england

As an insurance agent, I have dealt with Lloyd’s of London many times. They were the company that could handle whatever needed to be handled, when no one else could. They were a no-nonsense company, and that always made me think of a traditional company…if not a stuffy old company filled with old men who almost look down on the people that end up needing insurance from them. Lloyd’s of London is an insurance and reinsurance market located in London, England. Unlike most of its competitors in the industry, it is not an insurance company. Lloyd’s is a corporate body governed by the Lloyd’s Act 1871 and subsequent Acts of Parliament. “Lloyd’s operates as a partially mutualized marketplace within which multiple financial backers, grouped in syndicates, come together to pool and spread risk.”

As an insurance agent, I have dealt with Lloyd’s of London many times. They were the company that could handle whatever needed to be handled, when no one else could. They were a no-nonsense company, and that always made me think of a traditional company…if not a stuffy old company filled with old men who almost look down on the people that end up needing insurance from them. Lloyd’s of London is an insurance and reinsurance market located in London, England. Unlike most of its competitors in the industry, it is not an insurance company. Lloyd’s is a corporate body governed by the Lloyd’s Act 1871 and subsequent Acts of Parliament. “Lloyd’s operates as a partially mutualized marketplace within which multiple financial backers, grouped in syndicates, come together to pool and spread risk.”

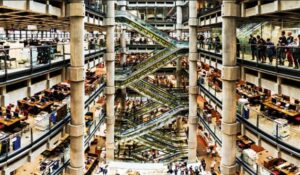

While Lloyd’s of London is a traditional company, the building that houses them is…a little strange. The Lloyd’s building, which is also known as the Inside-Out Building. It is located on the former site of East India House in Lime Street. That is in London’s main financial district, the City of London. The building is an example of radical Bowellism architecture in which the services for the building, such as ducts and elevators, are located on the exterior to maximize space in the interior. Whatever they were trying to accomplish, the result is a very strange building. The building is as unique inside as it is outside.

The building was completed in 1986, and in 2011, twenty-five years after its completion the building received Grade I Listing, which is “of exceptional interest and may also have been judged to be of significant national importance.” The Lloyd’s building is the youngest structure ever to obtain Grade I Listing. It is said by Historic England to be “universally recognized as one of the key buildings of the modern epoch.” However, its innovation

of having key service pipes and such routed outside the walls has led to very expensive maintenance costs due to their exposure to the elements. I suppose that makes sense, maybe more sense that the original structure of the building, which while interesting, may not be practical. In fact, Lloyd’s is actually considering a move to a more traditional building. That is almost sad, when you think about it.

of having key service pipes and such routed outside the walls has led to very expensive maintenance costs due to their exposure to the elements. I suppose that makes sense, maybe more sense that the original structure of the building, which while interesting, may not be practical. In fact, Lloyd’s is actually considering a move to a more traditional building. That is almost sad, when you think about it.

Since tobacco has been proven to cause cancer, its use has declined to a degree, leaving growers, producers, and warehouses in the wake. One such warehouse is The Tobacco Warehouse in Liverpool, England. With the decline of tobacco use, the warehouse became a ghost. Of course, it was a warehouse, and could have continued to be useful, but somehow, no one wanted to use it, and it slowly fell into disrepair. The logical solution would have been to tear it down, but since the site is considered a key landmark and World Heritage Site, it can’t be torn down. So, what now?

Since tobacco has been proven to cause cancer, its use has declined to a degree, leaving growers, producers, and warehouses in the wake. One such warehouse is The Tobacco Warehouse in Liverpool, England. With the decline of tobacco use, the warehouse became a ghost. Of course, it was a warehouse, and could have continued to be useful, but somehow, no one wanted to use it, and it slowly fell into disrepair. The logical solution would have been to tear it down, but since the site is considered a key landmark and World Heritage Site, it can’t be torn down. So, what now?

The Tobacco Warehouse was built in 1901, and the dream was to build the biggest warehouse the world had ever seen. It was to be a building fit for a  thriving city at the heart of global trade…Liverpool, England. They thought this was going to be a thriving business that would last a lifetime, but they didn’t plan on the fallout from the discovery that tobacco was linked to cancer. Suddenly everyone was quitting, or at least encouraged to do so, and the warehouse was used less and less…and finally not at all.

thriving city at the heart of global trade…Liverpool, England. They thought this was going to be a thriving business that would last a lifetime, but they didn’t plan on the fallout from the discovery that tobacco was linked to cancer. Suddenly everyone was quitting, or at least encouraged to do so, and the warehouse was used less and less…and finally not at all.

Operations at The Tobacco Warehouse stopped in the last portion of the 20th century, and its decline began then. So many old buildings, when they are no longer taken care of, begin to simply fall apart and become a danger to anyone who gets near them. The thing about The Tobacco Warehouse, was  that it wasn’t an ugly building, and it had some amazing views. It was right by the water. In fact, because it was a harbor warehouse, it had the uniqueness of the docks and the view over the water. The whole thing together seemed perfect to create an apartment complex. Of course, it would be something geared toward the young people, artists, and writers, but of course, anyone could rent there as well. They are actually called “hipster lofts.” So, the Tobacco Warehouse in Liverpool’s Stanley Dock could become the city’s newest residential hotspot, and all worthy of a Beatle! Most people wouldn’t really consider living in a warehouse, but the industrial look is very popular now, so this is a good fit.

that it wasn’t an ugly building, and it had some amazing views. It was right by the water. In fact, because it was a harbor warehouse, it had the uniqueness of the docks and the view over the water. The whole thing together seemed perfect to create an apartment complex. Of course, it would be something geared toward the young people, artists, and writers, but of course, anyone could rent there as well. They are actually called “hipster lofts.” So, the Tobacco Warehouse in Liverpool’s Stanley Dock could become the city’s newest residential hotspot, and all worthy of a Beatle! Most people wouldn’t really consider living in a warehouse, but the industrial look is very popular now, so this is a good fit.

