czar nicholas ii

How can the February Revolution begin on March 8th, you might ask? Well, if you know much about 1917 Russia, you know that the calendar at that time was the Julian calendar, and not the Gregorian calendar that we use today in most countries. That was how the February Revolution (known as such because of Russia’s use of the Julian calendar) which began on February 23rd in the Julian calendar, actually began on March 8th in the now-used Gregorian calendar. The February Revolution started with riots and strikes over the scarcity of food erupt in Petrograd. One week later, centuries of czarist rule in Russia ended with the abdication of Czar Nicholas II, and Russia took a dramatic step closer to a communist revolution.

How can the February Revolution begin on March 8th, you might ask? Well, if you know much about 1917 Russia, you know that the calendar at that time was the Julian calendar, and not the Gregorian calendar that we use today in most countries. That was how the February Revolution (known as such because of Russia’s use of the Julian calendar) which began on February 23rd in the Julian calendar, actually began on March 8th in the now-used Gregorian calendar. The February Revolution started with riots and strikes over the scarcity of food erupt in Petrograd. One week later, centuries of czarist rule in Russia ended with the abdication of Czar Nicholas II, and Russia took a dramatic step closer to a communist revolution.

By 1917, Czar Nicholas II had already lost all of his credibility. The corruption in the government was rampant, the economy was a mess, and Nicholas repeatedly dissolved the Duma…the Russian parliament established after the Revolution of 1905…whenever it opposed his will. All that was bad, but the immediate cause of the February Revolution, which was the first phase of the Russian Revolution of 1917…was Russia’s disastrous involvement in World War I. Militarily, Russia was no match for industrialized Germany, and Russian casualties were greater than those sustained by any nation in any previous war. They were severely pounded by the Germans. Meanwhile, the economy was hopelessly disrupted by the costly war effort, and moderates joined Russian radical elements in calling for the overthrow of the czar, who was already weak due to family problems, namely a sick child.

While most of the world switched from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar in 1582, Russia didn’t make the conversion until 1918. So, 104 years ago, the Russian people irrevocably had half a month wiped out of their lives…13 days of February in 1918. Their calendar went from January 31, 1918, to February 14, 1918…overnight. On March 8th or February 23rd, 1917, depending on the calendar you choose to use for the event, demonstrators were clamoring for bread in the streets of the Russian capital of Petrograd (now known as Saint Petersburg). Supported by 90,000 men and women on strike, the protesters clashed with police but refused to leave the streets. The strike spread, and on March 10th, it had spread among all of Petrograd’s workers, and irate mobs of workers destroyed police stations. Several factories elected deputies to the Petrograd Soviet, or “council” of workers’ committees, following the model devised during the Revolution of 1905.

By March 11th, the troops of the Petrograd army garrison ordered soldiers to crush the uprising. Regiments opened fire, killing demonstrators, but the protesters kept to the streets, and the troops began to waver. Nicholas dissolved the Duma again on that day, and on March 12, the revolution triumphed when regiment after regiment of the Petrograd garrison defected to the cause of the demonstrators. The soldiers, some 150,000 men, subsequently formed committees that elected deputies to the Petrograd Soviet.

The uprising forced the imperial government to resign, and the Duma formed a provisional government that peacefully vied with the Petrograd Soviet for control of the revolution. March 14th, saw the Petrograd Soviet  issuing “Order No. 1,” which instructed Russian soldiers and sailors to obey only those orders that did not conflict with the directives of the Soviet. Czar Nicholas II abdicated the throne the next day, March 15th, in favor of his brother Michael, who refused the crown, ending the czarist autocracy.

issuing “Order No. 1,” which instructed Russian soldiers and sailors to obey only those orders that did not conflict with the directives of the Soviet. Czar Nicholas II abdicated the throne the next day, March 15th, in favor of his brother Michael, who refused the crown, ending the czarist autocracy.

