History

Friday, the 13th is not considered to be a lucky day…if you happen to be superstitious, but for almost 2500 Jewish people, as well as for Major Clarence L. Benjamin, Friday the 13th of April, 1945 would prove that Friday the 13th could be a very blessed day. While on a routine patrol a few miles northwest of Magdeburg, Benjamin and his unit came upon a railroad siding in a wooded ravine not far from the Elbe River. There, about 200 shabby looking civilians were sitting by the side of the road. Even in their shabby state, there was something immediately apparent about each one of these people, men and women, which drew immediate attention. These people were skeleton thin with starvation Their faces showed a sickness, and the way in which they stood…was like they were beaten and dejected, but there was something else. When they saw the Americans they began laughing in joy…if it could be called laughing. It was an outpouring of pure, near-hysterical relief. The reason, the unit soon found out was the railroad siding.

Friday, the 13th is not considered to be a lucky day…if you happen to be superstitious, but for almost 2500 Jewish people, as well as for Major Clarence L. Benjamin, Friday the 13th of April, 1945 would prove that Friday the 13th could be a very blessed day. While on a routine patrol a few miles northwest of Magdeburg, Benjamin and his unit came upon a railroad siding in a wooded ravine not far from the Elbe River. There, about 200 shabby looking civilians were sitting by the side of the road. Even in their shabby state, there was something immediately apparent about each one of these people, men and women, which drew immediate attention. These people were skeleton thin with starvation Their faces showed a sickness, and the way in which they stood…was like they were beaten and dejected, but there was something else. When they saw the Americans they began laughing in joy…if it could be called laughing. It was an outpouring of pure, near-hysterical relief. The reason, the unit soon found out was the railroad siding.

Standing silently on the tracks of the siding was a long string of grimy, ancient boxcars. On the banks by the tracks, trying to get some pitiful comfort from the thin April sun, sat a multitude of people of varying stages of misery. They sat motionless in despair. When they group sighted the Americans, a great stir went through this strange camp. Those who were able rushed toward the Major’s jeep and the two light tanks. On the hill to the left people were resting…some forever. About sixteen people died of starvation before food could be brought to the train. They simply couldn’t hold out any longer.

As the Major soothed the people, he eventually found some who spoke English, and their story came out. This had been, and still was, a horror train. This train which contained about 2,500 Jews, had a few days previously left the Bergen-Belsen death camp. Men, women and children, were all loaded into a few available railway cars, some passenger and some freight, but mostly the typical antiquated freight cars, called “40 and 8” cars. The term, from World War I, “40 and 8” meant that these cars would accommodate 40 men or 8 horses, but the cars were crammed with about 60 to 70 people, with standing room only for most of them. The cars were hot and it was hard to breathe. In all, the cars held about 2,500 Jews, far more than they should have.

The war was winding down, and the Nazis were trying to evacuate the concentration camps ahead of the Allied troops arrival. On April 10, 1945, three trains were sent from Bergen-Belsen with the purpose to move eastward from the Camp, to the Elbe River. They were told to reverse direction because of the rapidly advancing Russian Army. The train reversed direction and headed to Farsleben. There, they were then told that  they were heading into the advancing American Army. The train halted at Farsleben…awaiting further orders. The engineers received their orders…drive the train to, and onto the bridge over the Elbe River, and either blow it up, or just drive it off the end of the damaged bridge, with all of the cars of the train crashing into the river, and killing or drowning all of the occupants. While the engineers thought about this action, knowing that they too would be hurtling themselves to death, the Americans caught up to them. The arrival of the 743rd Tank Battalion was the only reason anyone came out of the trains alive. It was Friday the 13th…a very blessed day for these Jews. Not an ounce of bad luck there.

they were heading into the advancing American Army. The train halted at Farsleben…awaiting further orders. The engineers received their orders…drive the train to, and onto the bridge over the Elbe River, and either blow it up, or just drive it off the end of the damaged bridge, with all of the cars of the train crashing into the river, and killing or drowning all of the occupants. While the engineers thought about this action, knowing that they too would be hurtling themselves to death, the Americans caught up to them. The arrival of the 743rd Tank Battalion was the only reason anyone came out of the trains alive. It was Friday the 13th…a very blessed day for these Jews. Not an ounce of bad luck there.

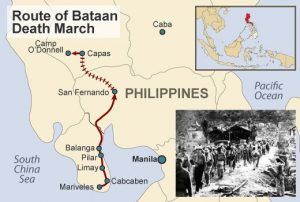

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese quickly began expanding their areas of control. They focused on the Philippine Islands, a United States territory, where tens of thousands of American and Filipino soldiers were stationed. The day after Japan bombed the US naval base at Pearl Harbor, on December 7, 1941, the Japanese invasion of the Philippines began. Without the necessary help from the US Navy, the troops stationed there quickly ran out of food and ammunition. On April 9, 1942, the soldiers had no choice but to surrender the Bataan Peninsula on the main Philippine island of Luzon to the Japanese. It was the largest army under US command ever to surrender.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese quickly began expanding their areas of control. They focused on the Philippine Islands, a United States territory, where tens of thousands of American and Filipino soldiers were stationed. The day after Japan bombed the US naval base at Pearl Harbor, on December 7, 1941, the Japanese invasion of the Philippines began. Without the necessary help from the US Navy, the troops stationed there quickly ran out of food and ammunition. On April 9, 1942, the soldiers had no choice but to surrender the Bataan Peninsula on the main Philippine island of Luzon to the Japanese. It was the largest army under US command ever to surrender.

