History

These days we don’t usually think much about trains as a form of transportation, but in 1869, they were the latest in modern travel. The United States is a large country, and it took months to travel across it with a horse drawn wagon. Travel was so time consuming, that most people could not take the necessary time off from their jobs and lives to go to visit family that had moved west, or those who stayed in the east. Enter the train.

These days we don’t usually think much about trains as a form of transportation, but in 1869, they were the latest in modern travel. The United States is a large country, and it took months to travel across it with a horse drawn wagon. Travel was so time consuming, that most people could not take the necessary time off from their jobs and lives to go to visit family that had moved west, or those who stayed in the east. Enter the train.

Trains could take people to far away destinations much faster, and cheaper…but there was still one problem…train tracks. The trains could only go as far as the tracks did, and the work of building tracks was a back breaking job. Nevertheless, 150 years ago, on this day, May 10, 1869, the presidents of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads meet in Promontory, Utah. There they drove a ceremonial last spike into a rail line that connects their railroads. This made transcontinental railroad travel possible for the first time in United States history.

Now 150 years later, on of the trains that rode those rails in those days is back on the rails. The locomotives were called “Big Boys” and they certainly were. “It’s longer than two city buses, weighs more than a Boeing 747 fully loaded with passengers and can pull 16 Statues of Liberty over a mountain.” The refurbished Big Boy is the number 4014 steam locomotive that rolled out of a Union Pacific restoration shop in Cheyenne this past weekend for a big debut after five years of restoration. It then headed toward Utah as part of a yearlong tour to commemorate the Transcontinental Railroad’s 150th anniversary. If you have a chance, I would highly recommend that you get a copy of the schedule and plan to go see it. We are planning to, for sure.

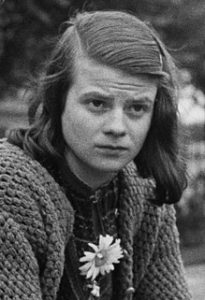

When we think of heroes during the Nazi years, we think mostly of men, but there were a few women who were real heroes too. One such woman, Sophia Magdalena Scholl, who was born on May 9, 1921, was a German student, who was also a serious anti-Nazi political activist. She was active within the White Rose non-violent resistance group in Nazi Germany. Scholl was the fourth of six children born to Magdalena (Müller) and liberal politician and ardent Nazi critic Robert Scholl. Her father was the mayor of her hometown of Forchtenberg am Kocher in the Free People’s State of Württemberg, at the time of her birth.

When we think of heroes during the Nazi years, we think mostly of men, but there were a few women who were real heroes too. One such woman, Sophia Magdalena Scholl, who was born on May 9, 1921, was a German student, who was also a serious anti-Nazi political activist. She was active within the White Rose non-violent resistance group in Nazi Germany. Scholl was the fourth of six children born to Magdalena (Müller) and liberal politician and ardent Nazi critic Robert Scholl. Her father was the mayor of her hometown of Forchtenberg am Kocher in the Free People’s State of Württemberg, at the time of her birth.

Scholl was brought up in the Lutheran church. She entered junior or grade school at the age of seven, and was considered an intelligent child who learned easily. Her childhood was a happy and carefree one. In 1930, the family moved to Ludwigsburg and then two years later to Ulm where her father had a business consulting office. These were definitely the best years of her life.

In 1932, after Scholl started attending a secondary school for girls, at the age of twelve, she chose to join the Bund Deutscher Mädel (League of German Girls), as did most of her classmates. It was as common as joining the girl scouts was in the United States. Her initial enthusiasm gradually gave way to criticism. She was aware of the dissenting political views of her father, friends, and some teachers. Even her own brother Hans, who once eagerly participated in the Hitler Youth program, became entirely disillusioned with the Nazi Party. Sophia was quickly learning of the horrors of Hitler and his Nazi regime. Political attitude had become an essential criterion in her choice of friends. The arrest of her brothers and friends in 1937 for participating in the German Youth Movement left a strong impression on her.

