american

It has been 74 years since 17,740 Americans gave their lives to liberate the people of the Netherlands (often called Holland) from the Germans during World War II, and the people of Holland have never forgotten that sacrifice. For 74 years now, the people of the small village of Margraten, Netherlands have taken care of the graves of the lost at the Margraten American Cemetery. On Memorial Day, they come, every year, bringing Memorial Day bouquets for men and women they never knew, but whose 8,300 headstones the people of the Netherlands have adopted as their own. Of the 17,740 who were originally buried there, 9,440 were later moved to various paces in he United States by their families. “What would cause a nation recovering from losses and trauma of their own to adopt the sons and daughters of another nation?” asked Chotin, the only American descendant to speak on that Sunday 4 years ago. “And what would keep that commitment alive for all of these years, when the memory of that war has begun to fade? It is a unique occurrence in the history of civilization.”

It has been 74 years since 17,740 Americans gave their lives to liberate the people of the Netherlands (often called Holland) from the Germans during World War II, and the people of Holland have never forgotten that sacrifice. For 74 years now, the people of the small village of Margraten, Netherlands have taken care of the graves of the lost at the Margraten American Cemetery. On Memorial Day, they come, every year, bringing Memorial Day bouquets for men and women they never knew, but whose 8,300 headstones the people of the Netherlands have adopted as their own. Of the 17,740 who were originally buried there, 9,440 were later moved to various paces in he United States by their families. “What would cause a nation recovering from losses and trauma of their own to adopt the sons and daughters of another nation?” asked Chotin, the only American descendant to speak on that Sunday 4 years ago. “And what would keep that commitment alive for all of these years, when the memory of that war has begun to fade? It is a unique occurrence in the history of civilization.”

The people of Margraten immediately embraced the Americans, who had come to their aid when they needed it most. The town’s mayor invited the company’s commanders to sleep in his home, while the enlisted men slept in the schools. The protection against rain and buzz bombs was welcomed. Later, villagers hosted U.S. troops when the men were given rest-and-recuperation breaks from trying to breach the German frontier defenses, known as the Siegfried Line. “After four dark years of occupation, suddenly [the Dutch] people were free from the Nazis, and they could go back to their normal lives and enjoy all the freedoms they were used to. They knew they had to thank the American allies for that,” explained Frenk Lahaye, an associate at the cemetery.

By November 1944, two months after the village’s 1,500 residents had been freed from Nazi occupation by the U.S. 30th Infantry Division the town’s people were filled with gratitude, but the war wasn’t over. In late 1944  and early 1945, thousands of American soldiers would be killed in nearby battles trying to pierce the German defense lines. The area was filled with Booby-traps and heavy artillery fire. All that combined with a ferocious winter, dealt major setbacks to the Allies, who had already suffered losses trying to capture strategic Dutch bridges crossing into Germany during the ill-fated Operation Market Garden.

and early 1945, thousands of American soldiers would be killed in nearby battles trying to pierce the German defense lines. The area was filled with Booby-traps and heavy artillery fire. All that combined with a ferocious winter, dealt major setbacks to the Allies, who had already suffered losses trying to capture strategic Dutch bridges crossing into Germany during the ill-fated Operation Market Garden.

Now, the U.S. military needed a place to bury its fallen. The Americans ultimately picked a fruit orchard just outside Margraten. On the first day of digging, the sight of so many bodies made the men in the 611th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company ill. The bodies arrived in a procession of trucks and trailers. Death hung in the air over the whole village of Margraten. The sight of so much death caused a few of the people helping with the burials to become ill. They suddenly made a break for the latrines. The first burial at Margraten took place on November 10, 1944. Laid to rest in Plot A, Row 1, Grave 1: John David Singer Jr, a 25-year-old infantryman, whose remains would later be repatriated and buried in Denton, Maryland, about 72 miles east of Washington. Between late 1944 and spring 1945, up to 500 bodies arrived each day, so many that the mayor went door to door asking villagers for help with the digging. Over the next two years, about 17,740 American soldiers would be buried here, though the number of graves would shrink as thousands of families asked for their loved ones’ remains to be sent home, until 8,300 remained, and still, the graves are cared for by the town’s people, as if the dead were their own loved one. Not only that, but they have taken it upon themselves to research the deceased, and learn of their lives as a way of showing honor to these fallen heroes.

