berlin wall

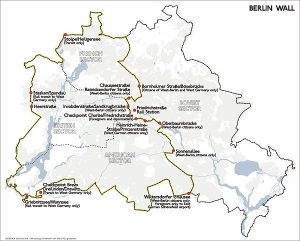

In August of 1961, virtually overnight, the Berlin appeared, separating East and West Berliners from each other. Streets, subway lines, bus lines, tramlines, canals, and rivers were divided. Family members, friends, lovers, schoolmates, work colleagues, and others were abruptly separated. For many, life was put on hold. That meant that families were instantly separated from each other, and there was nothing anyone could do about it. If a child was spending the night with a grandparent, they now had to stay there. If couples were separated, possibly due to jobs or something, they couldn’t get back together. Families who lived on opposite sides of town, couldn’t see each other. No recourse. All the families could do was stand beside the wall and talk to each other.

In August of 1961, virtually overnight, the Berlin appeared, separating East and West Berliners from each other. Streets, subway lines, bus lines, tramlines, canals, and rivers were divided. Family members, friends, lovers, schoolmates, work colleagues, and others were abruptly separated. For many, life was put on hold. That meant that families were instantly separated from each other, and there was nothing anyone could do about it. If a child was spending the night with a grandparent, they now had to stay there. If couples were separated, possibly due to jobs or something, they couldn’t get back together. Families who lived on opposite sides of town, couldn’t see each other. No recourse. All the families could do was stand beside the wall and talk to each other.

From the time of its construction, it was more than two years after before anyone was able to cross from one side of the wall to the other. In the meantime, children grew, children were born, people died. Some children and grandchildren never got to see their parents or grandparents again. The whole purpose of the Berlin Wall was to force the people in East Berlin to accept communism. The only way they “might be able” to stay alive was to comply. So, the citizens of East Berlin became virtual prisoners overnight. Their sentence was long, and they had no trial. They were simply locked up in their own city.

The “sentence” continued for more than two years, before anything changed. Then, finally, on December 20, 1963, nearly 4,000 West Berliners were allowed to cross into East Berlin to visit relatives. It was called a “one-day pass” and didn’t mean the end of the siege. Nevertheless, it was a moment of hope. The day was a result

of an agreement reached between East and West Berlin. Eventually, over 170,000 passes were issued to West Berlin citizens, each pass allowing a one-day visit to communist East Berlin. Of course, there would be no passes for East German citizens to visit the west. The government knew they would not come back.

of an agreement reached between East and West Berlin. Eventually, over 170,000 passes were issued to West Berlin citizens, each pass allowing a one-day visit to communist East Berlin. Of course, there would be no passes for East German citizens to visit the west. The government knew they would not come back.

The day was marketed as a “wonderful government” doing some kind of a great thing. There were also moments of poignancy and propaganda. The reunions who were filled with tears, laughter, and other outpourings of emotions as mothers and fathers, sons and daughters finally met again. They were grateful, if only for a short time. The tensions of the Cold War were ever close by.

As people crossed through the checkpoints, loudspeakers in East Berlin greeted them. They were told that they were now in “the capital of the German Democratic Republic,” a political division that most West Germans refused to accept. The propaganda continued as each visitor was given a brochure that explained that the wall was built to “protect our borders against the hostile attacks of the imperialists.” They were told that decadent western culture, including “Western movies” and “gangster stories,” were flooding into East Germany before the wall sealed off such dangerous trends. The picture they were painting was of the East German government being the “saviors of the morality” of the people.

The West Berliners weren’t terribly happy either and many newspapers charged that the visitors charging that they were just pawns of East German government propaganda. It was said that the whole thing was a ploy to

gain West German acceptance of a permanent division of Germany. Whatever the case may be, the visitors felt that they had no choice to comply with the rules, because their hearts were being torn out by these separations. The separation continued until President Reagan called for the wall to be torn down in a speech in West Berlin on June 12, 1987…almost 26 years after it was built.

gain West German acceptance of a permanent division of Germany. Whatever the case may be, the visitors felt that they had no choice to comply with the rules, because their hearts were being torn out by these separations. The separation continued until President Reagan called for the wall to be torn down in a speech in West Berlin on June 12, 1987…almost 26 years after it was built.

