french

When I think of war and of the largest offensive in United States history, I don’t picture a battle in World War I. Nevertheless, I should. The Meuse–Argonne offensive, which was also called the Meuse River–Argonne Forest offensive, the Battles of the Meuse–Argonne, and the Meuse–Argonne campaign, depending on who you were, was a major part of the final Allied offensive of World War I that stretched along the entire Western Front. The offensive ran for a total of 47 days, from September 26, 1918, until the Armistice of November 11, 1918, and it was the largest in United States military history, past or present.

When I think of war and of the largest offensive in United States history, I don’t picture a battle in World War I. Nevertheless, I should. The Meuse–Argonne offensive, which was also called the Meuse River–Argonne Forest offensive, the Battles of the Meuse–Argonne, and the Meuse–Argonne campaign, depending on who you were, was a major part of the final Allied offensive of World War I that stretched along the entire Western Front. The offensive ran for a total of 47 days, from September 26, 1918, until the Armistice of November 11, 1918, and it was the largest in United States military history, past or present.

The offensive involved 1.2 million American soldiers, and as battles go, it is the second deadliest in American history. During the course of the battle, there were over 350,000 casualties including 28,000 German lives, 26,277 American lives, and an unknown number of French lives. The losses involving the United States were compounded by the inexperience of many of the troops, the tactics used during the early phases of the operation, and in no small way…the widespread onset of the global influenza outbreak called the “Spanish flu.” The 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic, also known as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly

global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The pandemic affected an estimated 500 million people, or approximately a third of the global population. It is estimated that 17 to 50 million, and possibly as high as 100 million people lost their lives, which probably increased the deaths during the Meuse-Argonne offensive.

global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The pandemic affected an estimated 500 million people, or approximately a third of the global population. It is estimated that 17 to 50 million, and possibly as high as 100 million people lost their lives, which probably increased the deaths during the Meuse-Argonne offensive.

The Meuse–Argonne was the principal engagement of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) during World War I, and it was what finally brought the war to an end. It was the largest and bloodiest operation of World War I for the AEF. Nevertheless, by October 31, the Americans had advanced 9.3 miles and had cleared the Argonne Forest. The French advanced 19 miles to the left of the Americans, reaching the Aisne River. The American forces split into two armies at this point. General Liggett led the First Army and advanced to the Carignan-Sedan-Mezieres Railroad. Lieutenant General Robert L Bullard led the Second Army and was directed to move eastward toward Metz. The two United States armies faced portions of 31 German divisions during this phase. The American troops captured German defenses at Buzancy, allowing French troops to cross the Aisne River. There, they rushed forward, capturing Le Chesne, also known as the Battle of Chesne (French: Bataille du Chesne).

In the final days, the French forces conquered the immediate objective, Sedan and its critical railroad hub in a

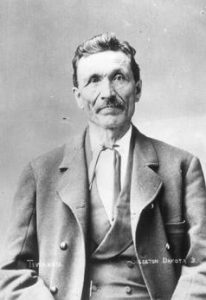

battle known as the Advance to the Meuse (French: Poussée vers la Meuse), and on November 6, American forces captured surrounding hills. On November 11, news of the German armistice put a sudden end to the fighting. That was fortunate for the armies, but for my 1st cousin twice removed, William Henry Davis, it was six days too late. He lost his life on November 5, 1918, on the west bank of the Meuse during these battles. He was just 30 years old at the time.

USS Scorpion (SSN-589) was a Skipjack-class nuclear-powered submarine that served in the United States Navy, and the sixth vessel, and second submarine, of the US Navy to carry that name. It was also the fourth nuclear powered submarine to mysteriously go missing in 1968. Scorpion was lost with all its crew, on May 22, 1968. Scorpion is one of two nuclear submarines the US Navy has lost, the other being USS Thresher. The other nuclear-powered submarines to go missing in 1968 at the height of the Cold War were Israeli submarine INS Dakar, the French submarine Minerve, and the Soviet submarine K-129. At the time Scorpion went missing when she was sent to surveil the Soviet submarine K-129, which had apparently already gone missing earlier in the year. The wreckage of USS Scorpion is still at the bottom of the North Atlantic Ocean…with all its armaments and nuclear engine.

USS Scorpion (SSN-589) was a Skipjack-class nuclear-powered submarine that served in the United States Navy, and the sixth vessel, and second submarine, of the US Navy to carry that name. It was also the fourth nuclear powered submarine to mysteriously go missing in 1968. Scorpion was lost with all its crew, on May 22, 1968. Scorpion is one of two nuclear submarines the US Navy has lost, the other being USS Thresher. The other nuclear-powered submarines to go missing in 1968 at the height of the Cold War were Israeli submarine INS Dakar, the French submarine Minerve, and the Soviet submarine K-129. At the time Scorpion went missing when she was sent to surveil the Soviet submarine K-129, which had apparently already gone missing earlier in the year. The wreckage of USS Scorpion is still at the bottom of the North Atlantic Ocean…with all its armaments and nuclear engine.

