canada

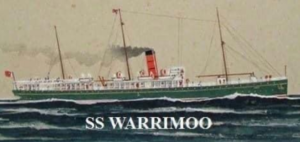

Sometimes, there can be a rare phenomenon that happens by chance, but unlike the phenomenon of twins being born on different days, the phenomenon that took place on December 31, 1899, while not totally planned, had to be helped just a little bit. On that night, the last night of the year, the passenger steamer, SS Warrimoo was quietly making its way through the dark waters of the mid Pacific Ocean on its way from Vancouver, Canada to Australia. In the days without GPS, the navigation was calculated by the stars. It was very accurate. That night, the navigator had just finished working out a star fix and brought the results to Captain John DS Phillips. The Warrimoo’s position was LAT 0º 31′ N and LONG 179 30′ W. The date was December 31, 1899. First mate Payton broke in saying, “Know what this means? We’re only a few miles from the intersection of the Equator and the International Date Line.” At first thought many of us would not see the significance of that, but Captain Phillips saw it, and he was just “prankish” enough to take full advantage of the opportunity for achieving the “navigational freak of a lifetime.”

Sometimes, there can be a rare phenomenon that happens by chance, but unlike the phenomenon of twins being born on different days, the phenomenon that took place on December 31, 1899, while not totally planned, had to be helped just a little bit. On that night, the last night of the year, the passenger steamer, SS Warrimoo was quietly making its way through the dark waters of the mid Pacific Ocean on its way from Vancouver, Canada to Australia. In the days without GPS, the navigation was calculated by the stars. It was very accurate. That night, the navigator had just finished working out a star fix and brought the results to Captain John DS Phillips. The Warrimoo’s position was LAT 0º 31′ N and LONG 179 30′ W. The date was December 31, 1899. First mate Payton broke in saying, “Know what this means? We’re only a few miles from the intersection of the Equator and the International Date Line.” At first thought many of us would not see the significance of that, but Captain Phillips saw it, and he was just “prankish” enough to take full advantage of the opportunity for achieving the “navigational freak of a lifetime.”

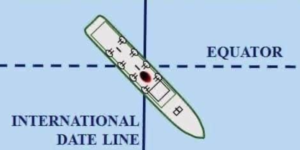

Phillips called his navigators to the bridge to check and double check the ship’s position. It simply would not do for there to be any miscalculation. He changed course slightly so as to bear directly on his mark. Then, he adjusted the engine speed for perfect timing. The calm weather and clear night worked in his favor. With determined and careful maneuvering, the SS Warrimoo was in perfect position at midnight. The ship now sat on the Equator at exactly the point where it crossed the International Date Line! This seems like a minor thing, but  the consequences of this bizarre position were actually many. This put the forward part (bow) of the ship was in the Southern Hemisphere and in the middle of summer; the rear (stern) was in the Northern Hemisphere and in the middle of winter; the date in the aft part of the ship was December 31, 1899; in the bow (forward) part it was January 1, 1900. They had managed to place the ship not only in two different days, two different months, two different years, and two different seasons…but, in two different centuries…all at the same time!! Amazing, and unlikely to ever happen again, unless it was specifically planned.

the consequences of this bizarre position were actually many. This put the forward part (bow) of the ship was in the Southern Hemisphere and in the middle of summer; the rear (stern) was in the Northern Hemisphere and in the middle of winter; the date in the aft part of the ship was December 31, 1899; in the bow (forward) part it was January 1, 1900. They had managed to place the ship not only in two different days, two different months, two different years, and two different seasons…but, in two different centuries…all at the same time!! Amazing, and unlikely to ever happen again, unless it was specifically planned.

Every time an airplane crashes, we expect the worst…multiple deaths, if not the death of everyone on board. Some crashes look so horrific that you wonder how anyone could possibly have lived. While dropping from the sky to land on the hard ground or even on water usually ends in devastation, once in a while, a miracle happens, and everyone on the plane walks away from the crash…everyone!! It can only be called a miracle crash.

Every time an airplane crashes, we expect the worst…multiple deaths, if not the death of everyone on board. Some crashes look so horrific that you wonder how anyone could possibly have lived. While dropping from the sky to land on the hard ground or even on water usually ends in devastation, once in a while, a miracle happens, and everyone on the plane walks away from the crash…everyone!! It can only be called a miracle crash.

These days, probably the most well-known “miracle crash” was the “Miracle on the Hudson” crash. Captain Sullenberger was an amazing pilot, and as a result, all 155 people walked away from what could have been a horrible crash. Some pilots might have even tried to make it back to the airport, flying over and crashing into the city buildings, but “Sully” knew that was impossible, so he did the only sensible thing and water landed into the Hudson River.

