missions. They needed something more to provide a kind of shield against the enemy.

It was not until the advent of long-range fighter escorts (particularly the North American P-51 Mustang) and the resulting degradation of the Luftwaffe as an effective interceptor force between February and June 1944, that the B-17 became strategically potent. They needed the P-15 Mustang to keep the Messerschmitts off of them. So in the end, the German training didn’t do them much good against the “flying porcupine.”

When Hitler began his systematic genocide of the Jewish people during World War II, many of the previously free people found themselves suddenly jailed. They had no weapons with which to fight for their freedom, but they knew that they were going to have to make a decision to either fight for their lives, or lose their lives. Some were too old or too young to fight, and some were women, and many men didn’t think these women could handle the fight at hand, but at some point they would have to fight or die. Hitler was relentless, and the Jewish people were fighting for their lives.

When Hitler began his systematic genocide of the Jewish people during World War II, many of the previously free people found themselves suddenly jailed. They had no weapons with which to fight for their freedom, but they knew that they were going to have to make a decision to either fight for their lives, or lose their lives. Some were too old or too young to fight, and some were women, and many men didn’t think these women could handle the fight at hand, but at some point they would have to fight or die. Hitler was relentless, and the Jewish people were fighting for their lives.

When Hitler set his plan in motion, he made it impossible for them to do business. Overnight, all Jewish businesses were blackballed. That was how it started anyway. The Jewish people were no longer allowed to do business with non-Jews. That action meant that the income that these successful Jewish people had, was instantly taken from them…symbolically. Later, It would be taken in every way. Their shops were looted, their property confiscated, and their homes given to others. As the Jewish people were banished to the ghettos, they had just moments to pack a small bag with the things they could carry, or more importantly the things they couldn’t do without…clothing, any food items, and keepsakes. It wasn’t much. There wasn’t room for much.

The ghettos were complete pits of filth, disease, and humanity. People were piled into cramped quarters, forced to share living quarters with people they didn’t know. Of course, the tight quarters was not the worst thing about the ghettos. The people had no rights. If a Nazi soldier raped, beat, or shot a Jewish person, there was no punishment, because they were no longer considered human, and therefore had no rights. Although it was considered an abomination to sleep with a Jewish person, rape was actually considered just another form of punishment. The Nazis didn’t care. A death meant one less Jew to have to house.

The Warsaw ghetto in Poland occupied an area of less than two square miles but soon held almost 500,000  Jews in the deplorable conditions common to ghettos. Disease and starvation killed thousands every month, and when death did not come fast enough, the Jews were transferred to the next level of their torture. Beginning in July 1942, 6,000 Jews per day were transferred to the Treblinka concentration camp. They went by way of cattle cars, packed so tightly that it was standing room only. In fact, if a prisoner died along the way, their body remained standing…held up by the people so tightly packed in around them.

Jews in the deplorable conditions common to ghettos. Disease and starvation killed thousands every month, and when death did not come fast enough, the Jews were transferred to the next level of their torture. Beginning in July 1942, 6,000 Jews per day were transferred to the Treblinka concentration camp. They went by way of cattle cars, packed so tightly that it was standing room only. In fact, if a prisoner died along the way, their body remained standing…held up by the people so tightly packed in around them.

As word got back to the ghettos that the death rate of those being transferred to the camps, either on the trains, or in the gas chambers when they reached their final destination, the Jewish people knew that something was going to have to be done. They would have to fight for their lives. Of course, the resistance was already working. There were those who saw the writing on the wall from the start. When word came down that the Warsaw ghetto was going to be closed and the Jews deported to the camps, it was time.

On January 18, 1943, as Nazi forces were attempting to clear out the Warsaw ghetto they were met by gunfire from Jewish resistance fighters. Although the Nazis assured the remaining Jews that their relatives and friends were being sent to work camps, they no longer believed the Nazi lies. An underground resistance group had been established in the ghetto, called the Jewish Combat Organization (ZOB). Limited arms had been acquired at great cost, and it didn’t matter, because this was a fight to the death. As the Nazis entered, the ZOB unit ambushed them, killing a number of German soldiers. The fighting lasted for several days.