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The first phase of the Cold War began shortly after the end of World War II in 1945. The United States and its allies created the NATO military alliance in 1949 in the apprehension of a Soviet attack and termed their global policy against Soviet influence containment.

Following World War II, tensions were running high between world powers. It is thought that if there was ever a time when a real possibility of a nuclear attack existed, it was during the Cold War. This meant that countries were frantically looking for any advantage they could use to take over their competitors. One way to watch the other countries was to Surveil beneath the waves where they could be more hidden. This surveillance included the use of submarine crews. That, of course, explains the reason for mysterious disappearance of four subs from four different countries virtually at the same time.

The first disappearance was the INS Dakar from Israel, which went down just east of Crete on January 25, 1968. Dakar’s wreckage was found in 1991, but no official cause for the sinking was determined. Next, The French sub Minerve disappeared about an hour outside of Toulon on January 27, 1968. That wreckage was found in 2019, and it showed the hull had separated into three sections. When the French government made the decision to leave the wreck, any chance of answers was eliminated. The Soviet K-129 disappeared earlier in the year, so maybe USS Scorpion was looking for it. Nevertheless, on May 22, 1968, the disappearance conspiracy of 1968 was brought to a close, when USS Scorpion. The submarine would not be fount until October of 1968. The Navy looked into the disaster, but in the end the official court of inquiry said the cause of the loss could not be determined with certainty. Still, there are several theories on what might have happened. One centered around a malfunction of a torpedo. Others suspected poor maintenance may have been the culprit, citing the rushed overhaul.

That was the last report anyone heard about the submarine. After decades of research and investigation, the US Navy has never changed its report that a catastrophic event caused the sinking. Nevertheless, there are those who believe the Scorpion was taken out by the Soviets in retaliation for perceived attack on the K-129

submarine earlier in the year. Neither country will admit or deny any direct action relating to the submarine sabotage, but something happened during the first half of 1968. Four nuclear-powered submarines, from four different countries just don’t start sinking for no reason, and yet, no reason was ever determined. They just sunk.

submarine earlier in the year. Neither country will admit or deny any direct action relating to the submarine sabotage, but something happened during the first half of 1968. Four nuclear-powered submarines, from four different countries just don’t start sinking for no reason, and yet, no reason was ever determined. They just sunk.

The pilgrims were not the only people who did not like, or accept, British rule. When the French sold some of their territory to the British, the Indian tribes in these areas were not happy about the new regime. The French had more or less left them alone to do as they chose, and so they tended to live in relative peace, but the British were a different kind of rule, and the Indians felt that they were far less conciliatory than their predecessors. It wasn’t that the French and the Indians got along well, after all they had just ended the French and Indian Wars in the early 1760s. It was simply that the British were more demanding and less giving in the area of the Indian rights, than the French had been.

The pilgrims were not the only people who did not like, or accept, British rule. When the French sold some of their territory to the British, the Indian tribes in these areas were not happy about the new regime. The French had more or less left them alone to do as they chose, and so they tended to live in relative peace, but the British were a different kind of rule, and the Indians felt that they were far less conciliatory than their predecessors. It wasn’t that the French and the Indians got along well, after all they had just ended the French and Indian Wars in the early 1760s. It was simply that the British were more demanding and less giving in the area of the Indian rights, than the French had been.

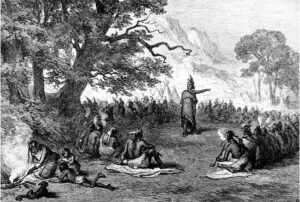

As the matter became more and more heated, an Ottawan Indian chief named Pontiac decided that it was time for the Indian tribes to rebel. So, he called together a confederacy of Native warriors to attack the British force at Detroit. In 1762, Pontiac enlisted support from practically every tribe from Lake Superior to the lower Mississippi for a joint campaign to expel the British from the formerly French-occupied lands. According to Pontiac’s plan, each tribe would seize the nearest fort and then join forces to wipe out the undefended settlements. In April 1763, Pontiac convened a war council on the banks of the Ecorse River near Detroit. It was decided that Pontiac and his warriors would gain access to the British fort at Detroit under the pretense of negotiating a peace treaty, giving them an opportunity to seize forcibly the arsenal there. However, British Major Henry Gladwin learned of the plot, and the British were ready when Pontiac arrived in early May 1763, and Pontiac was forced to begin a siege. His Indian allies in Pennsylvania began a siege of Fort Pitt, while other sympathetic tribes, such as the Delaware, the Shawnees, and the Seneca, prepared to move against various British forts and outposts in Michigan, New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia, at the same time. After failing to take the fort in their initial assault, Pontiac’s forces, made up of Ottawas and reinforced by Wyandots, Ojibwas and Potawatamis, initiated a siege that would stretch into months.