The Japanese didn’t want these prisoners of war to be visible, so a plan was devised to move them inland. The area didn’t have railways, and because they did not expect such a large group of surrendered soldiers, it was decided that they would walk the 65 miles. So, on April 9, 1942, 75,000 Filipino and American troops on Bataan were forced to make the torturous 65 mile march to Camp O’Donnell where they were to be housed. Japan was  completely unprepared for the sheer number of soldiers who surrendered that day. The Japanese troops were filled with frustration, coupled with disdain for surrendering troops, which led to shocking brutality during the march.

completely unprepared for the sheer number of soldiers who surrendered that day. The Japanese troops were filled with frustration, coupled with disdain for surrendering troops, which led to shocking brutality during the march.

The marchers made the trek in intense heat that further complicated their situation, along with the harsh treatment by the Japanese guards. Thousands of men died along the way, in what became known as the Bataan Death March. The march began at Mariveles, on the southern end of the Bataan Peninsula. It continued 65 miles to San Fernando. The men were divided into groups of approximately 100, and the march typically took each group around five days to complete. While no one knows for sure, it is believed that thousands of troops died because of the brutality of their captors, who starved and beat the marchers, giving them no food or water, and bayoneted those too weak to walk. Those who survived were taken by rail from San Fernando to prisoner-of-war camps, where thousands died from disease, mistreatment, and starvation.

America was pulled into World War II after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and would later avenged its defeat in the Philippines with the invasion of the island of Leyte in October 1944. General Douglas MacArthur, who in 1942 had famously promised to return to the Philippines, made good on his word. In February 1945, US-Filipino forces recaptured the Bataan Peninsula, and Manila was liberated in early March. After the war, an American military tribunal tried Lieutenant General Homma Masaharu, commander of the Japanese invasion forces in the Philippines. He was held responsible for the death march, a war crime, and was executed by firing squad on April 3, 1946.

America was pulled into World War II after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and would later avenged its defeat in the Philippines with the invasion of the island of Leyte in October 1944. General Douglas MacArthur, who in 1942 had famously promised to return to the Philippines, made good on his word. In February 1945, US-Filipino forces recaptured the Bataan Peninsula, and Manila was liberated in early March. After the war, an American military tribunal tried Lieutenant General Homma Masaharu, commander of the Japanese invasion forces in the Philippines. He was held responsible for the death march, a war crime, and was executed by firing squad on April 3, 1946.

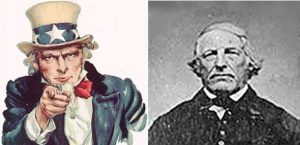

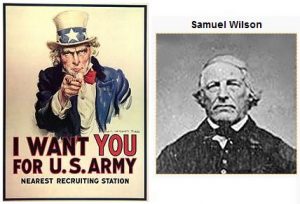

Everyone has heard the term, Uncle Sam used when referring to the United States government, but while the government and the people of the United States have “adopted” that term to mean the United States government, it was really never intended to be so. If you ask most people, the average older American would most likely point to the early 20th century and Sam’s frequent appearance on army recruitment posters. Nevertheless, the figure of Uncle Sam actually dates back much further than that. The actual figure of Uncle Sam, dates from the War of 1812. At that point, most American icons had been geographically specific, centering most often on the New England area. However, the War of 1812 sparked a renewed interest in national identity which had faded since the American Revolution.

Everyone has heard the term, Uncle Sam used when referring to the United States government, but while the government and the people of the United States have “adopted” that term to mean the United States government, it was really never intended to be so. If you ask most people, the average older American would most likely point to the early 20th century and Sam’s frequent appearance on army recruitment posters. Nevertheless, the figure of Uncle Sam actually dates back much further than that. The actual figure of Uncle Sam, dates from the War of 1812. At that point, most American icons had been geographically specific, centering most often on the New England area. However, the War of 1812 sparked a renewed interest in national identity which had faded since the American Revolution.

The term Uncle Sam was actually the nickname of a man named Samuel Wilson, who was a meat packer from Troy, New York. Sam supplied rations for the soldiers during the War of 1812. He had served in the American Revolution at the age of 15, and while he was born in Massachusetts, he relocated to the town of Troy, New York after the war. In Troy, Samuel and his brother, Ebenezer began the firm of E and S Wilson, a meat packing facility. Samuel was a man of great fairness, reliability, and honesty, who was devoted to his country. All of the local residents really liked Samuel, and they began calling him Uncle Sam.

