civil war

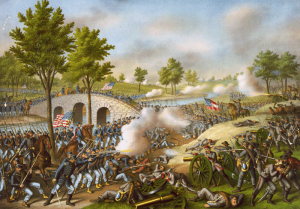

These days, with the many types of bombs nations use for warfare, it would be easy to annihilate an entire town, but during the Civil War…not so much. One bomb dropped on Hiroshima instantly killed 80,000 people. Of course that was on August 6, 1945, and not 1862. September 17, 1862 dawned slowly through the fog. It seemed like the start of a peacefully beautiful day, but looks can be deceiving. That morning, the soldiers were busy, trying to wipe away the dampness, when cannons began to roar and sheets of flame burst forth from hundreds of rifles. The bloodiest one-day battle in American History had begun. The Battle of Antietam was a 12-hour battle that swept across the rolling farm fields in western Maryland. It was this battle between North and South that changed the course of the Civil War, helped free over four million Americans, devastated Sharpsburg, and no other one-day battle would be as bloody.

These days, with the many types of bombs nations use for warfare, it would be easy to annihilate an entire town, but during the Civil War…not so much. One bomb dropped on Hiroshima instantly killed 80,000 people. Of course that was on August 6, 1945, and not 1862. September 17, 1862 dawned slowly through the fog. It seemed like the start of a peacefully beautiful day, but looks can be deceiving. That morning, the soldiers were busy, trying to wipe away the dampness, when cannons began to roar and sheets of flame burst forth from hundreds of rifles. The bloodiest one-day battle in American History had begun. The Battle of Antietam was a 12-hour battle that swept across the rolling farm fields in western Maryland. It was this battle between North and South that changed the course of the Civil War, helped free over four million Americans, devastated Sharpsburg, and no other one-day battle would be as bloody.

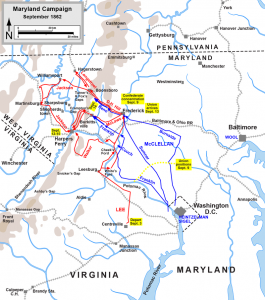

The Battle of Antietam marked the first invasion into the North by Confederate General Robert E Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. It was the culmination of the Maryland Campaign of 1862. Southern armies were also advancing in Kentucky and Missouri, as the tide of war flowed north. After Lee’s dramatic victory at the Second Battle of Manassas during the last two days of August, he wrote to Confederate President Jefferson Davis that “we cannot afford to be idle.” Lee wanted to keep the pressure on in order to secure Southern independence through victory in the North; influence the Fall mid-term elections; obtain much-needed supplies; move the war out of Virginia, possibly into Pennsylvania; and to liberate Maryland, a Union state, but a slave-holding border state divided in its values.

Lee’s army splashed across the Potomac River and arrived in Frederick, Virginia, where he boldly divided his army to capture the Union garrison stationed at Harpers Ferry. A vital location on the Confederate lines of supply and communication back to Virginia; Harpers Ferry, Maryland was the gateway to the Shenandoah Valley. Lee’s link to the south was threatened by the 12,000 Union soldiers at Harpers Ferry. General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson and about half of the Army of Northern Virginia were sent to capture Harpers Ferry. The rest of the Confederates moved north and west toward South Mountain and Hagerstown, Maryland. The Confederate army soon retreated from South Mountain, and Lee considered returning to Virginia. However, with Jackson’s capture of Harpers Ferry on September 15th, Lee decided to make a stand at Sharpsburg.

Lee gathered his forces on the high ground west of Antietam Creek, with General James Longstreet’s command holding the center and the right, while Jackson’s men filled in on the left. The Confederate position was strengthened with the mobility provided by the Hagerstown Turnpike that ran north and south along Lee’s line. Still, the Potomac River behind them and only one crossing back to Virginia remained a risk. Lee and his men watched the Union army gather on the east side of Antietam Creek. Thousands of soldiers in blue marched into position throughout September 15th and 16th as General McClellan prepared for his attempt to drive Lee from Maryland. McClellan’s plan was to “attack the enemy’s left” and when “matters looked favorably,” attack the Confederate right, and “whenever either of those flank movements should be successful to advance our center.” As the opposing forces moved into position during the rainy night of September 16th, one Pennsylvanian remembered, “…all realized that there was ugly business and plenty of it just ahead.”

The twelve-hour battle began at dawn, and for the next seven hours, there were three major Union attacks on the Confederate left, moving from north to south. General Joseph Hooker’s command led the first Union assault. General Joseph Mansfield’s soldiers attacked second, followed by General Edwin Sumner’s men as McClellan’s plan broke down into a series of uncoordinated Union advances. The fierce battle raged across the Cornfield, East Woods, West Woods, and the Sunken Road as Lee shifted his men to withstand each of the Union thrusts. After clashing for over eight hours, Lee’s troops were pushed back, but not broken. Shockingly, over 15,000 soldiers were killed or wounded.

While the Union assaults were being made on the Sunken Road, a mile-and-a-half farther south, Union General Ambrose Burnside opened the attack on the Confederate right. He first sought to capture the bridge that would later bear his name, but a small Confederate force, positioned on higher ground, was able to delay Burnside for three hours. Finally, about 1:00pm Burnside captured the bridge, and then reorganized for two hours before moving forward across the difficult terrain…an unfortunate delay. When the advance did begin, it was turned back by Confederate General AP Hill’s reinforcements, who had arrived in the late afternoon from Harpers Ferry.

