History

Most people have attended a circus at one time or another, although they are becoming a little more something from the past. Nevertheless, they used to be huge attractions, and when the circus came to town, almost the whole town turned out to watch the show. That was something that worked against the people of Hartford, Connecticut on July 6, 1944. At that time, Hartford was a city of approximately 13,000 people. The Independence Day festivities had just passed and now the circus was in town to continue the week’s excitement for the townspeople. The Ringling Brothers and Barnum Baily Circus was famous for its incredible show, held under a huge circus tent. At 8,000 people in attendance, about 2/3 of the town was there. It was going to be a great show, and the children of the town were beyond excited.

Most people have attended a circus at one time or another, although they are becoming a little more something from the past. Nevertheless, they used to be huge attractions, and when the circus came to town, almost the whole town turned out to watch the show. That was something that worked against the people of Hartford, Connecticut on July 6, 1944. At that time, Hartford was a city of approximately 13,000 people. The Independence Day festivities had just passed and now the circus was in town to continue the week’s excitement for the townspeople. The Ringling Brothers and Barnum Baily Circus was famous for its incredible show, held under a huge circus tent. At 8,000 people in attendance, about 2/3 of the town was there. It was going to be a great show, and the children of the town were beyond excited.

With the tent filled to capacity, a fire is the worst nightmare, but that is what they had. No one knows exactly what happened, and the 8,000 people inside really had no time in which to react. As panic spread as fact as the fire broke out under the big top of circus, killing 167 people and injuring 682. Two thirds of those who perished  were children. The cause of the fire was unknown, but it spread at incredible speed, racing up the canvas of the circus tent. Suddenly, patches of burning canvas began falling on them from above, and a stampede for the exits began. People became trapped under fallen canvas, but most were able to rip through it and escape, but after the tent’s ropes burned and its poles gave way, the whole burning big top came crashing down, trapping those who remained inside. Within 10 minutes it was over, and some 100 children and 60 of their adult escorts were dead or dying.

were children. The cause of the fire was unknown, but it spread at incredible speed, racing up the canvas of the circus tent. Suddenly, patches of burning canvas began falling on them from above, and a stampede for the exits began. People became trapped under fallen canvas, but most were able to rip through it and escape, but after the tent’s ropes burned and its poles gave way, the whole burning big top came crashing down, trapping those who remained inside. Within 10 minutes it was over, and some 100 children and 60 of their adult escorts were dead or dying.

The fire investigation revealed that the tent had undergone a treatment with flammable paraffin thinned with three parts of gasoline to make it waterproof. These days, no on would consider using gasoline for such a purpose, but unfortunately at that time it was used. Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus eventually agreed to pay $5 million in compensation, and several of the organizers were convicted on manslaughter charges. In 1950, the cause was finally uncovered in the case when Robert D Segee of Circleville, Ohio, confessed to starting the Hartford circus fire. Segee claimed that he had been an arsonist since the age of six and that “an apparition of an Indian on a  flaming horse often visited him and urged him to set fires.” In November 1950, Segee was convicted in Ohio of unrelated arson charges and sentenced to 44 years of prison time. The Hartford investigators raised doubts over his confession. Segee had a history of mental illness, and it could not be proven he was anywhere within the state of Connecticut when the fire occurred. Connecticut officials were also not allowed to question Segee, even though his alleged crime had occurred in their state. Segee, who died in 1997, denied setting the fire as late as 1994 during an interview. Because of this, many investigators, historians, and victims believe the true arsonist…if it was indeed arson…was never found.

flaming horse often visited him and urged him to set fires.” In November 1950, Segee was convicted in Ohio of unrelated arson charges and sentenced to 44 years of prison time. The Hartford investigators raised doubts over his confession. Segee had a history of mental illness, and it could not be proven he was anywhere within the state of Connecticut when the fire occurred. Connecticut officials were also not allowed to question Segee, even though his alleged crime had occurred in their state. Segee, who died in 1997, denied setting the fire as late as 1994 during an interview. Because of this, many investigators, historians, and victims believe the true arsonist…if it was indeed arson…was never found.

For many years, my husband, Bob Schulenberg and I have gone to the Black Hills to celebrate Independence Day. It has been our tradition for about 30 years. This year, things got changed up a bit. Our daughter, Amy Royce and her husband Travis invited us to come to Washington to spend the holiday with them. We will be watching the fireworks display at Semiahmoo Bay on the 4th. Bob and I went there a couple of years ago when we spent Thanksgiving with Amy’s family. The bay is beautiful, and I’m sure it will be even more fun in the summertime warmth…although it wasn’t very cold in November. We have never seen fireworks set off over water, so that will definitely be something new, and something about which we are very excited.

