coast guard

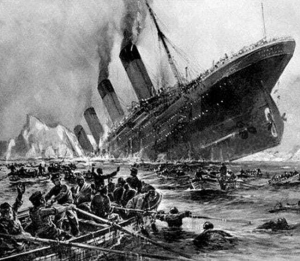

Following the Titanic disaster, a strange kind of job was formed…that of an iceberg mover. This was something I had never heard of, and it seems rather strange. I am aware that icebergs are chucks of ice, and obviously that they float, but to have the job of actually keeping track of an iceberg’s location so that you can go out to move it out of the shipping lanes is a really odd job, if you ask me. Still, the icebergs floating in the oceans, were a serious danger to the ships. Even if other ships were in the area and had seen the icebergs, that doesn’t mean other ships couldn’t fall prey to the icebergs. Many of those ships shut down their radios overnight…the most dangerous time for icebergs.

Following the Titanic disaster, a strange kind of job was formed…that of an iceberg mover. This was something I had never heard of, and it seems rather strange. I am aware that icebergs are chucks of ice, and obviously that they float, but to have the job of actually keeping track of an iceberg’s location so that you can go out to move it out of the shipping lanes is a really odd job, if you ask me. Still, the icebergs floating in the oceans, were a serious danger to the ships. Even if other ships were in the area and had seen the icebergs, that doesn’t mean other ships couldn’t fall prey to the icebergs. Many of those ships shut down their radios overnight…the most dangerous time for icebergs.

The job of the iceberg movers was to keep track of the icebergs and if they moved into the shipping lanes, to go in and move them to a different location. Now, that makes me wonder how heavy the icebergs were, and how hard it would be to move them. I also wonder how dangerous it would be, since icebergs have an uncanny knack for flipping over. Of course, iceberg movers are in a boat. Still, it’s hard to say what things can go wrong when an iceberg flips over. I really don’t think this would be a job I would want.

It seems like they might have had trouble hiring people to do this job, or maybe they just needed a more stable crew of men for the job. Whatever the case may be, The International Ice Patrol (IIP), was founded a year later. The IIP is operated by the US Coast Guard. The IIP tracks the location of icebergs and provides safe routes around them. If an iceberg is in a particularly unsafe area, it might become necessary to move it. Then, the iceberg will be towed out of the area. There is no way that they will be able to stop shipwrecks from

happening, but if we can remove the dangers created by icebergs, maybe we will see a few less shipwrecks in the future. Since Titanic, there have been five ship that went down after hitting an iceberg. Lives were lost in the first two following Titanic, but in the last three, everyone was saved. The last one was in 2007.

happening, but if we can remove the dangers created by icebergs, maybe we will see a few less shipwrecks in the future. Since Titanic, there have been five ship that went down after hitting an iceberg. Lives were lost in the first two following Titanic, but in the last three, everyone was saved. The last one was in 2007.

The ship that would eventually become the USS Serpens was built by California Shipbuilding Corporation in Wilmington, California. The ship was laid down March 10, 1943, as EC2 class Liberty Ship that was initially named SS Benjamin N. Cardozo (MCE hull 739). In the course of a little more than a month, SS Cardozo was transferred to the US Navy (USN) on April 19, 1943, and renamed USS Serpens (AK-97) after the star constellation Serpens. USS Serpens was commissioned May 28, 1943, at San Diego, and assigned to Captain Magnus J. Johnson, USCGR and manned by a crew from the US Coast Guard (USCG). From there, the ship led a relatively normal “life” for a ship. At least until the evening of January 29, 1945, when the USS Serpens (AK 97) was anchored off Lunga Beach, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. The Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Commander Perry L Stinson, and some of the enlisted men were ashore performing administrative functions.