There have been a number of other “miracle crashes” throughout the history of aviation. Some in small planes,  but some in large commercial planes. It may not always be possible, but a good pilot has a much better chance of landing, or really crashing their airplane and being so successful at it, that everyone walks away. The passengers are likely to have a few injuries, but they are alive, and that is what matters.

but some in large commercial planes. It may not always be possible, but a good pilot has a much better chance of landing, or really crashing their airplane and being so successful at it, that everyone walks away. The passengers are likely to have a few injuries, but they are alive, and that is what matters.

German photographer Dietmar Eckell has made it his life’s work to find, what he calls “miracles in aviation history” at the abandoned sites of wrecks that have resulted in no casualties. Eckell’s photo-project, “Happy End” highlights 15 airplanes that had forced landings, in which all the people on board survived and were rescued from really remote locations. One thing I don’t always understand is that the planes are abandoned where they crashed. I suppose sometimes it is hard to recover them, and other times they have already been there for years, by the time they are located. I never knew how many planes litter the earth, both above and below the water, but there are many.

Two of the “miracle crashes” that Eckell photographed were the Douglas Skytrain C-47 that crashed in the  Yukon in Canada in February 1950 and the Avro Shackleton, that crashed in the Western Sahara in 1994. In the crash of the Douglas Skytrain, all 10 people aboard survived, even in the frigid conditions. With the Avro Shackleton, two engines of the plane suddenly failed, sending it down to the desert sand in 1994. Surviving this crash in such an inhospitable environment was an astonishing feat for the 19 passengers and crew. If it weren’t for Dietmar Eckell’s determination to search out and photograph these lost “miracle crash” sites, much of the history of these miracles might have been forgotten. I for one plane to look up his “Happy End” project to read more about the “miracle crashes” he found.

Yukon in Canada in February 1950 and the Avro Shackleton, that crashed in the Western Sahara in 1994. In the crash of the Douglas Skytrain, all 10 people aboard survived, even in the frigid conditions. With the Avro Shackleton, two engines of the plane suddenly failed, sending it down to the desert sand in 1994. Surviving this crash in such an inhospitable environment was an astonishing feat for the 19 passengers and crew. If it weren’t for Dietmar Eckell’s determination to search out and photograph these lost “miracle crash” sites, much of the history of these miracles might have been forgotten. I for one plane to look up his “Happy End” project to read more about the “miracle crashes” he found.

When we think of a cowboy, we usually picture the American Cowboy, rough and rugged wearing a cowboy hat, a gun on his hip, and riding he favorite horse around the Old West. One thing we wouldn’t think of is that we really wouldn’t think of an American Cowboy being born in Canada. Nevertheless, one of the most “unusual” American Cowboys was actually born in Canada. His name was Charles Nebo, or as he was known by nickname, Charley, and he was born in March of 1842. Charles Nebo wasn’t your typical cowboy and might have even been more Forrest Gump than soldier, although he wasn’t autistic, like Forrest Gump was…or at least, not that anyone knew of.

When we think of a cowboy, we usually picture the American Cowboy, rough and rugged wearing a cowboy hat, a gun on his hip, and riding he favorite horse around the Old West. One thing we wouldn’t think of is that we really wouldn’t think of an American Cowboy being born in Canada. Nevertheless, one of the most “unusual” American Cowboys was actually born in Canada. His name was Charles Nebo, or as he was known by nickname, Charley, and he was born in March of 1842. Charles Nebo wasn’t your typical cowboy and might have even been more Forrest Gump than soldier, although he wasn’t autistic, like Forrest Gump was…or at least, not that anyone knew of.

Charlie never tried to inflate his achievements and was happy to live like a true frontier man, nevertheless, people often made him sound like he was…maybe, a little bit more of a cowboy than he actually was. I suppose it made no sense to say that he was just a “good old boy” from out west. People don’t expect that, and maybe, they just wouldn’t read about it, either, but the reality is that there were more average people in the American West than there were the wild people who made the West famous.

Charley Nebo lived in Canada until 1861. Then, he moved to Saginaw, Michigan. He was a Union soldier during the Civil War and went on to become a cowboy in New Mexico. At one point he actually befriended Billy the Kid. Nebo wrote about him in a letter, saying, “He wasn’t the ruthless bad fellow that Western history has made him out to be.” Nebo apparently gave people the benefit of the doubt, and himself, as a respected cowboy, once shot a man after witnessing him kill a Mexican boy’s dog. In all, Nebo was a common man, humble and capable. He wasn’t what people might call spectacular, but he was a good man, and it took a lot of those good men to build the American West.