On January 18, 1943, when the Nazis entered the ghetto to transport a group of Jewish prisoners, a ZOB unit ambushed them. Fighting lasted for several days, and a number of Germans soldiers were killed before they withdrew. On April 19th, Heinrich Himmler announced that the ghetto was to be emptied of its residents in honor of Hitler’s birthday the next day. I guess Himmler thought murdering all those people would make a great birthday gift for Hitler. That day, more than 1,000 SS soldiers entered the confines of the ghetto, armed with tanks and heavy artillery. Of the 60,000 Jews remaining in the ghetto hid in secret bunkers, more than 1,000 of the ZOB resistance members took up arms and fought back with gunfire and homemade bombs. Again the soldiers withdrew, despite only suffering moderate casualties. Then on April 24th, the Germans and launched an all-out attack against the Warsaw Jews.

The German soldiers stormed through the ghetto, blowing up buildings everywhere. They slaughtered thousands of innocent people. The ZOB took to the sewers to continue the fight. It was cover, but how awful. Then, on May 8th their command bunker fell to the Germans and their resistant leaders committed suicide. I’m sure they thought they had failed their people. By May 16th, the ghetto was firmly under Nazi control, and the last Warsaw Jews were deported to Treblinka. Some 300 German soldiers were killed, and thousands of Warsaw Jews were massacred during the Warsaw Uprising, but that wasn’t the end of the death. Virtually all those who survived the Uprising to reach Treblinka were dead by the end of the war.

The German soldiers stormed through the ghetto, blowing up buildings everywhere. They slaughtered thousands of innocent people. The ZOB took to the sewers to continue the fight. It was cover, but how awful. Then, on May 8th their command bunker fell to the Germans and their resistant leaders committed suicide. I’m sure they thought they had failed their people. By May 16th, the ghetto was firmly under Nazi control, and the last Warsaw Jews were deported to Treblinka. Some 300 German soldiers were killed, and thousands of Warsaw Jews were massacred during the Warsaw Uprising, but that wasn’t the end of the death. Virtually all those who survived the Uprising to reach Treblinka were dead by the end of the war.

When I think of some of the civilian heroes of our wars, I find myself amazed at the many courageous acts they carried out. They threw caution to the wind and moved about among the enemy, somehow managing to remain almost invisible. They had code names and secret pasts that no one knew about, not even the people they worked with…and definitely not the enemy they worked against.

When I think of some of the civilian heroes of our wars, I find myself amazed at the many courageous acts they carried out. They threw caution to the wind and moved about among the enemy, somehow managing to remain almost invisible. They had code names and secret pasts that no one knew about, not even the people they worked with…and definitely not the enemy they worked against.

One of these spies was Nancy Grace Augusta Wake, who was also known by her married name, Nancy Fiocca. Wake was a New Zealand-born nurse and journalist, who joined the French Resistance and later the Special Operations Executive (SOE) during World War II. Born August 30, 1912 in Roseneath, Wellington, New Zealand, the youngest of the six children of Charles Augustus Wake and Ella Rosieur Wake. In 1914, the family moved to Australia and settled at North Sydney. Shortly thereafter, Wake’s father returned to New Zealand and her mother raised the children. In Sydney, Wake attended the North Sydney Household Arts (Home Science) School.

At the age of 16, she ran away from home and worked as a nurse. With £200 (about $255.27) that she had inherited from an aunt, she traveled to New York City, then London where she trained herself as a journalist. In the 1930s, she worked in Paris and later for Hearst newspapers as a European correspondent. She witnessed the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi movement and “saw roving Nazi gangs randomly beating Jewish men and women in the streets” of Vienna. The Nazi movement repulsed her.