A British relief expedition attacked Pontiac’s camp on July 31, 1763. They suffered heavy losses and were repelled in the Battle of Bloody Run. However, they did succeeded in providing the fort at Detroit with reinforcements and supplies. That victorious battle allowed the fort to hold out against the Indians into the fall. Also holding on were the major forts at Pitt and Niagara, but the united tribes captured eight other fortified posts. At these forts, the garrisons were wiped out, relief expeditions were repulsed, and nearby frontier settlements were destroyed.

Two British armies were sent out in the spring of 1764. One was sent into Pennsylvania and Ohio under Colonel Bouquet, and the other to the Great Lakes under Colonel John Bradstreet. Bouquet’s campaign met with success, and the Delawares and the Shawnees were forced to sue for peace, breaking Pontiac’s alliance. Failing to persuade tribes in the West to join his rebellion, and lacking the hoped-for support from the French, Pontiac finally signed a treaty with the British in 1766. In 1769, he was murdered by a Peoria tribesman while visiting Illinois. His death led to bitter warfare among the tribes, and the Peorias were nearly wiped out.

The port city of my birth, Superior, Wisconsin was founded on November 6, 1854 and incorporated March 25 1889. The city’s slogan soon became, “Where Sail Meets Rail,” because it was port connection between the shipping industry and the railroad. Much of Superior’s history parallels its sister city of Duluth’s, but Superior has been around longer than Duluth, which is also known as the Zenith City. Of course, the area had people there before that…there were Ojibwe Indians, and French traders that are known to be in the area in the early 1600s.

The port city of my birth, Superior, Wisconsin was founded on November 6, 1854 and incorporated March 25 1889. The city’s slogan soon became, “Where Sail Meets Rail,” because it was port connection between the shipping industry and the railroad. Much of Superior’s history parallels its sister city of Duluth’s, but Superior has been around longer than Duluth, which is also known as the Zenith City. Of course, the area had people there before that…there were Ojibwe Indians, and French traders that are known to be in the area in the early 1600s.

After the Ojibwe settled in the area and set up an encampment on present-day Madeline Island, the French started arriving. In 1618 voyageur Etienne Brulé paddled along Lake Superior’s south shore where he encountered the Ojibwe tribe, but he also found copper specimens. Brulé went back to Quebec with the copper samples, and a glowing report of the region. French traders and missionaries began settling the area a short time later, and a Lake Superior tributary was named for Brulé. Father Claude Jean Allouez, was one of those missionaries. His is often credited with the development of an early map of the region. Superior’s Allouez neighborhood takes its name from the Catholic missionary. The area was developed quickly after that, and by 1700 the area was crawling with French traders. The French traders developed a good working relationship with the Ojibwe people.

The Ojibwe continued to get along well with the French, but not so much the British, who ruled the area after

the French, but that ended with the America Revolution and the Treaty of Peace in 1783. The British weren’t as good to the Ojibwe as the French had been. Treaties with the Ojibwe would give more territory to settlers of European descent, and by 1847 the United States had taken control of all lands along Lake Superior’s south shore.

the French, but that ended with the America Revolution and the Treaty of Peace in 1783. The British weren’t as good to the Ojibwe as the French had been. Treaties with the Ojibwe would give more territory to settlers of European descent, and by 1847 the United States had taken control of all lands along Lake Superior’s south shore.

In 1854 the first copper claims were staked at the mouth of the Nemadji River…some say it was actually 1853. The Village of Superior became the county seat of the newly formed Douglas County that same year. The village grew quickly and within two years, about 2,500 people called Superior home. Unfortunately, with the financial panic of 1857, the town’s population stagnated through the end of the Civil War. The building of the Duluth Ship Canal in 1871, which was followed by the Panic of 1873. pretty much crushed Superior’s economic future. Things began to look up when in 1885, Robert Belknap and General John Henry Hammond’s Land and River Improvement Company established West Superior. Immediately they began building elevators, docks, and industrial railroads. In 1890, Superior City and West Superior merged, The city’s population fluctuated, as a boom town will, between 1887 and 1893, and then another financial panic halted progress. Over the years since then, Superior’s population has had it’s ups and down, as has it’s sister city, Duluth, but it has remained about one fourth the size of its twin across the bay.

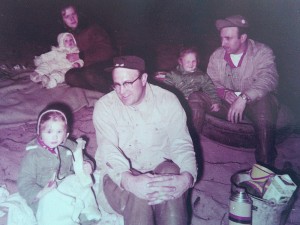

My great grandparents, Carl and Albertine Schumacher lived in the Goodhue, Minnesota area, when my grandmother Anna was born, but my grandparents Allen and Anna Spencer lived in Superior. That is where my

dad, Allen Spencer was born, as were my sister, Cheryl and I. We didn’t live in Superior for all of our lives, just 3 and 5 years, but the area remains in our blood, and in our hearts. It could be partly because of all the trips our family made back to Superior, but I don’t think that’s totally it, because there is just something about knowing that you came from a place, that will always make it special. Superior, Wisconsin is a very special place, that will always be a part of me and my sister, Cheryl too.

dad, Allen Spencer was born, as were my sister, Cheryl and I. We didn’t live in Superior for all of our lives, just 3 and 5 years, but the area remains in our blood, and in our hearts. It could be partly because of all the trips our family made back to Superior, but I don’t think that’s totally it, because there is just something about knowing that you came from a place, that will always make it special. Superior, Wisconsin is a very special place, that will always be a part of me and my sister, Cheryl too.