During the War of 1812, the demand for meat supply for the troops was badly needed. Because he had been a soldier, Samuel had a soft spot in his heart for the soldiers. Secretary of War, William Eustis, made a contract with Elbert Anderson Jr of New York City to supply and issue all rations necessary for the United States forces in New York and New Jersey for one year. Anderson ran an advertisement on October 6, 1813 looking to fill the contract. The Wilson brothers bid for the contract and won. The contract was to fill 2,000 barrels of pork and 3,000 barrels of beef for one year. Their location on the Hudson River, made it ideal to receive the animals and to ship the product. As a security measure, the contractors were required to stamp their name and where the rations came from onto the food they were sending. Wilson’s packages bore the label “E.A. – US,” which stood for Elbert Anderson, the contractor, and the United States. When an individual in the meat packing facility asked what it stood for, a coworker joked and said it referred to Sam Wilson, Uncle Sam. A number of the soldiers were originally from Troy, and familiar with Samuel. When they saw the designation on the barrels, they, being acquainted with Sam Wilson and his nickname Uncle Sam, as well as the knowledge that Wilson was feeding the army, led them to the same conclusion. The local newspaper soon picked up on the story and Uncle Sam eventually gained widespread acceptance as the nickname for the U.S. federal government.

This is, of course, an endearing local story, and therefore, leaves some doubt as to whether it is the actual source of the term. Uncle Sam is mentioned previous to the War of 1812 in the popular song “Yankee Doodle,” which appeared in 1775. Nevertheless, the song doesn’t make it clear whether this reference is to Uncle Sam as a metaphor for the United States, or to an actual person named Sam. Another early reference to the term appeared in 1819, predating Wilson’s contract with the government. The connection between this local saying and the national legend is not easily traced. As early as 1830, there were inquiries into the origin of the term Uncle Sam. The connection between the popular cartoon figure and Samuel Wilson was reported in the New York Gazette on May 12, 1830. Whatever the source, Uncle Sam immediately became popular as a symbol of an ever-changing nation. His “likeness” appeared in drawings in various forms including resemblances to Brother Jonathan, a national personification and emblem of New England, and Abraham Lincoln, and others. In the late 1860s and 1870s, a political cartoonist named Thomas Nast began popularizing the image of Uncle Sam…building on the warm fuzzy feel of a beloved uncle. Nast continued to evolve the image, eventually giving Sam the white beard and stars-and-stripes suit that are associated with the character today.

However, it was a military recruiting poster, created in about 1917, that set the image of Uncle Sam was firmly set into American consciousness. The famous “I Want You” recruiting poster was created by James Montgomery Flagg and four million posters were printed between 1917 and 1918. The image was a really powerful one:  Uncle Sam’s striking features, expressive eyebrows, pointed finger, and direct address to the viewer made this drawing into an American icon. Throughout the years, Uncle Sam has appeared in advertising and on products ranging from cereal to coffee to car insurance. His likeness also continued to appear on military recruiting posters and in numerous political cartoons in newspapers. Finally, in September of 1961, the U.S. Congress recognized Samuel Wilson as “the progenitor of America’s national symbol of Uncle Sam.” Samuel Wilson died at age 88 in 1854, and was buried next to his wife Betsey Mann in the Oakwood Cemetery in Troy, New York. The town proudly calls itself “The Home of Uncle Sam.”

Uncle Sam’s striking features, expressive eyebrows, pointed finger, and direct address to the viewer made this drawing into an American icon. Throughout the years, Uncle Sam has appeared in advertising and on products ranging from cereal to coffee to car insurance. His likeness also continued to appear on military recruiting posters and in numerous political cartoons in newspapers. Finally, in September of 1961, the U.S. Congress recognized Samuel Wilson as “the progenitor of America’s national symbol of Uncle Sam.” Samuel Wilson died at age 88 in 1854, and was buried next to his wife Betsey Mann in the Oakwood Cemetery in Troy, New York. The town proudly calls itself “The Home of Uncle Sam.”

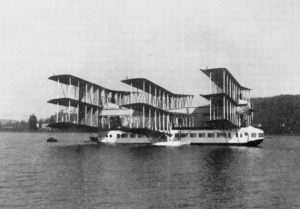

As airplanes go, we have seen many varieties over the years. Designs had to be streamlined in order to increase distance and improve fuel economy. The designs also had to provide increasing stability for longer flights, and to protect the people on board. I can understand design changes, and I know that they are necessary, but in the grand scheme of things, some of the different designs are not only strange, but downright humorous… and some were actually quite dangerous. Still, I guess everyone longs to design something new and different. Some of these planes may have had some purpose that I know nothing about, but I don’t think that many of them were very successful.

As airplanes go, we have seen many varieties over the years. Designs had to be streamlined in order to increase distance and improve fuel economy. The designs also had to provide increasing stability for longer flights, and to protect the people on board. I can understand design changes, and I know that they are necessary, but in the grand scheme of things, some of the different designs are not only strange, but downright humorous… and some were actually quite dangerous. Still, I guess everyone longs to design something new and different. Some of these planes may have had some purpose that I know nothing about, but I don’t think that many of them were very successful.