In order to support a hurricane or typhoon, an area has to have one ingredient…warm ocean temperatures, generally above 82° F. The warm water sustains hurricanes and allows them to grow stronger. On the other hand, cooler sea surface temperatures will cause hurricanes to weaken, and in most cases, die out. The biggest difference between the East and West coasts of the United States are the sea surface temperatures. Because the Gulf Stream flows northwards along the East Coast, while sea surface temperatures along the West Coast are significantly cooler, the West Coast cannot usually sustain hurricanes. Of course, that doesn’t mean that it is impossible, as is shown in the 1962 Columbus Day Storm…also called the Big Blow and in Canada, Typhoon Freda.

In order to support a hurricane or typhoon, an area has to have one ingredient…warm ocean temperatures, generally above 82° F. The warm water sustains hurricanes and allows them to grow stronger. On the other hand, cooler sea surface temperatures will cause hurricanes to weaken, and in most cases, die out. The biggest difference between the East and West coasts of the United States are the sea surface temperatures. Because the Gulf Stream flows northwards along the East Coast, while sea surface temperatures along the West Coast are significantly cooler, the West Coast cannot usually sustain hurricanes. Of course, that doesn’t mean that it is impossible, as is shown in the 1962 Columbus Day Storm…also called the Big Blow and in Canada, Typhoon Freda.

The Columbus Day Storm was a Pacific Northwest windstorm that struck the West Coast of Canada and the Pacific Northwest coast of the United States on October 12, 1962. Starting out as a tropical disturbance over the Northwest Pacific on September 28th, the storm was the twenty-eighth tropical depression, the twenty-third tropical storm, and the eighteenth typhoon of the 1962 Pacific typhoon season. The system strengthened on October 3rd and became a tropical storm. At that time, it was given the name Freda, but later that day it became a typhoon as it moved northeastward. Before long the storm intensified, reaching its peak as a Category 3-equivalent typhoon on October 5th, with maximum 1-minute sustained winds of 115 mph and a minimum central pressure of 948 millibars. The storm maintained its intensity for another day, and then gradually weakened on October 6th. By October 9th, Freda had weakened into a tropical storm, and it looked

like the Pacific Northwest would dodge a bullet. Then Freda transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on October 10th. Freda turned eastward and accelerated across the North Pacific on October 11th, and finally made before striking the Pacific Northwest the next day. On October 13th, the cyclone made landfall on Washington and Vancouver Island, and then curved northwestward. After ripping through the west coast of the Washington and Canada, the system moved inland in Canada and weakened. By October 17th, it was absorbed by another developing storm to the south, and the event was over.

like the Pacific Northwest would dodge a bullet. Then Freda transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on October 10th. Freda turned eastward and accelerated across the North Pacific on October 11th, and finally made before striking the Pacific Northwest the next day. On October 13th, the cyclone made landfall on Washington and Vancouver Island, and then curved northwestward. After ripping through the west coast of the Washington and Canada, the system moved inland in Canada and weakened. By October 17th, it was absorbed by another developing storm to the south, and the event was over.

Nevertheless, the Columbus Day Storm of 1962 is considered to be the benchmark of extratropical windstorms to this day. As storm ranking goes, the Columbus Day Storm is listed as being among the most intense to strike the region since at least 1948, and quite likely since the January 9, 1880 “Great Gale” and snowstorm. With respect to wind velocity, the storm is also considered a contender for the title of the most powerful extratropical cyclone recorded in the United States in the 20th century. Even the March 1993 “Storm of the Century” and the “1991 Halloween Nor’easter” (“The Perfect Storm”) were no match. The system that drove the Columbus Day Storm brought strong winds to the Pacific Northwest and southwest Canada, was linked to 46 fatalities in the northwest and Northern California as a result of heavy rains and mudslides.

Normally, the storms that originate in the Pacific tend to weaken and die out as they reach the colder waters there. most don’t even recurve into the west coast after the leave the warmer gulf waters and head across Mexico. That is what made the Columbus Day storm so unusual for the area in which it took place.

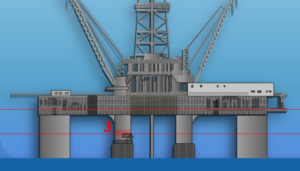

Over the years, we have gotten used to seeing offshore drilling rigs in the oceans surrounding our country, and other countries too, I’m sure. Generally, these rigs are safe places to work, but it’s hard to guarantee safety in some of the fierce storms that occur around the globe. Ocean Ranger was a semi-submersible mobile offshore drilling unit that was located 166 miles east of Saint John’s, Newfoundland. Ocean Ranger was designed and owned by Ocean Drilling and Exploration Company Inc (ODECO) of New Orleans. Ocean Ranger was actually a self-propelled large semi-submersible vessel, designed with a drilling facility and living quarters. It was capable of operation beneath 1,500 feet of ocean water and could drill to a maximum depth of 25,000 feet. At the time of its launch, it was described by ODECO as the world’s largest semi-submersible oil rig to date.