The ship that would eventually become the USS Serpens was built by California Shipbuilding Corporation in Wilmington, California. The ship was laid down March 10, 1943, as EC2 class Liberty Ship that was initially named SS Benjamin N. Cardozo (MCE hull 739). In the course of a little more than a month, SS Cardozo was transferred to the US Navy (USN) on April 19, 1943, and renamed USS Serpens (AK-97) after the star constellation Serpens. USS Serpens was commissioned May 28, 1943, at San Diego, and assigned to Captain Magnus J. Johnson, USCGR and manned by a crew from the US Coast Guard (USCG). From there, the ship led a relatively normal “life” for a ship. At least until the evening of January 29, 1945, when the USS Serpens (AK 97) was anchored off Lunga Beach, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. The Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Commander Perry L Stinson, and some of the enlisted men were ashore performing administrative functions.

The remaining 970 crew members were loading depth charges when the USS Serpens suddenly exploded, leaving only the bow of the ship visible. The explosion was devastating, and only two sailors aboard…SN 1/C Kelsie K Kemp and SN 1/C George S Kennedy survived by clinging to the bow section of the ship, after escaping  from the “bosun’s hole” inside the ship. The rest of the crew consisting of 198 Coast Guardsmen, 56 US Army stevedores, and Dr Levin, a US Public Health Service surgeon, died…most instantly. Of the 198 US Coast Guardsmen, 167 were reservists. In the immense explosion, nearby ships were damaged, and a US Army soldier on the beach was killed. The loss of the USS Serpens remains the largest single disaster ever suffered by the Coast Guard.

from the “bosun’s hole” inside the ship. The rest of the crew consisting of 198 Coast Guardsmen, 56 US Army stevedores, and Dr Levin, a US Public Health Service surgeon, died…most instantly. Of the 198 US Coast Guardsmen, 167 were reservists. In the immense explosion, nearby ships were damaged, and a US Army soldier on the beach was killed. The loss of the USS Serpens remains the largest single disaster ever suffered by the Coast Guard.

An eyewitness account of the disaster stated that, “As we headed our personnel boat shoreward the sound and concussion of the explosion suddenly reached us, and, as we turned, we witnessed the awe-inspiring death drams unfold before us. As the report of screeching shells filled the air and the flash of tracers continued, the water splashed throughout the harbor as the shells hit. We headed our boat in the direction of the smoke and as we came into closer view of what had once been a ship, the water was filled only with floating debris, dead fish, torn life jackets, lumber and other unidentifiable objects. The smell of death, and fire, and gasoline, and oil was evident and nauseating. This was sudden death, and horror, unwanted and unasked for, but complete.”

The Coast Guard initially though the explosion was an enemy attack. They actually continued to think that until  July 1947. By June 10, 1949, it was officially determined not to have been the result of enemy attack. Unfortunately, there would be no real answers as to what happened. The remains of the 250 men who lost their lives were originally buried at the Army, Navy, and Marine Cemetery in Guadalcanal with full military honors and religious services. Later, however, the remains were repatriated under the program for the return of World War II dead in 1949. The mass recommittal of the 250 unidentified dead took place in section 34 at MacArthur Circle, Arlington National Cemetery. The remains were placed in 52 caskets and buried in 28 graves near the intersection of Jesup and Grant Drives. The two survivors both earned the Purple Heart injuries sustained.

July 1947. By June 10, 1949, it was officially determined not to have been the result of enemy attack. Unfortunately, there would be no real answers as to what happened. The remains of the 250 men who lost their lives were originally buried at the Army, Navy, and Marine Cemetery in Guadalcanal with full military honors and religious services. Later, however, the remains were repatriated under the program for the return of World War II dead in 1949. The mass recommittal of the 250 unidentified dead took place in section 34 at MacArthur Circle, Arlington National Cemetery. The remains were placed in 52 caskets and buried in 28 graves near the intersection of Jesup and Grant Drives. The two survivors both earned the Purple Heart injuries sustained.