For many years, my husband, Bob Schulenberg and I have gone to the Black Hills to celebrate Independence Day. It has been our tradition for about 30 years. This year, things got changed up a bit. Our daughter, Amy Royce and her husband Travis invited us to come to Washington to spend the holiday with them. We will be watching the fireworks display at Semiahmoo Bay on the 4th. Bob and I went there a couple of years ago when we spent Thanksgiving with Amy’s family. The bay is beautiful, and I’m sure it will be even more fun in the summertime warmth…although it wasn’t very cold in November. We have never seen fireworks set off over water, so that will definitely be something new, and something about which we are very excited.

Celebrating our nation’s independence has always been a favorite holiday for Bob and me. We love everything about it. The fireworks take my thoughts back to history lessons, of the Revolutionary War. The rockets shot at ships, and the fighting that took place because we were a nation ready to be our own country. The fighting was sometimes brutal, but it was necessary. The patriots willingly gave their lives for the cause of independence. The fighting took place on land and water, and yet we have never seen fireworks over the water…until now. In my mind, I can see the ships from the Revolutionary War out in the bay. I can imagine the fireworks are the rockets, and the war is real. Nevertheless, I am glad that it isn’t really real, because I would not want our soldiers to have to relive that, but I can feel like a mouse in the corner, watching as history unfolds in front of my eyes…at least I can imagine it.

Of course, the fireworks aren’t the real thing, but rather just reminder of what our nation and the soldiers who fought for our independence, went through. My imagination of happened is just that…a figment of my imagination, because those events are long in the past. Still, I don’t believe that we should ever forget the lessons of war. There is always a reason we go to war…a wrong that must be made right, tyranny that must be stopped, killing that must be squashed, and slaves who must be made free. Good nations don’t go to war for

evil purposes. I believe that the most important lesson to be taken away from any war, is that we must never trust our enemies, and even more importantly, we must never allow the enemy to infiltrate our nation and our government. Happy Independence Day to our great nation…the United States of America. Forever may our flag fly and forever may our nation stand.

evil purposes. I believe that the most important lesson to be taken away from any war, is that we must never trust our enemies, and even more importantly, we must never allow the enemy to infiltrate our nation and our government. Happy Independence Day to our great nation…the United States of America. Forever may our flag fly and forever may our nation stand.

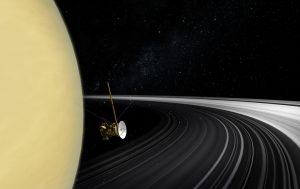

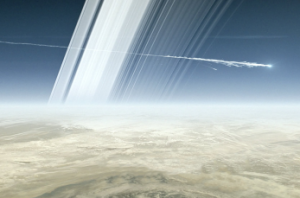

When we think of space exploration, I think most of us think about the moon or the International Space Station, but NASA has really done more exploring of other areas that it has of the moon. One such mission was NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, and the Huygens probe. Cassini launched in 1997, along with ESA’s Huygens probe. It was a joint endeavor of NASA, the European Space Agency, or ESA, and the Italian Space Agency. For six months in 2000, the spacecraft contributed to studies of Jupiter, before continuing on to its destination…Saturn, on June 30, 2004 and starting a string of flybys of Saturn’s moons. The Huygens probe was released later that year on Saturn’s moon Titan to conduct a study of the moon’s atmosphere and surface composition. In its second extended mission, Cassini made the first observations of a complete seasonal period for Saturn and its moons, flew between the rings and descended into the planet’s atmosphere.

When we think of space exploration, I think most of us think about the moon or the International Space Station, but NASA has really done more exploring of other areas that it has of the moon. One such mission was NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, and the Huygens probe. Cassini launched in 1997, along with ESA’s Huygens probe. It was a joint endeavor of NASA, the European Space Agency, or ESA, and the Italian Space Agency. For six months in 2000, the spacecraft contributed to studies of Jupiter, before continuing on to its destination…Saturn, on June 30, 2004 and starting a string of flybys of Saturn’s moons. The Huygens probe was released later that year on Saturn’s moon Titan to conduct a study of the moon’s atmosphere and surface composition. In its second extended mission, Cassini made the first observations of a complete seasonal period for Saturn and its moons, flew between the rings and descended into the planet’s atmosphere.

Upon arrival at Saturn, Cassini-Huygens began its mission by doing several flybys of Saturn’s moons. Saturn has at least 150 moons and moonlets in total, though only 62 have confirmed orbits and only 53 have been given official names. Every year, it seems, more moons are discovered. Most of the moons are small, icy bodies that probably broke off of Saturn’s impressive ring system. In fact, 34 of the moons that have been named are less than 7 miles in diameter while another 14 are 7 to 31 miles in diameter. However, some of its inner and outer moons are among the largest and most dramatic in the Solar System, measuring between 155 and 3106 miles in diameter and housing some of greatest mysteries in the Solar System. These moons aren’t all round, but rather have taken on several unusual and interesting shapes.