Over the years, we have gotten used to seeing offshore drilling rigs in the oceans surrounding our country, and other countries too, I’m sure. Generally, these rigs are safe places to work, but it’s hard to guarantee safety in some of the fierce storms that occur around the globe. Ocean Ranger was a semi-submersible mobile offshore drilling unit that was located 166 miles east of Saint John’s, Newfoundland. Ocean Ranger was designed and owned by Ocean Drilling and Exploration Company Inc (ODECO) of New Orleans. Ocean Ranger was actually a self-propelled large semi-submersible vessel, designed with a drilling facility and living quarters. It was capable of operation beneath 1,500 feet of ocean water and could drill to a maximum depth of 25,000 feet. At the time of its launch, it was described by ODECO as the world’s largest semi-submersible oil rig to date.

Ocean Ranger was constructed for ODECO in 1976 by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in Hiroshima, Japan. It was 396 feet long, 262 feet wide, and 337 feet high. It had twelve 45,000-pound anchors. The weight was 25,000 tons. It was floating on two 400-foot-long pontoons that rested 79 feet below the surface. It was massive and very impressive, and it was approved for “unrestricted ocean operations.” Prior to moving to the Grand Banks area in November 1980, it had operated off the coasts of Alaska, New Jersey and Ireland.

On November 26, 1981, Ocean Ranger commenced drilling well J-34, its third well in the Hibernia Oil Field. Ocean Ranger was still working on this well in February 1982 when the incident occurred. Ocean Ranger was designed to withstand extremely harsh conditions at sea, including 100-knot winds and 110-foot waves, but the  storm off of Canada on February 14, 1982, would prove to be too much for it. Two other semi-submersible platforms were drilling nearby Ocean Ranger on that fateful day. Sedco 706 was 8.5 miles NNE, and Zapata Ugland was 19.2 miles N of Ocean Ranger. On February 14, 1982, the platforms received reports of an approaching storm linked to a major Atlantic cyclone from NORDCO Ltd, the company responsible for issuing offshore weather forecasts. There were protocols in place, and the crew began preparing for bad weather. They began hanging-off the drill pipe at the sub-sea wellhead and disconnecting the riser from the sub-sea blowout preventer. They worked hard, but due to surface difficulties and the speed at which the storm developed, the crew of Ocean Ranger were forced to shear the drill pipe after hanging-off, after which they disconnected the riser in the early evening.

storm off of Canada on February 14, 1982, would prove to be too much for it. Two other semi-submersible platforms were drilling nearby Ocean Ranger on that fateful day. Sedco 706 was 8.5 miles NNE, and Zapata Ugland was 19.2 miles N of Ocean Ranger. On February 14, 1982, the platforms received reports of an approaching storm linked to a major Atlantic cyclone from NORDCO Ltd, the company responsible for issuing offshore weather forecasts. There were protocols in place, and the crew began preparing for bad weather. They began hanging-off the drill pipe at the sub-sea wellhead and disconnecting the riser from the sub-sea blowout preventer. They worked hard, but due to surface difficulties and the speed at which the storm developed, the crew of Ocean Ranger were forced to shear the drill pipe after hanging-off, after which they disconnected the riser in the early evening.

A Mayday call was sent out from Ocean Ranger at 12:52am local time, on February 15th, noting a severe list to the port side of the rig and requesting immediate assistance. This was the first communication from Ocean Ranger identifying a major problem. The standby vessel, the M/V Sea-forth Highlander, was requested to come in close, because countermeasures against the 10–15-degree list weren’t working. The onshore MOCAN supervisor was notified of the situation, and the Canadian Forces and Mobil-operated helicopters were alerted just after 1:00 local time. The M/V Boltentor and the M/V Nordertor, the standby boats of Sedco 706 and Zapata Ugland respectively, were also dispatched to Ocean Ranger to provide assistance. Everything happened so fast, and at 1:30am local time, Ocean Ranger transmitted its last message: “There will be no further radio communications from Ocean Ranger. We are going to lifeboat stations.” Shortly thereafter, in the middle of the  night and in the midst of that severe winter storm, the crew abandoned the platform. The platform remained afloat for another ninety minutes, sinking between 3:07am and 3:13am local time. All of Ocean Ranger sank beneath the Atlantic and by the next morning only a few buoys remained. Her entire crew of 84 workers…46 Mobil employees and 38 contractors from various service companies…were killed. There was evidence on at least one lifeboat launched with about 36 people onboard, but they didn’t survive either. Over the next week, 22 bodies were recovered from the North Atlantic. Autopsies indicated that those men had died as a result of drowning while in a hypothermic state.