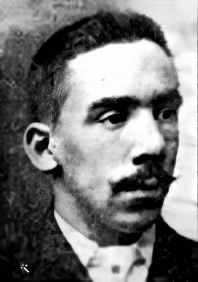

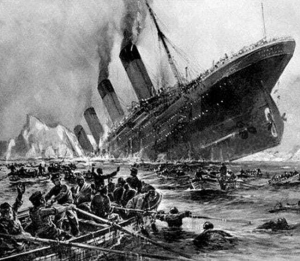

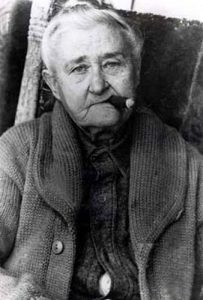

Charles Joughin had to figure that he was one of the most fortunate people on earth in 1912. Joughin was a British-American chef who had just landed a job as the chief baker on the greatest ship there was at the time…Titanic. Charles Joughin was born on Patten Street, next to the West Float in Birkenhead, England, on August 3, 1878. His parents were John Edwin (1846–1886)…a licensed victualer (a British person who is licensed to sell alcoholic liquor), and Ellen (Crombleholme) Joughin (1850–1938). He was enamored with the sea his whole young life, and he first went to sea in 1889 at age 11. He went on to become chief baker on various White Star Line steamships, notably the RMS Olympic, Titanic’s sister ship.

Charles Joughin had to figure that he was one of the most fortunate people on earth in 1912. Joughin was a British-American chef who had just landed a job as the chief baker on the greatest ship there was at the time…Titanic. Charles Joughin was born on Patten Street, next to the West Float in Birkenhead, England, on August 3, 1878. His parents were John Edwin (1846–1886)…a licensed victualer (a British person who is licensed to sell alcoholic liquor), and Ellen (Crombleholme) Joughin (1850–1938). He was enamored with the sea his whole young life, and he first went to sea in 1889 at age 11. He went on to become chief baker on various White Star Line steamships, notably the RMS Olympic, Titanic’s sister ship.

Joughin married Louise Woodward (born 11 July 1879), a native of Douglas, Isle of Man, on November 17, 1906, in Liverpool, England. They had a daughter, Agnes Lillian, in 1907, and a son, Roland Ernest, in 1909. It is believed that Louise died from complications in childbirth around 1919. Their new son, Richard, was also lost. It was a low point in his life.

As we all know, the job Joughin landed on the Titanic was going to prove to be a disaster. When the ship hit an iceberg on the evening of April 14th, at 11:40pm, Joughin was off duty. He was in his bunk when he felt the shock of the collision and immediately got up. He knew that this could not be good. Word was being passed down from the upper decks that officers were getting the lifeboats ready for launching. Joughin sent his thirteen men up to the boat deck with provisions for the lifeboats…four loaves of bread apiece, about forty pounds of bread. Joughin stayed behind for a time, but then followed them, reaching the Boat Deck at around 12:30am, he then helped with the evacuation.

Once on deck, Joughin joined Chief Officer Henry Tingle Wilde by Lifeboat 10. Joughin and the stewards and other seamen began helping the ladies and children through the crowd of people to the lifeboat. Sadly, many of the women were more afraid of the lifeboats than they were the sinking Titanic. They began to run away, saying that they were safer aboard the Titanic than in the tiny boats being tossed in the waves. Leaving him no choice, the Chief Baker then went on to A Deck and forcibly brought up women and children, throwing them into the lifeboat.

Joughin had been assigned as captain of Lifeboat 10, but he did not board the boat, because it was already being crewed by two sailors and a steward. After Lifeboat 10 was launched, Joughin went below, and “had a drop of liqueur” in his quarters, which was in reality a tumbler half-full of whiskey, as he later specified. Joughin was sure that he would not be one of the people allowed onboard a lifeboat, because there were simply not enough lifeboats to hold all the people onboard Titanic. After his drink, Joughin came upstairs again, after meeting “the old doctor,” assumedly William O’Loughlin. This was quite possibly the last time anyone ever saw  O’Loughlin. When Joughin arrived back at the Boat Deck, the rushing for boats had ended, because all the boats had been lowered. He then went down into the A Deck promenade and threw about fifty deck chairs overboard so that they could be used as flotation devices, by the unfortunate ones who could not get into a boat.

O’Loughlin. When Joughin arrived back at the Boat Deck, the rushing for boats had ended, because all the boats had been lowered. He then went down into the A Deck promenade and threw about fifty deck chairs overboard so that they could be used as flotation devices, by the unfortunate ones who could not get into a boat.

Joughin then went into the deck pantry on A Deck, for a drink of water. Suddenly, he heard a loud crash, “as if part of the ship had buckled” and indeed it had. He left the pantry and joined the crowd running aft toward the poop deck. As he was crossing the well deck, the ship suddenly gave a list over to port and, according to him, threw everyone in the well in a pile except for him. Joughin climbed to the starboard side of the poop deck, and hoisted himself over the safety rail, so that he was on the outside of the ship as it went down by the head. As the ship went down in a vertical position at 2:20am on April 15, 1912, Joughin rode it down as if it were an elevator, somehow managing not to get his head under the water. He said his head “may have been wetted, but no more.” So it was that Joughin was the last survivor to leave the Titanic. Now began his real ordeal.