The rings of Saturn posed a particular problem if the Cassini was fly through them and descend into Saturn’s atmosphere. The rings of Saturn are the most extensive ring system of any planet in the Solar System. They consist of countless small particles, ranging in size from micrometers to meters, that orbit about Saturn. The ring particles are made almost entirely of water ice, with a trace component of rocky material. No one really

understands exactly how the rings are formed. Although theoretical models indicated that the rings were likely to have formed early in the Solar System’s history, new data from Cassini suggest they formed relatively late. That and several other things about Saturn are the reasons for its exploration. On September 15, 2017, twenty years after the Cassini-Huygens mission began, it was over, and Cassini began its Final Entry into Saturn’s Atmosphere…breaking up as it broke through.

understands exactly how the rings are formed. Although theoretical models indicated that the rings were likely to have formed early in the Solar System’s history, new data from Cassini suggest they formed relatively late. That and several other things about Saturn are the reasons for its exploration. On September 15, 2017, twenty years after the Cassini-Huygens mission began, it was over, and Cassini began its Final Entry into Saturn’s Atmosphere…breaking up as it broke through.

Santa Barbara, California is a picturesque area with mountains to the east, ocean to the west, and palm trees everywhere. It seems like a perfect kind of paradise, and most of the time it probably is, but on June 29, 1925, many things changed. That morning, a magnitude between 6.5 and 6.8 earthquake hit the area of Santa Barbara. Although no foreshocks were reportedly felt before the mainshock, a pressure gauge recording card at the local waterworks showed disturbances beginning at 3:27am, which were likely caused by minor foreshocks. Then, at 6:44am the mainshock occurred, lasting 19 seconds. The earthquake’s epicenter was in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Santa Barbara, in the Santa Barbara Channel. It is thought that the fault on which it occurred is an extension of the Mesa fault or the Santa Ynez system. The earthquake was felt from Paso Robles in San Luis Obispo County to the north to Santa Ana in Orange County to the south and to Mojave in Kern County to the east. Major damage occurred in the city of Santa Barbara and along the coast, as well as north of Santa Ynez Mountains, including Santa Ynez and Santa Maria valleys.

Santa Barbara, California is a picturesque area with mountains to the east, ocean to the west, and palm trees everywhere. It seems like a perfect kind of paradise, and most of the time it probably is, but on June 29, 1925, many things changed. That morning, a magnitude between 6.5 and 6.8 earthquake hit the area of Santa Barbara. Although no foreshocks were reportedly felt before the mainshock, a pressure gauge recording card at the local waterworks showed disturbances beginning at 3:27am, which were likely caused by minor foreshocks. Then, at 6:44am the mainshock occurred, lasting 19 seconds. The earthquake’s epicenter was in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Santa Barbara, in the Santa Barbara Channel. It is thought that the fault on which it occurred is an extension of the Mesa fault or the Santa Ynez system. The earthquake was felt from Paso Robles in San Luis Obispo County to the north to Santa Ana in Orange County to the south and to Mojave in Kern County to the east. Major damage occurred in the city of Santa Barbara and along the coast, as well as north of Santa Ynez Mountains, including Santa Ynez and Santa Maria valleys.

Those were 19 seconds that started a disaster of epic proportions. The earthquake was immediately complicated when the dam broke and water mains burst. The earthen Sheffield Dam had been built near the city in 1917. It was 720 feet long and 25 feet high and held 30 million gallons of water. The soil under the dam liquefied during the earthquake and the dam collapsed. This was the only dam to fail during an earthquake in the United States until the Lower San Fernando Dam failed in 1971. When it burst, a wall of water swept between Voluntario and Alisos Streets destroying trees, cars, three houses and flooding the lower part of town to a depth of 2 feet. The rushing water caused some areas of the city to be flattened. People as far away as San Francisco and Los Angeles felt the earthquake, reporting millions of dollars worth of damage across California. The earthquake was even felt in other states as far away as Montana, who reported more damage. The earthquake destroyed the historic center of the city, with damage estimated at $8 million in 1925, or about $117 million today.

Thirteen people lost their lives that day, but it may have been far worse without the actions of three heroes. Those heroes shut off the town gas and electricity preventing a catastrophic fire. Most homes survived the earthquake in relatively good condition, with the exception of the fact that every chimney in the city crumbled. The downtown area of Santa Barbara was in complete ruins. On State Street, the main commercial street, only a few buildings remained standing after the earthquake. The City Cab building, The Californian, and Arlington garages…all large and fully occupied parking structures…collapsed. They were full of cars. Many other vehicles were crushed in the downtown area too. At least one death was the result of the San Marcos building crushing a car, as walls of buildings fell onto cars parked there. In the 36 block business district, only a few structures were not substantially damaged. Many had to be completely demolished and rebuilt. The façade of the church of the Mission Santa Barbara was severely damaged and lost its statues. Many important buildings, including hotels, offices, and the Potter Theater, were lost. The courthouse, jail, library, schools, and churches were among the buildings sustaining serious damage. Concrete curbs buckled in almost every block in Santa Barbara. Pavement on the boulevard along the beach was displaced by about a foot to a foot and a half, but oddly, the pavement in the downtown area was virtually not damaged.