night and in the midst of that severe winter storm, the crew abandoned the platform. The platform remained afloat for another ninety minutes, sinking between 3:07am and 3:13am local time. All of Ocean Ranger sank beneath the Atlantic and by the next morning only a few buoys remained. Her entire crew of 84 workers…46 Mobil employees and 38 contractors from various service companies…were killed. There was evidence on at least one lifeboat launched with about 36 people onboard, but they didn’t survive either. Over the next week, 22 bodies were recovered from the North Atlantic. Autopsies indicated that those men had died as a result of drowning while in a hypothermic state.

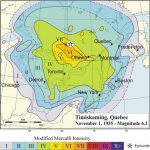

I suppose that if I lived in Quebec, Canada, I might have heard the Abitibi-Témiscamingue region and maybe even the Western Quebec Seismic Zone. Since I don’t, these areas are new to me. Maybe they were new to a lot of people, but on November 1, 1935, a lot more people knew about them. On that day, a 6.1 magnitude earthquake with a maximum Mercalli intensity of VII (Very strong) occurred. The epicenter occurred on a thrust fault in the Timiskaming Graben, a little over 6 miles northeast of Témiscamingue, at about 1:03am ET.

I suppose that if I lived in Quebec, Canada, I might have heard the Abitibi-Témiscamingue region and maybe even the Western Quebec Seismic Zone. Since I don’t, these areas are new to me. Maybe they were new to a lot of people, but on November 1, 1935, a lot more people knew about them. On that day, a 6.1 magnitude earthquake with a maximum Mercalli intensity of VII (Very strong) occurred. The epicenter occurred on a thrust fault in the Timiskaming Graben, a little over 6 miles northeast of Témiscamingue, at about 1:03am ET.

While the earthquake was in Canada, it was felt over a wide area of North America, extending west to Fort William (now Thunder Bay), east to Fredericton, New Brunswick, north to James Bay and south as far as Kentucky and West Virginia. Occasional aftershocks were reported for several months. That seems extreme for a 6.1 magnitude earthquake, but I suppose it’s all in the connections. Fault lines aren’t just in a small area, they run for hundreds and even thousands of miles.

The most significant damage from the earthquake, both in the immediate area and as far south as North Bay and Mattawa, was to chimneys. In fact, 80% of the chimneys in that area were destroyed. A railroad embankment near Parent, which is 186 miles away, also collapsed. It looked like the embankment slide was already imminent, but the quake vibrated the last holds loose. There were some rockfalls and structural cracks reported as well. Thankfully, there were few major structural collapses aside from the Parent embankment. The

sparseness of the area’s population played a big part in the relative lack of major damage, despite the fact that it was a strong earthquake. The water of Tee Lake, close to the epicenter was discolored by the earthquake…due to a stirring up of gyttja, which is freshwater mud with abundant organic matter, rather than silt input from tributary streams. The relative lack of major damage, despite the fact that it was a strong earthquake, has been attributed primarily to the sparseness of the area’s population.

sparseness of the area’s population played a big part in the relative lack of major damage, despite the fact that it was a strong earthquake. The water of Tee Lake, close to the epicenter was discolored by the earthquake…due to a stirring up of gyttja, which is freshwater mud with abundant organic matter, rather than silt input from tributary streams. The relative lack of major damage, despite the fact that it was a strong earthquake, has been attributed primarily to the sparseness of the area’s population.

When I think of a hurricane, I think of a tropical storm that escalates, and I suppose most of the time, that would be right, but it isn’t always the case. Sometimes hurricanes can develop in a more northern area, or as in the case of Hurricane Hazel on October 15, 1954 a strong hurricane somehow continues north as a hurricane after it hit first in a more southern area. Hurricane Hazel was a hurricane that struck the Carolina’s, and then and then moved into Ontario as a powerful extratropical storm…still of hurricane intensity, after that initial strike in the Carolinas.

When I think of a hurricane, I think of a tropical storm that escalates, and I suppose most of the time, that would be right, but it isn’t always the case. Sometimes hurricanes can develop in a more northern area, or as in the case of Hurricane Hazel on October 15, 1954 a strong hurricane somehow continues north as a hurricane after it hit first in a more southern area. Hurricane Hazel was a hurricane that struck the Carolina’s, and then and then moved into Ontario as a powerful extratropical storm…still of hurricane intensity, after that initial strike in the Carolinas.