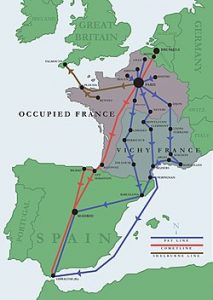

In 1937, Wake met wealthy French industrialist Henri Edmond Fiocca, whom she married on November 30, 1939. They were living in Marseille, France when Germany invaded. During the war in France, Wake served as an ambulance driver. After the fall of France in 1940, she joined the French Resistance, working in the escape network of Captain Ian Garrow, which became the Pat O’Leary Line. Wake had an incredible ability to elude capture, which earned her the nickname, “White Mouse” by the Gestapo. The Resistance exercised caution with her missions, because her life was in constant danger. The Gestapo tapped her telephone and intercepted her mail. In spite of the danger, Wake said, “I don’t see why we women should just wave our men a proud goodbye and then knit them balaclavas.” As a member of the escape network, she helped Allied airmen evade capture by the Germans and escape to neutral Spain.

In November 1942, Wehrmacht troops occupied the southern part of France after the Allies’ Operation Torch had started. This gave the Germans and the Gestapo unrestricted access to all parts of Vichy France and made life more dangerous for Wake. When the network was betrayed that same year she decided to flee France. Her husband, Henri Fiocca, stayed behind. He later was captured, tortured, and executed by the Gestapo. She threw caution to the wind. She would “doll” herself up and be very flirtatious, almost daring them to search her. She took a chance, and they couldn’t see past her façade to the ruthless spy beneath the beauty she showed on the outside.

In 1943, when the Germans became aware of her, she escaped to Spain and continued on to the United Kingdom. After reaching Britain, Wake joined the Special Operations Executive (SOE) under the code name Hélène. On April 29-30, 1944 as a member of a three person SOE team code-named “Freelance,” Wake parachuted into the Allier department of occupied France to liaise between the SOE and several Maquis groups in the Auvergne region, which were loosely overseen by Emile Coulaudon (code name “Gaspard”). She participated in a battle between the Maquis and a large German force in June 1944. In the aftermath of the battle, she bicycled 500 kilometers to send a situation report to SOE in London. In early 1943, in the process of getting out of France, Wake was picked up with a whole trainload of people and was arrested in Toulouse, but was released four days later. The head of the O’Leary Line, Albert Guérisse, managed to have her released by claiming she was his mistress and was trying to conceal her infidelity to her husband (all of which was untrue). She succeeded in crossing the Pyrenees to Spain. Until the war ended, she was unaware of her husband’s death, and she subsequently blamed herself for it. Wake was a recipient of the George Medal from the United Kingdom, the Medal of Freedom from the United States, the Legion of Honor from France, and medals from Australia and New Zealand.

In 1985, Wake published her autobiography, “The White Mouse.” Later, after 40 years of marriage, her second husband John Forward died at Port Macquarie on 19 August 1997. The couple had no children. Wake sold her medals to fund herself saying, “There was no point in keeping them, I’ll probably go to hell and they’d melt anyway.” Strangely, this disregard of the value of war medals, seemed common among the war spies. In 2001, Wake left Australia for the last time and emigrated to London. She became a resident at the Stafford Hotel in Saint James’ Place, near Piccadilly, formerly a British and American forces club during the war. She had been introduced to her first “bloody good drink” there by Louis Burdet, the general manager at the time, who had  also worked for the Resistance in Marseille. Mornings usually found Wake in the hotel bar, sipping her first gin and tonic of the day. She was welcomed at the hotel, celebrating her ninetieth birthday there. Out of deep respect for her, the hotel owners absorbed most of the costs of her stay. In 2003, Wake chose to move to the Royal Star and Garter Home for Disabled Ex-Service Men and Women, in Richmond, London, where she remained until her death on Sunday evening August 7, 2011, aged 98, at Kingston Hospital, where she had been admitted with a chest infection. She had requested that her ashes be scattered at Montluçon in central France. Her ashes were scattered near the village of Verneix, which is near Montluçon, on March 11, 2013.

also worked for the Resistance in Marseille. Mornings usually found Wake in the hotel bar, sipping her first gin and tonic of the day. She was welcomed at the hotel, celebrating her ninetieth birthday there. Out of deep respect for her, the hotel owners absorbed most of the costs of her stay. In 2003, Wake chose to move to the Royal Star and Garter Home for Disabled Ex-Service Men and Women, in Richmond, London, where she remained until her death on Sunday evening August 7, 2011, aged 98, at Kingston Hospital, where she had been admitted with a chest infection. She had requested that her ashes be scattered at Montluçon in central France. Her ashes were scattered near the village of Verneix, which is near Montluçon, on March 11, 2013.

