eiffel tower

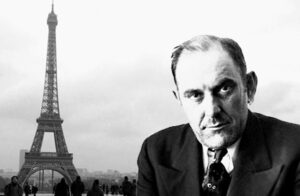

You’ve heard of con artists selling things like the London Bridge or some ocean front property in Arizona. Well, Victor Lustig was one of the best con artists ever. Lustig was born in Hostinné, Bohemia, Austria-Hungary on January 4, 1890. He was a smart young man, who learned new things easily, but that could be said to have also contributed to his. When a student doesn’t have to spend a lot of time studying, they can become bored and look for entertainment outside of their studies. When Lustig was 19, while taking a break from his studies in Paris, Lustig took to gambling and womanizing, It was during this time he received a defining scar on the left side of his face from the jealous boyfriend of a woman was having an affair with. When he left school, Lustig decided that he could make his best living, using his quick wit and ability to size up of a situation, as well as his fluency in several languages to embark on a life of crime. Like all criminals, the idea of easy money, along with a big helping of excitement, drew Lustig in. He focused on a variety of scams and cons that provided him with property and money, and before long he was a professional con man.

You’ve heard of con artists selling things like the London Bridge or some ocean front property in Arizona. Well, Victor Lustig was one of the best con artists ever. Lustig was born in Hostinné, Bohemia, Austria-Hungary on January 4, 1890. He was a smart young man, who learned new things easily, but that could be said to have also contributed to his. When a student doesn’t have to spend a lot of time studying, they can become bored and look for entertainment outside of their studies. When Lustig was 19, while taking a break from his studies in Paris, Lustig took to gambling and womanizing, It was during this time he received a defining scar on the left side of his face from the jealous boyfriend of a woman was having an affair with. When he left school, Lustig decided that he could make his best living, using his quick wit and ability to size up of a situation, as well as his fluency in several languages to embark on a life of crime. Like all criminals, the idea of easy money, along with a big helping of excitement, drew Lustig in. He focused on a variety of scams and cons that provided him with property and money, and before long he was a professional con man.

Lustig decided that he might like to try traveling along with his scams, and many of his initial cons were committed on ocean liners sailing between the Atlantic ports of France and New York City. He deduced that rich travelers didn’t need their money as badly as he did, so they became a prime target. One of his favorite schemes was one in which he posed as a musical producer who sought investment in a non-existent Broadway production. The scheme worked well in that the victim wouldn’t expect an immediate return on the investment, and by the time they realized that it had been a con, Lustig was long gone. Lustig’s travel schemes came to an end when trips on trans-Atlantic liners were suspended in the wake of World War I, Lustig had to find a new territory in which to run his schemes. So, Lustig opted for a trip to the United States. It seemed like the best option, because he was becoming a little too well known amongst various law enforcement agencies for the scams he committed, including one he conducted in 1922 in which he conned a bank into giving him money for a portion of bonds he was offering for a repossessed property, only to use sleight of hand to escape with both the money and the bonds.

By 1925, Lustig had traveled back to France. While reading the local newspaper in Paris, he came across an article discussing the problems faced with maintaining the Eiffel Tower. Instantly, he knew that he has his next con. At the time, the monument had begun to fall into disrepair, and the city was finding it increasingly expensive to maintain and repaint it. Incredibly, the article speculated that the public opinion might be to simply remove it. It was this part of the article that really inspired Lustig to use the Eiffel Tower as part of his next con. He quickly researched the information he would need to make his scam believable and set to work  preparing the scam, which included hiring a forger to produce fake government stationery for him.

preparing the scam, which included hiring a forger to produce fake government stationery for him.

The scam was carried out on a small group of scrap metal dealers, who were invited to a confidential meeting at an expensive hotel. Lustig identified himself to them as the Deputy Director-General of the Ministère de Postes et Télégraphes (Ministry of Posts and Telegraphs). During the meeting, Lustig convinced the men that the upkeep of the Eiffel Tower was becoming too much for Paris and that the French government wished to sell it for scrap, but that because such a deal would be controversial and likely spark public outcry, nothing could be disclosed until all the details were thought out. Lustig Told the men that he had been charged with the task of selecting the dealer who would receive ownership of the structure. The men were told that they had “made the final cut” of possible contract winners, because of their reputations as “honest businessmen” and that he was going to make a final selection after the meeting. His speech included genuine insight about the monument’s place in the city and how it did not fit in with the city’s other great monuments like the Gothic cathedrals or the Arc de Triomphe. The men were convinced that Lustig was legitimate.