The deadliest hurricane of the 1954 Atlantic hurricane season, Hurricane Hazel was also the second costliest, and the most intense hurricane of that year. The storm killed at least 469 people in Haiti before striking the United States as a Category 4 hurricane near the border between North and South Carolina. As Hazel ripped through Haiti, it destroyed 40% of the coffee trees and 50% of the cacao crop, which would drastically affected the economy for several years.

After causing 95 fatalities in the US, Hazel struck Canada as an extratropical storm, raising the death toll by 81 people, mostly in Toronto. When Hazel made landfall near Calabash, North Carolina, it destroyed most waterfront homes. Then as it screamed north along the Atlantic coast, Hazel affected Virginia, Washington DC, West Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and New York; as it lashed the area with gusts near 100 miles per hour and caused $281 million, which today would be $2720 million in damage. When it was over Pennsylvania, Hazel consolidated with a cold front and turned northwest towards Canada.

In addition to the fatalities, Hurricane Hazel brought with it flash flooding in Canada, which destroyed twenty bridges, killed 81 people, and left over 2,000 families homeless in Canada alone. In all, and including the strike in the Carolinas, where Hazel killed 95 people and caused almost $630 million ($6,100 million today) in damages, on top of over 500 other deaths and billions in damage in the US and Caribbean. No other recent natural disaster on Canadian soil has been so deadly. Floods killed 35 people on a single street in Toronto.

When it hit Ontario as an extratropical storm, rivers and streams in and around Toronto overflowed their banks, which caused severe flooding. As a result, many residential areas in the local floodplains, such as the Raymore Drive area, were subsequently converted to parkland. In Canada alone, over C$135 million (C$1.3 billion, 2021) of damage was incurred. The effects of Hazel were particularly unprecedented in Toronto due to a combination of heavy rainfall during the preceding weeks, a lack of experience in dealing with tropical storms,

and the storm’s unexpected retention of power despite traveling 680 miles over land. The storm stalled over the Toronto area, and although it was now extratropical, it remained as powerful as a category 1 hurricane. To help with the cleanup, 800 members of the military were called in and a Hurricane Relief Fund was quickly established that distributed $5.1 million ($49.1 million today) in aid. The name Hazel was retired as a named storm, because of the high death toll.

and the storm’s unexpected retention of power despite traveling 680 miles over land. The storm stalled over the Toronto area, and although it was now extratropical, it remained as powerful as a category 1 hurricane. To help with the cleanup, 800 members of the military were called in and a Hurricane Relief Fund was quickly established that distributed $5.1 million ($49.1 million today) in aid. The name Hazel was retired as a named storm, because of the high death toll.

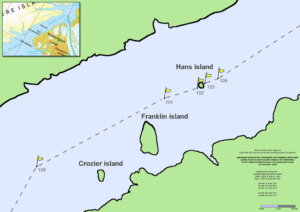

Hans Island is a desolate little rock of an island locate near Greenland in the center of what is known as the Kennedy Channel of Nares Strait. This is the strait that separates Ellesmere Island from northern Greenland and connects Baffin Bay with the Lincoln Sea. The island is barren and uninhabited, measuring 0.5 square mile, 4,230 feet long and 3,934 feet wide. Hans Island is the smallest of three islands in Kennedy Channel off the Washington Land coast; the others are Franklin Island and Crozier Island. The strait at this point is 22 miles wide, placing the island within the territorial waters of both Canada and Greenland (Denmark). Technically, a line in the middle of the strait goes through the island.

Hans Island is a desolate little rock of an island locate near Greenland in the center of what is known as the Kennedy Channel of Nares Strait. This is the strait that separates Ellesmere Island from northern Greenland and connects Baffin Bay with the Lincoln Sea. The island is barren and uninhabited, measuring 0.5 square mile, 4,230 feet long and 3,934 feet wide. Hans Island is the smallest of three islands in Kennedy Channel off the Washington Land coast; the others are Franklin Island and Crozier Island. The strait at this point is 22 miles wide, placing the island within the territorial waters of both Canada and Greenland (Denmark). Technically, a line in the middle of the strait goes through the island.

Most people would look at this island and say, “Ok, it is technically half Canadian and half Greenland (Denmark), but seriously, who cares?” It is a piece of rock that has no value, so there it is and nobody cares. The problem is that…oddly, both sides care…a great deal. You might be wondering why, at this point. Well, you would not be alone. I am wondering why too. For some reason, Canada and Denmark have been…well, playfully fighting over the control of this little piece of ground. Every so often, when officials from each country visit, they leave a bottle of their country’s liquor as a…power move. It really makes no sense. The island has no reserves of oil or natural gas, or anything else that would make it valuable, and yet it is the subject of an ongoing territorial dispute between Denmark and Canada over who owns this little rock…and it’s such an odd dispute at that. It will barely increase the respective countries’ land mass and yet they continue to “fight” over it.