Joughin testified that he kept paddling and treading water for about two hours. He also admitted to hardly feeling the cold, which he credited to the whiskey he drank. When daylight broke, he spotted the upturned Collapsible B lifeboat, with Second Officer Charles Lightoller and around 30 men standing on the side of the boat. Joughin slowly swam towards it, but there was no room for him. Cook Isaac Maynard, recognized him and held his hand as the Chief Baker held onto the side of the boat, with his feet and legs still in the water. A short time later, another lifeboat appeared and Joughin swam to it. He was taken in, where he stayed until he boarded the RMS Carpathia that had come to their rescue. Miraculously, he was rescued from the sea with only swollen feet. He survived the ship’s sinking, becoming notable for having survived in the frigid water for an exceptionally long time before being pulled onto the overturned Collapsible B lifeboat with virtually no ill effects. It is estimated that he was in the water for about four hours.

After surviving the Titanic disaster, Joughin returned to England, and was one of the crew members who reported to testify at the British Wreck Commissioner’s inquiry into the sinking headed by Lord Mersey. In 1920, Joughin moved permanently to the United States to Paterson, New Jersey. According to his obituary he was also on board the SS Oregon when it sank in Boston Harbor in 1886. He also served on American Export  Lines ships and on World War II troop transports before retiring in 1944.

Lines ships and on World War II troop transports before retiring in 1944.

After moving to New Jersey, he remarried to Mrs Annie Eleanor (Ripley) Howarth Coll (born December 29, 1870), a native of Leeds, who had first come to the USA in 1888. Annie was twice widowed twice and had a daughter named Rose, who was born in 1891. Annie’s death in 1943 was a great loss from which he never recovered. Twelve years later, Joughin was invited to describe his experiences in a chapter of Walter Lord’s book, A Night to Remember. Soon afterwards, his health rapidly declined. He died in a Paterson hospital on December 9, 1956, at the age of 78, after battling pneumonia for two weeks. He was buried by his wife in the Cedar Lawn Cemetery, in Paterson, New Jersey.

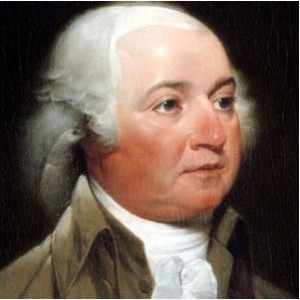

His Elective Majesty…sounds almost laughable, but it was almost the proper way to address the President of the United States, a fact that some presidents would probably have liked very much. Some presidents have tried to “rule” as a king would have, so they figure, why not buy in whole heartedly. One such president, who in fact made the original suggestion of title, was none other than, at the time, Vice President John Adams. The idea came from the fact that other heads of state are known by honorifics such as “His Excellency” and such, but United States presidents are only ever Mr President…or “sir” in a pinch. I’m sure that John Adams already had his sights set on becoming president at some point, and the second president of the United States seemed as good a time to run as any…or maybe he liked his own idea very much.

His Elective Majesty…sounds almost laughable, but it was almost the proper way to address the President of the United States, a fact that some presidents would probably have liked very much. Some presidents have tried to “rule” as a king would have, so they figure, why not buy in whole heartedly. One such president, who in fact made the original suggestion of title, was none other than, at the time, Vice President John Adams. The idea came from the fact that other heads of state are known by honorifics such as “His Excellency” and such, but United States presidents are only ever Mr President…or “sir” in a pinch. I’m sure that John Adams already had his sights set on becoming president at some point, and the second president of the United States seemed as good a time to run as any…or maybe he liked his own idea very much.

Apparently, thinking that the office of the President of the United States needed a title with more grandeur, Adams suggested that a president should be referred to as either “His Elective Majesty,” “His Mightiness,” or the slightly excessive “His Highness, the President of the United States of America and the Protector of their Liberties.” Just imagine any of those ideas. Every one of them make me giggle. Just take a moment to say (out loud) those titles in connection with the president…any president. With some presidents, any one of these titles is hilarious, and I’ll let you to decide to whom that statement applies, because these days we all have very specific opinions on the matter.

In those days, Washington was very aware of public fear about their newly won democracy slipping back into a  monarchy. They didn’t want this new nation to be too similar to England. They didn’t want this newly free nation to become once again ruled by a different kind of monarchy. So, they refused to allow the president to be titled as anything other than “The President of the United States.” They were right, of course, because the United States is not a “spin-off” of England…like England 2.0. The United States is a very unique nation…unlike any other, before her or after her. This nation was founded by people who refused to be told what to believe anymore. That is why they left England, where they were forced to live under a “state religion.” The nation was founded as “one nation, under God.” We would not have a king, because Jesus was our King of kings. We couldn’t give that title to a mere man.

monarchy. They didn’t want this new nation to be too similar to England. They didn’t want this newly free nation to become once again ruled by a different kind of monarchy. So, they refused to allow the president to be titled as anything other than “The President of the United States.” They were right, of course, because the United States is not a “spin-off” of England…like England 2.0. The United States is a very unique nation…unlike any other, before her or after her. This nation was founded by people who refused to be told what to believe anymore. That is why they left England, where they were forced to live under a “state religion.” The nation was founded as “one nation, under God.” We would not have a king, because Jesus was our King of kings. We couldn’t give that title to a mere man.

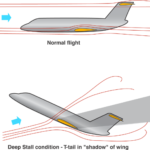

On June 18, 1972, a Trident jetliner in perfect condition, crashed into the outskirts of the town of Staines, Surrey, England, after takeoff from Heathrow Airport in London, killing 118 people. The crash became known as the Staines air disaster. How could this happen? There was nothing wrong with the airplane. It was not shot down. It was not a terrorist attack or a hijacking and the official cause of the accident remains unknown. Nevertheless, something happened. The aircraft went into a deep stall in the third minute of its flight and crashed to the ground, narrowly missing a busy main road. The public inquiry principally blamed the captain for failing to maintain airspeed and configure the high-lift devices correctly. It also cited the captain’s heart condition and the limited experience of the co-pilot, while noting an unspecified “technical problem” that the crew apparently resolved before take-off.