On May 29, 1945, the day before the cemetery’s first Memorial Day commemoration, 20 trucks from the 611th  collected flowers from 60 different Dutch villages. Nearly 200 Dutch men, women and children spent all night arranging flowers and wreaths by the dirt-covered graves, which bore makeshift wooden crosses and Stars of David. By 8am, the road leading into Margraten was jammed with Dutch people coming on foot, bicycle, carriages, horseback and by car. Silent film footage shot that day shows some of the men wearing top hats as they carried wreaths. A nun and two young girls laid flowers at a grave, then prayed. Solemn-faced children watched as cannons blasted salutes. The Dutch, Shomon wrote, “were perceptibly stirred, wept in bowed reverence.” All they do for these heroes is because they have vowed never to forget.

collected flowers from 60 different Dutch villages. Nearly 200 Dutch men, women and children spent all night arranging flowers and wreaths by the dirt-covered graves, which bore makeshift wooden crosses and Stars of David. By 8am, the road leading into Margraten was jammed with Dutch people coming on foot, bicycle, carriages, horseback and by car. Silent film footage shot that day shows some of the men wearing top hats as they carried wreaths. A nun and two young girls laid flowers at a grave, then prayed. Solemn-faced children watched as cannons blasted salutes. The Dutch, Shomon wrote, “were perceptibly stirred, wept in bowed reverence.” All they do for these heroes is because they have vowed never to forget.

Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess were senior officials in the British Foreign Office and in 1951. They were trusted diplomats, but they had a dark side. They were well known to have left-leaning ideas, and eventually their ideas moved them so far out of line with the jobs they had that it was suspected, if not known that they had become spies for the Soviet Union. Maclean and Burgess were two of the original members of the notorious Cambridge Spy Ring, which was a ring of spies in the United Kingdom, who passed information to the Soviet Union during World War II. They were active at least into the early 1950s. Four members of the ring were originally identified: Kim Philby (cryptonym: Stanley), Donald Duart Maclean (cryptonym: Homer), Guy Burgess (cryptonym: Hicks) and Anthony Blunt (cryptonyms: Tony, Johnson). Once jointly known as the Cambridge Four and later as the Cambridge Five, the number increased as more evidence came to light.

Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess were senior officials in the British Foreign Office and in 1951. They were trusted diplomats, but they had a dark side. They were well known to have left-leaning ideas, and eventually their ideas moved them so far out of line with the jobs they had that it was suspected, if not known that they had become spies for the Soviet Union. Maclean and Burgess were two of the original members of the notorious Cambridge Spy Ring, which was a ring of spies in the United Kingdom, who passed information to the Soviet Union during World War II. They were active at least into the early 1950s. Four members of the ring were originally identified: Kim Philby (cryptonym: Stanley), Donald Duart Maclean (cryptonym: Homer), Guy Burgess (cryptonym: Hicks) and Anthony Blunt (cryptonyms: Tony, Johnson). Once jointly known as the Cambridge Four and later as the Cambridge Five, the number increased as more evidence came to light.

The group was recruited during their education at the University of Cambridge in the 1930s…hence the term Cambridge. There is much debate as to the exact timing of their recruitment by Soviet intelligence. Anthony Blunt claimed that they were not recruited as agents until they had graduated. Blunt, an Honorary Fellow of Trinity College, was several years older than Burgess, Maclean, and Philby; he acted as a talent-spotter and recruiter for most of the group save Burgess. Several people have been suspected of being additional members of the group; John Cairncross (cryptonym: Liszt) was identified as such by Oleg Gordievsky, although many others have also been accused of membership in the Cambridge ring. Both Blunt and Burgess were members of the Cambridge Apostles, an exclusive and prestigious society based at Trinity and King’s Colleges. Cairncross was also an Apostle. Other Apostles accused of having spied for the Soviets include Michael Whitney Straight and Guy Liddell.

The group was radical in their dealings, so I’m not sure that anyone was overly surprised when both Maclean and Burgess disappeared from England in 1951, although they may have assumed that they were assassinated. For years there was no trace of them, and I suppose people began to forget all about them. Nevertheless, there were rumors that they had been spies for the Soviet Union and had left England to avoid prosecution. For five years, nothing was heard of the pair. British intelligence suspected that they were in the Soviet Union, but Russian officials consistently denied any knowledge of their whereabouts.