In 1943, with the Nazi movement in full swing, Sophia and her brother, Hans were at the University of Munich distributing anti-war leaflets when they were arrested and charged with high treason. Of course, handing out  anti-war leaflets in the United States would never be considered cause for a high treason conviction, but then Sophia and her brother did not live in the United States. In the People’s Court before Judge Roland Freisler on 22 February 1943, Scholl was recorded as saying these words, “Somebody, after all, had to make a start. What we wrote and said is also believed by many others. They just don’t dare express themselves as we did.” There was no testimony allowed for the defendants; this was their only defense. The brother and sister were subsequently convicted of the high treason charges, and as a result, were executed by guillotine on February 22, 1943. Since the 1970s, Scholl has been extensively commemorated for her anti-Nazi resistance work.

anti-war leaflets in the United States would never be considered cause for a high treason conviction, but then Sophia and her brother did not live in the United States. In the People’s Court before Judge Roland Freisler on 22 February 1943, Scholl was recorded as saying these words, “Somebody, after all, had to make a start. What we wrote and said is also believed by many others. They just don’t dare express themselves as we did.” There was no testimony allowed for the defendants; this was their only defense. The brother and sister were subsequently convicted of the high treason charges, and as a result, were executed by guillotine on February 22, 1943. Since the 1970s, Scholl has been extensively commemorated for her anti-Nazi resistance work.

It was a time when the race across the Atlantic Ocean was a big as the Race to Space would become years later. Since the invention of planes, everyone trained as a pilot wanted to set some sort of record in the aviation industry, and there were plenty of them out there to set. One in particular, the transatlantic flight was in its early stages. The world was waiting for that first successful transatlantic non-stop flight.

It was a time when the race across the Atlantic Ocean was a big as the Race to Space would become years later. Since the invention of planes, everyone trained as a pilot wanted to set some sort of record in the aviation industry, and there were plenty of them out there to set. One in particular, the transatlantic flight was in its early stages. The world was waiting for that first successful transatlantic non-stop flight.

Then on May 8, 1927, it looked like all that would change. That morning French aviator, Captain Charles Nungesser and his co-pilot, Francis Coli took off from Paris in a plane they called The White Bird, to the surprise of many observers who felt the weather conditions were not favorable. Nevertheless, the White Bird taxied down the runway at 5:17 am on that Sunday morning, bound for New York. The plane rose and faltered, and after rolling half a mile it finally labored into the air. As it disappeared in the distance, it was no more than 700 feet off the ground when. Less than five hours later the White Bird was sighted leaving the Irish coast on its way westward over the Atlantic. It looked as if all was going well.

The Bi-Plane was later spotted in the early morning off Nova Scotia fighting strong head winds and heading for the Maine Seaboard. It had been in the air for approximately 33 hours. Shortly after the sighting the plane mysteriously disappeared while trying to be the first to complete the non-stop transatlantic flight, flying from Paris to New York City. On the afternoon of May 9, 1927, Anson Berry, fishing in his canoe on Round Lake in eastern Maine, heard what sounded like an engine overhead, approaching from the northeast. He could not see the airplane, if that was what it was, because of a heavy overcast. He assumed that it was the White Bird, because there weren’t many planes flying in those days.

The engine sounded erratic. Moments later it stopped, and Berry heard what he described years later as a faint,  ripping crash. The afternoon was wearing on, and the always unsteady spring weather was worsening, with rain beginning to fall. Perhaps because he did not trust the weather to hold, Berry did not investigate what he heard. The plane, pilot and navigator have never been seen since and two weeks later American aviator Charles Lindbergh, flying solo, successfully crossed from New York to Paris. Many people wondered why no one had ever happened upon the wreck, but the probable area of the crash is in an area of heavy underbrush, and it is likely that the wreck has been buried in the foliage.

ripping crash. The afternoon was wearing on, and the always unsteady spring weather was worsening, with rain beginning to fall. Perhaps because he did not trust the weather to hold, Berry did not investigate what he heard. The plane, pilot and navigator have never been seen since and two weeks later American aviator Charles Lindbergh, flying solo, successfully crossed from New York to Paris. Many people wondered why no one had ever happened upon the wreck, but the probable area of the crash is in an area of heavy underbrush, and it is likely that the wreck has been buried in the foliage.