Unlike many other territory conflicts, this one is fought in a markedly peaceful way. The potential serious diplomatic implications aside, the Canadians and Danes take turns placing their flags on the island. This curious practice that has been going on since the 1980s. But it gets even odder. The island was first disputed in 1933, but largely forgotten during World War II. The unusual dispute began again in earnest in 1984 when, during a visit to the island, the Danish Minister for Greenland planted the national flag and left a message saying “Welcome to the Danish island” (“Velkommen til den danske ø” in Danish) along with (it is said) a bottle of brandy. Ever since then, when the flag on the island is periodically changed between the Danish and Canadian flag, the bottle is also replaced. The Canadians leave a bottle of Canadian Club and the Danes a bottle of schnapps.

While the conflict is “lighthearted,” it is really a serious conflict, and remains unresolved today. At one point, it looked like they might have a solution. On May 4, 2008, an international group of scientists from Australia, Canada, Denmark, and the UK installed an automated weather station on Hans Island. To me that makes the most sense. Just share the island or let it be considered international. That isn’t exactly what happened, however. There were a number of people who think that there might be some minerals on Hans Island, making  it a possible valuable island after all…and renewing the conflict. Oh boy, here we go again.

it a possible valuable island after all…and renewing the conflict. Oh boy, here we go again.

The conflict is as of today still unresolved, but there are suggestions on how to move forward. Arctic experts from Canada and Denmark propose making Hans Island into a condominium, a solution that has proven to resolve other conflicts in the past. I wasn’t sure what that was, but basically it is an agreement to share the island. It sometimes works temporarily, but usually doesn’t work long term. Most nations, Canada and Denmark included don’t like the idea of giving up their sovereignty. Time will tell, I guess, but if you ask me, the whole thing is…well, it’s just comical.

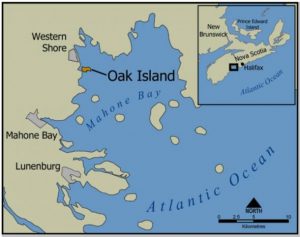

At one time or another, most of us dream of stumbling upon a buried or hidden treasure. Of course, most of those who dream about that, do so as kids, and usually after reading some story about buried treasure in a book, or watching a movie about such an event. One such buried treasure story that somehow endured for more than two centuries, is that of the Oak Island Treasure. Oak Island is located off Nova Scotia, Canada, and has been touted as the location of a money pit of buried treasure that was supposedly left there by the pirate, Captain William Kidd (1645-1701). The story seems credible enough to have led to numerous expeditions costing millions of dollars to travel to the island to search for the treasure. Unfortunately, these expeditions were to no avail, and the treasure has never been found. Perhaps it never existed, or maybe Captain Kidd or some other early treasure hunter came for it and took it away before the story even broke about its existence.

At one time or another, most of us dream of stumbling upon a buried or hidden treasure. Of course, most of those who dream about that, do so as kids, and usually after reading some story about buried treasure in a book, or watching a movie about such an event. One such buried treasure story that somehow endured for more than two centuries, is that of the Oak Island Treasure. Oak Island is located off Nova Scotia, Canada, and has been touted as the location of a money pit of buried treasure that was supposedly left there by the pirate, Captain William Kidd (1645-1701). The story seems credible enough to have led to numerous expeditions costing millions of dollars to travel to the island to search for the treasure. Unfortunately, these expeditions were to no avail, and the treasure has never been found. Perhaps it never existed, or maybe Captain Kidd or some other early treasure hunter came for it and took it away before the story even broke about its existence.

You might think that after more than 200 years, people would assume the whole thing was a hoax, give up, and move on with their lives. Well, you would be wrong. Between books and documentaries, the mystery of Oak Island’s hidden treasure is not likely to die out soon. It is even said that there must be seven deaths in search  of the treasure, before the island will yield its hold of whatever might be hidden there. To date, there have been six deaths in the searches. I don’t think that would motivate me to head out and look for it.

of the treasure, before the island will yield its hold of whatever might be hidden there. To date, there have been six deaths in the searches. I don’t think that would motivate me to head out and look for it.

Oak Island is a 140-acre privately owned island in Lunenburg County on the south shore of Nova Scotia, Canada. The tree-covered island is one of about 360 small islands in Mahone Bay and rises to a maximum of 36 feet above sea level. The island is located 660 feet from shore and connected to the mainland by a causeway and gate. The nearest community is the rural community of Western Shore which faces the island, while the nearest town is Chester.