Neither flank of the Confederate army collapsed far enough for McClellan to advance his center attack, leaving a sizable Union force that never entered the battle. Despite an estimated 23,100 casualties of the nearly 100,000 engaged, both armies stubbornly held their ground as the sun set on the devastated landscape. The next day, September 18, 1862, the opposing armies gathered their wounded and buried their dead. That night  General Robert E Lee’s army withdrew back across the Potomac River to Virginia, ending his first invasion into the North. Lee’s retreat to Virginia provided President Abraham Lincoln the opportunity he had been waiting to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Now, the Civil War had a dual purpose of preserving the Union and ending slavery, which the United States had been trying to end since it was founded.

General Robert E Lee’s army withdrew back across the Potomac River to Virginia, ending his first invasion into the North. Lee’s retreat to Virginia provided President Abraham Lincoln the opportunity he had been waiting to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Now, the Civil War had a dual purpose of preserving the Union and ending slavery, which the United States had been trying to end since it was founded.

The Battle of Antietam was fought over an area of 12 square miles. Today the site consists of 184 acres containing approximately 5 miles of paved avenues. Located along the battlefield avenues to mark battle positions of infantry, artillery, and cavalry are many monuments, markers, and narrative tablets. Markers describe the actions at Turner’s Gap, Harpers Ferry, and Blackford’s Ford. Key artillery positions on the field of Antietam are marked by cannon. And 10 large-scale field exhibits at important points on the field indicate troop positions and battle action.

Gunfighters were a big part of what we think of when we think of the Old West. The reality is that there were probably a lot less gunfights that we have been led to believe, and most were not held in the way that we all think. Many were quickly started when tempers flared, and then over in a moment. The whole meeting on “Main Street at high noon” thing didn’t happen very much. Nevertheless, gunfighters were a part of the Old West and many were truly mean and evil people.

Gunfighters were a big part of what we think of when we think of the Old West. The reality is that there were probably a lot less gunfights that we have been led to believe, and most were not held in the way that we all think. Many were quickly started when tempers flared, and then over in a moment. The whole meeting on “Main Street at high noon” thing didn’t happen very much. Nevertheless, gunfighters were a part of the Old West and many were truly mean and evil people.

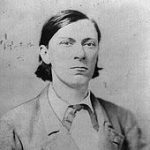

William “Texas Billy” Thompson (1845-1897), was the brother of the more famous gunman Ben Thompson. Apparently Billy felt the need to live up to an surpass his brother’s reputation. Billy was often described as “mean, vicious, vindictive and totally unpredictable.” Billy and his brother, Ben emigrated from Yorkshire, England with their family to Austin, Texas in 1851, when he was just a boy. When the Civil War began, both men enlisted in the Texas Mounted Rifles. After the war, there were a number of federal troops who remained in Texas for several years, which annoyed the people of Texas. In March, 1868, Billy was involved in a gunfight with a Private William Burk. After killing the soldier, Billy fled the area. Two months later, Billy killed another man in Rockport, Texas and when a warrant was issued for his arrest, he was on the run again, first to Indian Territory and then to Kansas.

While in Abilene, Kansas, Billy met a dance hall girl and prostitute named Elizabeth “Libby” Haley. Haley went by the alias of “Squirrel Tooth Alice.” The two quickly began an affair that would eventually lead to marriage and nine children. Billy made his living as a gambler. He and his brother Ben, were living in Ellsworth, Kansas in April, 1873. Four months later, in August, Billy’s temper got the best of him again, and killed Sheriff Chauncey Whitney. He was on the run again.

Billy had a reputation for constantly being trouble for one thing or another. This meant that Billy and Libby were constantly moving. The Texas Rangers finally caught up with Billy in October 1876, and was extradited to Kansas. Amazingly, he was acquitted of the murder of Sheriff Whitney. He must have had a great attorney, because everyone knew he did it. Billy made his way to Dodge City, Kansas. There is also evidence that places him in Colorado and Nebraska, before he and Libby finally settled down in Sweetwater, Texas. He purchased and worked a ranch, while she established a brothel in town. In 1884, he was reportedly in San Antonio and witnessed his brother being gunned down by assassins. Billy took no revenge on his brother’s killers. Maybe he had lost his taste for killing and running. On September 6, 1897, William Thompson died from a stomach ailment at the age of 52.

Nurses are the cornerstone of medicine in many cases. Yes, we must have doctors, but nurses are the support system that allows doctors to do their jobs. One such example was a woman named Mary Ann Bickerdyke. She was born on July 19, 1817 in Knox County, Ohio, to Hiram and Annie (Rodgers) Ball. She was married in 1847 to Robert Bickerdyke. The couple and their family moved to Galesburg, Illinois. After her infant daughter died suddenly, she vowed to learn more about medicine, studying herbal medicine at Oberlin College. Mary Ann was widowed in 1859. She was alone and the mother of two sons, who were in their adolescent years.

Nurses are the cornerstone of medicine in many cases. Yes, we must have doctors, but nurses are the support system that allows doctors to do their jobs. One such example was a woman named Mary Ann Bickerdyke. She was born on July 19, 1817 in Knox County, Ohio, to Hiram and Annie (Rodgers) Ball. She was married in 1847 to Robert Bickerdyke. The couple and their family moved to Galesburg, Illinois. After her infant daughter died suddenly, she vowed to learn more about medicine, studying herbal medicine at Oberlin College. Mary Ann was widowed in 1859. She was alone and the mother of two sons, who were in their adolescent years.