Railroad tracks were damaged in several places between Ventura and Gaviota. In particular, a portion between Naples and Santa Barbara was badly damaged. Seaside bluffs fell into the ocean, and a slight tsunami was felt by offshore ships. The town was completely cut off from telephone and telegraph, and the only source of news was from shortwave radios. Because the gas was shut off, there was an absence of post-earthquake fires. This allowed scientists to study earthquake damage to various types of construction. That was a rare things for the scientists. The American Legion and the Naval Reserves from the Naval Reserve Center Santa Barbara patrolled the streets looking to inhibit looters of the damaged businesses and homes. Additional fire and police personnel arrived from as far as Los Angeles to assist the sailors and soldiers in maintaining order. Three strong aftershocks occurred at 8:00am, 10:45am, and 10:57am, but without further damage. There were many smaller shocks that continued throughout the day. An aftershock on July 3 caused additional cracked walls and damaged chimneys. Since downtown Santa Barbara suffered so much damage, there was a large-scale construction effort in 1925 and 1926 aimed at removing or repairing damaged structures and constructing new buildings. This new construction completely altered the character of the city center. Before the earthquake, a considerable part of the center was built in the Moorish Revival style. After the earthquake, the decision was made to rebuild it in the Spanish Colonial Revival style. This effort was undertaken by the Santa Barbara Community Arts Association, which was founded in the beginning of the 1920s and viewed the earthquake as the opportunity to rebuild the city center in the unified architectural style. As a result, many buildings later

listed on National Register of Historic Places were designed in the late 1920s, among them the Santa Barbara County Courthouse and the front of the Andalucia Building. Building codes in Santa Barbara were also made more stringent after the earthquake demonstrated that traditional construction techniques of unreinforced concrete, brick, and masonry were unsafe and unlikely to survive strong quakes.

listed on National Register of Historic Places were designed in the late 1920s, among them the Santa Barbara County Courthouse and the front of the Andalucia Building. Building codes in Santa Barbara were also made more stringent after the earthquake demonstrated that traditional construction techniques of unreinforced concrete, brick, and masonry were unsafe and unlikely to survive strong quakes.

In any war, when soldiers are killed or wounded in battle, their guns, grenades, and bullets were left behind…forgotten. Those who assisted the wounded and carried off the dead, had more important things to attend to than the soldier’s weapons and such, which were simply left behind…discarded. As the front lines shifted from one area to another, battlefields were deserted, and in the absence of the trampling footsteps of the soldiers, the grass and low plants began to grow again. As the months and years passed, trees continued to grow. The littered items somehow became embedded in the bark of the growing trees. That phenomena has always amazed me. How could the tree bark accept this odd foreign object into itself…and yet it did. Of course, it was not without scars that the odd pair would coexist. The foreign items would be wrapped with a knotted looking bulge, or would appear to eat up portions of the foreign object, while completely ignoring another part, as if it was simply laying beside it.

In any war, when soldiers are killed or wounded in battle, their guns, grenades, and bullets were left behind…forgotten. Those who assisted the wounded and carried off the dead, had more important things to attend to than the soldier’s weapons and such, which were simply left behind…discarded. As the front lines shifted from one area to another, battlefields were deserted, and in the absence of the trampling footsteps of the soldiers, the grass and low plants began to grow again. As the months and years passed, trees continued to grow. The littered items somehow became embedded in the bark of the growing trees. That phenomena has always amazed me. How could the tree bark accept this odd foreign object into itself…and yet it did. Of course, it was not without scars that the odd pair would coexist. The foreign items would be wrapped with a knotted looking bulge, or would appear to eat up portions of the foreign object, while completely ignoring another part, as if it was simply laying beside it.

Like the weapons of war, the soldiers’ helmets were often discarded in an injury or more likely death situation. The likelihood of survival for the owner of a helmet that contained a bullet hole, was slim to none. The helmet was not likely to be needed by its owner again, so the helmet lay on the battlefield where it had been discarded. As time went on, the little sapling trees growing up after the end of the war started up under the helmet. In order for the tree to grow up, it had to make its way, somehow through the helmet or to topple it in order to survive. A bullet hole provided the perfect way to get through the heavy helmet. The tiny tree peeked through the hole to find the sunlight necessary for the tree’s survival. As the tree grew, the corroding helmet allowed the hole to be expanded, and the tree became larger. Soon the helmet became a part of the growing tree. There was not a knotted wrapping of the tree around the helmet, but rather the helmet took on a mushroom like appearance. It looked like an odd sort of umbrella to anyone who might come across this odd marriage of nature and the man-made helmet. Only on occasion did the tree protest the marriage, or the helmet refuse to allow the expansion of the hole, thereby creating the knot that was so often seen as the tree

absorbed the foreign object. Even then, the tree could not fully absorb the helmet, and so it looked almost like the tree was wearing the helmet on its knotted head…and the branches protruding from the knot looked like messy hair. The strange looking trees, were a lingering reminder of a war that was long over, but somehow not forgotten…and nature prevails.

