copper

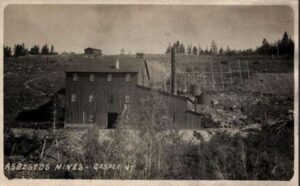

For people who live in Casper, Wyoming, the mountain to the south has long been a great recreation area. They are campgrounds and a ski resort, not to mention the trails that dot the mountain top. While the mountain is mostly recreational today, along with a number of people who live on the mountain full-time, that wasn’t always the case. In 1890, a gold strike on Casper Mountain brought a little gold rush to the area…along with many different kinds of people, looking to strike it rich. The mountain was crawling with people from all walks of life, but while they looked until 1895, they didn’t find much gold. The materials found were mostly asbestos and other non-profitable minerals.

For people who live in Casper, Wyoming, the mountain to the south has long been a great recreation area. They are campgrounds and a ski resort, not to mention the trails that dot the mountain top. While the mountain is mostly recreational today, along with a number of people who live on the mountain full-time, that wasn’t always the case. In 1890, a gold strike on Casper Mountain brought a little gold rush to the area…along with many different kinds of people, looking to strike it rich. The mountain was crawling with people from all walks of life, but while they looked until 1895, they didn’t find much gold. The materials found were mostly asbestos and other non-profitable minerals.

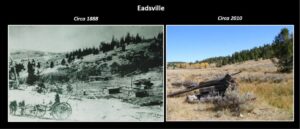

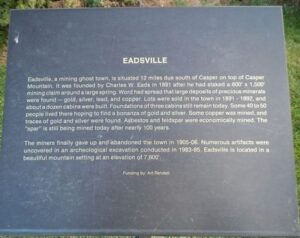

Nevertheless, there arose a need for a town and supply stores, so the town of Eadsville was formed. It was located 12 miles due south of Casper on top of Casper Mountain. It was founded by Charles W Eads in 1891 after he had staked a 600-foot x 1,500-foot mining claim around a large spring. The town was named for one Charles W Eads, who was the second person to settle in Casper, following a Mr. Merritt, who was credited with being the first to locate to Casper. Eads appeared in the Natrona County Tribune, May 13, 1908, and was apparently accused of being a horse thief. He would go on to do time in prison.

It was thought that there were large deposits of precious minerals, such as gold, silver, lead, and copper. The town continued to develop, with lots being sold in the town during 1891 – 1892. During that time, about a dozen cabins were built. While the town became a ghost town before very long, the foundations of three cabins still remain today. During the boom years, some 40 to 50 people lived there, all hoping to make their millions in gold and silver. Some traces of gold and silver were found, and copper was also mined, but asbestos and feldspar were the most economical to mined. The “spar” was still being mined after nearly 100 years. It’s no longer being mined, but it could be again, if there was a need.

After a time of trying unsuccessfully to make a living, the miners finally gave up and abandoned the town

between 1905 and 1906. The site was rediscovered in the 1980s, and numerous artifacts were uncovered during an archeological excavation that was conducted between 1983 and 1985. At one time it was surveyed as a stamp mill. Eadsville was located on Casper Mountain at an elevation of 7,800 feet and covered an area 20 acres.

between 1905 and 1906. The site was rediscovered in the 1980s, and numerous artifacts were uncovered during an archeological excavation that was conducted between 1983 and 1985. At one time it was surveyed as a stamp mill. Eadsville was located on Casper Mountain at an elevation of 7,800 feet and covered an area 20 acres.

When the minerals in a mine run out, or become less valuable, the mine tends to close down. These days, they try to return the mine to it’s prior state, but then many mines these days are pit mines, or strip mines. I suppose it is easier to return them to their prior state when you only have to fill in the hole, and I’m not opposed to that process. It can make a beautiful place out of ground that has been ripped apart. In some cases, it looks better after the reclamation.

When the minerals in a mine run out, or become less valuable, the mine tends to close down. These days, they try to return the mine to it’s prior state, but then many mines these days are pit mines, or strip mines. I suppose it is easier to return them to their prior state when you only have to fill in the hole, and I’m not opposed to that process. It can make a beautiful place out of ground that has been ripped apart. In some cases, it looks better after the reclamation.