Recently I read a novel that was based on a true story, called “The Alice Network,” by Kate Quinn. Knowing the book was a novel, I assumed that it was entirely fictional, but then I began to wonder, so I researched “The Alice Network” for myself. I found that “The Alice Network” was a very much true story, even if some of the characters in the story were fictional. The head of the Alice Network, Louise Marie Jeanne Henriette de Bettignies, was very much a real person.

Recently I read a novel that was based on a true story, called “The Alice Network,” by Kate Quinn. Knowing the book was a novel, I assumed that it was entirely fictional, but then I began to wonder, so I researched “The Alice Network” for myself. I found that “The Alice Network” was a very much true story, even if some of the characters in the story were fictional. The head of the Alice Network, Louise Marie Jeanne Henriette de Bettignies, was very much a real person.

Louise Marie Jeanne Henriette de Bettignies was born on July 15, 1880 to Henri de Bettignies and Julienne Mabille de Poncheville. She was fluent in French and English, with a good mastery in German and Italian. It made her a perfect candidate for the spy network. Louise became a French secret agent who spied on the Germans for the British during World War I using the pseudonym of Alice Dubois, hence “The Alice Network.” She had under her direction, a number of men and women who mainly worked in the area of Lille, in German occupied France. Her people listened inconspicuously to the talk of the German soldiers when they were not aware, and therefore, not careful to guard their tongues. The gleaned intel was then passed to couriers, of which Louise was one, to be transported by car, train, or on foot to the military leaders they worked for. It was a dangerous occupation, but the spies in the network wanted to serve in the war effort, and this was their chance.

Spies in “The Alice Network” and other such networks, went to work in jobs that were basically normal everyday jobs. They became waitresses, singers, shop workers, all in areas frequented by the enemy. They swallowed their disgust, in order to become almost invisible to the Germans. They never told anyone that they spoke German, because the Germans felt comfortable talking in front of these people who, they thought, couldn’t understand a word they said. It gave the spy networks just the edge they needed. Some spies, like Louise, spent time in makeshift hospitals writing letters in German dictated by dying Germans to their families. Dying men aren’t always careful with the information they give. A wealth of information was passed from these networks to the intelligence officers, and it often proved to be invaluable.

Louise lived with her sister, Germaine at 166 rue d’Isly. From October 4 to 13, 1914, by turning the only cannon that the Lille troops had, the defenders succeeded in deceiving the enemy and holding them for several days under an intense battle that destroyed more than 2,200 buildings and houses, particularly in the area of the station. Louise de Bettignies, aged 28, making full use of the four languages she spoke, including German and English. Through the ruins of Lille, she ensured the supply of ammunition and food to the soldiers who were still firing on the attackers. Then, since she had been a citizen of Lille since 1903, Louise made the decision in October 1914, to engage in resistance and espionage. Due in part to her ability to speak French, English, German, and Italian, she ran a vast intelligence network from her home in the North of France on behalf of the British army and the MI6 intelligence service under the pseudonym Alice Dubois. This network provided important information to the British through occupied Belgium and the Netherlands. The network is estimated to have saved the lives of more than a thousand British soldiers during the 9 months of full operation from January to September 1915.

“The Alice Network” of a hundred people, mostly in forty kilometers of the front to the west and east of Lille, was so effective that she was nicknamed by her English superiors “the queen of spies.” She smuggled men to England, provided valuable information to the Intelligence Service, and prepared for her superiors in London a grid map of the region around Lille. When the German army installed a new battery of artillery, even camouflaged, this position was bombed by the Royal Flying Corps within eight days. Another opportunity allowed her to report the date and time of passage of the imperial train carrying the Kaiser on a secret visit to the front at Lille. During the approach to Lille, two British aircraft bombed the train and emerged, but missed their target. The German command did not understand the unique situation of these forty kilometers of “cursed” front (held by the British) out of nearly seven hundred miles of front. One of her last messages announced the preparation of a massive German attack on Verdun in early 1916. The information was relayed to the French commander who refused to believe it. Incredible!!! After all her success, this worthless French commander refused to believe her. Idiot!!

Louise was arrested by the Germans on October 20, 1915 near Tournai. On March 16, 1916, in Brussels, she was sentenced to forced labor for life. After being held for three years, she died on September 27, 1918 as a result of pleural abscesses poorly operated upon at Saint Mary’s Hospital in Cologne. Her body was repatriated on February 21, 1920. On March 16, 1920 a funeral was held in Lille in which she was posthumously awarded the Cross of the Legion of Honor, the Croix de guerre 1914-1918 with palm, and the British Military Medal, and she was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire. Her body is buried in the cemetery of Saint-Amand-les-Eaux.