In the year 1840, there was no such thing as the Fujita Scale, so when Natchez, Mississippi was hit by an F4 or F5 tornado on May 7, 1840, nobody knew its exact size, just that it was big…very big. Natchez in 1840 was a typical southern river town, reminiscent of the pre-Civil War days of slave labor and plantation wealth. Many people believed that nothing in their little part of the world could possibly change, and certainly not because of the weather. This was the context into which this tornado was about to enter…screaming violently.

In the year 1840, there was no such thing as the Fujita Scale, so when Natchez, Mississippi was hit by an F4 or F5 tornado on May 7, 1840, nobody knew its exact size, just that it was big…very big. Natchez in 1840 was a typical southern river town, reminiscent of the pre-Civil War days of slave labor and plantation wealth. Many people believed that nothing in their little part of the world could possibly change, and certainly not because of the weather. This was the context into which this tornado was about to enter…screaming violently.

May 7th started out hot and muggy, with overcast skies. The clouds were thick and most of that morning they produced continual rumblings of thunder. One resident recalled that the temperatures were in the mid-60s. Nothing about the day led anyone to believe that they were in eminent danger. And of course, at that time, there were no warning sirens, so the day dragged lazily along. At about 2 pm, the sky darkened so much that candles were needed to finish the mid-day meal that many were eating. The tornado touched down about 20 miles southwest of Natchez and moved in a northeasterly direction. It is believed that the tornado was rain-wrapped, because residence described it as “black masses, some stationary and some whirling” but the storm caused “no particular alarm” amongst the residents of Natchez. Most of the residents who weren’t eating dinner, were working down by the river. Dr Henry Tooley noted that the barometer began to fall rapidly, followed by the rain and then the tornado.

At about 2:10 pm the tornado screamed into Natchez. It lasted about three to five minutes, but the storm itself lasted about 30 minutes before it blew itself out of town. The damage path was about 10 miles long, and was estimated to be between one and two miles wide. For a time, it followed the Mississippi River hitting the southern and eastern edges of the town of Vidalia. Then the tornado crossed the river and continued on into Natchez. The town of Natchez was virtually wiped of the map, and the people on boats on the river were in serious trouble. Most of the boats on the river were flatboats, which were large rafts that carried goods on one-way trips down to New Orleans to be sold. Of the 120 flatboats docked at Natchez, 116 of them sunk. The unofficial estimated death toll was that as many as 200 people drowned after being tossed from their flatboats. It was said that “during the tornado the water rose between 10 and 15 feet, and that the water was whipped to such an extent where even a experienced swimmer could not sustain themselves on the surface.” There were also steamers one of which, The Prairie was ironically filled with a cargo of lead at the time. It sunk, of course. The steamer Hinds was badly damaged but did not sink. Its lifeless remains floated down the river to Baton Rouge where 51 bodies were found aboard.

It was really hard to establish an accurate death count, because most of the people on the river in Natchez  were not from Natchez. Most of the bodies that were found…those which were not lost after they floated out to sea…were unable to be identified because no-one knew who they were or where they came from. Lloyd’s Steamboat Disasters lists the number of lives lost that day at around 4004. In reality, this number was likely way off. This was a significant tornado, however damage also occurred above the river, in Natchez itself. The death toll may have also been skewed because in those days, the slaves were not always counted in census or death tolls. Either way, the Natchez tornado of 1840 ranks as the second most deadly tornado in US history, behind the Tri-State Tornado of 1925.

were not from Natchez. Most of the bodies that were found…those which were not lost after they floated out to sea…were unable to be identified because no-one knew who they were or where they came from. Lloyd’s Steamboat Disasters lists the number of lives lost that day at around 4004. In reality, this number was likely way off. This was a significant tornado, however damage also occurred above the river, in Natchez itself. The death toll may have also been skewed because in those days, the slaves were not always counted in census or death tolls. Either way, the Natchez tornado of 1840 ranks as the second most deadly tornado in US history, behind the Tri-State Tornado of 1925.

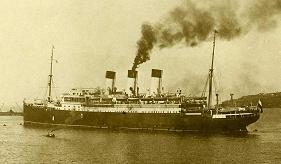

The leaders of wars have long been known for their means of deception. They will try whatever they can to confuse the enemy, and thus make their own troops safer. It all seems like a good idea, until it all goes wrong. Such was the case when, during World War I, the British army decided to disguise a passenger ship…the RMS Carmania into a battleship disguised as another passenger ship…the German SMS Trafalgar.