When we think of war heroes, civilians seldom come to mind. The reality is that there are many, many civilian heroes in any war. Each of those civilian heroes has their own reasons to take the actions they take. The one similarity is that most of them simply cannot continue to support a government that is committing the atrocities they commit, and so they have to take action, or they can’t look themselves in the mirror again. Sometimes, a change of heart comes because they see the cruelty of the country they live in. Other times, the change comes when they see that their countrymen are not even safe from their own government. Finally, completely disillusioned, they find themselves without alternative options, when they come face to face with the enemy within their own boarders.

When we think of war heroes, civilians seldom come to mind. The reality is that there are many, many civilian heroes in any war. Each of those civilian heroes has their own reasons to take the actions they take. The one similarity is that most of them simply cannot continue to support a government that is committing the atrocities they commit, and so they have to take action, or they can’t look themselves in the mirror again. Sometimes, a change of heart comes because they see the cruelty of the country they live in. Other times, the change comes when they see that their countrymen are not even safe from their own government. Finally, completely disillusioned, they find themselves without alternative options, when they come face to face with the enemy within their own boarders.

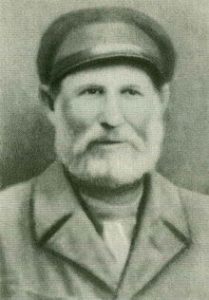

Matvey Kuzmich Kuzmin was born on August 3, 1858 in the village of Kurakino, in the Velikoluksky District of Pskov Oblast. He was a self-employed farmer who declined the offer to join a kolkhoz or collective farm. He lived with his grandson and continued to hunt and fish on the territory of the kolkhoz “Rassvet” (Dawn). He was nicknamed “Biriuk” (lone wolf).

During World War II, the area Kuzmin lived in was occupied by the forces of Nazi Germany. In February 1942, Kuzmin had to help house a German battalion in the village of Kurakino. The German unit was ordered to pierce the Soviet defense in the area of Velikiye Luki by advancing into the rear of the Soviet troops dug in at Malkino Heights. Kuzmin had to do what he had to do…like it or not. On February 13, 1942, the German commander asked the 83 year old Kuzmin to guide his men to the Malkino Heights area, and even offered Kuzmin money, flour, kerosene, and a “Three Rings” hunting rifle for doing so. Kuzmin agreed, but he knew that with information on the proposed route, he could make a difference. He sent his grandson Vasilij to Pershino, about 3.5 miles from Kurakino, to warn the Soviet troops and to propose an ambush near the village of Malkino.

The plan was for Kuzmin to guide the German units through straining paths, through the night. He lead them to  the outskirts of Malkino at dawn. When they arrived, the village defenders and the 2nd battalion of 31st Cadet Rifle Brigade of the Kalinin Front attacked. The German battalion came under heavy machine gun fire and suffered losses of about 50 killed and 20 captured. In the midst of the ambush, a German officer realized that they had been set up and turned his pistol towards Kuzmin. He shot him twice. Kuzmin died during the fight. He was buried three days later with military honors. Later, he was reburied at the military cemetery of Velikiye Luki. He was posthumously named a Hero of the Soviet Union on May 8, 1965, becoming the oldest person named a Hero of the Soviet Union based on his age at death.

the outskirts of Malkino at dawn. When they arrived, the village defenders and the 2nd battalion of 31st Cadet Rifle Brigade of the Kalinin Front attacked. The German battalion came under heavy machine gun fire and suffered losses of about 50 killed and 20 captured. In the midst of the ambush, a German officer realized that they had been set up and turned his pistol towards Kuzmin. He shot him twice. Kuzmin died during the fight. He was buried three days later with military honors. Later, he was reburied at the military cemetery of Velikiye Luki. He was posthumously named a Hero of the Soviet Union on May 8, 1965, becoming the oldest person named a Hero of the Soviet Union based on his age at death.