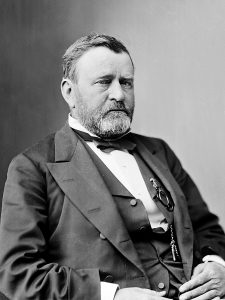

Widowed just two years before the Civil War began, she supported herself and her sons by practicing as a “botanic physician” in Galesburg. When a young Union volunteer physician wrote home about the filthy, chaotic military hospitals at Cairo, Illinois, the citizens of Galesburg collected $500 worth of supplies and selected Bickerdyke to deliver them. She left her sons with a neighbor, and after seeing the horrible conditions for herself, Bickerdyke decided that she was needed there, so she stayed as an unofficial nurse. Her never ending energy, and her dedication made her just the heroine the Union soldiers needed in those awful war years. She organized the hospitals and cleaned up the filth that served only to breed germs, and in doing so, she gained the respect and appreciation of Ulysses S. Grant.

While there, she worked alongside another famed Civil War Nurse, Mary J. Stafford. When Grant’s army moved down the Mississippi River, Bickerdyke went too, becoming the Chief of Nursing and setting up hospitals where  they were needed. Bickerdyke’s goal during the Civil War was to more efficiently care for wounded Union soldiers. She insisted on cleanliness, was dedicated to improving the level of care, and unafraid of stepping on male toes. That, in itself, was almost unheard of in that era. She was adamant about scrubbing every surface in sight, reported drunken physicians, and on one occasion ordered a staff member, who had illegally appropriated garments meant for the wounded, to strip. Though she antagonized male physicians, staff, and soldiers alike, in the name of better patient care, she won most of her battles…a good thing for the wounded soldiers.

they were needed. Bickerdyke’s goal during the Civil War was to more efficiently care for wounded Union soldiers. She insisted on cleanliness, was dedicated to improving the level of care, and unafraid of stepping on male toes. That, in itself, was almost unheard of in that era. She was adamant about scrubbing every surface in sight, reported drunken physicians, and on one occasion ordered a staff member, who had illegally appropriated garments meant for the wounded, to strip. Though she antagonized male physicians, staff, and soldiers alike, in the name of better patient care, she won most of her battles…a good thing for the wounded soldiers.

Union General William T. Sherman was especially fond of the volunteer nurse who followed the western armies. It is said that she was the only woman he would allow in his camp. When his staff complained about the outspoken, insubordinate female nurse who constantly disregarded the army’s red tape and military procedures, Sherman threw up his hands and exclaimed, “Well, I can do nothing for you, she outranks me.” Running roughshod over anyone who stood in the way of her self-appointed duties, when a surgeon questioned her authority to take some action, she replied, “On the authority of Lord God Almighty, have you anything that outranks that?” I guess Sherman was right when he said that she outranked him.

To the wounded soldiers, Bickerdyke was an angel. They affectionately called her “Mother” Bickerdyke, and she called them her “boys.” The soldiers would cheer here when she appeared. She was more loved than the celebrities of our day are for some fans. During the war, she worked closely with Eliza Emily Chappell Porter of the Northwest Sanitary Commission, worked on the first hospital boat, helped build 300 hospitals and aided the wounded on 19 battlefields including the Battle of Shiloh, the Battle of Vicksburg, and Sherman’s March to the  Sea. When the war was over, she rode at the head of the XV Corps in the Grand Review in Washington at General William T. Sherman’s request. Afterwards, she worked for the Salvation Army in San Francisco, and became an attorney, helping Union veterans with legal issues. Later, she ran a hotel in Salina, Kansas for a time before retiring to Bunker Hill, Kansas. She received a special pension of $25 a month from Congress in 1886. She died peacefully after a minor stroke November 8, 1901. Her remains were transported back to Galesburg, Illinois and she was interred next to her husband at the Linwood Cemetery. In memory of Bickerdyke’s selflessness, a statue of her was erected in Galesburg, Illinois. Two ships…a hospital boat, a liberty ship, and a cemetery in Kansas were named after her.

Sea. When the war was over, she rode at the head of the XV Corps in the Grand Review in Washington at General William T. Sherman’s request. Afterwards, she worked for the Salvation Army in San Francisco, and became an attorney, helping Union veterans with legal issues. Later, she ran a hotel in Salina, Kansas for a time before retiring to Bunker Hill, Kansas. She received a special pension of $25 a month from Congress in 1886. She died peacefully after a minor stroke November 8, 1901. Her remains were transported back to Galesburg, Illinois and she was interred next to her husband at the Linwood Cemetery. In memory of Bickerdyke’s selflessness, a statue of her was erected in Galesburg, Illinois. Two ships…a hospital boat, a liberty ship, and a cemetery in Kansas were named after her.

Often we think that the best course of action is to simply attack a problem head on, but that is not always true, as Union General Ulysses S. Grant would find out on June 3, 1864. The United States was deep into the Civil War, and on that particular day, and the Confederate Army was entrenched at Cold Harbor, Virginia. General Grant was about to make the greatest mistakes of his career.

Often we think that the best course of action is to simply attack a problem head on, but that is not always true, as Union General Ulysses S. Grant would find out on June 3, 1864. The United States was deep into the Civil War, and on that particular day, and the Confederate Army was entrenched at Cold Harbor, Virginia. General Grant was about to make the greatest mistakes of his career.