The Petrograd Soviet tolerated the new provincial government and hoped to salvage the Russian war effort while ending the food shortage and many other domestic crises…a daunting task. Meanwhile, Vladimir Lenin, leader of the Bolshevik revolutionary party, left his exile in Switzerland and crossed German enemy lines to return home and take control of the Russian Revolution.

Czar Nicholas II and Czarina Alexandra were not always considered popular, in fact you could say that the tumultuous reign of Nicholas II, who was the last czar of Russia, was tarnished by his ineptitude in both foreign and domestic affairs that helped to bring about the Russian Revolution. Nevertheless, he was a part of the Romanov Dynasty, which had ruled Russia for three centuries.

Czar Nicholas II and Czarina Alexandra were not always considered popular, in fact you could say that the tumultuous reign of Nicholas II, who was the last czar of Russia, was tarnished by his ineptitude in both foreign and domestic affairs that helped to bring about the Russian Revolution. Nevertheless, he was a part of the Romanov Dynasty, which had ruled Russia for three centuries.

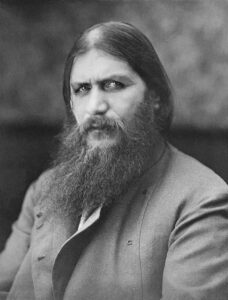

I think that his young son, Alexi’s health issues played a rather large part in what many would consider his failure to lead, but things were looking up for the family when a young Siberian-born muzhik, or peasant, who underwent a religious conversion as a teenager and proclaimed himself a healer with the ability to predict the future, won the favor of Czar Nicholas II and Czarina Alexandra. Grigory Efimovich Rasputin was able, through his ability, to stop the bleeding of their hemophiliac son, Alexei, in 1908.

Many people, from that time forward, began to criticize Rasputin for his lechery and drunkenness, if these things are true. The left-wing Bolsheviks were deeply unhappy with the government and began spreading calls for a military uprising. The Bolsheviks were a revolutionary party, dedicated to Karl Marx’s ideas, and they wanted a coup d’etat, which is a sudden, violent, and unlawful seizure of power from a government. That said, the last thing they needed was a “miracle-working holy man” advising the Czar. Rasputin exerted a powerful influence on the ruling family of Russia, infuriating nobles, church orthodoxy, and peasants alike. He particularly influenced the czarina and was rumored to be her lover.

Rasputin had to go, so sometime over the course of the night and the early morning of December 29-30, 1916, Grigory Efimovich Rasputin was murdered by Russian nobles eager to end his influence over the royal family.  Still, that wasn’t all, and the rest of it should have scared them…to death. A group of nobles, led by Prince Felix Youssupov, the husband of the czar’s niece, and Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, Nicholas’s first cousin, lured Rasputin to Youssupov Palace on the night of December 29, 1916. First, Rasputin’s would-be killers first gave the monk food and wine laced with cyanide…which miraculously had no effect on him. When he failed to react to the poison, they shot him at close range, leaving him for dead. Once again, they failed to kill him. Rasputin revived a short time later and attempted to escape from the palace grounds. They caught up with him and shot him again, and then beat him viciously. Finally, because Rasputin was still alive, they bound him and tossed him into a freezing river. His body was discovered several days later and the two main conspirators, Youssupov and Pavlovich were exiled. It was the beginning of the end. The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 put an end to the imperial regime. Nicholas and Alexandra were murdered, and the long, dark reign of the Romanovs was over.

Still, that wasn’t all, and the rest of it should have scared them…to death. A group of nobles, led by Prince Felix Youssupov, the husband of the czar’s niece, and Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, Nicholas’s first cousin, lured Rasputin to Youssupov Palace on the night of December 29, 1916. First, Rasputin’s would-be killers first gave the monk food and wine laced with cyanide…which miraculously had no effect on him. When he failed to react to the poison, they shot him at close range, leaving him for dead. Once again, they failed to kill him. Rasputin revived a short time later and attempted to escape from the palace grounds. They caught up with him and shot him again, and then beat him viciously. Finally, because Rasputin was still alive, they bound him and tossed him into a freezing river. His body was discovered several days later and the two main conspirators, Youssupov and Pavlovich were exiled. It was the beginning of the end. The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 put an end to the imperial regime. Nicholas and Alexandra were murdered, and the long, dark reign of the Romanovs was over.