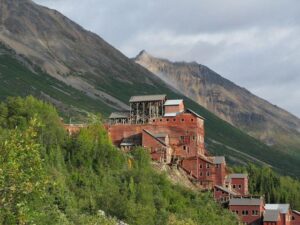

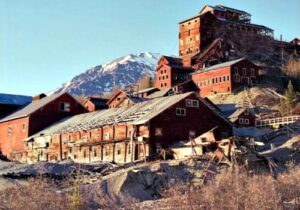

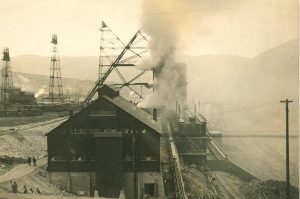

The Kennecott Mine, often spelled Kennicott, is an abandoned mining camp in the Valdez-Cordova Census Area, which is now the Copper River Census Area in the state of Alaska. The mine was, at one time, the center of activity for several copper mines. Kennecott Mines was named after the Kennicott Glacier in the valley below. The geologist Oscar Rohn named the glacier after Robert Kennicott during the 1899 US Army Abercrombie Survey. A “clerical error” resulted in the substitution of an “e” for the “i,” supposedly by Stephen Birch himself. The mine is located northeast of Valdez, inside Wrangell-Saint Elias National Park and Preserve. The camp and mines are now a National Historic Landmark District administered by the National Park Service. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1986. It’s status as a historical site, probably explains the good shape it is in. Many historical sites deteriorate badly before anyone realizes that they should be preserved as a part of history.

Two prospectors, “Tarantula” Jack Smith and Clarence L Warner, who were with a group of prospectors associated with the McClellan party in the summer of 1900, spotted “a green patch far above them in an  improbable location for a grass-green meadow.” Upon inspection, the green turned out to be malachite, located with chalcocite…aka “copper glance,” and the location of the Bonanza claim. A few days later, Arthur Coe Spencer, US Geological Survey geologist also found chalcocite at the same location. It was the birth of a copper mine.

improbable location for a grass-green meadow.” Upon inspection, the green turned out to be malachite, located with chalcocite…aka “copper glance,” and the location of the Bonanza claim. A few days later, Arthur Coe Spencer, US Geological Survey geologist also found chalcocite at the same location. It was the birth of a copper mine.

A mining engineer just out of school, named Stephen Birch was in Alaska looking for investment opportunities in minerals. He was young, but he came with the financial backing of the Havemeyer Family and another investor named James Ralph, from his days in New York. Birch spent the winter of 1901-1902 acquiring the “McClellan group’s interests” for the Alaska Copper Company of Birch, Havemeyer, Ralph and Schultz, later to become the Alaska Copper and Coal Company. He spent the summer of 1901, visiting the property and “spent months mapping and sampling.” He confirmed the Bonanza mine and surrounding deposits, were at the time, the richest known concentration of copper in the world.

Kennecott had five mines: Bonanza, Jumbo, Mother Lode, Erie, and Glacier. “Glacier, which is really an ore extension of the Bonanza, was an open-pit mine and was only mined during the summer. Bonanza and Jumbo were on Bonanza Ridge about 3 miles from Kennecott. The Mother Lode mine was located on the east side of the ridge from Kennecott. The Bonanza, Jumbo, Mother Lode and Erie mines were connected by tunnels. The Erie mine was perched on the northwest end of Bonanza Ridge overlooking Root Glacier about 3.7 miles up a glacial trail from Kennecott.” The copper ore was transported to Kennecott by way of the trams which head-ended at Bonanza and Jumbo. From Kennecott the ore was hauled mostly in 140-pound sacks on steel flat cars  to Cordova, 196 rail miles away on the Copper River and Northwestern Railway (CRNW).

to Cordova, 196 rail miles away on the Copper River and Northwestern Railway (CRNW).

In 1925 a Kennecott geologist predicted that the end of the high-grade ore bodies was in sight. The mines days were numbered. The highest grades of ore were largely depleted by the early 1930s. The Glacier Mine closed in 1929, and the rest followed soon after. The last train left Kennecott on November 10, 1938. It was now a ghost town. Over a period of 20 years the population dropped from 494 in 1920 to 5 in 1940. Thankfully the historical value of this particular site was not lost, and is still there today.

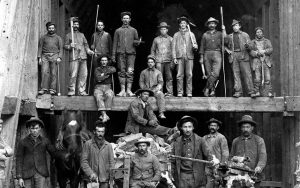

It is in times of greatest need, that people seem to best show that they can pull together to accomplish the greatest tasks. During World War I, the city of Butte, Montana was already a unionized industrial city with a population of 91,000 people. The city was home to one of the largest mining operations in the world. Butte was home to a copper mine system consisting of the Granite Mountain and Speculator Mines, and because of the heightened need for copper at that time, the abundance of employment opportunities drew workers from every corner of the world. The influx of people from other corners meant that more than 30 languages were spoken among the city streets. “No Smoking” signs posted in the mines were printed in 16 different languages, so that there was no mistaking the dangers.

It is in times of greatest need, that people seem to best show that they can pull together to accomplish the greatest tasks. During World War I, the city of Butte, Montana was already a unionized industrial city with a population of 91,000 people. The city was home to one of the largest mining operations in the world. Butte was home to a copper mine system consisting of the Granite Mountain and Speculator Mines, and because of the heightened need for copper at that time, the abundance of employment opportunities drew workers from every corner of the world. The influx of people from other corners meant that more than 30 languages were spoken among the city streets. “No Smoking” signs posted in the mines were printed in 16 different languages, so that there was no mistaking the dangers.