Since the battle began on May 31st, Grant’s Army of the Potomac and Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had inflicted frightful losses upon each other as they worked their way around Richmond, Virginia…from the Wilderness forest to Spotsylvania and numerous smaller battle sites…the previous month. On May 30, Lee and Grant collided  at Bethesda Church. The next day the battle began when the advance units of the armies arrived at the crossroads of Cold Harbor, which was just 10 miles from Richmond, Virginia. There, a Yankee attack seized the intersection. Grant decided that this was the perfect chance to destroy Lee at the gates of Richmond, Grant prepared for a major assault along the entire Confederate front on June 2nd, but his plan was delayed because the necessary troops…Winfield Hancock’s Union corps did not arrive on schedule, the operation was delayed until the following day.

at Bethesda Church. The next day the battle began when the advance units of the armies arrived at the crossroads of Cold Harbor, which was just 10 miles from Richmond, Virginia. There, a Yankee attack seized the intersection. Grant decided that this was the perfect chance to destroy Lee at the gates of Richmond, Grant prepared for a major assault along the entire Confederate front on June 2nd, but his plan was delayed because the necessary troops…Winfield Hancock’s Union corps did not arrive on schedule, the operation was delayed until the following day.

The delay was a tragic move for the Union army, because it gave Lee’s troops time to entrench. Grant was frustrated with the prolonged pursuit of Lee’s army, so he gave the order to attack on June 3, but the entrenched Confederate army had the protection of deep trenches atop a hill, making the Union army have to attack without cover. It was a decision that resulted in a complete disaster. The Yankees were met with murderous fire, and were only able to reach the Confederate trenches in a few places. The 7,000 Union casualties, compared to only 1,500 for the Confederates, were all lost in under an hour. A dejected Grant pulled out of Cold Harbor nine days later and continued to try to flank Lee’s army. His next stop was Petersburg, south of Richmond, where he forced a nine-month siege. While Petersburg would redeem him some, there would be no more attacks on the scale of Cold Harbor.

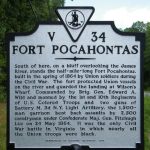

Prior to the Civil War, and even for years afterward, the black man was considered first a non-human, and secondly not very intelligent. Because of that, it was thought that the black soldiers would not be able to handle real combat situations. Nevertheless, the Union Army needed their help, and so they would have to take a chance on the black soldiers along the James River in the spring of 1864. My guess is that it was a rather tense moment when the Federal Soldiers faced off the Rebels on May 24, 1864. They stood behind the walls they had built with their own hands, and watched as the dismounted Rebel cavalry charged toward them. With their rifles trained on the enemy troops, each man knew that this was their chance to prove themselves. They were a brigade of mostly black soldiers, and it was vital that they be able to hold their own against an enemy who outnumbered them two to one. As well as an enemy who was party to their years of slavery.

Prior to the Civil War, and even for years afterward, the black man was considered first a non-human, and secondly not very intelligent. Because of that, it was thought that the black soldiers would not be able to handle real combat situations. Nevertheless, the Union Army needed their help, and so they would have to take a chance on the black soldiers along the James River in the spring of 1864. My guess is that it was a rather tense moment when the Federal Soldiers faced off the Rebels on May 24, 1864. They stood behind the walls they had built with their own hands, and watched as the dismounted Rebel cavalry charged toward them. With their rifles trained on the enemy troops, each man knew that this was their chance to prove themselves. They were a brigade of mostly black soldiers, and it was vital that they be able to hold their own against an enemy who outnumbered them two to one. As well as an enemy who was party to their years of slavery.

The battle the black troops were about to fight was a small part of Lieutenant General Ulysses S Grant’s Overland Campaign. The goal was to cripple the Confederate capital, and in doing so, bring down the Confederacy before the end of 1864. The Army of the James consisted of the X and XVIII Corps. About 40% of the army’s 33,000 men were black. Butler was confident his “colored troops” would do all the Union hoped and more, because he realized they viewed their service as a chance to gain rights they had never had before for themselves and for their families…making blacks free and equal to whites. Of course, fear of capture and a return to slavery, was a great motivator to win this battle and the war too. In early May, Butler and his army left Fort Monroe at the mouth of the James River and drove upriver toward Bermuda Hundred, about 14 miles south of Richmond. The general believed this was a better position to attack the capital from this strip of land, which lies at the point where the Appomattox River meets the James. From there, Butler’s forces could disable rail transportation south of Richmond and with it, communication between the capital and points south.

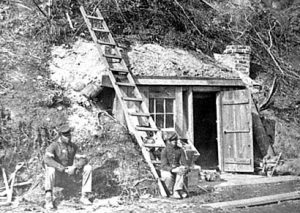

Late on the afternoon of May 5, a week before the army’s planned arrival on Bermuda Hundred, Butler reported to Grant that Brigadier General Edward A. Wild’s brigade of black troops had captured these two sites without opposition. Their arrival, Butler wrote, was “apparently a complete surprise” to the Confederates. The sight of former slaves coming ashore at Wilson’s Wharf must have almost terrified local planters, because many of the troops had once been held in bondage in the surrounding area. It could feel very intimidating to think of the former slaves motive for revenge. Shortly after the brigade’s arrival, the soldiers captured William Clopton, a wealthy planter known for his brutality. Wild, with his profound hatred of slavery, ordered his men to tie Clopton to a tree and expose his back. Then Wild ordered William Harris of Company E forward to flog his former master, Cheers echoed through the African Brigade. “Mr. Harris played his part conspicuously,” Sergeant Hatton recalled, “bringing the blood from his loins at every stroke, and not forgetting to remind the gentleman of the days gone by.” Wild described the lashing of Clopton to Hinks as “the administration of