Then, on February 11, 1956, the pair resurfaced and invited a group of journalists to a hotel room in Moscow. Burgess and Maclean were there to greet them, give a brief interview, and hand out a typed joint statement. In the statement, both men denied having served as Soviet spies. However, they very strongly declared their sympathy with the Soviet Union and stated that they had both been “increasingly alarmed by the post-war character of Anglo-American policy.” They claimed that the decision to leave England and live in Russia was due to their belief that only in Russia would there be “some chance of putting into practice in some form the convictions they had always had.” They were convinced that the Soviet Union desired a policy of “mutual understanding” with the West, but many officials in the United States and Great Britain were adamant in  their opposition to any working relationship with the Russians. They concluded by stating, “Our life in the Soviet Union convinced us we took at the time the correct decision.”

their opposition to any working relationship with the Russians. They concluded by stating, “Our life in the Soviet Union convinced us we took at the time the correct decision.”

While the surprise news conference solved the mystery of where Burgess and Maclean had been for the past five years, it did little to settle the question of why they had gone to the Soviet Union in the first place. Their statement also did not clear up the issue of whether or not they had spied for the Soviet Union. Evidence from both British and American intelligence agencies strongly suggested that the two, together with fellow Foreign Office workers Kim Philby and Sir Anthony Blunt, had engaged in espionage for the Russians. Both men spent the rest of their lives in the Soviet Union. Burgess died in 1963 and Maclean passed away in 1983. I don’t suppose we will ever know all of the British and possibly American secrets they shared with the Russians during those years, only that they were treasonous traitors.

Most people think that English came from England, and of course, it did, however, in England prior to the 19th century, the English language was not spoken by the aristocracy, but rather only by “commoners.” Back then, English used to belong to the people, and I suppose that might explain some of the “incorrect” uses of the language which have been so severely attacked by contemporary English speakers. Prior to the 19th century, the aristocracy in English courts spoke French. This was due to the Norman Invasion of 1066 and caused years of division between the “gentlemen” who had adopted the Anglo-Norman French and those who only spoke English. Even the famed King Richard the Lionheart was actually primarily referred to in French, as Richard “Coeur de Lion.”

Most people think that English came from England, and of course, it did, however, in England prior to the 19th century, the English language was not spoken by the aristocracy, but rather only by “commoners.” Back then, English used to belong to the people, and I suppose that might explain some of the “incorrect” uses of the language which have been so severely attacked by contemporary English speakers. Prior to the 19th century, the aristocracy in English courts spoke French. This was due to the Norman Invasion of 1066 and caused years of division between the “gentlemen” who had adopted the Anglo-Norman French and those who only spoke English. Even the famed King Richard the Lionheart was actually primarily referred to in French, as Richard “Coeur de Lion.”

In my opinion, this dual language society would have caused numerous problems. The indication I get is that neither side could speak the language of the other, but I don’t know how a monarchy could rule, if the “commoners” could not understand the language and therefore the orders of the monarchy. French was spoken and learned by anyone in the upper  classes. However, it became less useful as English lost its control of various places in France, where the peasants spoke French, too. After that…about, 1450…English was simply more useful for talking to anybody. It is still true that British royals and many nobles are fluent in French, but they only use it to talk to French people, just like everybody else.

classes. However, it became less useful as English lost its control of various places in France, where the peasants spoke French, too. After that…about, 1450…English was simply more useful for talking to anybody. It is still true that British royals and many nobles are fluent in French, but they only use it to talk to French people, just like everybody else.

To further confuse your preconceptions about the English language, the “British accent” was, in reality, created after the Revolutionary War, meaning contemporary Americans sound more like the colonists and British soldiers of the 18th century than contemporary Brits. Many people have made a point of how much they love the British accent, but I think very few people know the real story behind the British accent. In the 18th century and before, the British “accent” was the way we speak herein America. Of course, accents vary greatly  by region, as we have seen with the accents of the south and east in the United States, but the “BBC English” or public school English accent…which sounds like the James Bond movies…didn’t come about until the 19th century and was originally adopted by people who wanted to sound fancier. I suppose it was like the aristocracy and the commoners, in that one group didn’t want to be mistaken for the other. After being handily defeated by the American colonists, I’m sure that the British were looking for a way to seem superior, even in defeat. The change in the accent of the English language was sufficient to make that distinction. Maybe it was their way of saying that they were better than the American guerilla-type soldiers who beat them in combat…basically they might have lost, but they were superior…even if it was only in how they sounded.

by region, as we have seen with the accents of the south and east in the United States, but the “BBC English” or public school English accent…which sounds like the James Bond movies…didn’t come about until the 19th century and was originally adopted by people who wanted to sound fancier. I suppose it was like the aristocracy and the commoners, in that one group didn’t want to be mistaken for the other. After being handily defeated by the American colonists, I’m sure that the British were looking for a way to seem superior, even in defeat. The change in the accent of the English language was sufficient to make that distinction. Maybe it was their way of saying that they were better than the American guerilla-type soldiers who beat them in combat…basically they might have lost, but they were superior…even if it was only in how they sounded.