It was 1914, and World War I was in the 5th month of a 51 month offensive. The war effort was in a bit of a transition period, following the stalemate of the Race to the Sea and the indecisive result of the First Battle of Ypres. As leadership on both sides reconsidered their strategies, hostilities entered a bit of a lull. The men were hoping for a break in the action for Christmas that year, but they had to wait for their orders. When the orders came down, it was not to be a Christmas truce, but rather a Christmas strike. As the first men to go forth prepared to make the first advances, some men were killed, and some returned. It was the way of war. The leadership wanted to take advantage of the possibility that the enemy might not expect a Christmas attack. One of the younger men…17 years old to be exact, couldn’t help himself. He began to sing Silent Night.His superiors ordered it to be quiet. They feared that the enemy was waiting in the darkness.

It was 1914, and World War I was in the 5th month of a 51 month offensive. The war effort was in a bit of a transition period, following the stalemate of the Race to the Sea and the indecisive result of the First Battle of Ypres. As leadership on both sides reconsidered their strategies, hostilities entered a bit of a lull. The men were hoping for a break in the action for Christmas that year, but they had to wait for their orders. When the orders came down, it was not to be a Christmas truce, but rather a Christmas strike. As the first men to go forth prepared to make the first advances, some men were killed, and some returned. It was the way of war. The leadership wanted to take advantage of the possibility that the enemy might not expect a Christmas attack. One of the younger men…17 years old to be exact, couldn’t help himself. He began to sing Silent Night.His superiors ordered it to be quiet. They feared that the enemy was waiting in the darkness.

Then, a miracle occurred. In the week leading up to the 25th of December, French, German, and British soldiers crossed trenches to exchange seasonal greetings…and to talk. In some areas, men from both sides ventured into what was called no man’s land, because to go there was to risk death. Nevertheless, on that Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, things seemed different. The soldiers took a chance and stepped forward, hoping to convince their enemies that they only wanted to bury their dead, and hoping that it would be  agreeable to stop the fighting for one hour to bury the dead. As they buried their dead, with heavy hearts, someone suggested that they take Christmas Day off. This was totally against their orders, and they knew that at some point they were going to have to go back and follow their orders. They were going to have to become enemies again. Still, for now…for this day, they mingled and exchange food and souvenirs. There were joint burial ceremonies and prisoner swaps. Men played games of football with one another, giving one of the most memorable images of the truce. Peaceful behavior was not ubiquitous, however, and fighting continued in some sectors, while in others the sides settled on little more than arrangements to recover bodies. Several meetings ended in carol-singing. Someone commented, “How many times in a life do you actually meet your enemy face to face.” It was almost strange to them, because these “enemies” were not the monsters they expected them to be. These were simply men, just like they were. I’m sure the men were in shock. it’s hard to have your total view of your enemy change so drastically and then have to follow your orders, pickup your weapons, and shoot at the same men again. The Christmas truce (German: Weihnachtsfrieden; French: Trêve de Noël) was a series of widespread but unofficial ceasefires along the Western Front of World War I around Christmas 1914.

agreeable to stop the fighting for one hour to bury the dead. As they buried their dead, with heavy hearts, someone suggested that they take Christmas Day off. This was totally against their orders, and they knew that at some point they were going to have to go back and follow their orders. They were going to have to become enemies again. Still, for now…for this day, they mingled and exchange food and souvenirs. There were joint burial ceremonies and prisoner swaps. Men played games of football with one another, giving one of the most memorable images of the truce. Peaceful behavior was not ubiquitous, however, and fighting continued in some sectors, while in others the sides settled on little more than arrangements to recover bodies. Several meetings ended in carol-singing. Someone commented, “How many times in a life do you actually meet your enemy face to face.” It was almost strange to them, because these “enemies” were not the monsters they expected them to be. These were simply men, just like they were. I’m sure the men were in shock. it’s hard to have your total view of your enemy change so drastically and then have to follow your orders, pickup your weapons, and shoot at the same men again. The Christmas truce (German: Weihnachtsfrieden; French: Trêve de Noël) was a series of widespread but unofficial ceasefires along the Western Front of World War I around Christmas 1914.

The Christmas Truces of 1914, while wonderful for the men, were not to be a Christmas tradition in World War I. The following year, a few units arranged ceasefires but the truces were not nearly as widespread as in 1914.  This was, in part, due to strongly worded orders from the high commands of both sides prohibiting truces. It was evident that while the mini-mutiny of 1914 was tolerated and the men were not punished, that this would not be tolerated in the future. It really didn’t matter, because the Soldiers were no longer amenable to truce by 1916. The war had become increasingly bitter after devastating human losses suffered during the battles of the Somme and Verdun, and the use of poison gas. While a Christmas truce would be nice in theory, bitter and angry feelings on both sides of a war make it an impractical idea. Still, in 1914, the miracle of the Christmas Truce was a wonderful treat for the men on all sides of a bitter war.