“Leave No Man Behind” is a creed often repeated and strictly followed by various units and soldiers. The interpretation of the phrase is applied to the treatment and extraction of the seriously wounded, the recovery of the body of military members killed in action, and the attempts to rescue or trade for prisoners of war. Technically, it didn’t really apply concerning the North Atlantic Ferry Route, also known as the Snowball Route. The route was a transport route used during World War II. It went from Goose Bay, Labrador to the one-way runway at Bluie West One on Greenland. Then, the route continued across to Keflavik, Iceland, for a refueling stop. From there it continued to Prestwick, Scotland and finally to England. The route was the United Kingdom’s World War II aerial lifeline, and was used by freighters, as well as European Theater of Operations-bound bombers and fighters…which means that my dad, Staff Sergeant Allen Lewis Spencer might have traveled this route on his way to Great Ashfield Army Airforce Base, Suffolk, England, where he was stationed during World War II.

“Leave No Man Behind” is a creed often repeated and strictly followed by various units and soldiers. The interpretation of the phrase is applied to the treatment and extraction of the seriously wounded, the recovery of the body of military members killed in action, and the attempts to rescue or trade for prisoners of war. Technically, it didn’t really apply concerning the North Atlantic Ferry Route, also known as the Snowball Route. The route was a transport route used during World War II. It went from Goose Bay, Labrador to the one-way runway at Bluie West One on Greenland. Then, the route continued across to Keflavik, Iceland, for a refueling stop. From there it continued to Prestwick, Scotland and finally to England. The route was the United Kingdom’s World War II aerial lifeline, and was used by freighters, as well as European Theater of Operations-bound bombers and fighters…which means that my dad, Staff Sergeant Allen Lewis Spencer might have traveled this route on his way to Great Ashfield Army Airforce Base, Suffolk, England, where he was stationed during World War II.

I don’t imagine that landings at Bluie West One on Greenland would be easy on the best of days, and if the weather was bad, it was going to be far worse, and if there was any airplane trouble, it was really going to get dicey. On November 5, 1942, a Douglas C-53 Skytrooper, a paratroop-outfitted version of the C-47, was heading westbound on the Snowball Route. The plane was empty except for its crew of two and three military passengers returning to the United States from Scotland. The Skytrooper never made it. The crew radioed that they had to make a forced landing on the Greenland ice cap and giving an approximate position. The airplane was intact, and apparently there were no injuries.

Now began the hardest part of the situation…rescue. The C-53 fired flares for the next two nights. The flares were seen at a weather station on the Greenland coast, and rescuers set out toward them on motorized sleds. The group expected to be back in three or four days, if the weather held, but their sleds broke down, and they never found the C-53. After that, the flares stopped, and the plane and crew would never be seen or heard of again. Meanwhile, a variety of eastbound B-17s, B-25s, and C-47s that were either already over Greenland or gassing up at Narsarsuaq, the famous Bluie West One base, were detoured for search duty. One of them was a B-17F originally bound for England. On November 9 it took off from Bluie West One, assigned to search the area where the C-53’s flares had last been seen. Aboard the Flying Fortress were its original six-man transport crew, an Army enlisted man they had picked up at Goose Bay and two volunteer observers who had jumped aboard at Bluie West One to help out…an offer they would no doubt regret.

Just as the B-17 reached its search area, it ran into bad weather. Following pilot, Lieutenant Armand Monteverde’s 180 around the weather, he headed back into the search grid, only to fly into a sudden whiteout. Suddenly, the sky, clouds, and ice all looked the same. It was as if the horizon disappeared. Monteverde had no choice but did the only thing he could and banked away to fly back to clearer air. But the B-17’s left wingtip caught the ground, and the airplane skidded onto the ice cap. It was a hard crash, with the bomber traveling only about 200 yards before splitting apart just behind the wings. The Fortress had come down atop an active glacier, spider-webbed with crevasses. It was like landing in the middle of a minefield. The entire broken-off tail section hung over a large open chasm, with another chasm yawning just in front of the bomber. One crewman suffered a broken arm, and others had bad cuts and bruises. Just four were unhurt.