The leaders of wars have long been known for their means of deception. They will try whatever they can to confuse the enemy, and thus make their own troops safer. It all seems like a good idea, until it all goes wrong. Such was the case when, during World War I, the British army decided to disguise a passenger ship…the RMS Carmania into a battleship disguised as another passenger ship…the German SMS Trafalgar.

Now that all seems like a good plan, provided that you don’t run into the real SMS Trafalgar…or someone who knows where the real SMS Trafalgar is at that moment. The plan was working well, and the RMS Carmania/SMS Trafalgar seemed a great success. The only problem was that the Germans had the same idea. They decided to disguise the SMS Trafalgar as the RMS Carmania. It is odd that each side chose the ship that the other had disguised, and when you think about it, it was clearly a recipe for disaster. It was only a matter of time before the two ships would run into each other, each knowing that the other was an imposter, but not knowing that their enemy knew the same thing.

The unavoidable encounter came on September 14, 1914. A fierce battle ensued, and in the end, it was the SMS Trafalgar turned RMS Carmania that would ultimately lose this battle. In all, 51 men were killed and 279 injured from the real SMS Trafalgar, while the real RMS Carmania suffered just 9 losses. The SMS Trafalgar was also lost in the encounter. While the real RMS Carmania suffered repairable damage. The battle and ultimate sinking of the SMS Trafalgar took place off the coast of Brazil. I find it quite ironic that each ship was trying to hide in plain sight, and ended up in a battle with the very ship it was disguised to look like.

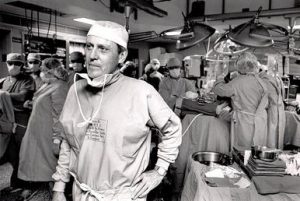

These days, organ transplants are a fairly common event. It’s not that everyone is having them, but that many people who need one get it. Years ago, something like a failing liver was an instant death sentence. The doctors would try to find a way to heal the liver, but they knew that it was not likely to happen. I know that it was heartbreaking for the doctors, who became doctors to save lives, not to lose them.

These days, organ transplants are a fairly common event. It’s not that everyone is having them, but that many people who need one get it. Years ago, something like a failing liver was an instant death sentence. The doctors would try to find a way to heal the liver, but they knew that it was not likely to happen. I know that it was heartbreaking for the doctors, who became doctors to save lives, not to lose them.

The real game changer came in 1963, when Dr Thomas E Starzl of Denver, Colorado, performed the first successful liver transplant in history. The patient was a 48 year old man. Unfortunately, he only lived for 22 day, but in those 22 days, a door was opened. Yes, there were problems, and the patient died, but he also lived…with a liver that wasn’t originally his. That was a huge step in the transplant game, and because of that step, Starzl became known as “the father of modern transplantation.”

Between March 1 and October 4, 1963, Starzl attempted 5 human liver replacements. The first patient bled to death during the operation. The other 4 died after 6.5 to 23 days. The autopsies didn’t show rejection, but rather that the patients died of site infections. During this time, there were also single attempts at transplant,  Francis D. Moore in September 1963 in Boston, and Demirleau in January 1964 in Paris. None were considered successful, but as I said. I would disagree, because while the patients died, they also lived. At this point, liver transplants on humans stopped until the summer of 1967. The operation was thought to be too difficult to ever be tried again, but Starzl refused to give up, and in 1967, he performed the first successful human liver transplant, at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center. This one would be even be considered a success by Starzl. He had also performed the world’s first spleen transplant four months earlier in the same year. After that, transplants became everyday operations.

Francis D. Moore in September 1963 in Boston, and Demirleau in January 1964 in Paris. None were considered successful, but as I said. I would disagree, because while the patients died, they also lived. At this point, liver transplants on humans stopped until the summer of 1967. The operation was thought to be too difficult to ever be tried again, but Starzl refused to give up, and in 1967, he performed the first successful human liver transplant, at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center. This one would be even be considered a success by Starzl. He had also performed the world’s first spleen transplant four months earlier in the same year. After that, transplants became everyday operations.