This was, in part, due to strongly worded orders from the high commands of both sides prohibiting truces. It was evident that while the mini-mutiny of 1914 was tolerated and the men were not punished, that this would not be tolerated in the future. It really didn’t matter, because the Soldiers were no longer amenable to truce by 1916. The war had become increasingly bitter after devastating human losses suffered during the battles of the Somme and Verdun, and the use of poison gas. While a Christmas truce would be nice in theory, bitter and angry feelings on both sides of a war make it an impractical idea. Still, in 1914, the miracle of the Christmas Truce was a wonderful treat for the men on all sides of a bitter war.

The other day, while reading an article about notable Native Americans, I came across a name that was familiar to me, but really didn’t seem like a Native American name. The name was Renville, the same name as my grand-nephew, James Renville. Immediately, I wondered if there might be a connection between Chief Gabriel Renville and my grand-nephew. The search didn’t take very long, before I had my answer. Gabriel Renville is my grand-nephew, James’ 1st cousin 7 times removed. I find that to be extremely amazing to think that James is related to an Indian chief. With that information, I wanted to fine out more abut this man.

The other day, while reading an article about notable Native Americans, I came across a name that was familiar to me, but really didn’t seem like a Native American name. The name was Renville, the same name as my grand-nephew, James Renville. Immediately, I wondered if there might be a connection between Chief Gabriel Renville and my grand-nephew. The search didn’t take very long, before I had my answer. Gabriel Renville is my grand-nephew, James’ 1st cousin 7 times removed. I find that to be extremely amazing to think that James is related to an Indian chief. With that information, I wanted to fine out more abut this man.

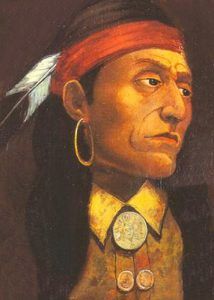

Chief Gabriel Renville was a mixed-blood Santee Sioux—his father was half French and his mother half-Scottish. He was born in April of 1825 at Big Stone Lake, South Dakota. Renville was the treaty chief of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Santee tribes and signed the 1867 treaty, which established the boundaries of the Lake Traverse Reservation. One source called him a Champion of Excellence.

He was careful to protect his people as much as he could, and was also instrumental in saving the lives of many white captives. During the 1862 Uprising, Renville opposed Little Crow and was influential in keeping many of the Santee out of the war. He lost a large amount of property, including horses appropriated by the hostile savages, or destroyed in consequence of his position to their murderous course. Renville served as chief of scouts for General Sibley during the campaign against the Sioux in 1863.

Even though Chief Renville was an ally of the whites, it didn’t help him when he settled on the reservation. The government agent there, Moses N. Adams, considered him hostile. Renville was the leader of the “scout party” which was in conflict with the “good church” Indians. I’m sure that was common in those days. Renville preserved many of the traditional Santee customs of polygamy and dancing, and he ignored Christianity, but he  was not opposed to economic progress and he and his followers became successful farmers on the reservation. However, the Sisseton agent favored the “church” Indians.

was not opposed to economic progress and he and his followers became successful farmers on the reservation. However, the Sisseton agent favored the “church” Indians.

Renville and other leaders of the traditional Indians accused Adams of discriminating against them in the disposition of supplies and equipment. He said Adams favored the idle church-goers instead of encouraging them to work….a situation not unlike the current welfare system. Agent Adams considered Renville a detriment and removed the chief form the reservation executive board which Adams had organized to carry out his policies. It was a move that was considered extreme. In 1874 Renville was finally successful in securing a government investigation of the Adam’s activities. The outcome of the investigation was an official censure of Adams. Chief Renville continued to practice the old Santee customs, yet he encouraged the Indians to farm. This progressive influence was greatly missed after his death in August 1892.

Through the years, people have been known to self destruct. Suicide is, unfortunately, not that uncommon, but this is not a story of suicide, spontaneous combustion, or accidental overdose. It is rather a story of an Army that “self destructed.” An entire army, although, some of them might have survived the “attack.” The insanity happened during the Austro-Turkish (Hapsburg-Ottoman) War, which lasted from 1787 to 1791, and occurred at almost the same time as the Russo-Turkish War was being fought, in which the Austrians were allies of Russia to fight a common foe. The Austrian (or Hapsburg Empire) Army at that time was composed of Austrians, Czechs, Germans, French, Serbs, Croats, and Polish, effectively making communication difficult, and a similar communications issue as the Tower of Babel, as possible. Most of the facts about the Austro-Turkish War were not written until 1831, when they were compiled in the Austrian Military Magazine. Another source was the German account by A. J. Gross-Hoffinger in Geschichte Josephs des Zweiten, which was itself not compiled until around 60 years later. Yet another, albeit less popular source, was the 1843 account of the war in “History of the Eighteenth Century and of the Nineteenth till the Overthrow of the French Empire, with particular reference to mental cultivation and progress.”