On January 22, 1905, while Russia was well on its way to losing a war against Japan in the Far East, the country found itself engulfed in internal discontent that finally exploded into violence in Saint Petersburg. The horrific events of the day became known as the Bloody Sunday Massacre. Russia had been under the rule of Romanov Czar Nicholas II who had ascended to the throne in 1894. Czar Nicholas II was a weak-willed man who was more concerned that his line would not continue, because his only son Alexis suffered from hemophilia, than he was about the corruption going on in his own administration. Before long, Nicholas fell under the influence of such unsavory characters as Grigory Rasputin, the so-called mad monk. As corruption and an oppressive regime often do, Russia’s imperialist interests in Manchuria at the turn of the century brought on the Russo-Japanese War, which began in February 1904. Behind the scenes, revolutionary leaders, such as the exiled Vladimir Lenin, were gathering forces of socialist rebellion aimed at toppling the czar.

On January 22, 1905, while Russia was well on its way to losing a war against Japan in the Far East, the country found itself engulfed in internal discontent that finally exploded into violence in Saint Petersburg. The horrific events of the day became known as the Bloody Sunday Massacre. Russia had been under the rule of Romanov Czar Nicholas II who had ascended to the throne in 1894. Czar Nicholas II was a weak-willed man who was more concerned that his line would not continue, because his only son Alexis suffered from hemophilia, than he was about the corruption going on in his own administration. Before long, Nicholas fell under the influence of such unsavory characters as Grigory Rasputin, the so-called mad monk. As corruption and an oppressive regime often do, Russia’s imperialist interests in Manchuria at the turn of the century brought on the Russo-Japanese War, which began in February 1904. Behind the scenes, revolutionary leaders, such as the exiled Vladimir Lenin, were gathering forces of socialist rebellion aimed at toppling the czar.

No one wanted to go to war with Japan, and it was going to take some work to drum up support for the unpopular war. The Russian government allowed a conference of the zemstvos to take the lead. A zemstvo was an institution of local government set up during the great emancipation reform of 1861 and carried out in Imperial Russia by Emperor Alexander II of Russia. The first zemstvo laws went into effect in 1864. After the October Revolution the zemstvo system was shut down by the Bolsheviks and replaced with a multilevel system of workers’ and peasants’ councils…the regional governments instituted by Nicholas’s grandfather Alexander II, in St. Petersburg in November 1904. The demands for reform made at this congress went unmet and more radical socialist and workers’ groups decided to take a different tack.

Things exploded on January 22, 1905, when a group of workers led by the radical priest Georgy Apollonovich Gapon marched to the czar’s Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg to make their demands. the imperial forces

immediately opened fire on the demonstrators, killing and wounding hundreds. Strikes and riots broke out throughout the country in outraged response to the massacre. Czar Nicholas responded by promising the formation of a series of representative assemblies, or Dumas, to work toward reform. Unfortunately, he did not follow through with his promise, and internal tension in Russia continued to build over the next decade. As the regime proved unwilling to truly change its repressive ways and radical socialist groups, including Lenin’s Bolsheviks, became stronger, drawing ever closer to their revolutionary goals, the situation grew worse. Finally, more than 10 years later, everything came to a head as Russia’s resources were stretched to the breaking point by the demands of World War I.

immediately opened fire on the demonstrators, killing and wounding hundreds. Strikes and riots broke out throughout the country in outraged response to the massacre. Czar Nicholas responded by promising the formation of a series of representative assemblies, or Dumas, to work toward reform. Unfortunately, he did not follow through with his promise, and internal tension in Russia continued to build over the next decade. As the regime proved unwilling to truly change its repressive ways and radical socialist groups, including Lenin’s Bolsheviks, became stronger, drawing ever closer to their revolutionary goals, the situation grew worse. Finally, more than 10 years later, everything came to a head as Russia’s resources were stretched to the breaking point by the demands of World War I.