Poetical justice.” The fears of the plantation owners were realized that day, but whipping the planters was the least of Wild’s concerns at Wilson’s Wharf. He immediately put his troops to work on an earthwork fortification on a bluff over the James and named it Fort Pocahontas. The walls held against Confederates, and the Union would go on to win the Civil War, but no one would again be able to say that the black soldiers couldn’t do their job, nor would they ever doubt the depth of their rage over the cruel treatment they had been subjected to by the slave owners.

Poetical justice.” The fears of the plantation owners were realized that day, but whipping the planters was the least of Wild’s concerns at Wilson’s Wharf. He immediately put his troops to work on an earthwork fortification on a bluff over the James and named it Fort Pocahontas. The walls held against Confederates, and the Union would go on to win the Civil War, but no one would again be able to say that the black soldiers couldn’t do their job, nor would they ever doubt the depth of their rage over the cruel treatment they had been subjected to by the slave owners.

In the year 1840, there was no such thing as the Fujita Scale, so when Natchez, Mississippi was hit by an F4 or F5 tornado on May 7, 1840, nobody knew its exact size, just that it was big…very big. Natchez in 1840 was a typical southern river town, reminiscent of the pre-Civil War days of slave labor and plantation wealth. Many people believed that nothing in their little part of the world could possibly change, and certainly not because of the weather. This was the context into which this tornado was about to enter…screaming violently.

In the year 1840, there was no such thing as the Fujita Scale, so when Natchez, Mississippi was hit by an F4 or F5 tornado on May 7, 1840, nobody knew its exact size, just that it was big…very big. Natchez in 1840 was a typical southern river town, reminiscent of the pre-Civil War days of slave labor and plantation wealth. Many people believed that nothing in their little part of the world could possibly change, and certainly not because of the weather. This was the context into which this tornado was about to enter…screaming violently.

May 7th started out hot and muggy, with overcast skies. The clouds were thick and most of that morning they produced continual rumblings of thunder. One resident recalled that the temperatures were in the mid-60s. Nothing about the day led anyone to believe that they were in eminent danger. And of course, at that time, there were no warning sirens, so the day dragged lazily along. At about 2 pm, the sky darkened so much that candles were needed to finish the mid-day meal that many were eating. The tornado touched down about 20 miles southwest of Natchez and moved in a northeasterly direction. It is believed that the tornado was rain-wrapped, because residence described it as “black masses, some stationary and some whirling” but the storm caused “no particular alarm” amongst the residents of Natchez. Most of the residents who weren’t eating dinner, were working down by the river. Dr Henry Tooley noted that the barometer began to fall rapidly, followed by the rain and then the tornado.

At about 2:10 pm the tornado screamed into Natchez. It lasted about three to five minutes, but the storm itself lasted about 30 minutes before it blew itself out of town. The damage path was about 10 miles long, and was estimated to be between one and two miles wide. For a time, it followed the Mississippi River hitting the southern and eastern edges of the town of Vidalia. Then the tornado crossed the river and continued on into Natchez. The town of Natchez was virtually wiped of the map, and the people on boats on the river were in serious trouble. Most of the boats on the river were flatboats, which were large rafts that carried goods on one-way trips down to New Orleans to be sold. Of the 120 flatboats docked at Natchez, 116 of them sunk. The unofficial estimated death toll was that as many as 200 people drowned after being tossed from their flatboats. It was said that “during the tornado the water rose between 10 and 15 feet, and that the water was whipped to such an extent where even a experienced swimmer could not sustain themselves on the surface.” There were also steamers one of which, The Prairie was ironically filled with a cargo of lead at the time. It sunk, of course. The steamer Hinds was badly damaged but did not sink. Its lifeless remains floated down the river to Baton Rouge where 51 bodies were found aboard.

It was really hard to establish an accurate death count, because most of the people on the river in Natchez  were not from Natchez. Most of the bodies that were found…those which were not lost after they floated out to sea…were unable to be identified because no-one knew who they were or where they came from. Lloyd’s Steamboat Disasters lists the number of lives lost that day at around 4004. In reality, this number was likely way off. This was a significant tornado, however damage also occurred above the river, in Natchez itself. The death toll may have also been skewed because in those days, the slaves were not always counted in census or death tolls. Either way, the Natchez tornado of 1840 ranks as the second most deadly tornado in US history, behind the Tri-State Tornado of 1925.

were not from Natchez. Most of the bodies that were found…those which were not lost after they floated out to sea…were unable to be identified because no-one knew who they were or where they came from. Lloyd’s Steamboat Disasters lists the number of lives lost that day at around 4004. In reality, this number was likely way off. This was a significant tornado, however damage also occurred above the river, in Natchez itself. The death toll may have also been skewed because in those days, the slaves were not always counted in census or death tolls. Either way, the Natchez tornado of 1840 ranks as the second most deadly tornado in US history, behind the Tri-State Tornado of 1925.