On June 18, 1972, a Trident jetliner in perfect condition, crashed into the outskirts of the town of Staines, Surrey, England, after takeoff from Heathrow Airport in London, killing 118 people. The crash became known as the Staines air disaster. How could this happen? There was nothing wrong with the airplane. It was not shot down. It was not a terrorist attack or a hijacking and the official cause of the accident remains unknown. Nevertheless, something happened. The aircraft went into a deep stall in the third minute of its flight and crashed to the ground, narrowly missing a busy main road. The public inquiry principally blamed the captain for failing to maintain airspeed and configure the high-lift devices correctly. It also cited the captain’s heart condition and the limited experience of the co-pilot, while noting an unspecified “technical problem” that the crew apparently resolved before take-off.

The summer of 1972 brought with it, serious problems facing the air-travel industry. Pilots were threatening to strike any day due to lack of security. Hijackings were becoming more common every day, and pilots were often the target of the attacks during a hijacking, so they were feeling particularly vulnerable. Nevertheless, none of the feared causes seemed to be the reason for the crash.

Everything was running smoothly that day at Heathrow Airport outside of London. British European Airways morning flight number 548 to Brussels was full and weather conditions were perfect. The Trident 1 jet took off with no incident, then just after its wheels retracted, it began simply falling from the sky. On impact the plane split and an intense fireball from the plane’s fully loaded fuel supply exploded, scattering the fuselage and passengers. Of the 118 passengers and crew members on board, only two were pulled from the wreckage alive. Both of these died a short time later.

After a thorough investigation failed to produce any clear reason for the crash, or any real reason at all, the investigators were left with speculation. The investigators’ best guess concerning the cause of the crash was that the jet was either carrying too much weight or that the weight was improperly distributed and the plane could not handle the stress. The only possible clue to the probable cause of the crash happened at 3:36pm, when flight dispatcher J Coleman presented the load sheet to Captain Stanley Key whose request for engine  start clearance was granted three minutes later. Then, as the doors were about to close, Coleman asked Key to accommodate a BEA flight crew that had to collect a Merchantman aircraft from Brussels. The request was granted, but the additional weight of the three crew members necessitated the removal of a quantity of mail and freight from the Trident to ensure its total weight (less fuel) did not exceed the permitted maximum of 91,998 pounds. This was exceeded by 53 pounds, but as there had been considerable fuel burn-off between startup and takeoff, the total aircraft weight (including fuel) was within the maximum permitted take-off weight. So they assumed that everything was fine. There is still no confirmation that overloading was the problem, but it is the only thing that was questionable, and whatever the cause, it cost 118 people their lives that day.

start clearance was granted three minutes later. Then, as the doors were about to close, Coleman asked Key to accommodate a BEA flight crew that had to collect a Merchantman aircraft from Brussels. The request was granted, but the additional weight of the three crew members necessitated the removal of a quantity of mail and freight from the Trident to ensure its total weight (less fuel) did not exceed the permitted maximum of 91,998 pounds. This was exceeded by 53 pounds, but as there had been considerable fuel burn-off between startup and takeoff, the total aircraft weight (including fuel) was within the maximum permitted take-off weight. So they assumed that everything was fine. There is still no confirmation that overloading was the problem, but it is the only thing that was questionable, and whatever the cause, it cost 118 people their lives that day.

These days, we have advance warnings about potentially dangerous storms heading our way. Of course, the meteorologists aren’t always right on with their predictions, but often they are incredibly accurate. In centuries gone by, it was often the elder men, the ones who had been around a while, who had watched the sky, to see the signs that would give them clues as to coming weather. Unfortunately, on November 14, 1703, any clues they might have seen would not do any good for the people of England. The unusual weather began that day with strong winds from the Atlantic Ocean that battered the southern part of Britain and Wales. The pounding winds damaged many homes and other buildings, but the hurricane-like storm only began doing serious damage on November 26. Then the winds estimated at over 80 miles per hour, blew bricks from some buildings and embedded them in others. Wood beams, separated from buildings, flew through the air and killed hundreds across the south of the country. Towns such as Plymouth, Hull, Cowes, Portsmouth, and Bristol were devastated.

These days, we have advance warnings about potentially dangerous storms heading our way. Of course, the meteorologists aren’t always right on with their predictions, but often they are incredibly accurate. In centuries gone by, it was often the elder men, the ones who had been around a while, who had watched the sky, to see the signs that would give them clues as to coming weather. Unfortunately, on November 14, 1703, any clues they might have seen would not do any good for the people of England. The unusual weather began that day with strong winds from the Atlantic Ocean that battered the southern part of Britain and Wales. The pounding winds damaged many homes and other buildings, but the hurricane-like storm only began doing serious damage on November 26. Then the winds estimated at over 80 miles per hour, blew bricks from some buildings and embedded them in others. Wood beams, separated from buildings, flew through the air and killed hundreds across the south of the country. Towns such as Plymouth, Hull, Cowes, Portsmouth, and Bristol were devastated.

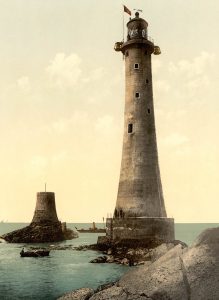

Finally, on November 27, 1703, the storm system finally dissipated over England. For almost two weeks, it had ripped the country nearly to shreds. With its hurricane force winds, the storm killed somewhere between 10,000 and 30,000 people. Hundreds of Royal Navy ships were lost to the storm, the worst in Britain’s history. It was the loss of the 300 Royal Navy ships that really caused the death toll to rise. The ships that were anchored carried some 8,000 sailors. All were lost. Then, the Eddystone Lighthouse, which had been built on a  rock outcropping 14 miles from Plymouth, was blown over by the storm. All of its residents, including its designer, Henry Winstanley, were killed. Huge waves on the Thames River sent water six feet higher than ever before recorded near London. More than 5,000 homes along the river were destroyed.

rock outcropping 14 miles from Plymouth, was blown over by the storm. All of its residents, including its designer, Henry Winstanley, were killed. Huge waves on the Thames River sent water six feet higher than ever before recorded near London. More than 5,000 homes along the river were destroyed.