Because of his long history of reading people, Lustig knew how a perfect mark would look and act, and before long, he had his choice…André Poisson, who was an insecure man who wished to rise up amongst the inner circles of the Parisian business community. As Poisson showed the keenest interest in purchasing the monument, Lustig decided to focus on him once the dealers sent their bids to him. He then arranged a private meeting with Poisson, at which Lustig convinced him that he was a corrupt official, claiming that his government position did not give him a generous salary for the lifestyle he wished to enjoy. Poisson became concerned that he would not win the bid, so he agreed to pay a large bribe to secure ownership of the Eiffel Tower. His lust for the position of “top businessman” would be his downfall. Once Lustig received his bribe and the funds for the monument’s “sale” (around 70,000 francs, which is about $78,757), he soon fled to Austria. Lustig correctly suspected that when Poisson found out he had been conned, he would be too ashamed and embarrassed to inform the French police of what he had been caught up in. Still, he bided his time, checking the newspapers just to be sure. When his suspicions proved correct…when he could find no reference of his con within their pages, he returned to Paris later that year to pull off the same scheme one more time. The second attempt didn’t go over so well. Someone informed the police about the scam and Lustig had no choice but to flee to United States to evade arrest. Lustig is widely regarded as one of the most notorious con artists of his time, and he is infamous for being “the man who sold the Eiffel Tower twice.”

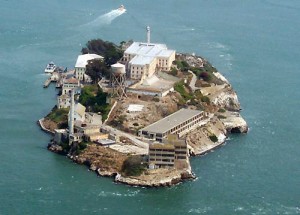

Lustig was finally arrested on May 10, 1935, in New York. He was charged with counterfeiting. He managed to escape from the Federal House of Detention in New York City by faking illness and using a specially made rope to climb out of the building on the day before his trial, but he was recaptured 27 days later in Pittsburgh. Lustig pleaded guilty at his trial and was sentenced to fifteen years in prison on Alcatraz Island, California for his original charge, with a further five years for his prison escape. On March 9, 1947, Lustig contracted pneumonia and died two days later at the Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield, Missouri. On his death certificate his occupation was listed as apprentice salesman…and I guess he was at that.

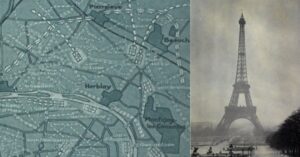

When you have a landmark city…a City of Lights, you want to protect it from the ravages of war. Paris was just that…the City of Lights, and during World War I, in an effort to protect the city from enemy bombs, the French built a “fake Paris” to the city’s immediate north. Complete with a duplicate Champs-Elysées and Gard Du Nord, this “dummy version” of Paris was built by the French towards the end of the war as a means of throwing off German bomber and fighter pilots flying over French skies. Wily military strategists, understandably tired of the enemy dropping bombs on their beautiful hometown, had decided that the best way to keep the city safe was to bring in a stunt double…a life-sized mock up situated to act as a decoy to draw fire from Paris proper.

When you have a landmark city…a City of Lights, you want to protect it from the ravages of war. Paris was just that…the City of Lights, and during World War I, in an effort to protect the city from enemy bombs, the French built a “fake Paris” to the city’s immediate north. Complete with a duplicate Champs-Elysées and Gard Du Nord, this “dummy version” of Paris was built by the French towards the end of the war as a means of throwing off German bomber and fighter pilots flying over French skies. Wily military strategists, understandably tired of the enemy dropping bombs on their beautiful hometown, had decided that the best way to keep the city safe was to bring in a stunt double…a life-sized mock up situated to act as a decoy to draw fire from Paris proper.

London’s Daily Telegraph explains that the fake city wasn’t just “a bunch of cardboard cutouts.” No, far from it, in fact. There were “electric lights, replica buildings, and even a copy of the Gare du Nord—the station from which high-speed trains now travel to and from London.” The painters went so far as to use paint to create “the impression of dirty glass roofs of factories.” Fake trains and railroad tracks were lit up as well. There was a phony Champs-Elysées. Many of us today would say, “How could that work? The Germans must have known where they were dropping their bombs!” Nevertheless, it stands to reason that in the early 20th century, the plan could have worked. “Radar was in its infancy in 1918, and the long-range Gotha heavy bombers being used by the German Imperial Air Force were similarly primitive,” the Telegraph notes. “Their crew would hold bombs by the fins and then drop them on any target they could see during quick sorties over major cities like Paris and London.”

No one really knows how well the plan might have worked, because it was never put to the test. World War I ended before the fake city was finished. Both the real Paris and the fake one escaped significant damage. The fake version has long since been dismantled, though photos of it still remain. I suppose it was a ghost town of  it’s own, and had it remained, it would have been interesting to visit and very likely a tourist attraction. Seriously…the idea of a to-scale decoy city made of wood and canvas dumped out in the leafy suburbs just a few miles from Paris’ instantly recognizable landscape may seem a little far fetched, if not completely crazy. Nevertheless, as the war progressed and French anti-aircraft technology improved, the daylight airship bombings which had previously caused such havoc were eventually rendered too risky for the planes. As such, any bombing raids were forced to take place under cover of darkness and it was at this point that an illuminated sham Paris began to…shall we say…shine!!

it’s own, and had it remained, it would have been interesting to visit and very likely a tourist attraction. Seriously…the idea of a to-scale decoy city made of wood and canvas dumped out in the leafy suburbs just a few miles from Paris’ instantly recognizable landscape may seem a little far fetched, if not completely crazy. Nevertheless, as the war progressed and French anti-aircraft technology improved, the daylight airship bombings which had previously caused such havoc were eventually rendered too risky for the planes. As such, any bombing raids were forced to take place under cover of darkness and it was at this point that an illuminated sham Paris began to…shall we say…shine!!