I think that anyone who has studied the Civil War, knows that it got started when the Confederates attacked Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861…officially anyway. Of course, the Civil War was all about slavery, and the North and South could not agree on the issue. As with all wars, there was some posturing before the war actually got started. Each side tries to scare the other into compliance, but sometimes that just doesn’t work out. The strange thing about the Civil War was that the “posturing stage” of the war ended up being a comedy of errors, when an inexperienced gunner accidently discharged his cannon into the fort on March 12, 1861. After the error, in which no one was hurt or killed, thankfully, the Confederates had to row over and apologize for the mistake. That strikes me as really funny, because everyone knew the war was coming, but just not when it would start.

I think that anyone who has studied the Civil War, knows that it got started when the Confederates attacked Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861…officially anyway. Of course, the Civil War was all about slavery, and the North and South could not agree on the issue. As with all wars, there was some posturing before the war actually got started. Each side tries to scare the other into compliance, but sometimes that just doesn’t work out. The strange thing about the Civil War was that the “posturing stage” of the war ended up being a comedy of errors, when an inexperienced gunner accidently discharged his cannon into the fort on March 12, 1861. After the error, in which no one was hurt or killed, thankfully, the Confederates had to row over and apologize for the mistake. That strikes me as really funny, because everyone knew the war was coming, but just not when it would start.

All that “practice” apparently didn’t help either, because when the war actually started, they fired over 3,000  shells at the fort without injuring a single Union soldier. Nevertheless, the men at the fort were apparently intimidated, because they surrendered and a Confederate officer named Roger Pryor rowed out to negotiate the terms. As the discussion progressed, Pryor casually got up, poured himself a glass of whiskey. Probably not the best idea. He downed it in one gulp, before finding out that it was actually a bottle of medical iodine that happened to be nearby. Pryor’s “Three Stooges” moment ended with army doctors frantically pumping his stomach while nervous Union officers wondered how they were going to explain poisoning the negotiator. I can see it all now. The Union doctors were scrambling to save Pryor’s life, all the while thinking that the Confederate soldiers were going to accuse them of trying to murder him. Fortunately, Pryor survived, but the comedy of errors did not end there. In what would become one last screw-up, and to mark the surrender, the Union commander ordered his gunners to fire a salute. Once again, the “training” given was lacking or the soldiers were just careless. The gunners piled cartridges next to

shells at the fort without injuring a single Union soldier. Nevertheless, the men at the fort were apparently intimidated, because they surrendered and a Confederate officer named Roger Pryor rowed out to negotiate the terms. As the discussion progressed, Pryor casually got up, poured himself a glass of whiskey. Probably not the best idea. He downed it in one gulp, before finding out that it was actually a bottle of medical iodine that happened to be nearby. Pryor’s “Three Stooges” moment ended with army doctors frantically pumping his stomach while nervous Union officers wondered how they were going to explain poisoning the negotiator. I can see it all now. The Union doctors were scrambling to save Pryor’s life, all the while thinking that the Confederate soldiers were going to accuse them of trying to murder him. Fortunately, Pryor survived, but the comedy of errors did not end there. In what would become one last screw-up, and to mark the surrender, the Union commander ordered his gunners to fire a salute. Once again, the “training” given was lacking or the soldiers were just careless. The gunners piled cartridges next to  their cannons…in a high wind. The resulting explosion killed two of their own men, the only casualties of the siege.

their cannons…in a high wind. The resulting explosion killed two of their own men, the only casualties of the siege.

The war had at least one other comedy of errors, this time in Congress. In 1858, tensions between pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions were so heated that a huge brawl broke out between at least 30 Congressmen on the House floor. This was not just an argument, it was a brawl, and it only came to an end when Mississippi’s William Barksdale had his wig knocked off. Since Barksdale never admitted to wearing a wig, he quickly snatched it back up and put it on inside out, causing everyone to stop fighting and start laughing instead. Barksdale didn’t think it funny, but I do.

These days, with all the television shows about secret agents, undercover cops, and spies, most of us wouldn’t think twice about one of those positions being held by a woman. During the American Civil War, however, which basically coincided with the Victorian era, one of the most morally repressive eras in history for women, things were different. Everything from a woman’s dress to her education were tightly constricted by moral attitudes that governed her every action. Basically, women were to concentrate their “war efforts” on the task of supporting their husband, brothers, or fathers, in whatever their beliefs were toward the matter. However, as the war dragged on and more men were called into active duty, the farms, factories, stores, and schools were left without workers, so the women stepped up to stand in the gap, as it were. This was most surprising because, back then, women were considered too frail, and their minds too simple for things like politics and war. They were designed for keeping the home and taking care of the babies. Nevertheless, when the men were called into active duty, most of them would have lost their farms, homes, and businesses had it not been for the strength and intelligence of the of the “frail and simple” women. Many women refused to limit their assistance to their country to what could be accomplished close to home. Some of them became nurses, worked to raise supplies for their troops, or even worked in armories, but there was a number of these women decided to support their country in a more dangerous…and scandalous way…they became spies.Back then, espionage was considered a very dishonorable pursuit for a man during the Civil War era, but for a woman…it was tantamount to prostitution. Nevertheless, with the war raging, women of both the North and South flaunted the Victorian morality of the time to provide their country the intelligence it needed to make tactical and practical decisions.