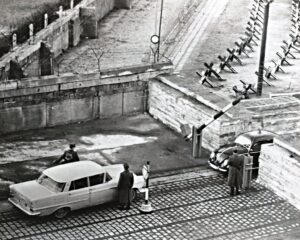

Imagine living in a country where you could only go places and do things that the government allowed you to. Communist countries are that way, but in East Berlin things had taken a much more sinister turn. Throughout the 1950s and into the early 1960s, thousands of people from East Berlin crossed over into West Berlin to reunite with families and escape communist repression. The Soviet Union had rejected East Germany’s original request to build the wall in 1953, but with defections through West Berlin reaching 1,000 people a day by the summer of 1961, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev finally relented. The residents of Berlin awoke on the morning of August 13, 1961, to find barbed wire fencing had been installed on the border between the city’s east and west sections. Days later, East Germany began to fortify the barrier with concrete. Construction began on August 12, 1961. The Berlin Wall was actually two walls. The 27 mile portion of the barrier separating Berlin into east and west consisted of two concrete walls between which was a “death strip” up to 160 yards wide that contained hundreds of watchtowers, miles of anti-vehicle trenches, guard dog runs, floodlights and trip-wire machine guns. Overnight, people who had family on the other side of Berlin were no longer able to see them. There was no recourse, and no warning. At first people could see their loved ones across the fence, but when the walls went up that ended too.

Imagine living in a country where you could only go places and do things that the government allowed you to. Communist countries are that way, but in East Berlin things had taken a much more sinister turn. Throughout the 1950s and into the early 1960s, thousands of people from East Berlin crossed over into West Berlin to reunite with families and escape communist repression. The Soviet Union had rejected East Germany’s original request to build the wall in 1953, but with defections through West Berlin reaching 1,000 people a day by the summer of 1961, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev finally relented. The residents of Berlin awoke on the morning of August 13, 1961, to find barbed wire fencing had been installed on the border between the city’s east and west sections. Days later, East Germany began to fortify the barrier with concrete. Construction began on August 12, 1961. The Berlin Wall was actually two walls. The 27 mile portion of the barrier separating Berlin into east and west consisted of two concrete walls between which was a “death strip” up to 160 yards wide that contained hundreds of watchtowers, miles of anti-vehicle trenches, guard dog runs, floodlights and trip-wire machine guns. Overnight, people who had family on the other side of Berlin were no longer able to see them. There was no recourse, and no warning. At first people could see their loved ones across the fence, but when the walls went up that ended too.

For almost 2½ years those on one side of the wall were lost to those on the other side of the wall. What the Communist regime didn’t anticipate was the fact that people would still find a way to escape. There were 39 deaths at the Berlin Wall between 1961 and 1963, and a total of 139 between 1961 and the wall’s demolition in 1989. That might not seem like so many, but when you take into account the fact that the people inside East Berlin were so closely watched, that it was almost impossible to get to supplies they needed to plan and carry out their escape attempt. Nevertheless, some people did make it safely across. No one knows for sure exactly how many people reached the western part, but some estimates claim that 5,000 East Germans reached West Berlin via the Wall. Men, women and children snuck through checkpoints, hid in vehicles and tunneled under  the concrete. They used hot air balloons, diverted the train, crossed the river on an air mattress, by swimming, and even by zip line and tight rope. These people really wanted their freedom.

the concrete. They used hot air balloons, diverted the train, crossed the river on an air mattress, by swimming, and even by zip line and tight rope. These people really wanted their freedom.

Finally, on December 20th through 26th or 1963, the Communist regime decided that if they issued 1 day passes to those in West Berlin, maybe it would stop the escape attempts. The East Berliners were not allowed to leave, but the West Berliners could come in and see friends and family members. I can only imagine how the people from West Berlin felt. They wanted to go and see their friends and family, but would they be allowed back out, or was this just a trap? Nevertheless, it was Christmastime, and it had been so long since they had seen them. So, nearly 4,000 West Berliners crossed into East Berlin to visit their relatives. It was all part of an agreement reached between East and West Berlin, over 170,000 passes were eventually issued to West Berlin citizens, each pass allowing a one day visit to communist East Berlin for the Christmas (Passierscheinregelung) season that year.