In a war, the point is to kill the enemy, or be killed by the enemy. There is no room for soft hearts and compassion…or is there? On December 20, 1943, Charlie Brown, an American B-17 bomber pilot and his crew attempted to bomb an aircraft production facility in Bremen, Germany, as part of a bombing run with a squadron of B-17s. Unfortunately, the interior areas of Germany were better fortified with anti-aircraft guns. As the bombing run reached the factory, and dropped the payload, the 250 anti-aircraft guns which surrounded the factory were fired. Charlie Brown’s B-17, Ye Olde Pub, was hit, disabling two engines and forcing the plane out of formation. It was the habit of the German fighter planes to go after any stragglers, knowing that they were the weaker link. Brown’s damaged B-17 was chased down and several of the crew members were seriously wounded. The hit also knocked out all but one of the plane’s engines.

In a war, the point is to kill the enemy, or be killed by the enemy. There is no room for soft hearts and compassion…or is there? On December 20, 1943, Charlie Brown, an American B-17 bomber pilot and his crew attempted to bomb an aircraft production facility in Bremen, Germany, as part of a bombing run with a squadron of B-17s. Unfortunately, the interior areas of Germany were better fortified with anti-aircraft guns. As the bombing run reached the factory, and dropped the payload, the 250 anti-aircraft guns which surrounded the factory were fired. Charlie Brown’s B-17, Ye Olde Pub, was hit, disabling two engines and forcing the plane out of formation. It was the habit of the German fighter planes to go after any stragglers, knowing that they were the weaker link. Brown’s damaged B-17 was chased down and several of the crew members were seriously wounded. The hit also knocked out all but one of the plane’s engines.

Thinking the plane was doomed, the fighters turned their attention to other prey. Meanwhile, Ye Olde Pub tried to limp along toward England, hoping not to be spotted. Of course, they knew their hope of escape was quite unlikely, and before long they were spotted by German fighter pilot Franz Stigler, who was refueling. Stigler jumped into his plane and took off, catching up with the wounded plane quickly. Stigler was about to blast the plane, when he saw that the crew was seriously wounded. Stigler, a combat veteran with 22 confirmed kills, was reluctant to attack a defenseless aircraft, so instead pulled alongside the B-17 cockpit and signaled the crew to land. They refused. He then motioned in the direction of Sweden, which would get them on the ground, but also take them out of the war. It didn’t really matter, because the Allied crew didn’t understand.

Unable to convince them to land, but also unwilling to leave them, Stigler flew side-by-side with the stricken bomber, even though he was afraid his own plane might identify him, and his actions might get him executed. As Brown’s B-17 approached the safety of the English Channel, Stigler saluted and peeled off…not really expecting the B-17 to make it safely home. Miraculously, Brown kept the plane in the air and made it to England. Brown  often wondered why Stigler hadn’t shot him down, but never expected to know who the unknow German fighter pilot was. Nevertheless, after the war, Brown placed an ad in a World War II newsletter for pilot veterans. Amazingly, Stigler, who had relocated to Canada, saw the ad. The two pilots reunited, both still in shock to see the other, and when Brown ask the question that had been burning in his mind for years…why didn’t Stigler shoot them down? Stigler explained that to shoot at them would have been dishonorable. Charlie Brown was shocked to know that even among the enemy, there could exist such compassion. The two pilots immediately felt like they were forever connected. They remained close friends until their deaths in 2008.

often wondered why Stigler hadn’t shot him down, but never expected to know who the unknow German fighter pilot was. Nevertheless, after the war, Brown placed an ad in a World War II newsletter for pilot veterans. Amazingly, Stigler, who had relocated to Canada, saw the ad. The two pilots reunited, both still in shock to see the other, and when Brown ask the question that had been burning in his mind for years…why didn’t Stigler shoot them down? Stigler explained that to shoot at them would have been dishonorable. Charlie Brown was shocked to know that even among the enemy, there could exist such compassion. The two pilots immediately felt like they were forever connected. They remained close friends until their deaths in 2008.