Oak Island was, for the most part granted to the Monro, Lynch, Seacombe and Young families around the same time as the establishment of Chester on 1759. The first major group of settlers arrived in the Chester area from Massachusetts in 1761. The following year, Oak Island was officially surveyed and divided into 32 four-acre lots. Of course, if there was a treasure, it was already buried before the land was divided.

In 1965, a man named Robert Dunfield constructed a causeway from the western end of the island to Crandall’s Point on the mainland, making it more accessible to people. Oak Island Tours now owns 78% of the island, and 22% is owned by private parties. There are two permanent homes and two cottages occupied part-time on the  island. Since the 1850s, there have been documented treasure hunts, investigations, and excavations on Oak Island, but to no avail. There are many theories about what might be buried there, if anything really is. Areas of interest on the island with regard to treasure hunters include a location known as the Money Pit, a formation of boulders called Nolan’s Cross, the beach at Smith’s Cove, and a triangle-shaped swamp. The Money Pit area has been repeatedly excavated. Skeptics argue that there is no treasure and that the Money Pit is a natural phenomenon, but then they are probably look upon as wanting to keep any treasure for themselves. Until something is found, the treasure remains a mystery and a myth.

island. Since the 1850s, there have been documented treasure hunts, investigations, and excavations on Oak Island, but to no avail. There are many theories about what might be buried there, if anything really is. Areas of interest on the island with regard to treasure hunters include a location known as the Money Pit, a formation of boulders called Nolan’s Cross, the beach at Smith’s Cove, and a triangle-shaped swamp. The Money Pit area has been repeatedly excavated. Skeptics argue that there is no treasure and that the Money Pit is a natural phenomenon, but then they are probably look upon as wanting to keep any treasure for themselves. Until something is found, the treasure remains a mystery and a myth.

I recently read a book about the orphan trains, which ran between 1854 and 1929. During that time, approximately 250,000 orphaned, abandoned, and homeless children ride the train throughout the United States and Canada, to be placed with families who were looking for a child, or just as often, a worker for their farm. The orphan train movement was necessary, because at the time, it was estimated that 30,000 abandoned children were living in the streets in New York City. I had heard of the orphan trains, mostly from the movie called “Orphan Train,” but much of what really happened with those children was very new to me, and quite shocking.

I recently read a book about the orphan trains, which ran between 1854 and 1929. During that time, approximately 250,000 orphaned, abandoned, and homeless children ride the train throughout the United States and Canada, to be placed with families who were looking for a child, or just as often, a worker for their farm. The orphan train movement was necessary, because at the time, it was estimated that 30,000 abandoned children were living in the streets in New York City. I had heard of the orphan trains, mostly from the movie called “Orphan Train,” but much of what really happened with those children was very new to me, and quite shocking.

Today, while my husband, Bob Schulenberg and I were in the Black Hills, we rode the 1880 Train, as we almost always do when we are here. When they mentioned that the train had been  used in the movie “Orphan Train,” a fact that I had heard many times before, the stories from the book I had read came back to mind. My mind instantly meshed to train, the book, and the movie into one event.

used in the movie “Orphan Train,” a fact that I had heard many times before, the stories from the book I had read came back to mind. My mind instantly meshed to train, the book, and the movie into one event.

The children who traveled on the orphan trains were victims of circumstance, and they had no control over their lives at all. Each one hoped that their new family would be nice. The older ones didn’t have high hopes. The older boys pretty much knew that they would be farm hands. And most of them were right many were made to sleep in the barn, because they were thought to be thieves. If they were thieves, it was because they had to steal to survive. They did whatever it took to survive.

As Bob and I rode the train today, in the eye of my imagination, I could picture what it must have been like to be one of those orphans. The were sitting there watching that big steam engine take them to someplace they didn’t know, and probably didn’t want to go. They didn’t have high hopes for a great future, but then again, the past wasn’t that great either. They were forced to make the best of a bad situation, and the people who were in charge didn’t really care what happened to them. They were just doing their jobs. I have ridden the 1880 Train many times before, but today, it felt a little bit different, somehow. I knew that I wasn’t an orphan riding that train, but I certainly felt empathy for the children who were.

As Bob and I rode the train today, in the eye of my imagination, I could picture what it must have been like to be one of those orphans. The were sitting there watching that big steam engine take them to someplace they didn’t know, and probably didn’t want to go. They didn’t have high hopes for a great future, but then again, the past wasn’t that great either. They were forced to make the best of a bad situation, and the people who were in charge didn’t really care what happened to them. They were just doing their jobs. I have ridden the 1880 Train many times before, but today, it felt a little bit different, somehow. I knew that I wasn’t an orphan riding that train, but I certainly felt empathy for the children who were.