Meanwhile, an RAF Douglas Havoc out of Gander, being ferried through a snowstorm by a Canadian crew, flew past its refueling stop at Narsarsuaq and put down on the ice before its tanks ran totally dry. The Canadians set out on foot for the coast. On November 18, a search plane out of BW-1 spotted the Havoc, but its crew was gone. Five days later, a Grumman J2F-4 Duck from the Coast Guard cutter Northland, landed on the southeast coast of Greenland. They found the crew’s trail, and followed their snowshoe tracks. The men had actually fabricated snowshoes from pieces stripped from the Havoc. That night, Northland fired off flares, and the Havoc crew spotted them. The in an act much like burning his bridges, one of the pilots responded by setting fire to his coat, which in Greenland in late November is a good way to freeze to death. Fortunately, the blazing parka was spotted by crewman aboard Northland, which put a rescue party ashore and found the Havoc crew.

On the morning of November 28, the cutter Northland dispatched their Grumman J2F-4, a plane known as the Duck into the hunt as well. On board were Coast Guard pilot Lieutenant John Pritchard Jr and his radioman, Petty Officer 1st Class Benjamin Bottoms. They took off for the B-17 crash site. Pritchard overflew the B-17 and radioed its crew for landing advice. “Don’t try it,” Corporal Howarth replied, “crevasses everywhere.” Colonel Balchen, coincidentally, was overhead at that moment in the DC-4, making a supply drop. Nevertheless, Pritchard found a smooth, sloped, apparently crevasse-free area a mile north of the B-17 and carefully touched down with his landing gear extended. He landed uphill, and the Duck quickly came to a stop. It was the very first successful landing of an airplane on the surface of Greenland’s ice cap. The Duck made two trips to rescue  the men in the B-17, the first successful; and the second with passenger, radioman Loren Howarth, ended in a crash that would leave the plane lost for seven decades.

the men in the B-17, the first successful; and the second with passenger, radioman Loren Howarth, ended in a crash that would leave the plane lost for seven decades.

Fast forward…to 2012, when a company by the name Global Exploration and Recovery found the remains of the Duck in 38 feet of ice, with its crew and passenger still onboard. GEaR believes in “Leave No Man Behind,” and does its best to find these downed war birds to bring them and their crew…finally home, if they are still in the planes. What a noble effort.

Originally, in the United States, each branch of the service had their own day to celebrate their service, but on August 31, 1949, Defense Secretary Louis Johnson announced the creation of an Armed Forces Day to replace separate Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard Days. There was a good reason for it. The combination coincided with the unification of the three branches of the service under one agency…the Department of Defense. Man countries have an Armed Forces Day, and they are all done a little differently. In the United States, Armed Forces Day is celebrated on the third Saturday in May, which is near the end of Armed Forces Week, which begins on the second Saturday of May and ends on the third Sunday of May, or the fourth Saturday if the month begins on a Sunday, such as in 2016. Following the creation of Armed Forces Day in 1949, the holiday was first observed on May 20, 1950.

Originally, in the United States, each branch of the service had their own day to celebrate their service, but on August 31, 1949, Defense Secretary Louis Johnson announced the creation of an Armed Forces Day to replace separate Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard Days. There was a good reason for it. The combination coincided with the unification of the three branches of the service under one agency…the Department of Defense. Man countries have an Armed Forces Day, and they are all done a little differently. In the United States, Armed Forces Day is celebrated on the third Saturday in May, which is near the end of Armed Forces Week, which begins on the second Saturday of May and ends on the third Sunday of May, or the fourth Saturday if the month begins on a Sunday, such as in 2016. Following the creation of Armed Forces Day in 1949, the holiday was first observed on May 20, 1950.