The Neuengamme concentration camp was established in December 1938, and used by the Nazis as a forced labor camp from December 13, 1938 to May 4, 1945, when it was liberated by British troops. At the time of its liberation, about half of the approximately 106,000 Jews held there over time had died. Neuengamme was located on the Elbe river, near Hamburg, Germany. One hundred inmates who were transferred from Sachsenhausen concentration camp, were forced to build the Neuengamme concentration camp. It was established around an empty brickworks in Hamburg-Neuengamme. The bricks produced there were to be used for the “Fuehrer buildings” part of the National Socialists’ redevelopment plans for the river Elbe in Hamburg.

The Neuengamme concentration camp was established in December 1938, and used by the Nazis as a forced labor camp from December 13, 1938 to May 4, 1945, when it was liberated by British troops. At the time of its liberation, about half of the approximately 106,000 Jews held there over time had died. Neuengamme was located on the Elbe river, near Hamburg, Germany. One hundred inmates who were transferred from Sachsenhausen concentration camp, were forced to build the Neuengamme concentration camp. It was established around an empty brickworks in Hamburg-Neuengamme. The bricks produced there were to be used for the “Fuehrer buildings” part of the National Socialists’ redevelopment plans for the river Elbe in Hamburg.

The prisoners worked on the construction of the camp and brickmaking. The bricks were used for regulating the flow of the Dove-Elbe river and the building of a branch canal. The prisoners were also  used to mine the clay used to make the bricks. That reminds me of the Jews in Egypt who were forced to build the pyramids. In 1940, the population of the camp was 2,000 prisoners, with a proportion of 80% German inmates among them. Between 1940 and 1945, more than 95,000 prisoners were incarcerated in Neuengamme. On April 10th, 1945, the number of prisoners in the camp itself was 13,500. Over the years that Neuengamme was open, it is estimated that 103,000 to 106,000 people were held there. We may never really know, because they didn’t keep clear records of all the people who went through the camps.

used to mine the clay used to make the bricks. That reminds me of the Jews in Egypt who were forced to build the pyramids. In 1940, the population of the camp was 2,000 prisoners, with a proportion of 80% German inmates among them. Between 1940 and 1945, more than 95,000 prisoners were incarcerated in Neuengamme. On April 10th, 1945, the number of prisoners in the camp itself was 13,500. Over the years that Neuengamme was open, it is estimated that 103,000 to 106,000 people were held there. We may never really know, because they didn’t keep clear records of all the people who went through the camps.

From 1942 on, the inmates were forced to work in the Nazi armament production. At first, the work was performed in the Neuengamme workshops, but soon it was decided to transfer the prisoners to the armaments factories in the surroundings areas. At the end of the war, the prisoners of Neuengamme were spread all over northern Germany. As the Allied troops advanced, hundreds of inmates were forced to dig antitank ditches. In many large north German cities, The prisoners were also require to clear rubble and removed corpses after bombing raids. There were 96 sub-camps, 20 of them for women. In early spring 1945, more than 45,000 inmates were working for the Nazi industry. A third of the women were forced to be among a part of the Nazi  industry workforce. By this time, the internal population of Neuengamme was 13,500, which made it completely overcrowded. The estimated number of victims in Neuengamme is approximately 56,000. Thousands of inmates were hanged, shot, gassed, killed by lethal injection or transferred to the death camps Auschwitz and Majdanek. As the war neared its end, the SS decided to evacuate Neuengamme. They had hoped to avoid having them liberated…probably hoping to regroup further north. This was the start of one of the worst death marches of the war. During these death marches, approximately 10,000 inmates perished by shootings or simply starvation. Nevertheless, the Allies won this war, and then they went in and liberated the prisoners of the many death camp.

industry workforce. By this time, the internal population of Neuengamme was 13,500, which made it completely overcrowded. The estimated number of victims in Neuengamme is approximately 56,000. Thousands of inmates were hanged, shot, gassed, killed by lethal injection or transferred to the death camps Auschwitz and Majdanek. As the war neared its end, the SS decided to evacuate Neuengamme. They had hoped to avoid having them liberated…probably hoping to regroup further north. This was the start of one of the worst death marches of the war. During these death marches, approximately 10,000 inmates perished by shootings or simply starvation. Nevertheless, the Allies won this war, and then they went in and liberated the prisoners of the many death camp.