My niece, Siara Harman is one of many girls who were cheerleaders in high school and college. She even won a State Championship and a Grand National Championship with the Kelly Walsh Cheer Squad in 2011. Since it’s beginnings, cheerleading has come a long way. In fact, I doubt if today’s cheerleaders would recognize their earlier counterparts, if they saw them back then. Siara was a skilled cheerleader, and very athletic, and we are all proud of her cheerleading years.

My niece, Siara Harman is one of many girls who were cheerleaders in high school and college. She even won a State Championship and a Grand National Championship with the Kelly Walsh Cheer Squad in 2011. Since it’s beginnings, cheerleading has come a long way. In fact, I doubt if today’s cheerleaders would recognize their earlier counterparts, if they saw them back then. Siara was a skilled cheerleader, and very athletic, and we are all proud of her cheerleading years.

The roots of American cheerleading are closely tied to American football’s roots. The first intercollegiate football game was played on November 6, 1869, between Princeton University and Rutgers University in New Jersey. By the 1880s, Princeton had formed an pep club. Organized cheering started as an all-male activity, as many sports do. As early as 1877, Princeton University had a Princeton Cheer. Basically, it was a fight song that was documented in the February 22, 1877; March 12, 1880; and November 4, 1881, issues of The Daily Princetonian. This cheer was yelled from the stands by students attending games, as well as by the athletes themselves. The cheer, “Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah! Tiger! S-s-s-t! Boom! A-h-h-h!” remains in use with slight modifications today, where it is now referred to as the Locomotive. Princeton class of 1882 graduate Thomas Peebles moved to Minnesota in 1884. He took with him the idea of organized crowds cheering at football games to the University of Minnesota. The term “Cheer Leader” had been used as early as 1897, with Princeton’s football officials having named three students as Cheer Leaders: Thomas, Easton, and Guerin from Princeton’s classes of 1897, 1898, and 1899, respectively, on October 26, 1897. These students would cheer for the team also at football practices, and special cheering sections were designated in the stands for the games themselves for both the home and visiting teams. On November 2, 1898, the University of Minnesota was on a losing streak. A medical student named Johnny Campbell assembled a group to energize the team and the crowd. Johnny picked up a megaphone and rallied the team to victory with the first organized cheer: “Rah, Rah, Rah! Ski-U-Mah! Hoo-Rah! Hoo-Rah! Varsity! Varsity! Minn-e-so-tah!” With that action, Campbell became the first cheerleader in America. Soon after, the University of Minnesota organized a “yell leader” squad of six male students, who still use Campbell’s original cheer today. In 1903, the first cheerleading fraternity, Gamma Sigma, was founded.

In 1923, at the University of Minnesota, women were finally permitted to participate in cheerleading. However, it took time for other schools to follow. In the late 1920s, many school manuals and newspapers that were published still referred to cheerleaders as chap, fellow, and man. Women cheerleaders were overlooked until the 1940s, when collegiate men were drafted for World War II, creating the opportunity for more women to make their way onto sporting event sidelines. As noted by Kieran Scott in Ultimate Cheerleading: “Girls really took over for the first time.” A report written on behalf of cheerleading in 1955 explained that in larger schools, “occasionally boys, as well as, girls are included,” and in smaller schools, “boys can usually find their place in the athletic program, and cheerleading is likely to remain solely a feminine occupation.” During the 1950s, cheerleading in America also increased in popularity. By the 1960s, some began to consider cheerleading too feminine an extracurricular activity for boys, and by the 1970s, girls primarily cheered at public school games. However, this did not stop its growth. Cheerleading could be found at almost every school level across

the country, even youth leagues. In 1975, it was estimated by a man named Randy Neil that over 500,000 students actively participated in American cheerleading from grade school to the collegiate level. He also approximated that 95% of cheerleaders within America were female. Since 1973, cheerleaders have started to attend female basketball and other all-female sports as well. As of 2005, overall statistics show around 97% of all modern cheerleading participants are female, although at the collegiate level, cheerleading is co-ed with about 50% of participants being male.

the country, even youth leagues. In 1975, it was estimated by a man named Randy Neil that over 500,000 students actively participated in American cheerleading from grade school to the collegiate level. He also approximated that 95% of cheerleaders within America were female. Since 1973, cheerleaders have started to attend female basketball and other all-female sports as well. As of 2005, overall statistics show around 97% of all modern cheerleading participants are female, although at the collegiate level, cheerleading is co-ed with about 50% of participants being male.