The B377PG, NASA’s Super Guppy Turbine Cargo Plane was first flown in 1980. It was nicknamed the “Pregnant Guppy” and was one of the most unique transports ever constructed. It was actually a modified Boeing 377 and it was the perfect hauler for those gigantic, weirdly shaped payloads that need to be transported cross-country in a hurry for some NASA project. It was originally commissioned by NASA to move the many components of the Apollo moon missions around. After the Apollo years, the Guppies were used  extensively by the private sector for years after the program was cancelled. To me it looks like a giant Airstream Travel trailer, and at first sight, its funny shape made me laugh.

extensively by the private sector for years after the program was cancelled. To me it looks like a giant Airstream Travel trailer, and at first sight, its funny shape made me laugh.

Another cargo plane that looked quite funny was the Short SC.7 Skyvan, which was nicknamed the “Flying Shoebox.” Manufactured by the Short Brothers in Belfast, Northern Ireland, the plane was a British 19-seat twin-turboprop aircraft. It is used for short-haul freight and skydiving. Its first flight was in January 1963. If you ask me, it barely looks like this plane could fly, but apparently it did so, quite well.

And then, there was the Caproni Ca.60 Transaereo, also known as “Capronissimo” and Noviplano Transaereo. On March 4, 1921 it tried to take off from Lake Maggiore with its nine, 30-meter-long wings. It barely seemed possible that this huge plane could win against gravity. It was similar in theme to crafts built by Icarus and Leonardo, who had already overcome gravity with hot air balloons, airships, and biplanes. I couldn’t imagine why they thought that such a monstrosity could fly, let alone land in one piece, nevertheless, Engineer Gianni  Caproni, wanted to prove that he could do it. So, with eight American 400-hp engines, 750 square meters of wings and 23 of fuselage, his gigantic hydroplane was over nine meters tall and weighed over 15,000 kilos when empty. It was designed to carry one hundred people across the Atlantic. The only problem was that the plane was simply too heave to manage a safe takeoff, much less a landing. The huge machine, with former military aviator Federico Semprini in the cabin, climbed too much in an effort to pull away from the flat waters of the lake and broke a few components, shattering Caproni’s dreams. I think it is very likely a good thing it never went further, because I’m not sure that such a frame could stand up to much windspeed.

Caproni, wanted to prove that he could do it. So, with eight American 400-hp engines, 750 square meters of wings and 23 of fuselage, his gigantic hydroplane was over nine meters tall and weighed over 15,000 kilos when empty. It was designed to carry one hundred people across the Atlantic. The only problem was that the plane was simply too heave to manage a safe takeoff, much less a landing. The huge machine, with former military aviator Federico Semprini in the cabin, climbed too much in an effort to pull away from the flat waters of the lake and broke a few components, shattering Caproni’s dreams. I think it is very likely a good thing it never went further, because I’m not sure that such a frame could stand up to much windspeed.

We have all made mistakes, but thankfully, most of them don’t end up costing people their lives. Nevertheless, there are few mistakes that can measure up to the Battle of Karansebes. In 1788, Austria was at war with Turkey, fighting over control of the Danube River. About 100,000 Austrian troops were camped near Karansebes, which is a village that is located in what is today Romania. Scouts were sent ahead to see if they could locate any Turkish soldiers. The scouts didn’t find any evidence of Turks, but they found gypsies…who as it turns out, had a lot of alcohol to sell, and the scouts bought it.

We have all made mistakes, but thankfully, most of them don’t end up costing people their lives. Nevertheless, there are few mistakes that can measure up to the Battle of Karansebes. In 1788, Austria was at war with Turkey, fighting over control of the Danube River. About 100,000 Austrian troops were camped near Karansebes, which is a village that is located in what is today Romania. Scouts were sent ahead to see if they could locate any Turkish soldiers. The scouts didn’t find any evidence of Turks, but they found gypsies…who as it turns out, had a lot of alcohol to sell, and the scouts bought it.

After returning to camp, with the alcohol, they started drinking, thinking that the next day they would be going into battle, so why not enjoy the evening before with a party, since the best thing to do the night before a big battle is get very, very drunk. As happens with a drunken party, the revelers got very loud and quite obnoxious. The noise attracted the attention of several foot soldiers who wanted to join in. The scouts were not interested in sharing the alcohol, and being very drunk, they weren’t careful in how that told the foot soldiers that they were not welcome.

Once the argument began, it quickly escalated into a fight. The alcohol was confiscated, more men joined in the fight, punches were thrown, and a shot rang out. In the middle of the chaos, someone shouted that the Turks had arrived. Most of the soldiers fled the scene immediately, because they were unprepared for battle. Others got into formation and charged at the supposed enemy. Shots were fired, cavalry was assembled, and the defecting soldiers were killing every man they saw without thinking. Needless to say, the Turkish army had not arrived. They wandered into Karansebes two days later and found 10,000 dead or wounded Austrian soldiers. A little confused by this turn of events, they were nonetheless delighted to take Karansebes without any effort.