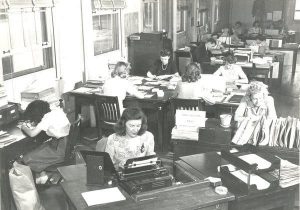

During World War II, when men were in short supply due to deployments, and the secret codes of the Japanese and Germans were causing major problems, the American government was faced with a difficult decision. They needed people who were qualified to break the codes of their enemies, and the only code breakers were in very short supply. The decision was made to search out college-educated women, preferably with degrees in Mathematics, Physics, and those who were fluent in other languages. There weren’t a lot of college educated women in those days, and even fewer with degrees in math or physics, but there were teachers. The Navy and the Army began recruiting these women. The women were required to go through a battery of tests and interviews to see if they had what it took to become code breakers. Many did not, but those who did were offered an exciting, but stressful career.

During World War II, when men were in short supply due to deployments, and the secret codes of the Japanese and Germans were causing major problems, the American government was faced with a difficult decision. They needed people who were qualified to break the codes of their enemies, and the only code breakers were in very short supply. The decision was made to search out college-educated women, preferably with degrees in Mathematics, Physics, and those who were fluent in other languages. There weren’t a lot of college educated women in those days, and even fewer with degrees in math or physics, but there were teachers. The Navy and the Army began recruiting these women. The women were required to go through a battery of tests and interviews to see if they had what it took to become code breakers. Many did not, but those who did were offered an exciting, but stressful career.

Upon arrival in Washington DC, these women found themselves in direct competition with the men, and the men didn’t like it one bit. Nevertheless, the feelings the men had for these women who were a threat to their  job, was at least matched by what the public thought of these women who, sworn to secrecy, had to lie about the work they did. They told people they were secretaries, and glorified waitresses, bring coffee to their bosses, while adding a bit of “interest” to the office. People thought these women were “loose” women…”gold diggers” looking for a husband, and because of the deep need for security, the women were forced to let people think what they wanted too.

job, was at least matched by what the public thought of these women who, sworn to secrecy, had to lie about the work they did. They told people they were secretaries, and glorified waitresses, bring coffee to their bosses, while adding a bit of “interest” to the office. People thought these women were “loose” women…”gold diggers” looking for a husband, and because of the deep need for security, the women were forced to let people think what they wanted too.

No matter what the public thought, these women code breakers were a vital part of the war effort. Our men were dying because we had no idea where the ships and submarines were until they struck. These women turned the tables in favor of the Allies, though few people ever knew it. The women were told they must never speak of what they did there…even after the war, and most of them took their secrets to the grave. While the women were forced to keep their secrets, they all knew that what they were doing mattered. They also knew things about the war, that others didn’t know. They knew the danger the Allied ships were in. They knew about ship that were torpedoed, almost as soon as it happened, and sometimes the ships were ones that friends and loved ones were stationed on…meaning they knew of their loved ones deaths almost immediately after they were killed.

At great sacrifice to themselves, the women code breakers fought a battle in the war that many people never  knew about. The stress, and just the shear gravity of the situation wore of the women. Some later had to seek psychiatric help, and some had nervous breakdowns, still they kept their secrets, lest their services were ever needed again. They kept them in case they ever had to be used again. They kept them because they had orders, and they would follow their orders no matter what. The work had been tedious, and sometimes codes took a long time to crack, but the determined women stuck it out, although most would never be thanked for their hard work. It didn’t matter. Their work was vital, and they were saving lives. That would have to be enough to carry them through the rest of their lives.

knew about. The stress, and just the shear gravity of the situation wore of the women. Some later had to seek psychiatric help, and some had nervous breakdowns, still they kept their secrets, lest their services were ever needed again. They kept them in case they ever had to be used again. They kept them because they had orders, and they would follow their orders no matter what. The work had been tedious, and sometimes codes took a long time to crack, but the determined women stuck it out, although most would never be thanked for their hard work. It didn’t matter. Their work was vital, and they were saving lives. That would have to be enough to carry them through the rest of their lives.