In the United States, you don’t often expect to become friends with a Russian man, but that is exactly what happened with my dad, Allen Spencer. Dad was working at WOTCO in Casper at the time, and his friend, Vladimir worked there as well. For Vladimir, the United States was the epitome of the word freedom. He loved the United States, and as an immigrant, who loved the United States, he wanted to learn the language. He was working very hard on it when he and my dad met. Dad was excited about Vladimir too. He had never known anyone from Russia, and really, never expected to. He told Mom and my younger sister, Allyn Hadlock that there was a Russian man working with him and he wanted to learn Russian so he could talk to him.

In the United States, you don’t often expect to become friends with a Russian man, but that is exactly what happened with my dad, Allen Spencer. Dad was working at WOTCO in Casper at the time, and his friend, Vladimir worked there as well. For Vladimir, the United States was the epitome of the word freedom. He loved the United States, and as an immigrant, who loved the United States, he wanted to learn the language. He was working very hard on it when he and my dad met. Dad was excited about Vladimir too. He had never known anyone from Russia, and really, never expected to. He told Mom and my younger sister, Allyn Hadlock that there was a Russian man working with him and he wanted to learn Russian so he could talk to him.

Dad bought a Russian/English dictionary, and began to study it. He had some specific phrases he wanted to learn, such as, Hello, How are you, Do you like America, and Do you have a family. Every night they sat down at the table to work through the dictionary, figuring out what he would say next. They also learned that certain symbols,  some that we use today, could mean something very different in Russian. The American symbol for “ok” is a good example. In Russian that symbol, with the circle of the thumb and forefinger, is a cuss word. It is very similar to flipping someone the bird. They laughed about that one. Then, when Dad wanted to say Dirty Rat, Allyn told him to use that American symbol for ok, because that should do it. That really got them laughing, and it still makes Allyn laugh to this day when she thinks about it.

some that we use today, could mean something very different in Russian. The American symbol for “ok” is a good example. In Russian that symbol, with the circle of the thumb and forefinger, is a cuss word. It is very similar to flipping someone the bird. They laughed about that one. Then, when Dad wanted to say Dirty Rat, Allyn told him to use that American symbol for ok, because that should do it. That really got them laughing, and it still makes Allyn laugh to this day when she thinks about it.

I think the thing that Vladimir liked so much about my dad was the fact that he tried to learn Russian, and that he reached out to a foreigner too. Vladimir and his wife didn’t have very many people that he could visit with…at least not in Russian. He was just so pleased that Dad was actually learning Russian. I’m not saying that Dad was fluent at Russian. In fact, his Russian could be considered comical at times, but the main thing was that he tried. Dad and Vladimir became the best of friends, and mom and Vladimir’s wife were friends too. They were invited to dinner at Vladimir’s house, and his wife made Borscht. Borscht is a beet soup. Now, I have to tell you that Dad must have really felt a friendship with Vladimir, because Dad hated beets, but he ate that soup. They told Mom and Dad that in Russia the people didn’t have very much meat, so their meals consisted of potatoes and vegetables. They were able to buy more meat now  though, since coming to America, so when they had their American friends over for dinner, they bought meat for the Borscht…mostly because Americans are used to eating meat.

though, since coming to America, so when they had their American friends over for dinner, they bought meat for the Borscht…mostly because Americans are used to eating meat.

Vladimir and his wife wanted to be like the American people, because they loved this country. The did their very best to Americanize everything they did, because they wanted to be true Americans. This was the true melting pot…every foreigners dream, and they wanted to be a part of it. Dad and his Russian co-worker became good friends, and Vladimir always appreciated Dad’s efforts to make him feel at home in a new land.