The author Daniel Defoe, witnessed the storm, and it had such an impact on him that he wrote his first book, entitled “The Storm” the following year. In “The Storm” he described the storm as an “Army of Terror in its furious March.” Sometimes the best inspiration for writing a book is the events of real life. Defoe would later go on to write the well known novel “Robinson Crusoe.”

War is inevitable, it would seem. One nation does something another nation doesn’t like, and before you know it, one is attacking the other. War is a bloody business…most of the time. However, in the case of the war between the Netherlands and the Isles of Sicily, that isn’t what happened. The war was strange in every way, and even started in a strange way. The English Civil War, which was fought between the Royalists and Parliamentarians raged from 1642 to 1651. In that war, Oliver Cromwell, who was born into the middle gentry to a family descended from the sister of Henry VIII’s minister Thomas Cromwell, was instrumental in the outcome. He became an Independent Puritan after undergoing a religious conversion in the 1630s. Cromwell generally agreed with the many Protestant churches of that time period. He was an intensely religious man, and he fervently believed that God was guiding his victories. He was elected Member of Parliament for Huntingdon in 1628 and for Cambridge in the Short (1640) and Long (1640–1649) Parliaments. Cromwell had very specific political beliefs, and when he entered the English Civil Wars, it was on the side of the “Roundheads” or Parliamentarians, nicknamed “Old Ironsides.” He demonstrated his

War is inevitable, it would seem. One nation does something another nation doesn’t like, and before you know it, one is attacking the other. War is a bloody business…most of the time. However, in the case of the war between the Netherlands and the Isles of Sicily, that isn’t what happened. The war was strange in every way, and even started in a strange way. The English Civil War, which was fought between the Royalists and Parliamentarians raged from 1642 to 1651. In that war, Oliver Cromwell, who was born into the middle gentry to a family descended from the sister of Henry VIII’s minister Thomas Cromwell, was instrumental in the outcome. He became an Independent Puritan after undergoing a religious conversion in the 1630s. Cromwell generally agreed with the many Protestant churches of that time period. He was an intensely religious man, and he fervently believed that God was guiding his victories. He was elected Member of Parliament for Huntingdon in 1628 and for Cambridge in the Short (1640) and Long (1640–1649) Parliaments. Cromwell had very specific political beliefs, and when he entered the English Civil Wars, it was on the side of the “Roundheads” or Parliamentarians, nicknamed “Old Ironsides.” He demonstrated his  ability as a commander and was quickly promoted from leading a single cavalry troop to being one of the principal commanders of the New Model Army, playing an important role under General Sir Thomas Fairfax in the defeat of the Royalist or “Cavalier” forces.

ability as a commander and was quickly promoted from leading a single cavalry troop to being one of the principal commanders of the New Model Army, playing an important role under General Sir Thomas Fairfax in the defeat of the Royalist or “Cavalier” forces.

Cromwell fought the Royalists to the edges of the Kingdom of England. In the West of England this meant that Cornwall was the last Royalist stronghold. In 1648, Cromwell pushed on until mainland Cornwall was in the hands of the Parliamentarians. The Royalist Navy was forced to retreat to the Isles of Sicily, which lay off the Cornish coast and were under the ownership of Royalist John Granville. With the Royalists on the Isles of Sicily, and the Parliamentarians in England, the war ended…at least the English Civil War ended. Immediately thereafter…on March 30, 1651, one of history’s longest wars began, between the Netherlands and the Isles of Sicily. It lasted for 335 years and was filled with bitter hatred. Still, not a single person was killed. What kind of war is that? The war that comes closest to what this was, would be  the Cold War. It was called, The Three Hundred and Thirty Five Years’ War and many will dispute its existence. It is thought that the “war” ended long before it was officially listed as over, and that the only thing that wasn’t done was to sign a peace treaty, and that one thing extended the war for 335 years without a single shot being fired. That fact made it one of the world’s longest wars, and also a bloodless war. The big problem with the validity of the war was that there was no specific declaration of war. Because of that, no one knew if they needed to negotiate a peace treaty or not. Nevertheless, because they needed to end this war, and because the declaration of a state of war was not officially know to exist, peace was finally declared on April 17, 1987, bringing an end to any hypothetical war that may have been legally considered to exist.

the Cold War. It was called, The Three Hundred and Thirty Five Years’ War and many will dispute its existence. It is thought that the “war” ended long before it was officially listed as over, and that the only thing that wasn’t done was to sign a peace treaty, and that one thing extended the war for 335 years without a single shot being fired. That fact made it one of the world’s longest wars, and also a bloodless war. The big problem with the validity of the war was that there was no specific declaration of war. Because of that, no one knew if they needed to negotiate a peace treaty or not. Nevertheless, because they needed to end this war, and because the declaration of a state of war was not officially know to exist, peace was finally declared on April 17, 1987, bringing an end to any hypothetical war that may have been legally considered to exist.