I have long been interested in war, and especially World War II. Every aspect of it interests me, and I find myself wondering about the enemy. I’m sure that might seem odd to many people, but as we have found in the United States, just because the government goes to war, does not mean that every citizen, or even every soldier agrees with the reasons the country has gone to war. I have been listening to a couple of audiobooks that have taken in D-Day, and I came across something interesting.

I have long been interested in war, and especially World War II. Every aspect of it interests me, and I find myself wondering about the enemy. I’m sure that might seem odd to many people, but as we have found in the United States, just because the government goes to war, does not mean that every citizen, or even every soldier agrees with the reasons the country has gone to war. I have been listening to a couple of audiobooks that have taken in D-Day, and I came across something interesting.

Without going into all of that amazing strategy of warfare, I want to focus on one of the bombing maneuvers that took place. One of the soldiers on the ground was trying to take cover from incoming German bombs. After the bombing stopped, he looked out and was shocked to see eight bombs embedded in the ground near his foxhole. They had not gone off. He knew that it is possible for bombs to be duds, but he hadn’t heard of any American bombs that had turned out to be duds…especially eight of them at the same time, in the same place.  He wasn’t bragging on the American bombs, their craftmanship, or their ingenuity, but rather, wondering how so many German bombs could have been duds…all at the same time.

He wasn’t bragging on the American bombs, their craftmanship, or their ingenuity, but rather, wondering how so many German bombs could have been duds…all at the same time.

Then the soldier made an observation that I had not considered, but that fell right into my view that not everyone in Germany agreed with Hitler. The American bomb builders were doing their job willingly. They were working to make the bombs efficient, because Germany needed to be defeated. In contrast, the German bomb builders were actually Polish slaves. Hitler had invaded their nation and was forcing them to play a part in a war that they disagreed with. The soldier considered these things and came to the conclusion that somehow the Polish slaves had been able to build a bomb that they knew would not explode, but would still pass the inspections of the Germans. The soldier believed that eight unexploded bombs could not be coincidental. It had to be sabotage.

In my research, I have seen situations where the citizens have helped the enemy, at great risk to their own safety. I have seen situations where the citizens have given aid to the enemy. And this situation was a blatant sabotage of the weapons of warfare. Within their nations, these acts were acts of treason, but they were actually fighting the evil that had tried to take over their nation. Within their confines, they were standing up for their values…for good, and for what was right. They were the enemy, in location only, because in their hearts, the were fighting for what was right, and I have to respect them for that.

While researching some of the larger battles of World War II, I began to consider the brilliance of the men who planned these battles. Men like Sir Winston Spencer-Churchill, Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D Eisenhower, Admiral Chester Nimitz, Admiral Frank Fletcher, and Admiral Raymond Spruance (who was a replacement, but proved to be instrumental in the success of Midway). These men and others like them knew that the stakes were high, and by sheer numbers, the Allies were outnumbered by the Axis armies. That said, they also knew that the fate of the world was in their hands. If they lost this war, the Japanese and Germans would quite likely take over and rule the world. Life as we knew it would cease to exist.

While researching some of the larger battles of World War II, I began to consider the brilliance of the men who planned these battles. Men like Sir Winston Spencer-Churchill, Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D Eisenhower, Admiral Chester Nimitz, Admiral Frank Fletcher, and Admiral Raymond Spruance (who was a replacement, but proved to be instrumental in the success of Midway). These men and others like them knew that the stakes were high, and by sheer numbers, the Allies were outnumbered by the Axis armies. That said, they also knew that the fate of the world was in their hands. If they lost this war, the Japanese and Germans would quite likely take over and rule the world. Life as we knew it would cease to exist.