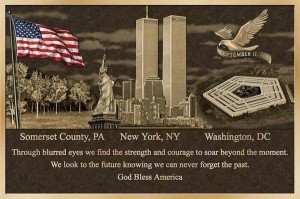

Twelve years ago today, our world was changed forever. In my remembrance and that of all living Americans, there has never been never been such an attack…here, on American soil…until September 11, 2001. That day will live in the memories of all the American people who were old enough to remember it, and any who have been told very much about it since. I have to wonder about the people born since that time. Will they understand what that day is all about? Or will they simply see it in the way most of us see things like the Civil War or the American Revolutionary War? Both were events that took place here in America so very long ago, fought on American soil, and yet, they seem more like a storybook event than a real event that is such a big part of our history. I don’t know how that could have been

Twelve years ago today, our world was changed forever. In my remembrance and that of all living Americans, there has never been never been such an attack…here, on American soil…until September 11, 2001. That day will live in the memories of all the American people who were old enough to remember it, and any who have been told very much about it since. I have to wonder about the people born since that time. Will they understand what that day is all about? Or will they simply see it in the way most of us see things like the Civil War or the American Revolutionary War? Both were events that took place here in America so very long ago, fought on American soil, and yet, they seem more like a storybook event than a real event that is such a big part of our history. I don’t know how that could have been  changed in the years following those wars, but with our technology, we should be able to keep the memory of the terrorist attacks in the front of our children’s thoughts, so that as they grow, we don’t lose sight of what the evil in this world can bring about.

changed in the years following those wars, but with our technology, we should be able to keep the memory of the terrorist attacks in the front of our children’s thoughts, so that as they grow, we don’t lose sight of what the evil in this world can bring about.

I did not know anyone who lost their life on 9-11, but I did know someone who could have been in the middle of that whole thing. My daughter’s friend, Carina, who has been like a third daughter to me since they were in Kindergarten, was a flight attendant during that time with Continental Airlines, based out of New Jersey. She was sick that day, and so was not flying. That did not alleviate her parents’ concerns, because they didn’t know that she was not flying and they  couldn’t get a hold of her, because she had turned her phone off. When we knew that she was safe, we all gave a sigh of relief. It is a feeling of relief that we will never forget.

couldn’t get a hold of her, because she had turned her phone off. When we knew that she was safe, we all gave a sigh of relief. It is a feeling of relief that we will never forget.

Now twelve years later we are again remembering a horrible terrorist attack against our nation, this time in Benghazi. Our government became too complacent about our safety both here and abroad, and again…people died…on a day when we should have been watchful!!! It is an atrocity!! When will we learn that we cannot forget. There is so much evil in this world and we must remain watchful, or we will be attacked again. Today, I pay tribute to those lost in all of these attacks, and to those who gave their lives trying to help others. Rest in peace.

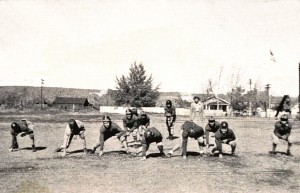

As we start football season, I recalled a picture that I had seen among my mom’s old family pictures. It was a football practice session most likely at a local school. That reminded me of something I had read a while back about the changes in football gear over the years. As we all know, football can be a dangerous game. Sometimes, the players are hurt slightly and sometimes, quite badly. Unfortunately, it was those injuries that have founded the need for better protection, and therefore, better gear. When American football appeared on college campuses in the 1870’s little was known about the brain damage that could occur from some of the impacts that are a natural part of the game.

As we start football season, I recalled a picture that I had seen among my mom’s old family pictures. It was a football practice session most likely at a local school. That reminded me of something I had read a while back about the changes in football gear over the years. As we all know, football can be a dangerous game. Sometimes, the players are hurt slightly and sometimes, quite badly. Unfortunately, it was those injuries that have founded the need for better protection, and therefore, better gear. When American football appeared on college campuses in the 1870’s little was known about the brain damage that could occur from some of the impacts that are a natural part of the game.

In those early years, head protection was rarely worn. As far back as the 1900’s, they had the “head harness” which was a soft leather version of today’s helmet, but it was mainly to protect the ears. I suppose it did, but it also made it difficult to hear, so not many players wore them. Newer versions of the helmet appeared as the years went by, featuring holes for the ears, so they could hear the plays and movement around them. They were made out of plastic, and featured a suspension system to keep the helmet from sitting directly on the player’s head. This also provided a little bit of cushion for their head. Of course, we now know that those older versions did not provide enough protection from concussion,  and the newer versions probably don’t do enough either, but they are much better than their predecessors.

and the newer versions probably don’t do enough either, but they are much better than their predecessors.

In the early years, players were subjected to ridicule for putting padding in all the necessary areas that we now know need protection. It was treated as…well, wimpy back then. Now plastic is a part of shoulder pads and pants. It isn’t a perfect solution, but the key here is to keep the players in the game, if possible, because we all know that one of the best things about fall is football…to some people anyway.