In his speech proclaiming the day as Armed Forces Day, on February 27, 1950, President Truman stated, “Armed Forces Day, Saturday, May 20, 1950, marks the first combined demonstration by America’s defense  team of its progress, under the National Security Act, toward the goal of readiness for any eventuality. It is the first parade of preparedness by the unified forces of our land, sea, and air defense.” Of course, there is more to planning a holiday that a day and a speech. The first Armed Forces Day was celebrated by parades, open houses, receptions, and air shows. The longest continuously running Armed Forces Day Parade in the United States is held in Bremerton, Washington.

team of its progress, under the National Security Act, toward the goal of readiness for any eventuality. It is the first parade of preparedness by the unified forces of our land, sea, and air defense.” Of course, there is more to planning a holiday that a day and a speech. The first Armed Forces Day was celebrated by parades, open houses, receptions, and air shows. The longest continuously running Armed Forces Day Parade in the United States is held in Bremerton, Washington.

There were a few glitches, however. The unique training schedules of the National Guard and Reserve units make the specific Saturday celebration difficult for these branches, so they have adapted to celebrate Armed Forces Day/Week over any period in the month of May. Every nation needs to celebrate the military forces. Where would we be without a strong military. As President Truman said, “It is vital to the security of the nation and to the establishment of a desirable peace.”

Each year, Armed Forces Day theme is different, because of course, each year more and more has changed. The very first theme was “Teamed for Defense.” Over the years, other themes have included Appreciation of a Nation; Arsenal of Freedom and Democracy; Dedication and Devotion; Deter if Possible, Fight if Necessary;  Freedom; Freedom Through Unity; Guardians of Peace; Lasting Peace; Liberty; and Patriotism. In Washington DC, 10,000 troops of all branches of the military, cadets, and veterans marched past the president and his party. In New York City, an estimated 33,000 participants initiated Armed Forces Day “under an air cover of 250 military planes of all types.” Today, Armed Forces Day is celebrated in American communities and on military bases throughout the world with parades, picnics, shopping discounts, festivals, and parties. On May 19, 2017, President Donald Trump reaffirmed the Armed Forces Day holiday, marking the 70th anniversary since the creation of the Department of Defense.

Freedom; Freedom Through Unity; Guardians of Peace; Lasting Peace; Liberty; and Patriotism. In Washington DC, 10,000 troops of all branches of the military, cadets, and veterans marched past the president and his party. In New York City, an estimated 33,000 participants initiated Armed Forces Day “under an air cover of 250 military planes of all types.” Today, Armed Forces Day is celebrated in American communities and on military bases throughout the world with parades, picnics, shopping discounts, festivals, and parties. On May 19, 2017, President Donald Trump reaffirmed the Armed Forces Day holiday, marking the 70th anniversary since the creation of the Department of Defense.

Overdue is never a good thing, but there are some times when being overdue is a very bad thing. One of those times is when a plane, train, or ship are overdue. Andrea Gail began her final voyage departing from Gloucester Harbor, Massachusetts, on September 20, 1991, bound for the Grand Banks of Newfoundland off the coast of eastern Canada. After poor fishing, Captain Frank W “Billy” Tyne Jr headed east to the Flemish Cap where he believed they would have better luck. The fishing was much better there, and before long, the crew had filled the storage bins with fish. It was at that point that the ship’s ice machine began malfunctioning. Because they could not maintain the catch without the ice, Tyne set course for home on October 26–27.

Overdue is never a good thing, but there are some times when being overdue is a very bad thing. One of those times is when a plane, train, or ship are overdue. Andrea Gail began her final voyage departing from Gloucester Harbor, Massachusetts, on September 20, 1991, bound for the Grand Banks of Newfoundland off the coast of eastern Canada. After poor fishing, Captain Frank W “Billy” Tyne Jr headed east to the Flemish Cap where he believed they would have better luck. The fishing was much better there, and before long, the crew had filled the storage bins with fish. It was at that point that the ship’s ice machine began malfunctioning. Because they could not maintain the catch without the ice, Tyne set course for home on October 26–27.