absorbed the foreign object. Even then, the tree could not fully absorb the helmet, and so it looked almost like the tree was wearing the helmet on its knotted head…and the branches protruding from the knot looked like messy hair. The strange looking trees, were a lingering reminder of a war that was long over, but somehow not forgotten…and nature prevails.

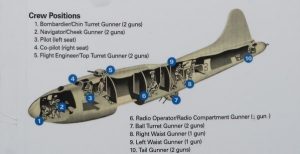

B-17 crews were a tight group. Mostly these crews flew with the same crew on missions, but sometimes, someone was sick, went home, or was killed, and crews changed. For that reason, it was vital that everyone know their responsibilities. We shouldn’t write about the B-17 as a bomber without writing about the crew. In reality, the crew and their Fortress worked much like one unit. I think the crew came to love the fortress that kept them safe.

B-17 crews were a tight group. Mostly these crews flew with the same crew on missions, but sometimes, someone was sick, went home, or was killed, and crews changed. For that reason, it was vital that everyone know their responsibilities. We shouldn’t write about the B-17 as a bomber without writing about the crew. In reality, the crew and their Fortress worked much like one unit. I think the crew came to love the fortress that kept them safe.

In the cockpit, you would find the standard, pilot and co-pilot. The pilot was the commander of the crew. He was in command of the B-17, but he was also responsible for all aspects of crew training, discipline, safety and efficiency at all times, but he was more than the commander, he was also one of the crew, he wasn’t a gunner, but it was his job to bring these men home. The co-pilot was the executive officer. He must be as familiar as the pilot with all aspects of flying the B-17, ready to take over both as pilot and commander, if necessary. The B-17 required a flight crew of two to fly the plane, much like modern day jets. The co-pilot operated the instruments on the right and instruments on the left were run by the pilot. Nevertheless, in an emergency, one could fly the plane.

The navigator had the job of making sure that the plane made it to the target, and back home again. He used one or more ways of navigating: dead reckoning; using charts and visual references; pilotage, using charts along with time, distance, and speed calculations; use of radio navigation aides; and using the sun observations or at night using stars and planets. As the B-17 gets close to the target, the bombardier takes over command of the plane (including flying) as they approached the bomb target. Then, when they arrived at the target he released the bombs. Accurate bombing was crucial and that was the bombardier’s responsibility. If he wasn’t accurate, they could hit a school, a neighborhood, or other civilian area. Later on in WW II, the navigator and bombardier positions were combined into one position done by one man.

The radio operator’s job was communications, working the radios, and keeping the radios in good working order. There was a lot of radio equipment in the B-17 that allowed for both communications and navigation. He maintained a log and was often the photographer of the crew. A good radio operator knew his equipment inside out. But the radio operator was also a trained gunner. The flight engineer was one of the most important people on the plane. He knew all the equipment on the B-17 better than the pilot or any other crew member from the engines to the radio equipment to the armament to the engines to the electrical system and everything else. Many flight engineers served as maintenance crew chiefs before moving to the position of a B-17 flight engineer. The flight engineer was the final person to advise the pilot of the airworthiness of the plane before each mission. A wise pilot listened. The flight engineer doubles as top turret gunner.

A typical crew had four gunners, sometimes less. In a configuration of four gunners there were two waist gunners (right and left), a tail gunner, and a ball turret gunner. The two waist gunners station was in the middle of the plane. As the name implies, the tail gunner’s position was in the tail and the ball turret gunner (a small man) position was in a turret underneath the B-17. Each gunner was responsible for their own armament and ensuring that their guns were in working order. Their whole job was to keep the enemy planes and enemy fire off of the B-17. So close was the relationship that these 10 men shared, that many would go on to remain friends for life, and even name their children after their respected crew mates.

A typical crew had four gunners, sometimes less. In a configuration of four gunners there were two waist gunners (right and left), a tail gunner, and a ball turret gunner. The two waist gunners station was in the middle of the plane. As the name implies, the tail gunner’s position was in the tail and the ball turret gunner (a small man) position was in a turret underneath the B-17. Each gunner was responsible for their own armament and ensuring that their guns were in working order. Their whole job was to keep the enemy planes and enemy fire off of the B-17. So close was the relationship that these 10 men shared, that many would go on to remain friends for life, and even name their children after their respected crew mates.