If you ever feel like you’ve “made a huge mistake,” just remember…it’s probably not bigger than the Battle of Karansebes. When an army mistakes its own soldiers for the enemy, and mistakenly fights and kills 10,000 men…well, that is a huge mistake!! Some people say that the Battle of Karansebes never happened, because  they can’t find any conclusive evidence to show that it happened. Seriously, if I were in charge of the Austrian Army, I might not want anyone to know of this mistake either. Still, those who believe in the battle said that the army could very easily have gotten confused. At the time, the Austrian army was made up of people who spoke German, Hungarian, Polish, and Czechoslovakian, among other languages. This resulted in a lot of confusion and miscommunication as many troops and officers weren’t able to understand each other. I can certainly see where that could bring the kind of confusion that could have cause the army to fight themselves, especially in a drunken state.

they can’t find any conclusive evidence to show that it happened. Seriously, if I were in charge of the Austrian Army, I might not want anyone to know of this mistake either. Still, those who believe in the battle said that the army could very easily have gotten confused. At the time, the Austrian army was made up of people who spoke German, Hungarian, Polish, and Czechoslovakian, among other languages. This resulted in a lot of confusion and miscommunication as many troops and officers weren’t able to understand each other. I can certainly see where that could bring the kind of confusion that could have cause the army to fight themselves, especially in a drunken state.

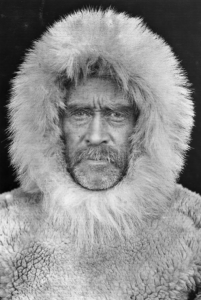

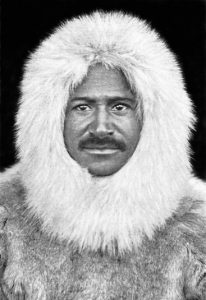

When I think of the world’s explorers, I think back to the 1500s to maybe the 1700s, but there are still explorers, and probably places that no man has ever been, and some explorations are still going on. That is most likely because some places are very difficult to reach. American explorer Robert Peary knew that all too well. Peary had a dream. He wanted to go to the North Pole. For many years one thing or another came between Peary and his dream, but finally on April 6, 1909, Peary and his assistant Matthew Henson, and four Eskimos reached what they determined to be the North Pole. I can only imagine how elated they felt. It was the journey of a lifetime for them.

When I think of the world’s explorers, I think back to the 1500s to maybe the 1700s, but there are still explorers, and probably places that no man has ever been, and some explorations are still going on. That is most likely because some places are very difficult to reach. American explorer Robert Peary knew that all too well. Peary had a dream. He wanted to go to the North Pole. For many years one thing or another came between Peary and his dream, but finally on April 6, 1909, Peary and his assistant Matthew Henson, and four Eskimos reached what they determined to be the North Pole. I can only imagine how elated they felt. It was the journey of a lifetime for them.

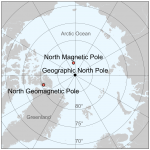

Peary, a US Navy civil engineer, made his first trip to the interior of Greenland in 1886. In 1891, Henson, a young African-American sailor, joined him on his second arctic expedition. Their team made an extended dogsled journey to the northeast of Greenland and explored what became known as “Peary Land.” Then, in 1893, they began working toward reaching the North Pole. In 1906, during their second attempt, they nearly reached latitude 88 degrees north, just 150 miles short of their objective. It would seem that they had the fever, because in 1908, they traveled to Ellesmere Island by ship and in 1909 raced across hundreds of miles of ice to reach what they calculated as latitude 90 degrees north on April 6, 1909. Although their achievement was widely acclaimed, Dr. Frederick A. Cook challenged their distinction of being the first to reach the North Pole. Cook, a former associate of Peary, claimed he had already reached the pole by dogsled the previous year. A major controversy followed, and in 1911 the US Congress formally recognized Peary’s claim over Cook’s.

Sadly, decades after Peary’s death, navigational errors in his travel log surfaced, placing the expedition in all probability a few miles short of its goal. I am glad he never knew. In recent years, further studies of the conflicting claims suggest that neither expedition reached the exact North Pole, but that Peary and Henson came far closer, falling perhaps just 30 miles short. On May 3, 1952, US Lieutenant Colonel Joseph O. Fletcher

of Oklahoma stepped out of a plane and walked to the precise location of the North Pole, the first person to undisputedly do so. While he did step on the exact location, as confirmed by GPS or whatever measurement they used to confirm the location, it is my opinion that the accomplishment of Lieutenant Colonel Fletcher was nowhere near as amazing as that of Robert Peary and his team, who forged their way to the site, rather than being dropped on it.

of Oklahoma stepped out of a plane and walked to the precise location of the North Pole, the first person to undisputedly do so. While he did step on the exact location, as confirmed by GPS or whatever measurement they used to confirm the location, it is my opinion that the accomplishment of Lieutenant Colonel Fletcher was nowhere near as amazing as that of Robert Peary and his team, who forged their way to the site, rather than being dropped on it.