The weather reports warned of dangerous weather conditions, and he knew it would be risky, but he thought they could make a run for home, and possibly beat the storm. The problem was that this was no ordinary storm. Two systems were colliding, and creating the perfect storm. It was the perfect situation for an impossible passage for the Andrea Gail. His friend, Linda Greenlaw, tried to warn Tyne not to try it. She was looking at the weather report and she could see that this storm was not one to be taken lightly. Nevertheless, Tyne headed for Massachusetts. His last reported transmission was at about 6:00pm on October 28, 1991, when he radioed Greenlaw, who was the Captain of the Hannah Boden, and gave his coordinates as 44°00 N 56°40 W, or about 162 miles east of Sable Island. He also gave a weather report indicating 30 foot seas and wind gusts up to 80 knots. Tyne’s final recorded words were “She’s comin’ on, boys, and she’s comin’ on strong.” It was reported that the storm created waves in excess of 100 feet in height, but ocean buoy monitors recorded a peak wave height of 39 feet, and so waves of 100 feet were deemed “unlikely” by Science Daily. However, data from a series of weather buoys in the general vicinity of the vessel’s last known location recorded peak wave action exceeding 60 feet in height from October 28 through 30, 1991.

The Andrea Gail was officially reported overdue on October 30, 1991. An extensive air and land search was launched by the 106th Rescue Wing from the New York Air National Guard, United States Coast Guard and Canadian Coast Guard forces. The search would eventually cover over 186,000 square nautical miles. Finally, on November 6, 1991, Andrea Gail’s emergency position-indicating radio beacon (EPIRB) was discovered  washed up on the shore of Sable Island in Nova Scotia…not the news they were hoping for. The EPIRB was designed to automatically send out a distress signal upon contact with sea water, but the Canadian Coast Guard personnel who found the beacon “did not conclusively verify whether the control switch was in the on or off position”. By November 9th, authorities officially called off the search for the missing Andrea Gail, due to the low probability of crew survival. Fuel drums, a fuel tank, the EPIRB, an empty life raft, and some other flotsam were the only wreckage ever found. The ship was presumed lost at sea somewhere along the continental shelf near Sable Island. Sometimes, overdue is the worst possible situation.

washed up on the shore of Sable Island in Nova Scotia…not the news they were hoping for. The EPIRB was designed to automatically send out a distress signal upon contact with sea water, but the Canadian Coast Guard personnel who found the beacon “did not conclusively verify whether the control switch was in the on or off position”. By November 9th, authorities officially called off the search for the missing Andrea Gail, due to the low probability of crew survival. Fuel drums, a fuel tank, the EPIRB, an empty life raft, and some other flotsam were the only wreckage ever found. The ship was presumed lost at sea somewhere along the continental shelf near Sable Island. Sometimes, overdue is the worst possible situation.

A number of my ancestors came to America during and prior to the years that Ellis Island was the processing center in New York. I have no doubt that some of them came through Ellis Island, but I have not confirmed that. I find many of the names in my tree, but while many of the ancestors I have found came over by way of New York, it would appear that my direct line arrived in America before the immigration center at Ellis Island opened on January 2, 1892. Before that time, immigrants were handled by the individual states where the immigrant first arrived. It is estimated that about 40% of Americans can trace their roots through Ellis Island, so while I see many familiar names, they may or may not be my direct line, and in fact, they might not be related at all.

A number of my ancestors came to America during and prior to the years that Ellis Island was the processing center in New York. I have no doubt that some of them came through Ellis Island, but I have not confirmed that. I find many of the names in my tree, but while many of the ancestors I have found came over by way of New York, it would appear that my direct line arrived in America before the immigration center at Ellis Island opened on January 2, 1892. Before that time, immigrants were handled by the individual states where the immigrant first arrived. It is estimated that about 40% of Americans can trace their roots through Ellis Island, so while I see many familiar names, they may or may not be my direct line, and in fact, they might not be related at all.