In a war, the point is to kill the enemy, or be killed by the enemy. There is no room for soft hearts and compassion…or is there? On December 20, 1943, Charlie Brown, an American B-17 bomber pilot and his crew attempted to bomb an aircraft production facility in Bremen, Germany, as part of a bombing run with a squadron of B-17s. Unfortunately, the interior areas of Germany were better fortified with anti-aircraft guns. As the bombing run reached the factory, and dropped the payload, the 250 anti-aircraft guns which surrounded the factory were fired. Charlie Brown’s B-17, Ye Olde Pub, was hit, disabling two engines and forcing the plane out of formation. It was the habit of the German fighter planes to go after any stragglers, knowing that they were the weaker link. Brown’s damaged B-17 was chased down and several of the crew members were seriously wounded. The hit also knocked out all but one of the plane’s engines.

In a war, the point is to kill the enemy, or be killed by the enemy. There is no room for soft hearts and compassion…or is there? On December 20, 1943, Charlie Brown, an American B-17 bomber pilot and his crew attempted to bomb an aircraft production facility in Bremen, Germany, as part of a bombing run with a squadron of B-17s. Unfortunately, the interior areas of Germany were better fortified with anti-aircraft guns. As the bombing run reached the factory, and dropped the payload, the 250 anti-aircraft guns which surrounded the factory were fired. Charlie Brown’s B-17, Ye Olde Pub, was hit, disabling two engines and forcing the plane out of formation. It was the habit of the German fighter planes to go after any stragglers, knowing that they were the weaker link. Brown’s damaged B-17 was chased down and several of the crew members were seriously wounded. The hit also knocked out all but one of the plane’s engines.

Thinking the plane was doomed, the fighters turned their attention to other prey. Meanwhile, Ye Olde Pub tried to limp along toward England, hoping not to be spotted. Of course, they knew their hope of escape was quite unlikely, and before long they were spotted by German fighter pilot Franz Stigler, who was refueling. Stigler jumped into his plane and took off, catching up with the wounded plane quickly. Stigler was about to blast the plane, when he saw that the crew was seriously wounded. Stigler, a combat veteran with 22 confirmed kills, was reluctant to attack a defenseless aircraft, so instead pulled alongside the B-17 cockpit and signaled the crew to land. They refused. He then motioned in the direction of Sweden, which would get them on the ground, but also take them out of the war. It didn’t really matter, because the Allied crew didn’t understand.

Unable to convince them to land, but also unwilling to leave them, Stigler flew side-by-side with the stricken bomber, even though he was afraid his own plane might identify him, and his actions might get him executed. As Brown’s B-17 approached the safety of the English Channel, Stigler saluted and peeled off…not really expecting the B-17 to make it safely home. Miraculously, Brown kept the plane in the air and made it to England. Brown  often wondered why Stigler hadn’t shot him down, but never expected to know who the unknow German fighter pilot was. Nevertheless, after the war, Brown placed an ad in a World War II newsletter for pilot veterans. Amazingly, Stigler, who had relocated to Canada, saw the ad. The two pilots reunited, both still in shock to see the other, and when Brown ask the question that had been burning in his mind for years…why didn’t Stigler shoot them down? Stigler explained that to shoot at them would have been dishonorable. Charlie Brown was shocked to know that even among the enemy, there could exist such compassion. The two pilots immediately felt like they were forever connected. They remained close friends until their deaths in 2008.

often wondered why Stigler hadn’t shot him down, but never expected to know who the unknow German fighter pilot was. Nevertheless, after the war, Brown placed an ad in a World War II newsletter for pilot veterans. Amazingly, Stigler, who had relocated to Canada, saw the ad. The two pilots reunited, both still in shock to see the other, and when Brown ask the question that had been burning in his mind for years…why didn’t Stigler shoot them down? Stigler explained that to shoot at them would have been dishonorable. Charlie Brown was shocked to know that even among the enemy, there could exist such compassion. The two pilots immediately felt like they were forever connected. They remained close friends until their deaths in 2008.

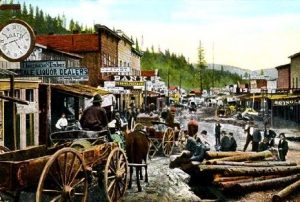

Alice Ivers Tubbs was born in Devonshire, England on February 17, 1851. She was the daughter of a conservative schoolmaster. While Alice was still a small girl, she moved with her family to the United States. The family first settled in Virginia, where Alice attended an elite boarding school for women. When she was a teenager, the family moved with the silver rush to Leadville, Colorado. As a young girl, Alice was raised to be a well-bred young lady, so few people would ever expect her to be known as “Poker Alice.” Nevertheless, marriage can change a person. While living in Leadville, Alice met a mining engineer named Frank Duffield, whom she married when she was just 20 years old. In the mining camps, gambling’s was quite common, and Frank was an enthusiastic player. He enjoyed visiting the gambling halls in Leadville and Alice naturally went along with him, rather than staying home alone. Alice stood quietly and watch her husband play…at first, but Alice was smart, and she picked up the game of poker easily. Soon she was sitting in on the games, and she was winning. Alice’s marriage to Frank Duffield was short-lived. Duffield, who worked in the mines as part of his job, was killed in an explosion. Needing to make a living, Alice, who was well educated, could have taught school, but even with 35,000 residents in Leadville, there was no school. There were also few jobs available for women, and those there were, did not appeal to Alice, so she decided to make a living gambling. Though Alice preferred the game of poker, she also learned to deal and play Faro. Very soon, she was in high demand…as a player and a dealer. Alice was a petite 5 foot 4 inch beauty, with blue eyes and thick brown hair. She was very rare in that she was a “lady” in a gambling hall…and not of the “soiled dove” variety. And Alice loved the latest fashions, she was a sight for the sore eyes of many a miner. Every time Alice had a big win, she began to take trips to New York City to buy the latest fashions.