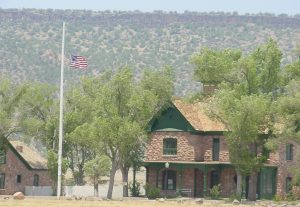

During our nation’s early years, there were many times when we found it necessary to build forts to protect the people in the area. The forts housed the armies and also took in civilians when needed. In 1870, the government built a military post four miles south of what is today, Whiteriver, Arizona. The fort was named Camp Ord, and was named after General O.C. Ord, Commander of Arizona when it was built in the spring. Just a few months later in August, the name was changed to Camp Mogollon, then Camp Thomas in September. It seems almost comical that the name would change so many times, but that was how things were done then, I guess.

During our nation’s early years, there were many times when we found it necessary to build forts to protect the people in the area. The forts housed the armies and also took in civilians when needed. In 1870, the government built a military post four miles south of what is today, Whiteriver, Arizona. The fort was named Camp Ord, and was named after General O.C. Ord, Commander of Arizona when it was built in the spring. Just a few months later in August, the name was changed to Camp Mogollon, then Camp Thomas in September. It seems almost comical that the name would change so many times, but that was how things were done then, I guess.

The post received it’s final name…Camp Apache on February 2, 1871, as a token of friendship to the Apache Indians. Ironically, the soldiers at the fort would soon spend many years at war with these same Indians they were trying to befriend. The fort’s initial purpose was to guard the nearby White Mountain Reservation and Indian agency. The fort was located at the end of a military road on the White Mountain Reservation. Right next to that was the San Carlos Agency. Both reservations would become the focus of Apache unrest, especially after troops moved the troublesome Chiricahuas from Fort Bowie to the White Mountain Reservation in 1876.

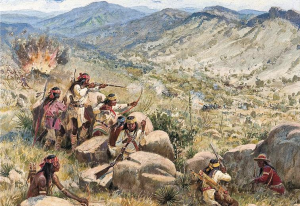

The area was in constant turmoil, mostly because the reservations were noted for their unhealthful location, overcrowded conditions, and dissatisfied inhabitants. Inefficient and corrupt agents added to the problem, and friction between civil and military authorities grew. Several attempts to turn the nomadic Indians into farmers, and an influx on the reservations of settlers and miners only added to the problem, and battles became the normal everyday event. As a result, many of the Indians left the reservations to resume their hunting, gathering, and raiding lifestyle, creating a public outcry from the settlers.

In 1871, General George Crook was named commander of the Department of Arizona. Crook had earned a reputation as an Indian fighter in the Snake War in Idaho and Oregon. Crook quickly realized that his soldiers were no match for the fierce Apache he was sent to subdue, so he made his first trip to Fort Apache. At the reservation, he recruited about fifty men to serve as Apache Scouts. These men would play a key role in the success of the Army in the Apache Wars which ensued for the next 15 years.

After recruiting the scouts, Crook prepared for his Tonto Basin campaign. Then he moved on to Camp Verde to implement his tactical operations there. During the winter of 1872-1873, Crook sent a number of mobile detachments, using Apache scouts, to crisscross the Tonto Basin and the surrounding tablelands in constant pursuit of renegade Tonto Apache and their Yavapai allies. The campaigns forcing as many as 20 skirmishes. In all some 200 Indians were killed. The battles finally began to wear down the Indians. On April 5, 1879, Camp

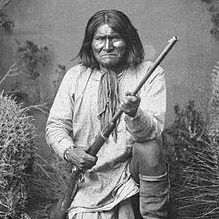

Apache had gained enough significance that it was renamed Fort Apache. The battles with the Apache continued as the soldiers fought various renegade bands that included such famous warriors as Geronimo, Natchez, Chato, and Chihuahua. It was only after Geronimo was captured for the last time in 1886, that the Apache Wars finally came to an end…and with it the need for Fort Apache. Nevertheless, it remained active until 1924. Then it was closed and the area given back to the reservation.

Apache had gained enough significance that it was renamed Fort Apache. The battles with the Apache continued as the soldiers fought various renegade bands that included such famous warriors as Geronimo, Natchez, Chato, and Chihuahua. It was only after Geronimo was captured for the last time in 1886, that the Apache Wars finally came to an end…and with it the need for Fort Apache. Nevertheless, it remained active until 1924. Then it was closed and the area given back to the reservation.

As Spring arrives, many people, including my husband Bob and I, have started thinking about the home improvement projects they want to get done. Depending on what you have in mind, it can be a few minor improvements, or it can be big projects, like room gut-jobs and remodels. Whatever it is, you can count on it being work, because no home improvement project is easy. Still, I wonder if we would consider our own home improvement projects to be a daunting a task as the one that took place on the Woolworth building in New York City.