These days, with all the television shows about secret agents, undercover cops, and spies, most of us wouldn’t think twice about one of those positions being held by a woman. During the American Civil War, however, which basically coincided with the Victorian era, one of the most morally repressive eras in history for women, things were different. Everything from a woman’s dress to her education were tightly constricted by moral attitudes that governed her every action. Basically, women were to concentrate their “war efforts” on the task of supporting their husband, brothers, or fathers, in whatever their beliefs were toward the matter. However, as the war dragged on and more men were called into active duty, the farms, factories, stores, and schools were left without workers, so the women stepped up to stand in the gap, as it were. This was most surprising because, back then, women were considered too frail, and their minds too simple for things like politics and war. They were designed for keeping the home and taking care of the babies. Nevertheless, when the men were called into active duty, most of them would have lost their farms, homes, and businesses had it not been for the strength and intelligence of the of the “frail and simple” women. Many women refused to limit their assistance to their country to what could be accomplished close to home. Some of them became nurses, worked to raise supplies for their troops, or even worked in armories, but there was a number of these women decided to support their country in a more dangerous…and scandalous way…they became spies.Back then, espionage was considered a very dishonorable pursuit for a man during the Civil War era, but for a woman…it was tantamount to prostitution. Nevertheless, with the war raging, women of both the North and South flaunted the Victorian morality of the time to provide their country the intelligence it needed to make tactical and practical decisions.

The most famous of these female spies was Belle Boyd…born Marie Isabella Boyd. She began spying for the Confederacy when Union troops invaded her Martinsburg, Virginia home in 1861. One of the Federal soldiers manhandled her mother, and Boyd shot and killed him. She was exonerated in the soldier’s death, and an emboldened Boyd managed to befriend the Union soldiers left to guard her, and used her slave, Eliza, to pass information confided in her by the soldiers along to Confederate officers. Boyd was caught at her first attempt at spying, and threatened with death, but she did not stop her activities. She vowed to find a better way instead. She began eavesdropping on union officers staying at her father’s hotel. She learned enough to inform General Stonewall Jackson about their regiment and activities. Taking no chances, this time, Boyd delivered her intelligence firsthand, moving through Union lines, and reportedly drawing close enough to the action to return with bullet holes in her skirts. The information she provided allowed the Confederate army to advance on Federal troops at Fort Royal. Boyd’s daring acts of espionage soon caught up with her again and when a beau gave her up to Union authorities in 1862, she was arrested and held in the Old Capitol Prison in Washington for a month. Then she released, but found herself in the arrested again soon after. Once again, she managed to be set free, and this time she traveled to England, where amazingly, she married not a Confederate soldier, but a Union officer.

Boyd wasn’t the only spy in the Civil War. Another famous female spy was nicknamed “Crazy Bet,” but her real  name was Elizabeth Van Lew. Van Lew was born to a wealthy and prominent Richmond family, and was educated by Quakers in Philadelphia. When she returned to Richmond, she had become an abolitionist. She even went so far as to convince her mother to free the family’s slaves. Her espionage activity began soon after the start of the war. Her neighbors were appalled, because she openly supported the Union. She concentrated her efforts on aiding Federal prisoners at the Libby Prison, by taking them food, books, and paper. Later, she smuggled information about Confederate activities from the prisoners to Union officers, including General Ulysses S. Grant. To hide her activities from her Confederate neighbors, she behaved oddly. She dressed in old clothes, talking to herself, and refusing to comb her hair. Believe it or not, people began to think she was insane. They started calling her “Crazy Bet.” Van Lew wasn’t insane, in fact, she was incredibly intelligent. She was hailed by Grant as the provider of some of the most important intelligence gathered during the war.

name was Elizabeth Van Lew. Van Lew was born to a wealthy and prominent Richmond family, and was educated by Quakers in Philadelphia. When she returned to Richmond, she had become an abolitionist. She even went so far as to convince her mother to free the family’s slaves. Her espionage activity began soon after the start of the war. Her neighbors were appalled, because she openly supported the Union. She concentrated her efforts on aiding Federal prisoners at the Libby Prison, by taking them food, books, and paper. Later, she smuggled information about Confederate activities from the prisoners to Union officers, including General Ulysses S. Grant. To hide her activities from her Confederate neighbors, she behaved oddly. She dressed in old clothes, talking to herself, and refusing to comb her hair. Believe it or not, people began to think she was insane. They started calling her “Crazy Bet.” Van Lew wasn’t insane, in fact, she was incredibly intelligent. She was hailed by Grant as the provider of some of the most important intelligence gathered during the war.

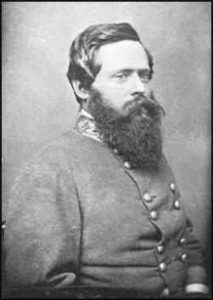

Captain George Hollins joined the United States Navy when he was just 15 years old, and served during the War of 1812. His was a long and distinguished career, but when the Civil War broke out in 1861, he chose to resign his commission, and offer his services to the Confederacy. After a brief stop in his hometown, Baltimore, Hollins offered his services to the Confederacy and received a commission on June 21, 1861. I suppose that every man had to choose a side in the Civil War, and I’m sure he considered his reasons for choosing the Confederacy to be valid, but many of us would consider his actions to be almost traitorous, were it not for the fact that both sides were the United States…just not so united.

Captain George Hollins joined the United States Navy when he was just 15 years old, and served during the War of 1812. His was a long and distinguished career, but when the Civil War broke out in 1861, he chose to resign his commission, and offer his services to the Confederacy. After a brief stop in his hometown, Baltimore, Hollins offered his services to the Confederacy and received a commission on June 21, 1861. I suppose that every man had to choose a side in the Civil War, and I’m sure he considered his reasons for choosing the Confederacy to be valid, but many of us would consider his actions to be almost traitorous, were it not for the fact that both sides were the United States…just not so united.