Ellis Island is located in New York Harbor off the New Jersey coast and was named for merchant Samuel Ellis, who owned the land in the 1770s. The island was given the nickname, The Gateway to America because more than 12 million immigrants passed through the center since it opened in 1892. On January 2, 1892, 15 year old Annie Moore, from Ireland, became the first person to pass through the newly opened Ellis Island, which President Benjamin Harrison designated as America’s first federal immigration center in 1890. Oddly, not all  immigrants who sailed into New York had to go through Ellis Island. First and second class passengers were just given a brief shipboard inspection and then disembarked at the piers in New York or New Jersey, where they passed through customs. People in third class, though, were transported to Ellis Island, where they underwent medical and legal inspections to ensure they didn’t have a contagious disease or some condition that would make them a burden to the government. Nevertheless, only two percent of all immigrants were denied entrance into the United States. The peak years of immigration through Ellis Island were from 1892 to 1924. The 3.3 acre island was enlarged by landfill, and by the 1930s, it had reached its current size of 27.5 acres. After the extra size was completed, new buildings were constructed to handle the massive influx of people coming to America for a better life. During it’s busiest year, which was 1907, over 1 million people were processed through Ellis Island.

immigrants who sailed into New York had to go through Ellis Island. First and second class passengers were just given a brief shipboard inspection and then disembarked at the piers in New York or New Jersey, where they passed through customs. People in third class, though, were transported to Ellis Island, where they underwent medical and legal inspections to ensure they didn’t have a contagious disease or some condition that would make them a burden to the government. Nevertheless, only two percent of all immigrants were denied entrance into the United States. The peak years of immigration through Ellis Island were from 1892 to 1924. The 3.3 acre island was enlarged by landfill, and by the 1930s, it had reached its current size of 27.5 acres. After the extra size was completed, new buildings were constructed to handle the massive influx of people coming to America for a better life. During it’s busiest year, which was 1907, over 1 million people were processed through Ellis Island.

When the United States entered into World War I, immigration to the United States decline, most likely because travel anywhere was risky. Ellis Island was used as a detention center for suspected enemies during that time. Following the war, Congress passed quota laws and the Immigration Act of 1924, which sharply reduced the number of newcomers allowed into the country and also enabled immigrants to be processed at United States  consulates abroad. The act also enabled immigrants to be processed at United States consulates abroad, making detention at Ellis Island obsolete. After 1924, Ellis Island switched from a processing center to other purposes, such as a detention and deportation center for illegal immigrants, a hospital for wounded soldiers during World War II and a Coast Guard training center. In November 1954, the last detainee, a Norwegian merchant seaman, was released and Ellis Island officially closed on November 12, 1954. In 1984, Ellis Island underwent a $160 million renovation, the largest historic restoration project in United States history. In September 1990, the Ellis Island Immigration Museum opened to the public and is visited by almost 2 million people each year.

consulates abroad. The act also enabled immigrants to be processed at United States consulates abroad, making detention at Ellis Island obsolete. After 1924, Ellis Island switched from a processing center to other purposes, such as a detention and deportation center for illegal immigrants, a hospital for wounded soldiers during World War II and a Coast Guard training center. In November 1954, the last detainee, a Norwegian merchant seaman, was released and Ellis Island officially closed on November 12, 1954. In 1984, Ellis Island underwent a $160 million renovation, the largest historic restoration project in United States history. In September 1990, the Ellis Island Immigration Museum opened to the public and is visited by almost 2 million people each year.

The USCGC Spencer (WMEC-905) is a U S Coast Guard medium endurance cutter. It was named after my 5th cousin 5 times removed, John Canfield Spencer. He was born January 8, 1788 in Hudson, New York, and died May 18, 1855 in Albany, New York. During the War of 1812, he served in the U S Army where he was appointed the brigade judge advocate general for the northern frontier. John was the 17th Secretary of War from October 12, 1841 to March 4, 1843 and the 16th Secretary of the Treasurer from March 8, 1843 to May 2, 1844, under President John Tyler. As one of few northerners in an administration dominated by southern interests, John found it was becoming increasingly difficult to serve in his cabinet post, so he resigned as Treasury Secretary in May of 1844.