As Spring arrives, many people, including my husband Bob and I, have started thinking about the home improvement projects they want to get done. Depending on what you have in mind, it can be a few minor improvements, or it can be big projects, like room gut-jobs and remodels. Whatever it is, you can count on it being work, because no home improvement project is easy. Still, I wonder if we would consider our own home improvement projects to be a daunting a task as the one that took place on the Woolworth building in New York City.

Retailer Frank W. Woolworth commissioned the building in 1910, which he would name  after himself. This was just a year after the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company moved into their 700-foot tower on Madison Square, just a block away from the triangle-shaped Flatiron Building. The Metropolitan Life Tower had become the world’s tallest building at that time, having taken over that title from the New York headquarters of the Singer Sewing Machine Company, completed in 1908. Of course, as buildings go and builders follow, the latest “tallest building in the world” is nothing more than a challenge to see who will build the next building to beat the record set by the last building in the category.

after himself. This was just a year after the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company moved into their 700-foot tower on Madison Square, just a block away from the triangle-shaped Flatiron Building. The Metropolitan Life Tower had become the world’s tallest building at that time, having taken over that title from the New York headquarters of the Singer Sewing Machine Company, completed in 1908. Of course, as buildings go and builders follow, the latest “tallest building in the world” is nothing more than a challenge to see who will build the next building to beat the record set by the last building in the category.

Building a super structure is difficult enough, to be sure, but what about when such a structure need something like, a outside paint job. The reality is that it was going to take some great painters…who were very brave, and hopefully, not afraid of heights. This was no ordinary job. Now, I love hiking, and I have been to the top of a few mountains peaks, but I still don’t like being at the edge of a cliff. I have no desire to stand at the edge of a cliff and look down to see how far away it is. That makes me squeamish. Nevertheless, the brave men chosen to paint the top of the Woolworth building years ago, had to have stomachs made of cast iron, and nerves of steel. They not only went up there and painted the building, but they even found time to prove their bravery in pictures while they were there. I don’t know how OSHA would feel about the stunts they performed, but perform they did, nevertheless.

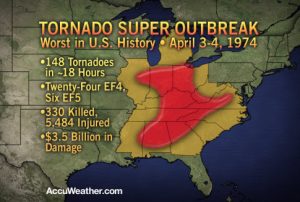

We all know that tornadoes are possible just about anywhere in the world…but in the United States, in an area well known as Tornado Alley, tornadoes are a common thing during tornado season, and sometimes outside of tornado season. Tornado Alley gets an average of more than 1,000 tornadoes a year, but on April 3, 1974, a super outbreak began. Over a less than 18 hour span, 148 tornadoes touched down across 13 states, with 21 in Indiana. The tornadoes hit North America from Georgia to Canada within 16 hours. At times there were as many as 15 separate tornadoes on the ground at one time. The Super Outbreak affected a total of 11 US states and Ontario in Canada. The Monticello tornado, which occurred during the weather event, tracked a whopping 121 miles, he longest tornado track in Indiana history! The 1974 tornado outbreak held the record as the largest outbreak in US history, killing 330 people…until the 2011 tornado outbreak, during which 360 tornadoes touched down killing 337 people.

We all know that tornadoes are possible just about anywhere in the world…but in the United States, in an area well known as Tornado Alley, tornadoes are a common thing during tornado season, and sometimes outside of tornado season. Tornado Alley gets an average of more than 1,000 tornadoes a year, but on April 3, 1974, a super outbreak began. Over a less than 18 hour span, 148 tornadoes touched down across 13 states, with 21 in Indiana. The tornadoes hit North America from Georgia to Canada within 16 hours. At times there were as many as 15 separate tornadoes on the ground at one time. The Super Outbreak affected a total of 11 US states and Ontario in Canada. The Monticello tornado, which occurred during the weather event, tracked a whopping 121 miles, he longest tornado track in Indiana history! The 1974 tornado outbreak held the record as the largest outbreak in US history, killing 330 people…until the 2011 tornado outbreak, during which 360 tornadoes touched down killing 337 people.

The outbreak began when a powerful low pressure system developed on April 1st, across the North American Interior Plains. As it moved into the Mississippi and Ohio Valley areas, a surge of very humid air intensified the storm further, and there were sharp temperature differences between both sides of the system. The National Weather Service began forecasting a severe weather outbreak on April 3, but no one expected the severity of the outbreak that actually occurred. Several F2 and F3 tornadoes struck portions of the Ohio Valley and the South in a separate, earlier outbreak on April 1 and 2, which included three killer tornadoes in Kentucky, Alabama, and Tennessee. The town of Campbellsburg, northeast of Louisville, was hard-hit in this earlier outbreak, with a large portion of the town destroyed by an F3. Between the two outbreaks, an additional tornado was reported in Indiana in the early morning hours of April 3, several hours before the official start of the outbreak. On Wednesday, April 3, severe weather watches already were issued from the morning from south of the Great Lakes, while in portions of the Upper Midwest, snow was reported, with heavy rain falling  across central Michigan and much of Ontario, which also had tornadoes.

across central Michigan and much of Ontario, which also had tornadoes.