It was during the Battle of the Bulge in World War II, that a B-24J plane that had been dubbed the Tulsamerican went down in the waters off of Croatia on December 17, 1944. Piloted by Army Air Forces 1st Lieutenant Eugene P. Ford, the Tulsamerican carried a crew of nine servicemen. The Tulsamerican was the lead aircraft in a group of six B-24s from the squadron to participate in a combat bombing mission targeting oil refineries at Odertal, Germany. Ford was a member of the 765th Bombardment Squadron, 461st Bombardment Group, 15th Air Force.

It was during the Battle of the Bulge in World War II, that a B-24J plane that had been dubbed the Tulsamerican went down in the waters off of Croatia on December 17, 1944. Piloted by Army Air Forces 1st Lieutenant Eugene P. Ford, the Tulsamerican carried a crew of nine servicemen. The Tulsamerican was the lead aircraft in a group of six B-24s from the squadron to participate in a combat bombing mission targeting oil refineries at Odertal, Germany. Ford was a member of the 765th Bombardment Squadron, 461st Bombardment Group, 15th Air Force.

During a bombing run on December 17, 1944, the Tulsamerican was badly damaged. Ford and his crew, aboard the Tulsamerican were assigned to be the lead aircraft in a group of six B-24s from the squadron participating in a combat bombing mission targeting oil refineries at Odertal, Germany. As they came out of a cloud bank near the target, the squadron was attacked by more than 40 German Me-109 and FW-190 fighters. The unit suffered heavy losses. Three of their six aircraft were shot down and the other three damaged.

The Tulsamerican suffered heavy damage, and they knew they would not make it back to base. The only option  for a possible forced landing was the Isle of Vis in the Adriatic Sea in what is now Croatia. Landing a B-24J on the Isle of Vis was next to impossible, but Ford knew he had to try. Unfortunately, they couldn’t quite make it to the Isle of Vis, and ended up crashing into the Adriatic Sea. Seven of Ford’s crewmembers survived and were rescued, but three, including Ford, were killed in the crash, and their bodies were unable to be recovered.

for a possible forced landing was the Isle of Vis in the Adriatic Sea in what is now Croatia. Landing a B-24J on the Isle of Vis was next to impossible, but Ford knew he had to try. Unfortunately, they couldn’t quite make it to the Isle of Vis, and ended up crashing into the Adriatic Sea. Seven of Ford’s crewmembers survived and were rescued, but three, including Ford, were killed in the crash, and their bodies were unable to be recovered.

As most of us know, military men and women do not like to leave a man behind. Nevertheless, at the time, they were unable to recover the three missing men, and they were officially listed as MIA. Ford left behind an infant daughter and his 21-year-old widow, Marian McMillen Ford, who was pregnant with their son, Richard Stanton Ford. For years it seemed that Ford would never be recovered and laid to rest, but in July of 2017, his remains and his gold wedding band were recovered during a 19 day international scientific mission. Through DNA testing at the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency’s forensic anthropology lab in Hawaii, Ford’s remains were finally identified, and his family had closure.

It was decided that ford would be buried in Arlington Cemetery. Ford’s only surviving child, 74 year-old Norma Ford Beard, traveled from her home near Indianapolis to attend the ceremony. She said her brother, Richard, who retired from the Navy after 20 years with two tours of duty in Vietnam, developed a keen interest in his father’s fate before he died in 2008. “He asked me if they ever found our father that I would see that he be buried at Arlington. I promised him that,” Beard said. Now Ford is buried next to the son he never got to meet. A very fitting place, if you ask me. Two honorable men laid to rest side by side…finally.

There was, during the Second World War, a somewhat strange and almost morbid plan that was concocted to dupe the Germans into believing that the Allies were going to invade Greece in 1943, when in fact, they were going to invade Sicily, some 500 miles away. The success of the mission really depended on the element of surprise, and in the end, the Allies needed something that would be believable to the Germans.

There was, during the Second World War, a somewhat strange and almost morbid plan that was concocted to dupe the Germans into believing that the Allies were going to invade Greece in 1943, when in fact, they were going to invade Sicily, some 500 miles away. The success of the mission really depended on the element of surprise, and in the end, the Allies needed something that would be believable to the Germans.