The USCGC Spencer (WMEC-905) is a U S Coast Guard medium endurance cutter. It was named after my 5th cousin 5 times removed, John Canfield Spencer. He was born January 8, 1788 in Hudson, New York, and died May 18, 1855 in Albany, New York. During the War of 1812, he served in the U S Army where he was appointed the brigade judge advocate general for the northern frontier. John was the 17th Secretary of War from October 12, 1841 to March 4, 1843 and the 16th Secretary of the Treasurer from March 8, 1843 to May 2, 1844, under President John Tyler. As one of few northerners in an administration dominated by southern interests, John found it was becoming increasingly difficult to serve in his cabinet post, so he resigned as Treasury Secretary in May of 1844.

WMEC-905 is the third cutter to serve the United States bearing the name “Spencer”. The history of Spencer started in 1843 when the original Spencer was commissioned to serve in the Revenue Cutter Service. An Iron hulled steamer, she served as a lightship off Hampton Roads, Virginia until 1848. The second cutter to carry the name Spencer was hull number W-36, commissioned in 1937. At a length of 327 feet, she first started service as a search and rescue unit patrolling Alaska’s fishing grounds. After the United States entered WWII, the Coast Guard temporarily became part of the US Navy. Spencer saw significant combat action in both the Atlantic and Pacific theaters. In the “Battle of the Atlantic”, Spencer acted as a convoy escort and hunted German submarines, sinking the U-225 and the U-175 in 1944. In late 1944, Spencer reported to the Navy’s Seventh (Pacific) Fleet as a Communications Command Ship. There she was credited with taking part in numerous amphibious invasions including Luzon and Palawan in the Philippines.

After the war, Spencer returned to her Coast Guard duties serving at an Atlantic Ocean Station. Here she provided navigational assistance for the fledgling trans-Atlantic air industry and more importantly, acted as a search and rescue platform for both airplanes and ships. In January 1969, Spencer returned to combat duty off the Coast of Vietnam. For ten months, she provided surveillance to prevent troops and supplies from getting into South Vietnam. In November 1969, Spencer returned to the United States to continue her peace time mission of ocean station keeping. The second Spencer served the nation for more then 37 years and when decommissioned in 1974, she was the most decorated cutter in the Coast Guard’s fleet.

The Spencer of today was commissioned into service on 28th of June 1986. She is credited for confiscating over 46,000 pounds of marijuana and 8800 pounds of cocaine. In 1991 she towed a disabled U.S. Navy frigate, twice her size, to safety, and participated in the search for a missing Air National Guard paratrooper during the “Perfect Storm”. In early 1996, she responded to the Alas Nacionales plane crash off the coastal waters of the Dominican

Republic in which 189 people were killed. When the fishing vessel Lady of Grace became disabled during a severe storm in November 1997, Spencer was there to save the crew and tow the vessel to safety. In 1999, Spencer was the on-scene commander for the crash of Egypt Air Flight 990 off Nantucket, controlling both U S Navy and Coast Guard assets in search and recovery efforts. In 2005, Spencer was an initial responder during Hurricane Katrina.

Republic in which 189 people were killed. When the fishing vessel Lady of Grace became disabled during a severe storm in November 1997, Spencer was there to save the crew and tow the vessel to safety. In 1999, Spencer was the on-scene commander for the crash of Egypt Air Flight 990 off Nantucket, controlling both U S Navy and Coast Guard assets in search and recovery efforts. In 2005, Spencer was an initial responder during Hurricane Katrina.

I would like to thank TxHwy105 and Len Eagleburger on Ancestry.com for providing the Spencer historical information and the US Coast Guard site for photos of the Spencer.