The day was one filled with moments of poignancy and propaganda. Tears, laughter, and other outpourings of emotions characterized the reunions that took place as mothers and fathers, sons and daughters met again. They were so happy, if only for a short time. Cold War tensions were mixed in too, however. Loudspeakers in East Berlin inundated visitors with the news that they were now in “the capital of the German Democratic Republic,” a political division that most West Germans refused to accept. Visitors were also given a brochure that explained that the wall was built to “protect our borders against the hostile attacks of the imperialists.” They were told of how the decadent western culture, including “Western movies” and “gangster stories,” were flooding into East Germany before the wall sealed off such dangerous trends, and that made it “necessary” to build the wall. West Berlin newspapers berated the visitors for being “pawns” of East German propaganda. Editorials argued that the communists would use these visits to gain West German acceptance of a permanent division of Germany. The visits, and the high-powered rhetoric that surrounded them, reminded everyone that the Cold  War involved very human, often quite heated, emotions. East Berlin allowed these similar and very limited arrangements in 1964, 1965 and 1966. In 1971, with the Four Power Agreement on Berlin, agreements were finally reached to allow West Berliners to apply for visas to enter East Berlin and East Germany regularly, however, East German authorities could still refuse to honor the entry permits. Finally in 1989, at President Ronald Reagan’s insistence, the Berlin Wall came down, and this inhumane treatment of the East German people ended.

War involved very human, often quite heated, emotions. East Berlin allowed these similar and very limited arrangements in 1964, 1965 and 1966. In 1971, with the Four Power Agreement on Berlin, agreements were finally reached to allow West Berliners to apply for visas to enter East Berlin and East Germany regularly, however, East German authorities could still refuse to honor the entry permits. Finally in 1989, at President Ronald Reagan’s insistence, the Berlin Wall came down, and this inhumane treatment of the East German people ended.

I’ve been spending some very enjoyable time emailing with my cousin, Dennis Fredrick lately, and the subject of Great Aunt Bertha Schumacher Hallgren’s journal came up again. That is all it takes for me to decide that I need to read it again. I can’t get over the draw that journal has on me. Every time I read it again, something more jumps out at me. Another little tidbit of her amazing personality, because you see, my Great Aunt Bertha was an amazing person. She had the ability to see things around her in a deeper and sometimes, different way than others. Her curious mind wondered about the events taking place, and their impact on the future. And she had a foresight that many people just don’t have. I love her vision.

I’ve been spending some very enjoyable time emailing with my cousin, Dennis Fredrick lately, and the subject of Great Aunt Bertha Schumacher Hallgren’s journal came up again. That is all it takes for me to decide that I need to read it again. I can’t get over the draw that journal has on me. Every time I read it again, something more jumps out at me. Another little tidbit of her amazing personality, because you see, my Great Aunt Bertha was an amazing person. She had the ability to see things around her in a deeper and sometimes, different way than others. Her curious mind wondered about the events taking place, and their impact on the future. And she had a foresight that many people just don’t have. I love her vision.

I didn’t get very far…the first page, in fact…before something new jumped out. She was talking about the dislike many people have of history, and how few want to write about it, except when it comes to family history. I think that is probably because they feel somehow connected to the events of the past, when they think about the fact that their ancestors lived those events. She talked about the idea of people writing about family histories taking off, and becoming a vast project that connected many people. She mentioned that, if writing about family history ever became popular to a wide scale, future generations could read about them centuries from now. Sometimes, I wonder what she would think of her idea of family history studies on a wide scale, because that is exactly what we have these days. Maybe, she could see a bit into the future, and in her mind envision events that were going to come about, much like Jules Verne did with some of his writings.

She encourages people to add to with family history, the human side, because without it, the history becomes dry reading of statistics with no heart to it. Great Aunt Bertha felt that we were living in amazing times at the time of her journal, and while many people would think she meant the 1800s, she did not. She was talking about 1980. I lived through the 1980s, and I can’t say that I ever felt like they were anything so special, but  looking back now, I think about the man that many of us consider to be the greatest president we have ever had, Ronald Reagan. Those were days of recovery from the tense days of the 1970s and the big government we had then. They were days when taxes were cut, and government was limited, and things began to get better. The Cold War was winding down, and we saw the Berlin Wall come down at Reagan’s insistence. Thinking back I can see that Great Aunt Bertha was right. The 1980s were amazing days, but then so are many other times in our nation’s history. We just have to look at those days and realize that each generation has its greatness. That was the kind of thing my great aunt saw, but as I said, she saw deeper into a situation than most people saw, and she also saw the value of the insight she found by looking deeper.

looking back now, I think about the man that many of us consider to be the greatest president we have ever had, Ronald Reagan. Those were days of recovery from the tense days of the 1970s and the big government we had then. They were days when taxes were cut, and government was limited, and things began to get better. The Cold War was winding down, and we saw the Berlin Wall come down at Reagan’s insistence. Thinking back I can see that Great Aunt Bertha was right. The 1980s were amazing days, but then so are many other times in our nation’s history. We just have to look at those days and realize that each generation has its greatness. That was the kind of thing my great aunt saw, but as I said, she saw deeper into a situation than most people saw, and she also saw the value of the insight she found by looking deeper.