Through the years, people have been known to self destruct. Suicide is, unfortunately, not that uncommon, but this is not a story of suicide, spontaneous combustion, or accidental overdose. It is rather a story of an Army that “self destructed.” An entire army, although, some of them might have survived the “attack.” The insanity happened during the Austro-Turkish (Hapsburg-Ottoman) War, which lasted from 1787 to 1791, and occurred at almost the same time as the Russo-Turkish War was being fought, in which the Austrians were allies of Russia to fight a common foe. The Austrian (or Hapsburg Empire) Army at that time was composed of Austrians, Czechs, Germans, French, Serbs, Croats, and Polish, effectively making communication difficult, and a similar communications issue as the Tower of Babel, as possible. Most of the facts about the Austro-Turkish War were not written until 1831, when they were compiled in the Austrian Military Magazine. Another source was the German account by A. J. Gross-Hoffinger in Geschichte Josephs des Zweiten, which was itself not compiled until around 60 years later. Yet another, albeit less popular source, was the 1843 account of the war in “History of the Eighteenth Century and of the Nineteenth till the Overthrow of the French Empire, with particular reference to mental cultivation and progress.”

The “Battle of Karansebes,” apparently took place in the town of Karansebes, in present day Romania, on September 17th, 1788. Austria at that time was fighting with Turkey for control of the Danube River. The battle started with a number of Austrian cavalrymen soldiers on a night patrol. Looking for Turkish soldiers in the area where the Austrian Army had set up camp earlier that day, the Austrian Army night patrol chanced upon some Gypsies across the river. The Gypsies offered them Schnapps to relieve the war-weary soldiers. Seeing a chance to relax before the next day’s battle, the soldiers began drinking…their first mistake. Later, a contingent of Austrian infantry men found the cavalrymen having a party and wanted to join in. However, the cavalrymen refused them the alcohol…their second mistake, and the one that started a quarrel that turned into a fistfight. The next thing anybody knew, a shot was fired across the river. Some infantrymen in the distance shouted, “Turks, Turks,” mistaking the gunshot as coming from the enemy Ottoman Turks. Both parties, Austrian infantrymen and Austrian cavalrymen alike, fled back to the other side of the river where they camped, but by that time, chaos and disorder had taken over. Some soldiers were fleeing due to unpreparedness, while some German officers shouted, “Halt! Halt!.” Non-German soldiers not understanding the German language, and thought it meant “Allah”, referring to the Islamic Turkish making cries unto their God. This prompted the majority of the Austrian Army to start shooting at each other. Everyone commenced shooting at fellow Austrian and even shadows, thinking the enemy was upon them. Soon, an Austrian corps commander, thinking that a cavalry attack from the Turkish Army was in progress, ordered artillery fire on his own men!

The casualties were enormous, and amounted to about 10,000 Austrian soldiers dead and wounded. The Turkish Army arrived two days later, and found the town of Karansebes without defense. The Turkish Army took over the town easily soon after their arrival. Although many people attest that the battle really happened, some argue over its authenticity, due to the fact that no record of it was written until some 40 years later. Some argue that embarrassment may be the cause why no accounts of the incident were published until several decades later. Others say that the Austrian Army during that time was led by Austrian and German officers, while the infantrymen were composed of other European nation allies. In that regard, for some Austrians at least, if the battle fought was won, the victory was Austrian, but if they lost the battle, the blame was on the non-Austrian soldiers who had been forced into service.

Most people think that English came from England, and of course, it did, however, in England prior to the 19th century, the English language was not spoken by the aristocracy, but rather only by “commoners.” Back then, English used to belong to the people, and I suppose that might explain some of the “incorrect” uses of the language which have been so severely attacked by contemporary English speakers. Prior to the 19th century, the aristocracy in English courts spoke French. This was due to the Norman Invasion of 1066 and caused years of division between the “gentlemen” who had adopted the Anglo-Norman French and those who only spoke English. Even the famed King Richard the Lionheart was actually primarily referred to in French, as Richard “Coeur de Lion.”

Most people think that English came from England, and of course, it did, however, in England prior to the 19th century, the English language was not spoken by the aristocracy, but rather only by “commoners.” Back then, English used to belong to the people, and I suppose that might explain some of the “incorrect” uses of the language which have been so severely attacked by contemporary English speakers. Prior to the 19th century, the aristocracy in English courts spoke French. This was due to the Norman Invasion of 1066 and caused years of division between the “gentlemen” who had adopted the Anglo-Norman French and those who only spoke English. Even the famed King Richard the Lionheart was actually primarily referred to in French, as Richard “Coeur de Lion.”