The pilots of the war birds were brave men. They were tasked with staying the course while under heavy anti-aircraft fire and flak. That would be a major undertaking for most of us because in that situation, all our mind can think to do is to turn and run. These men had to stay in place so they could make the bomb runs, or protect those who were. Of course, there were gunners tasked with keeping the enemy planes at bay, but they couldn’t fly the plane to get you home.

The pilots of the war birds were brave men. They were tasked with staying the course while under heavy anti-aircraft fire and flak. That would be a major undertaking for most of us because in that situation, all our mind can think to do is to turn and run. These men had to stay in place so they could make the bomb runs, or protect those who were. Of course, there were gunners tasked with keeping the enemy planes at bay, but they couldn’t fly the plane to get you home.

United States Army Air Force Lieutenant William R Lawley Jr, was a pilot on a B-17 Bomber on February 20, 1944. It was the first day of “Big Week,” and Lieutenant Lawley’s Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress was at the head of a formation of one thousand bombers sent to bomb Germany’s production and aircraft manufacturing facilities. “Big Week” was the Allied plan to spend seven days ruthlessly dropping explosives onto enemy aircraft production facilities deep behind enemy lines. Day and night, wave after wave of American B-17 Flying Fortresses, B-24 Liberators, and British Lancasters blasted shipyards, railroad junctions, power plants, airfields, steel production facilities, dams, and military bases relentlessly, igniting everything from ball bearing plants to oil refineries up into towering explosive fireballs, to make it impossible for anyone in Germany to build a working fighter plane.

Suddenly, the call rang out, “Bandits, incoming, three o’clock high!” Immediately, the gunners began shooting to fight off the enemy planes, while Lawley held the plane steady. The loud, rumbling propellers roared as he pushed open the throttle and smashed through a thick black cloud of anti-aircraft smoke at nearly three hundred miles an hour, all while keeping in tight formation with hundreds of other B-17s. A pair of Nazi Focke-Wulf 190 fighter planes screamed by, ripping off thousands of rounds from twin-linked machine guns and heavy 20mm autocannons. Black puffs of enemy artillery popped up all around Lawley’s massive aircraft craft. The enemy fighters screamed past at speeds of over four hundred miles an hour. As the gray Nazi fighters dove down towards another squadron of American bombers below, Lawley’s starboard waist gunner zeroed in on them with his .50-caliber machine gun with a quick burst of tracer fire, but had to release the trigger as a pair of American P-47 Thunderbolt fighter planes dropped in to chase them. These Bomber raids were nothing new for Lawley. Born in Alabama, this 23 year old veteran pilot had already flown nine missions over Germany in the last year. This was his tenth mission, but the first at the controls of a brand-new B-17, nicknamed Cabin in the Sky III, because the first two Cabin in the Sky aircraft been blown up.

Suddenly, voices on the intercom called out enemy fighters, this time diving down from behind. With the sun at their backs, blinding the tail gunner, the Focke-Wulfs ignored the deadly clouds of flak ripping apart the sky around them and hurtled straight into the B-17 formation. Their 20mm cannons struck home at one of Lawley’s wingmen, catching her engines on fire and dropping her out of the sky like a brick. Another flak explosion hit even closer, rocking Cabin in the Sky III and peppering one of the engines with shards of metal, causing it to burst into flames. Lawley ordered the copilot to shut it down and kept moving. More calls came in. “Six o’clock low.” “Three o’clock level.” The Nazis were everywhere, attacking from seemingly every direction at once. The B-17s stuck close together, knowing that the only way to survive was to stay close and lay down heavy fields of  machine gun fire. As his gunners fired in every direction, Lawley looked through his cockpit window to see a fleet of twenty or so 190s drop down in front of him, pick out targets, and open fire. With a deafening crash, a 20mm high explosive autocannon shell bust through the front window of the pane, exploding in the cockpit. Everything went black.

machine gun fire. As his gunners fired in every direction, Lawley looked through his cockpit window to see a fleet of twenty or so 190s drop down in front of him, pick out targets, and open fire. With a deafening crash, a 20mm high explosive autocannon shell bust through the front window of the pane, exploding in the cockpit. Everything went black.