Alice Ivers Tubbs was born in Devonshire, England on February 17, 1851. She was the daughter of a conservative schoolmaster. While Alice was still a small girl, she moved with her family to the United States. The family first settled in Virginia, where Alice attended an elite boarding school for women. When she was a teenager, the family moved with the silver rush to Leadville, Colorado. As a young girl, Alice was raised to be a well-bred young lady, so few people would ever expect her to be known as “Poker Alice.” Nevertheless, marriage can change a person. While living in Leadville, Alice met a mining engineer named Frank Duffield, whom she married when she was just 20 years old. In the mining camps, gambling’s was quite common, and Frank was an enthusiastic player. He enjoyed visiting the gambling halls in Leadville and Alice naturally went along with him, rather than staying home alone. Alice stood quietly and watch her husband play…at first, but Alice was smart, and she picked up the game of poker easily. Soon she was sitting in on the games, and she was winning. Alice’s marriage to Frank Duffield was short-lived. Duffield, who worked in the mines as part of his job, was killed in an explosion. Needing to make a living, Alice, who was well educated, could have taught school, but even with 35,000 residents in Leadville, there was no school. There were also few jobs available for women, and those there were, did not appeal to Alice, so she decided to make a living gambling. Though Alice preferred the game of poker, she also learned to deal and play Faro. Very soon, she was in high demand…as a player and a dealer. Alice was a petite 5 foot 4 inch beauty, with blue eyes and thick brown hair. She was very rare in that she was a “lady” in a gambling hall…and not of the “soiled dove” variety. And Alice loved the latest fashions, she was a sight for the sore eyes of many a miner. Every time Alice had a big win, she began to take trips to New York City to buy the latest fashions.

Due to her traveling from one mining camp to another to play poker, Alice soon acquired the nickname “Poker Alice.” In addition to playing the game, she often worked as a dealer, in cities all over Colorado including Alamosa, Central City, Georgetown, and Trinidad. Later on, Alice began to puff on large black cigars, still wearing her fashionable frilly dresses. She, nevertheless, never gambled on Sundays because of her religious beliefs. Alice carried a .38 revolver and wasn’t afraid to use it. It was rather a necessity, due to her lifestyle. Alice soon left Colorado and made her way to Silver City, New Mexico, where she broke the bank at the Gold Dust Gambling House, winning some $6,000. The win was followed by a trip to New York City, to replenish her wardrobe of fashionable clothing. Afterward, she returned to Creede, Colorado. She went to work as a dealer in Bob Ford’s saloon…the man who had earlier killed Jesse James. Alice later moved to Deadwood, South Dakota around 1890. In Deadwood, she met a man named Warren G. Tubbs, who worked as a housepainter in Sturgis, but sidelined as a dealer and  gambler. Alice usually beat Tubbs at poker, but that didn’t bother him. He was taken with her and they began to see each other socially. Once a drunken miner threatened Tubbs with a knife, Alice pulled out her .38 and put a bullet into the miner’s arm. I’m sure that man thought the threat was Tubbs, but the man should have watched Alice in stead. Later, the couple married and had seven children…four sons and three daughters. Because Tubbs was a painter by trade, he, along with Alice’s gambling profits, supported the family. The family moved out of Deadwood, to homesteaded a ranch near Sturgis on the Moreau River. Finally, Alice found something she loved more than gambling…for the most part. She helped with the ranch and raised her children. Then, fate would again deal Alice a bad hand. Tubbs was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Alice refused to leave his side. She planned to nurse him back to health. Tubbs lost his fight, and died of pneumonia in the winter of 1910. Alice was determined to give him a proper burial, so she loaded him into a horse-drawn wagon to take his body to Sturgis. It is thought that she had to pawn her wedding ring to pay for the funeral and afterward, went to a gambling parlor to earn the money to get her ring back.

gambler. Alice usually beat Tubbs at poker, but that didn’t bother him. He was taken with her and they began to see each other socially. Once a drunken miner threatened Tubbs with a knife, Alice pulled out her .38 and put a bullet into the miner’s arm. I’m sure that man thought the threat was Tubbs, but the man should have watched Alice in stead. Later, the couple married and had seven children…four sons and three daughters. Because Tubbs was a painter by trade, he, along with Alice’s gambling profits, supported the family. The family moved out of Deadwood, to homesteaded a ranch near Sturgis on the Moreau River. Finally, Alice found something she loved more than gambling…for the most part. She helped with the ranch and raised her children. Then, fate would again deal Alice a bad hand. Tubbs was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Alice refused to leave his side. She planned to nurse him back to health. Tubbs lost his fight, and died of pneumonia in the winter of 1910. Alice was determined to give him a proper burial, so she loaded him into a horse-drawn wagon to take his body to Sturgis. It is thought that she had to pawn her wedding ring to pay for the funeral and afterward, went to a gambling parlor to earn the money to get her ring back.

For Alice, the time spent on the ranch were some of the happiest days of her life and that during those years, she didn’t miss the saloons and gambling halls. Alice liked the peace and quiet of the ranch. Still, she had to make a living, so after Tubbs’ death, she hired a man named George Huckert to take care of the homestead, and she moved to Sturgis to earn her way. Huckert quickly fell in love with Alice and proposed marriage to her several times. Alice didn’t really love him, but finally married him, saying flippantly, “I owed him so much in back wages; I figured it would be cheaper to marry him than pay him off. So I did.” Once again, the marriage would be short. Alice was widowed once again when Huckert died in 1913.