Hollins devised a plan to capture a commercial vessel that was bringing supplies to the Union Army. Then they planned to use that ship to lure other Union ships into Confederate service. Soon after, Hollins met up with Richard Thomas Zarvona, a fellow Marylander and former student at West Point. Zarvona  was an adventurer who had fought with pirates in China and revolutionaries in Italy. He seemed the perfect co-conspirator for this project. They devised a plan to capture the Saint Nicholas. Then it would be the decoy they used to force other Yankee ships into Confederate service. Zarvona went to Baltimore,where he recruited a band of pirates, who boarded the Saint Nicholas as paying passengers on June 28, 1862. Using the name Madame La Force, Zarvona disguised himself as a flirtatious French woman. Hollins boarded the Saint Nicholas at its first stop.

was an adventurer who had fought with pirates in China and revolutionaries in Italy. He seemed the perfect co-conspirator for this project. They devised a plan to capture the Saint Nicholas. Then it would be the decoy they used to force other Yankee ships into Confederate service. Zarvona went to Baltimore,where he recruited a band of pirates, who boarded the Saint Nicholas as paying passengers on June 28, 1862. Using the name Madame La Force, Zarvona disguised himself as a flirtatious French woman. Hollins boarded the Saint Nicholas at its first stop.

A while later the band of co-conspirators went to the “French woman’s” cabin. Inside, they armed themselves and came back out on the deck to surprise the crew. After  capturing the crew, Hollins took control of the ship. At this point, the purpose of their mission began. They had planned to capture a Union gunboat, the Pawnee, but it was called away. Instead, the Saint Nicholas and its pirate crew came upon a ship loaded with Brazilian coffee, and two more ships, carrying loads of ice and coal. Both ships quickly fell to the Saint Nicholas. For his actions, Hollins received a promotion to commodore and was sent to New Orleans to command the naval forces there at the end of July. On July 8, he would try another daring mission, to capture the Columbia, a sister ship of the Saint Nicholas, but the captain of the Saint Nicholas was on board the Columbia, on his way home after being released by the Confederate authorities. He recognized the men and they were arrested. It was the end of his tirade.

capturing the crew, Hollins took control of the ship. At this point, the purpose of their mission began. They had planned to capture a Union gunboat, the Pawnee, but it was called away. Instead, the Saint Nicholas and its pirate crew came upon a ship loaded with Brazilian coffee, and two more ships, carrying loads of ice and coal. Both ships quickly fell to the Saint Nicholas. For his actions, Hollins received a promotion to commodore and was sent to New Orleans to command the naval forces there at the end of July. On July 8, he would try another daring mission, to capture the Columbia, a sister ship of the Saint Nicholas, but the captain of the Saint Nicholas was on board the Columbia, on his way home after being released by the Confederate authorities. He recognized the men and they were arrested. It was the end of his tirade.

During the Civil War, rail lines were crucial for moving supplies from one place to another. The different sides often tried to waylay the trains, derail the trains, or even destroy the rails. On June 10, 1864, a Confederate cavalry intercepted General Phillip Sheridan’s Union cavalry while they were trying to destroy a rail line near Trevilian Station, Virginia. The ensuing battle lasted two days before the Confederates were finally able to drive off the Union cavalry from the station, with minimal damage to a precious supply line.

During the Civil War, rail lines were crucial for moving supplies from one place to another. The different sides often tried to waylay the trains, derail the trains, or even destroy the rails. On June 10, 1864, a Confederate cavalry intercepted General Phillip Sheridan’s Union cavalry while they were trying to destroy a rail line near Trevilian Station, Virginia. The ensuing battle lasted two days before the Confederates were finally able to drive off the Union cavalry from the station, with minimal damage to a precious supply line.

After the Confederate victory at the Battle of Cold Harbor in June 1864, in which over 15,000 combined casualties fell during the nearly two-week fight, Union General Ulysses S. Grant dispatched his cavalry commander, General Phillip Sheridan to ride towards Charlottesville and cut the Virginia Central Railroad. The line was supplying Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Lee’s Army was engaged in a life-or-death struggle with Grant’s Army of the Potomac, in the areas of Richmond and Petersburg.

Sheridan turned north to skirt around Richmond and headed toward Charlottesville, which was 60 miles northwest of Richmond. Unfortunately, Sheridan’s move was far from secret, and General Wade Hampton, commander of the Confederate cavalry, set out to intercept the Union cavalry. On the morning of June 11, Union General George Custer’s men attacked Hampton’s supply train near Trevilian Station. Although they scored an initial success, Custer soon found himself almost completely surrounded by the Confederate Cavalry. Custer formed his men into a triangle and made several counterattacks before Sheridan came to his rescue in the late afternoon, taking 500 Southern prisoners in the process.

The struggle continued the next day. With his ammunition running low and his cavalry dangerously far from its supply line, Sheridan eventually withdrew his force and returned to the Army of the Potomac. The Union Cavalry tore up about five miles of rail line, but the damage was relatively light for the high number of casualties. Sheridan lost 735 men compared with nearly 1,000 for Hampton. But the Confederates had driven off the Union cavalry and had kept the damage to railroad to a minimum…not that it would make a difference in the outcome of the Civil War.