In April of 1917, the United States’ involvement in World War I was in its fourth month, and Butte mines increased their production of copper by operating around the clock, working the 14,500 miners like mules in order to meet the ever increasing demand. Unfortunately, this also brought steadily deteriorating safety conditions. Many of the miners were sleeping in shifts, so the beds in the boarding houses often never went cold. Despite these demanding work conditions, Butte miners worked with a pride and determination seldom found above ground, let alone a half-mile below the surface of the earth. They felt the weight of their duty to the war effort, and they gladly performed their jobs to the best of their abilities. Each day, the men were lowered into the mine, and the previous crew was brought out.

On the evening of June 8, 1917, 410 men were lowered into the Granite Mountain shaft to begin another backbreaking night shift. The exiting day shift had been tasked with the process of lowering a three-ton electric  cable down the shaft to complete work on a sprinkler system designed to protect the mine against fire. All seemed to be going well, but at 8:00 pm the cable slipped from its clamps. As it fell into a tangled coil below the 2400 foot level of the mine, the lead covering was torn away. The torn covering exposed a large portion of oiled paraffin paper, which was used to insulate the cable. Unfortunately, the oiled paraffin paper was also highly flammable. At 11:30 pm four men went down to examine the cable. One of the men accidentally touched his handheld carbide lamp to the oiled paraffin insulation, which immediately ignited. The flame spread quickly to the shaft timbers. The Granite Mountain and Speculator shafts immediately filled with thick, toxic smoke.

cable down the shaft to complete work on a sprinkler system designed to protect the mine against fire. All seemed to be going well, but at 8:00 pm the cable slipped from its clamps. As it fell into a tangled coil below the 2400 foot level of the mine, the lead covering was torn away. The torn covering exposed a large portion of oiled paraffin paper, which was used to insulate the cable. Unfortunately, the oiled paraffin paper was also highly flammable. At 11:30 pm four men went down to examine the cable. One of the men accidentally touched his handheld carbide lamp to the oiled paraffin insulation, which immediately ignited. The flame spread quickly to the shaft timbers. The Granite Mountain and Speculator shafts immediately filled with thick, toxic smoke.

There was a mad scramble to find a way of escape. Just over half of the men working in the Granite Mountain shaft were able to find an escape to the surface. One group of 29 men built a bulkhead to isolate themselves from the smoke and gas. They stayed there for 38 hours before making their way to safety. At the 2254 foot level, another group of 8 men were found behind a makeshift bulkhead over 50 hours from the start of the fire. Two of these men died shortly before their rescue, but the other six were recovered safely. Though the intensity of the fire cannot be disputed, only two men were actually burned to death in a rescue attempt at the onset of the blaze. The rest were simply trapped and overcome by the noxious, suffocating fumes. By the close of the rescue operation on June 16, 1917, eight days after the fire had begun, the death toll had reached its final tally of 168 men.

The Granite Mountain and Speculator Mine Fire was the worst disaster in metal mining history. And we could leave it at that, but then we would be overlooking a remarkable accomplishment…the rescue mission. Over the  course of just 7 days, rescue crews succeeded in searching over 30 miles of drifts and crosscuts, and at least 15 miles of stopes, raises, and manways. Townspeople turned out in droves to help in whatever way the could. All this was done in mine shafts saturated with carbon monoxide and dense, tar-laden smoke. In all, 155 bodies were recovered and removed, all without the loss of a single rescue worker. Despite the tremendous damage the fire caused to the Granite Mountain Mine, it did not stop the work being done there. Copper ore continued to be mined until the mine’s close in 1923. The Butte mines produced the copper that helped electrify America and win World War I. Through this horrible tragedy, Butte received a very special moniker. The city was being called “The Richest Hill on Earth, referencing the soul and determination of the community, rather than the value of the ore beneath its feet.”

course of just 7 days, rescue crews succeeded in searching over 30 miles of drifts and crosscuts, and at least 15 miles of stopes, raises, and manways. Townspeople turned out in droves to help in whatever way the could. All this was done in mine shafts saturated with carbon monoxide and dense, tar-laden smoke. In all, 155 bodies were recovered and removed, all without the loss of a single rescue worker. Despite the tremendous damage the fire caused to the Granite Mountain Mine, it did not stop the work being done there. Copper ore continued to be mined until the mine’s close in 1923. The Butte mines produced the copper that helped electrify America and win World War I. Through this horrible tragedy, Butte received a very special moniker. The city was being called “The Richest Hill on Earth, referencing the soul and determination of the community, rather than the value of the ore beneath its feet.”