Perhaps the most shocking fact from the 1974 outbreak was the amount of F4 and F5 tornadoes…with an incredible 30 (23 F4s and 7 F5s). The 1974 outbreak featured 30 violent tornadoes in less than one day when the national average is only about 7 per year. All seven of the F5 tornadoes occurred on the 3rd, and Alabama was the state that experienced the highest number of F5 tornadoes that day…three out of seven. The other F5 tornadoes occurred throughout Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio. these super outbreaks are some of the most shocking weather phenomena ever.

For a time, bombs or bomb threats seemed to be the weapon of choice for terrorists and hijackers on the worlds airlines. With better screenings and luggage checks, things have improved and we see fewer incidences like these, but that in no way means that we should ever let our guard down, because evil exists in this world, and awareness of that fact saves lives. On April 2, 1986, we weren’t quite as prepared as we are today. On that day, Trans World Airlines Flight 840 was on a regularly scheduled flight from Los Angeles to Cairo via New York City, Rome, and Athens. The plane was flying at 11,000 feet over Greece, on its way to Athens, when the bomb went off. Four people, including an eight-month old baby, were sucked out of a TWA passenger jet after an explosion ripped a hole in its side.

For a time, bombs or bomb threats seemed to be the weapon of choice for terrorists and hijackers on the worlds airlines. With better screenings and luggage checks, things have improved and we see fewer incidences like these, but that in no way means that we should ever let our guard down, because evil exists in this world, and awareness of that fact saves lives. On April 2, 1986, we weren’t quite as prepared as we are today. On that day, Trans World Airlines Flight 840 was on a regularly scheduled flight from Los Angeles to Cairo via New York City, Rome, and Athens. The plane was flying at 11,000 feet over Greece, on its way to Athens, when the bomb went off. Four people, including an eight-month old baby, were sucked out of a TWA passenger jet after an explosion ripped a hole in its side.

It blew a hole six feet by three feet wide under a window in front of the starboard wing. It is believed the explosion happened at floor level in the passenger compartment itself. The four bodies of the victims were retrieved from a site 87 miles southwest of Athens. Three were from the same Greek-American family, believed to have been a grandmother, her daughter and her granddaughter. Police also found the body of a male passenger identified as a Colombian-born American, sucked out of the plane still in his seat. Remarkably, the remaining 118 passengers and crew survived, including Christian author, Jeanette Chaffee, who has written about this and other incredible situations, called “Extravagant Graces,” a book I think I will have to read. The pilot, Captain Richard Petersen, made an emergency landing, telling Athens control tower that the pressurization in the cabin was failing.

The pilot, Captain Richard Petersen, made an emergency landing, telling Athens control tower that the pressurization in the cabin was failing. He is being hailed as a hero. “We are proud of him,” said a TWA source. Just seven passengers were taken to hospital, and only three were kept in for treatment. One was Ibrahim al-Nami, from Saudi Arabia, who said he had been sitting next to the man who was sucked out with his seat. “We heard a big bang outside the window,” he said,” and then I saw the man next to me disappear and I felt myself being pulled out.” He avoided sharing the same fate by clinging on to his wife’s seat. Another passenger escaped because she left her seat only minutes earlier to go to the lavatory. Florentia Haniotakis, a Greek-American from Ohio, praised the crew. She says they comforted passengers to calm them during the emergency landing.

The airliner was on the same Rome-Cairo route as a similar TWA plane hijacked by Shia Muslim gunmen in June 1985 after leaving Athens for Rome. The investigation found that the bomb had been planted under seat number 10F, probably inside a lifejacket. A group calling itself the Ezzedine Kassam Unit of the Arab Revolutionary Cells claimed responsibility, and said the bombing was in retaliation for US bombing raids against  Libya the previous month. Police initially suspected a Lebanon-born Palestinian woman named Mai Elias Mansur. Mansur was a suspected terrorist connected with the Abu Nidal extremist group, who was involved in an abortive attempt to bomb a Pan American airliner in 1983. She had travelled in seat 10F on an earlier flight of the same Boeing 727. Mansur denied any involvement. After a two year investigation, the US State Department said it believed that she had carried out the bombing, operating on the orders of known Palestinian terrorist Colonel Hawari, but they were unable to definitively prove it. Therefore, nobody has ever been convicted of carrying out the bombing. TWA filed for bankruptcy in 2001 and was taken over by American Airlines.

Libya the previous month. Police initially suspected a Lebanon-born Palestinian woman named Mai Elias Mansur. Mansur was a suspected terrorist connected with the Abu Nidal extremist group, who was involved in an abortive attempt to bomb a Pan American airliner in 1983. She had travelled in seat 10F on an earlier flight of the same Boeing 727. Mansur denied any involvement. After a two year investigation, the US State Department said it believed that she had carried out the bombing, operating on the orders of known Palestinian terrorist Colonel Hawari, but they were unable to definitively prove it. Therefore, nobody has ever been convicted of carrying out the bombing. TWA filed for bankruptcy in 2001 and was taken over by American Airlines.