In my opinion, this dual language society would have caused numerous problems. The indication I get is that neither side could speak the language of the other, but I don’t know how a monarchy could rule, if the “commoners” could not understand the language and therefore the orders of the monarchy. French was spoken and learned by anyone in the upper  classes. However, it became less useful as English lost its control of various places in France, where the peasants spoke French, too. After that…about, 1450…English was simply more useful for talking to anybody. It is still true that British royals and many nobles are fluent in French, but they only use it to talk to French people, just like everybody else.

classes. However, it became less useful as English lost its control of various places in France, where the peasants spoke French, too. After that…about, 1450…English was simply more useful for talking to anybody. It is still true that British royals and many nobles are fluent in French, but they only use it to talk to French people, just like everybody else.

To further confuse your preconceptions about the English language, the “British accent” was, in reality, created after the Revolutionary War, meaning contemporary Americans sound more like the colonists and British soldiers of the 18th century than contemporary Brits. Many people have made a point of how much they love the British accent, but I think very few people know the real story behind the British accent. In the 18th century and before, the British “accent” was the way we speak herein America. Of course, accents vary greatly  by region, as we have seen with the accents of the south and east in the United States, but the “BBC English” or public school English accent…which sounds like the James Bond movies…didn’t come about until the 19th century and was originally adopted by people who wanted to sound fancier. I suppose it was like the aristocracy and the commoners, in that one group didn’t want to be mistaken for the other. After being handily defeated by the American colonists, I’m sure that the British were looking for a way to seem superior, even in defeat. The change in the accent of the English language was sufficient to make that distinction. Maybe it was their way of saying that they were better than the American guerilla-type soldiers who beat them in combat…basically they might have lost, but they were superior…even if it was only in how they sounded.

by region, as we have seen with the accents of the south and east in the United States, but the “BBC English” or public school English accent…which sounds like the James Bond movies…didn’t come about until the 19th century and was originally adopted by people who wanted to sound fancier. I suppose it was like the aristocracy and the commoners, in that one group didn’t want to be mistaken for the other. After being handily defeated by the American colonists, I’m sure that the British were looking for a way to seem superior, even in defeat. The change in the accent of the English language was sufficient to make that distinction. Maybe it was their way of saying that they were better than the American guerilla-type soldiers who beat them in combat…basically they might have lost, but they were superior…even if it was only in how they sounded.

Sometimes, when a war plane is in danger of being captured by the enemy, the pilot might take measures to destroy it, so that the technological secrets don’t end up in enemy hands. In fact, I believe that these days, anytime a plane goes down in enemy territory, the pilots are told to destroy them, but I’m not sure on that.

Sometimes, when a war plane is in danger of being captured by the enemy, the pilot might take measures to destroy it, so that the technological secrets don’t end up in enemy hands. In fact, I believe that these days, anytime a plane goes down in enemy territory, the pilots are told to destroy them, but I’m not sure on that.

Strange as that may seem to most of us, on November 27, 1942, something even more strange happened, but I’m getting ahead of myself. In June of 1940, after the German invasion of France and the establishment of an unoccupied zone in the southeast, which was led by General Philippe Petain, Admiral Jean Darlan was committed to keeping the French fleet out of German control. At the same time, as a minister in the government that had signed an armistice with the Germans, one that promised a relative “autonomy” to Vichy France, Darlan was prohibited from sailing that fleet to British or neutral waters. It put him in a rather precarious position, to say the least.

The British were as concerned as the French. A German-commandeered fleet in southern France, so close to British-controlled regions in North Africa, could prove disastrous to the British, who decided to take matters into their own hands by launching Operation Catapult…the attempt by a British naval force to persuade the French naval commander at Oran to either break the armistice and sail the French fleet out of the Germans’ grasp…or to scuttle it. And if the French wouldn’t, the Brits would. If you’ve ever heard the expression, “between a rock and a hard place,” you can picture this situation. And the British tried to push their way in it. In a five-minute missile bombardment, they managed to sink one French cruiser and two old battleships. They also killed 1,250 French sailors. This would be the source of much bad blood between France and England throughout the war. General Petain broke off diplomatic relations with Great Britain.

Two years later, the situation had worsened, with the Germans now in Vichy and the armistice already violated. Admiral Jean de Laborde finished the job the British had started. Just as the Germans launched Operation Lila…

the attempt to commandeer the French fleet, at Toulon harbor, off the southern coast of France, Laborde ordered the sinking of 2 battle cruisers, 4 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers, 1 aircraft transport, 30 destroyers, and 16 submarines. Three French subs managed to escape the Germans and make it to Algiers, Allied territory. Only one sub fell into German hands. The marine equivalent of a scorched-earth policy had succeeded.

the attempt to commandeer the French fleet, at Toulon harbor, off the southern coast of France, Laborde ordered the sinking of 2 battle cruisers, 4 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers, 1 aircraft transport, 30 destroyers, and 16 submarines. Three French subs managed to escape the Germans and make it to Algiers, Allied territory. Only one sub fell into German hands. The marine equivalent of a scorched-earth policy had succeeded.