Lawley snapped awake seconds later, his ears ringing. Alarms were going off all across his console, which was now riddled with shards of shrapnel. His right arm was shattered. Through blurry vision, Lawley saw his co-pilot slumped over dead, his body laying on the control stick pushing it forward, putting the plane was in a steep dive. The loaded bomb racks made matters worse. The pilot-side window was smashed, and broken glass had gone into Lawley’s face, arms, and side. The windshield was so smeared with blood and oil that he could barely see out of it. Another engine was one fire. Lieutenant William Lawley didn’t panic. He did his job. Determined to keep his plane and his crew alive, the veteran USAAF pilot reached out with his shattered right arm, grabbed his dead co-pilot, and somehow pulled him back off the controls. Then, with just his left hand, he manually fought a 15-ton bomber aircraft out of a ninety-degree nosedive at 12,000 feet, leveled it off, and shut down the second burning engine. Looking up, he saw the Focke-Wulf pilots circling around for another pass, so this grim warrior made an evasive turn, dove the plane down into the cloud cover, and accelerated out of there as fast as he could. Other B-17s in the formation had radioed Cabin in the Sky III as Killed in Action, but somehow William Lawley managed to evade the enemy fighters and get the heck out of Leipzig. He flew across Germany, dodging enemy AA positions, then flew in low over the French countryside and ordered the surviving eight members of his crew to grab parachutes and bail out. It was then that he learned all eight crewmen were wounded in the attack, and that two of them were hurt so bad they couldn’t possibly go skydiving right now. Lawley said, “Ok. I’m going to get us home then.” Nobody jumped out of the plane.

The bombardier eventually got the racks unstuck and released his bombs over an unimportant part of the French countryside, but before long another squadron of Me-109 fighters picked up the wounded B-17 on radar and came swooping in for the kill. With his guys running to their guns to bark .50-caliber machine gun fire, Lawley hammered the stick of his crippled plane, dodging and evading with one arm and somehow eluding enemy fighters one more time. In the process, however, he had to use more fuel than he’d have liked, and one of the two remaining engines was now almost completely out of gas. Once the coast was clear and the Messerschmitt fighter planes were gone, Lawley leveled off the plane and promptly passed out from loss of blood. This was the days before autopilot, and Lawley was the only guy who knew how to fly the plane. Luckily his navigator figured out what was up and woke him up pretty much right away.

Cabin in the Sky III somehow reached the English Channel against all odds, received emergency landing permission from a Canadian fighter base on the English coast and, just in case you’re wondering how the heck this could possibly get any worse, when William Lawley hit the button to drop his landing gear, it didn’t deploy. So, limping in with three burned-out engines, “feathering” his only working one by pumping it off and on with small amounts of gas, half blinded by broken glass, exhausted from loss of blood, and with no landing gear, eight wounded crew members, and one good arm, Lieutenant William Lawley attempted to crash land a 15-ton B-17 on a grass airfield about the size of a soccer pitch. He came in hard on his belly, sliding across the airfield, finally coming to a rest just outside the Canadian barracks. Every member of his crew survived. Lawley walked out of the wreckage, spend a few weeks in the hospital, and make a full recovery. He successfully piloted four more bombing missions before the war was over. Did he earn his Modal of Honor? Without a doubt!!

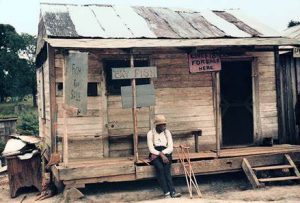

When the Great Depression hit, people in the upper-middle class, like doctors, lawyers, and other professionals, saw their incomes drop by 40%, but the middle class and low income Americans found themselves with nothing. They had no jobs and no money, and even if they did have those things, they couldn’t afford the things they needed. The prices for everything from food to clothing were much more than their meager income could buy much of. People began to move from place to place looking for a job…any job. The problem was that there were very few jobs, and lot of people standing in line to get them. The average American lived by the Depression-era motto: Use it up, wear it out, make do, or do without. People had to learn to be frugal. Clothes were patched when the started to wear out. People planted gardens and even kept little gardens in their kitchen. They stayed home, instead of evenings out. They were always in a private struggle to keep their cars or homes.

When the Great Depression hit, people in the upper-middle class, like doctors, lawyers, and other professionals, saw their incomes drop by 40%, but the middle class and low income Americans found themselves with nothing. They had no jobs and no money, and even if they did have those things, they couldn’t afford the things they needed. The prices for everything from food to clothing were much more than their meager income could buy much of. People began to move from place to place looking for a job…any job. The problem was that there were very few jobs, and lot of people standing in line to get them. The average American lived by the Depression-era motto: Use it up, wear it out, make do, or do without. People had to learn to be frugal. Clothes were patched when the started to wear out. People planted gardens and even kept little gardens in their kitchen. They stayed home, instead of evenings out. They were always in a private struggle to keep their cars or homes.

Paint was too expensive, so home fell into disrepair. As things got worse, things began to wear out, and people didn’t get rid of the junk. They simply put it out in the yard. I’m sure that they realized that every piece of junk had parts in it that could be used for repairs to something else. Everything could be reworked. They used the  backs of worn-out overall legs to make pants for little boys and overalls for babies. They didn’t have disposable diapers back then. They made diapers and underwear out of flour and sugar sacks. When the older kids outgrew their clothes, but they were too big for the younger kids, they made smaller clothes out of bigger hand-me-downs. If their shoes wore out before a year, the children went barefooted. Many people resorted to bartering…not only goods for goods, but work for work. They tried to make their homes and their lives pretty, even in depressing times. They used patterned chicken feed sacks to make curtains, aprons, and little girl’s dresses. Worn out socks were kept, so that they could patch another sock. Nothing was thrown away. They saved string that came loose from clothing and added it to a string ball for mending and sewing. Toilet paper was a luxury that many people couldn’t afford, so they used newspaper instead. They saved every scrap of material for making quilts. People learned not to waste anything.