The thing that made the operation morbid was that in the end, they would use a dead body to bring about their deception. In their plan a body was dumped in the sea, to be discovered by Axis forces, carrying fake secret documents suggesting the invasion would be staged in Greece. They were a bit shocked when their plan worked, but work it did. The German troops were diverted to Greece, and Operation Mincemeat became a huge success, but even after it was over, it remained a source of secrecy, confusion, and conspiracy theory. The biggest source of confusion being…just who was this man who was found floating in the ocean, and how did he really die? For most people, the operation remains a mystery to this day, but one man believes that he now knows the true identity of the man found floating in the ocean.

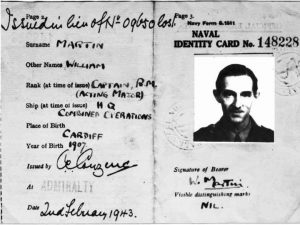

In the 1956 film called “The Man Who Never Was,” one historian claims to have finally established beyond any reasonable doubt the identity of the person who played the part of the dead man, He believes he was a homeless Welshman named Glyndwr Michael. The body, which was given the identity of a fake Royal Marine, Major William Martin, was dropped into the sea off Spain in 1943. Winston Churchill had remarked that “Anyone but a bloody fool would know it was Sicily”, but after the tides carried Major Martin’s body into the clutches of Nazi agents, Hitler and his High Command became convinced Greece was the target. “You can forget about Sicily. We know it’s in Greece,” proclaimed General Alfred Jodl, head of the German supreme command operations staff.

“Mincemeat swallowed, rod, line and sinker” was the message sent to Churchill after the Allies learned the plot had worked. In recent years, there have been repeated claims that Mincemeat’s chief planner, Lieutenant Commander Ewen Montagu, was so intent on deceiving the Germans that he stole the body of a crew member from HMS Dasher, a Royal Navy aircraft carrier which exploded off the Scottish coast in March 1943, and lied to the dead man’s relatives. In 2003, a documentary based on 14 years of research by former police officer Colin  Gibbon claimed that ‘Major Martin’ was Dasher sailor Tom Martin. Then in 2004, official sanction appeared to be given to another candidate, Tom Martin’s crewmate John Melville. At a memorial service on board the current HMS Dasher, a Royal Navy patrol vessel, off the coast of Cyprus, Lieutenant Commander Mark Hill named Mr Melville as Major Martin, describing him as “a man who most certainly was”. Mr Melville’s daughter, Isobel Mackay, later told The Scotsman newspaper: “I feel very honored if my father saved 30,000 Allied lives.” I don’t suppose that we will ever know who the man really was, without exhuming his body, and that hardly seems right. Whoever he was, his family can rest assured that he saved many lives that day.

Gibbon claimed that ‘Major Martin’ was Dasher sailor Tom Martin. Then in 2004, official sanction appeared to be given to another candidate, Tom Martin’s crewmate John Melville. At a memorial service on board the current HMS Dasher, a Royal Navy patrol vessel, off the coast of Cyprus, Lieutenant Commander Mark Hill named Mr Melville as Major Martin, describing him as “a man who most certainly was”. Mr Melville’s daughter, Isobel Mackay, later told The Scotsman newspaper: “I feel very honored if my father saved 30,000 Allied lives.” I don’t suppose that we will ever know who the man really was, without exhuming his body, and that hardly seems right. Whoever he was, his family can rest assured that he saved many lives that day.

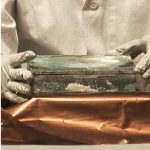

So often the past is lost because it was not preserved somehow, whether by writings, word of mouth, or in rare times it is preserved because someone put things in a time capsule to be opened at a later date. Most of us think of time capsules as a fairly modern concept, but they really aren’t. A few years ago, Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick and other dignitaries were on hand to witness the opening of one of the nation’s oldest time capsules, located in the Art of the Americas wing at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. The date was January 6, 2015. The museum’s conservator, Pam Hatchfield removed the screws from the corners of the brass box and carefully extracted its contents using tools including a porcupine quill and a dental pick that belonged to her grandfather.