Strategy is everything. Of course, part of that strategy involves something that many Americans have come to hate these days…fake news. These strategic minds knew that somehow they had to fool the Japanese into believing that no attack was coming, or that the advancing armies were headed elsewhere. It sounds simple, but this wasn’t the movies. Nevertheless, information was leaked to the enemy, while the Allied armies advanced as planned. The strategy worked perfectly on D-Day when Hitler was fooled, by men he had called idiots, into thinking that the target was at some point along their Atlantic Wall…the 1,500-mile system of coastal defenses that the German High Command had constructed from the Arctic Circle to Spain’s northern border…or even as far away as the Balkans. Vital to Operation Bodyguard’s success were more than a dozen German spies in Britain who had been discovered, arrested and flipped by British intelligence officers. The Allies  fed faulty information to these Nazi double agents to pass along to Berlin. A pair of double agents nicknamed Mutt and Jeff relayed detailed reports about the fictitious British Fourth Army that was gathering in Scotland with plans to join with the Soviet Union in an invasion of Norway. The Allies also fabricated radio chatter about cold-weather issues such as ski bindings and the operation of tank engines in subzero temperatures. The plan worked as Hitler sent one of his fighting divisions to Scandinavia just weeks before D-Day.

fed faulty information to these Nazi double agents to pass along to Berlin. A pair of double agents nicknamed Mutt and Jeff relayed detailed reports about the fictitious British Fourth Army that was gathering in Scotland with plans to join with the Soviet Union in an invasion of Norway. The Allies also fabricated radio chatter about cold-weather issues such as ski bindings and the operation of tank engines in subzero temperatures. The plan worked as Hitler sent one of his fighting divisions to Scandinavia just weeks before D-Day.

At Midway, the American “Doolittle” raid, a propaganda air attack on Tokyo launched from the carrier USS Hornet, prompted Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto to plan a final showdown with the remnants of the American fleet before letting his forces rest. The “Doolittle” raid had been an insult and it had threatened the life of the emperor. Yamamoto was confident that he had the advantage in numbers and quality to destroy the American carrier fleet. He planned to confuse the enemy with a diversionary attack on the Alaskan coast, drawing the Americans north, only to launch his main attack on Midway Island the following day, which would see the Americans hurrying south, into an ambush. With a great show of overelaboration, which was typical of Japanese military planning. Yamamoto divided his force into three main groups. There were four big carriers, the battlefleet, and the invasion force. These three groups were too far apart for mutual support. The Japanese carrier group operated in close order, commanded by Admiral Nagumo, who had led them for the attack at Pearl Harbor. Nimitz, for his part, could not hope to win a direct engagement. He had to stake everything on exploiting his intelligence windfall, and try to ambush the enemy. He secretly reinforced the air units on Midway, using the island as an unsinkable aircraft carrier. His sea-going carriers were positioned to the

northeast of the island, waiting to ambush the Japanese carriers when they arrived for their assault. The American tactics relied on the peculiar characteristics of carrier warfare. Nimitz knew the first attack would be decisive for either side, carriers being full of fuel and ordnance, hence highly vulnerable to bombs and torpedoes. The American tactical commanders, admirals Frank Fletcher and Raymond Spruance, also knew they were playing for very high stakes. They kept the two task forces separate. The strategy worked, and the Japanese never fully recovered.

northeast of the island, waiting to ambush the Japanese carriers when they arrived for their assault. The American tactics relied on the peculiar characteristics of carrier warfare. Nimitz knew the first attack would be decisive for either side, carriers being full of fuel and ordnance, hence highly vulnerable to bombs and torpedoes. The American tactical commanders, admirals Frank Fletcher and Raymond Spruance, also knew they were playing for very high stakes. They kept the two task forces separate. The strategy worked, and the Japanese never fully recovered.