To further validate the idea, French fighter pilots reported that during night flights they looked for familiar features of the landscape below when attempting to locate Paris. According to their research, railways, lakes, rivers, roads and woodland were the most useful indicators that they were in the neighborhood. Using this information, the mastermind behind the replica project, Fernand Jacopozzi, along with his team of highly capable engineers worked to make life even harder for the German pilots who were already struggling to find their bearings in an era before radar or precision targeting. Intending to confuse an enemy pilot sufficiently that he would start to doubt his own bearings, the construction of Paris’ mirror image began in earnest at Villepinte to the northeast where a working model of the Gare de l’Est gradually began to take form.

The “fake Paris” was exquisite. No detail was overlooked: “complex, sprawling networks of lights arranged skillfully creating the impression of railway tracks and avenues, as well as storm lamps clustered together on ingenious moving platforms designed to simulate vast steam trains in motion. Immense empty sheds masquerading as factories had translucent sheets of painted canvas stretched tightly across their wooden frames which were illuminated from underneath, an arrangement that to anyone passing overhead would look remarkably like the dirty glass roofs characteristic of industrial buildings. Working furnaces were also installed to add an extra dimension of reality and the factory’s lights were even configured to dim noticeably during an air raid, fooling enemy pilots into believing that the facsimile buildings were, in fact, occupied.”

Because World War I ended, it was only this small part of Zone A that was built. The German bombing campaign came to an end in September 1918 and the armistice was signed at Compiègne two months later. The mock factories and railway network at Villepinte were dismantled shortly after the hostilities ceased. By the beginning of the 1920s little remained of the project. Though his fascinating idea never really got much further than the drawing board, the designs of Fernand Jacopozzi inspired similarly ambitious plans in the United States during World War II.

When we think of Paris, the first thing that comes to mind is the Eiffel Tower. If history had been different, those of us alive today would most likely be completely unaware of the historical icon. The Eiffel Tower was built in 1889, and since that time, over 200,000,000 people have visited it, which makes the Eiffel Tower the most visited monument in the world. The Eiffel Tower was erected for the Paris Exposition, and was inaugurated by the Prince of Wales, who went on to become King Edward VII. The tower was the entrance arch to exposition, and was the most visited site during the Exposition. As they were preparing for the Exposition, seven hundred proposals were submitted in a design competition. In the end, it was the radical design of French engineer Alexandre Gustave Eiffel that was unanimously chosen. Eiffel was assisted in the design by two engineers, Maurice Koechlin and Emile Nougier, and architect Stephen Sauvestre.

When we think of Paris, the first thing that comes to mind is the Eiffel Tower. If history had been different, those of us alive today would most likely be completely unaware of the historical icon. The Eiffel Tower was built in 1889, and since that time, over 200,000,000 people have visited it, which makes the Eiffel Tower the most visited monument in the world. The Eiffel Tower was erected for the Paris Exposition, and was inaugurated by the Prince of Wales, who went on to become King Edward VII. The tower was the entrance arch to exposition, and was the most visited site during the Exposition. As they were preparing for the Exposition, seven hundred proposals were submitted in a design competition. In the end, it was the radical design of French engineer Alexandre Gustave Eiffel that was unanimously chosen. Eiffel was assisted in the design by two engineers, Maurice Koechlin and Emile Nougier, and architect Stephen Sauvestre.

Believe it or not, there was some controversy over the winning design. The Paris city government actually received a petition, signed by about 300 people in a effort to prevent the city government from constructing the tower. Some famous personalities like Guy de Maupassant, Emile Zola, and Charles Garnier also signed the petition. They felt that the Eiffel Tower would be useless and monstrous, and it endangered French art and history. Wow!! Today, they would be stunned at the beauty it posses, especially when it is lit up at night.

Of course, the tower was ultimately built and it was given out for a 20-year lease. When the lease expired in 1909, it was planned to tear down the iconic tower. In the end, it was its antenna that saved the tower, as it was used for telegraphy. The tower also played an important role in capturing the infamous spy Mata Hari

during World War I. Following these events, the tower gained acceptance among the French. As 1910 arrived, the Eiffel Tower became a part of the International Time Service and the French Radio has been using the tower since 1918. The French Television started using the height of the tower from 1957. I don’t really know if most of us knew about all the other uses for the Eiffel Tower, other than the tourist attraction most of us connect with it.

during World War I. Following these events, the tower gained acceptance among the French. As 1910 arrived, the Eiffel Tower became a part of the International Time Service and the French Radio has been using the tower since 1918. The French Television started using the height of the tower from 1957. I don’t really know if most of us knew about all the other uses for the Eiffel Tower, other than the tourist attraction most of us connect with it.

Today this fantastic structure of iron and rivets is iconic symbol of Paris and people from all over the world come to Paris just to marvel at this man-made wonder. The stunning photographs that have been taken from all angles, and the romantic appeal for so many couples of all ages and nationalities have worked together to make the Eiffel Tower famous.