So often the past is lost because it was not preserved somehow, whether by writings, word of mouth, or in rare times it is preserved because someone put things in a time capsule to be opened at a later date. Most of us think of time capsules as a fairly modern concept, but they really aren’t. A few years ago, Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick and other dignitaries were on hand to witness the opening of one of the nation’s oldest time capsules, located in the Art of the Americas wing at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. The date was January 6, 2015. The museum’s conservator, Pam Hatchfield removed the screws from the corners of the brass box and carefully extracted its contents using tools including a porcupine quill and a dental pick that belonged to her grandfather.

In December, Hatchfield had spent nearly seven hours extracting the time capsule from the cornerstone of the Massachusetts State House. The event brought with it an electrical feeling of excitement. The brass box, now green with age, measured 5.5 by 7.5 by 1.5 inches, which is a little smaller than a cigar box. It weighed 10 pounds. The contents of the time capsule were not a complete surprise, because the original time capsule had been removed in 1855, during some repairs to the building. At that time, its contents were cleaned and documented before it was placed back in the cornerstone.

More recently, workers fixing a leak unearthed the time capsule that had been placed in the building’s cornerstone more than two centuries earlier. But even after X-raying and examining the box, Hatchfield and her colleagues had no way of knowing what kind of condition the ancient contents would be in, nor did they have any idea of what was inside. The first items removed from the time capsule were folded newspapers. They

were in “amazingly good condition” according to Hatchfield. There were five newspapers all, including copies of the Boston Bee and Boston Traveler. Next they removed 23 coins, in denominations of half-cent (something modern people haven’t heard of), penny, quarter, dime and half-dime (Isn’t that a nickel? I guess it hadn’t been named yet). Some of the coins dated back to the mid-19th century, but some were from 1795. There was also a so-called “Pine Tree Shilling” dated to 1652. Just the coins alone are an amazing find, but they wouldn’t be proof of who had placed them in the box. The box also contained a copper medal with George Washington’s image and the words “General of the American Army,” a seal of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and a title page from the Massachusetts Colony Records. There was no clear indication of who it had belonged to. Finally, Hatchfield removed a silver plate with fingerprints still on it, bearing an inscription dedicating the State House cornerstone on the 20th anniversary of American independence in July 1795. While the silver plate is amazing, to me, the fingerprints are a stellar find.

were in “amazingly good condition” according to Hatchfield. There were five newspapers all, including copies of the Boston Bee and Boston Traveler. Next they removed 23 coins, in denominations of half-cent (something modern people haven’t heard of), penny, quarter, dime and half-dime (Isn’t that a nickel? I guess it hadn’t been named yet). Some of the coins dated back to the mid-19th century, but some were from 1795. There was also a so-called “Pine Tree Shilling” dated to 1652. Just the coins alone are an amazing find, but they wouldn’t be proof of who had placed them in the box. The box also contained a copper medal with George Washington’s image and the words “General of the American Army,” a seal of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and a title page from the Massachusetts Colony Records. There was no clear indication of who it had belonged to. Finally, Hatchfield removed a silver plate with fingerprints still on it, bearing an inscription dedicating the State House cornerstone on the 20th anniversary of American independence in July 1795. While the silver plate is amazing, to me, the fingerprints are a stellar find.

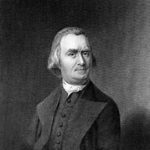

“This cornerstone of a building intended for the use of the legislative and executive branches of the government of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts was laid by his Excellency Samuel Adams, Esquire, governor of the said Commonwealth,” Michael Comeau, executive director of the Massachusetts Archives, read from the plate’s inscription to the assembled crowd, adding “How cool is that.” It is believed that the plate was the work of Paul Revere, the master metalsmith and engraver turned Revolutionary hero who placed the time capsule alongside Adams and William Scollay, a colonel in the Revolutionary War. It took nearly an hour to remove all the items from the time capsule. I’m sure they wanted to be both careful, and also have a really good look at them. The

museum’s conservators then began the work on preserving the contents so they could be put on display. According to the Massachusetts Secretary of State, William Galvin, the time capsule will eventually be returned to the cornerstone, but it’s not certain whether state officials will add any new objects to it before burying it again.

museum’s conservators then began the work on preserving the contents so they could be put on display. According to the Massachusetts Secretary of State, William Galvin, the time capsule will eventually be returned to the cornerstone, but it’s not certain whether state officials will add any new objects to it before burying it again.