During the Prohibition years, Alice opened a saloon called “Poker’s Palace” between Sturgis and Fort Meade that provided not only gambling and liquor, but also “women” who serviced the customers. One night, a drunken soldier began a fight in the saloon. He was destroying the furniture, and causing a ruckus. Alice pulled her .38 and shot the man. While in jail awaiting trial, she calmly smoked cigars and read the Bible. She was acquitted on grounds of self-defense, but her saloon had been shut down. Now, in her 70s and with her beauty and fashionable gowns long gone, Alice struggled in her last years. She continued to gamble, but these days, she dressed in men’s clothing. Once in a while, she was featured at  events like the Diamond Jubilee, in Omaha, Nebraska, as a true frontier character, where she was known to have said, “At my age, I suppose I should be knitting. But I would rather play poker with five or six ‘experts’ than eat.” She continued to run a “house” of ill-repute in Sturgis during her later years and was often arrested for drunkenness and keeping a disorderly house. Though she paid her fines, she continued to operate the business until she was finally arrested for repeated convictions of running a brothel and sentenced to prison. The governor took pity on Alice, who was then 75 years old, and pardoned her. At the age of 79, Alice underwent a gall bladder operation in Rapid City. Unfortunately, she died of complications on February 27, 1930. She was buried at Saint Aloysius Cemetery in Sturgis, South Dakota. In her lifetime, Alice claimed to have “won more than $250,000 at the gaming tables and never once cheated.” In fact, one of her favorite sayings was, “Praise the Lord and place your bets. I’ll take your money with no regrets.”

events like the Diamond Jubilee, in Omaha, Nebraska, as a true frontier character, where she was known to have said, “At my age, I suppose I should be knitting. But I would rather play poker with five or six ‘experts’ than eat.” She continued to run a “house” of ill-repute in Sturgis during her later years and was often arrested for drunkenness and keeping a disorderly house. Though she paid her fines, she continued to operate the business until she was finally arrested for repeated convictions of running a brothel and sentenced to prison. The governor took pity on Alice, who was then 75 years old, and pardoned her. At the age of 79, Alice underwent a gall bladder operation in Rapid City. Unfortunately, she died of complications on February 27, 1930. She was buried at Saint Aloysius Cemetery in Sturgis, South Dakota. In her lifetime, Alice claimed to have “won more than $250,000 at the gaming tables and never once cheated.” In fact, one of her favorite sayings was, “Praise the Lord and place your bets. I’ll take your money with no regrets.”

When we think of emergency personnel, we think of people who willingly put their lives on the line for others, and that is a good analogy, but while these people are passionate about their career, it is still a career. They expect, and need to be paid accordingly. Their job is dangerous, and they risk their lives every day, to go out and save other people. Unfortunately, they have to make a living too. For firefighters in England in 1977, the living they were making, wasn’t enough to support their families. So, as often happens, when the pay doesn’t equal the risk, the firefighters went on strike. They were demanding a 30% raise in pay.

When we think of emergency personnel, we think of people who willingly put their lives on the line for others, and that is a good analogy, but while these people are passionate about their career, it is still a career. They expect, and need to be paid accordingly. Their job is dangerous, and they risk their lives every day, to go out and save other people. Unfortunately, they have to make a living too. For firefighters in England in 1977, the living they were making, wasn’t enough to support their families. So, as often happens, when the pay doesn’t equal the risk, the firefighters went on strike. They were demanding a 30% raise in pay.

As the strike began, the 30,000 strong Fire Brigades Union claimed that 97.5% of its members had heeded the strike call and were no longer manning the pumps. It doesn’t take much imagination to realize that without firefighters, the cities were in serious trouble. Talks continued between union leaders and employers, but it didn’t look like there would be an early resolution, because the government insisted there was no breach of its 10% public sector pay ceiling.

As the situation became more critical, troops were brought in to provide emergency coverage of the cities. There was still concern among the soldiers about their lack of training and modern firefighting equipment. They would do their jobs, but that didn’t mean that they would know how to do it well. The reality is that firefighting is a highly skilled job, in which the people are trained, and they know the risks.

The firefighters said that they had already waited two years for the Government to consider their pay claim…and they were done waiting. During that two years, the police department had received a substantial pay rise while firefighters, in line with many others, had to settle for £6 per week. Much of the discussion between the union and employers is focused on the possibility of a reduction in the 48-hour working week, which would allow officers to earn considerable overtime payments.

In many areas firefighters have deserted their stations only reluctantly. Firemen, still wearing their uniforms and pickets armbands, rushed to the scene of a fire at St Andrew’s Hospital in Bow, East London, after a basement storeroom caught light. One of the officers said: “We couldn’t let them die.” And, “It was a hospital, what else could we do but come and help?” A colleague Barry Holmes said: “The situation here was really dangerous and people could have died if we had not come.” Emergency troops arrived at the scene first, and fire officers said afterwards that without their help the building would have burned to the ground.

“Elsewhere in the country, troops averted a major catastrophe on Merseyside when they stopped a haulage depot blaze at Kirkdale spreading to a 500 gallon gasoline storage tank. A woman and her twin sons escaped from a bungalow at Wallington in Surrey after a gas container exploded starting a fire. Troops in a Green Goddess had to drive 25 minutes from Croydon and the house was destroyed. The local fire station was less than three minutes drive away.” The striking firefighters received no strike pay, but got donations from the  public as Christmas approached. The insurance companies picked up the final bill for the dispute with payouts totaling £117.5m compared with £52.3m for the same three months the previous year. The firefighters eventually settled for a 10% increase, taking an average salary to just over £4,000, with the promise of more to come.

public as Christmas approached. The insurance companies picked up the final bill for the dispute with payouts totaling £117.5m compared with £52.3m for the same three months the previous year. The firefighters eventually settled for a 10% increase, taking an average salary to just over £4,000, with the promise of more to come.

Firefighters went on strike again in 2002/2003, in a long-running dispute which included a series of one day strikes over a period of several months. They finally ended with a 16% pay raise that was tied to a modernization package. The Fire Brigades Union chief, Andy Gilchrist said at the time of the settlement it was “a first phase” towards raising a fire officer’s basic pay to £30,000. I say, it was about time.