backs of worn-out overall legs to make pants for little boys and overalls for babies. They didn’t have disposable diapers back then. They made diapers and underwear out of flour and sugar sacks. When the older kids outgrew their clothes, but they were too big for the younger kids, they made smaller clothes out of bigger hand-me-downs. If their shoes wore out before a year, the children went barefooted. Many people resorted to bartering…not only goods for goods, but work for work. They tried to make their homes and their lives pretty, even in depressing times. They used patterned chicken feed sacks to make curtains, aprons, and little girl’s dresses. Worn out socks were kept, so that they could patch another sock. Nothing was thrown away. They saved string that came loose from clothing and added it to a string ball for mending and sewing. Toilet paper was a luxury that many people couldn’t afford, so they used newspaper instead. They saved every scrap of material for making quilts. People learned not to waste anything.

Every part of the food was used. Potato peels were food, not waste. They made soup out of a few vegetables and a scrap of meat…for flavor only. They hunted for rabbits and fished to put what protein they could on the table. When there was nothing more to eat, they had lard sandwiches. I seriously doubt if many people went to  bed with a full stomach, but that didn’t mean that you turned away a stranger who was hungry. These people knew hw bad things were for them, and so they helped their neighbors. Nevertheless, during the Great Depression, suicide rates in the United States reached an all-time high, topping 22 suicides per 100,000 people. The living conditions were deplorable, and many people couldn’t take it. They felt that somehow they were at fault. still, for the majority of Americans, that didn’t mean that they gave up. Neighbor looked out for neighbor, and families came together to support each other, and while the effects of the Great Depression lasted for 12 years, this too passed, and the nation healed again.

bed with a full stomach, but that didn’t mean that you turned away a stranger who was hungry. These people knew hw bad things were for them, and so they helped their neighbors. Nevertheless, during the Great Depression, suicide rates in the United States reached an all-time high, topping 22 suicides per 100,000 people. The living conditions were deplorable, and many people couldn’t take it. They felt that somehow they were at fault. still, for the majority of Americans, that didn’t mean that they gave up. Neighbor looked out for neighbor, and families came together to support each other, and while the effects of the Great Depression lasted for 12 years, this too passed, and the nation healed again.

On January 17, 1920, the law prohibiting the use or sale of alcohol in the United States went into effect. Before long, illegal bars, called speakeasies were trying to pass off dangerous locally made industrial alcohol as the real thing, but customers were quickly rejecting the foul-tasting brew. The people were demanding quality, authentic Scotch and other liquor “right off the boat.” Within weeks, organized smuggling of imported whiskey, rum, and other liquor, called Rumrunning began. Among the customers for imported booze from Europe, Canada and the Caribbean were the nation’s bootleggers who ran and supplied thousands of speakeasies. Tops among them were Big Bill Dwyer (dubbed “King of the Bootleggers” by the press) and Mob bosses Charles “Lucky” Luciano in New York and Al Capone in Chicago.

On January 17, 1920, the law prohibiting the use or sale of alcohol in the United States went into effect. Before long, illegal bars, called speakeasies were trying to pass off dangerous locally made industrial alcohol as the real thing, but customers were quickly rejecting the foul-tasting brew. The people were demanding quality, authentic Scotch and other liquor “right off the boat.” Within weeks, organized smuggling of imported whiskey, rum, and other liquor, called Rumrunning began. Among the customers for imported booze from Europe, Canada and the Caribbean were the nation’s bootleggers who ran and supplied thousands of speakeasies. Tops among them were Big Bill Dwyer (dubbed “King of the Bootleggers” by the press) and Mob bosses Charles “Lucky” Luciano in New York and Al Capone in Chicago.

Liquor was smuggled in from any country where it was still legal, and the Rumrunners would then have to find new and unique ways to get it to their buyers. Shipments of whiskey from Great Britain traveled to Nassau in the Bahamas and elsewhere in the Caribbean, before being smuggled to America’s East Coast and New Orleans. Whiskey distilled in Canada was smuggled by ship or across land to the West Coast from British Columbia, to the Midwest from Saskatchewan and Ontario, and to the East from Nova Scotia and the French island of Saint Pierre, a liquor smuggler’s hotspot off Newfoundland. Loads of rum from the Caribbean, imported champagne, and other alcohol also made it ashore. Captains of boats loaded with liquor bottles in false bottoms beneath fish bins anchored offshore at designated areas waiting for “contact boats,” small high-speed crafts with buyers who tossed aboard a bundle of large bills bound by elastic bands,  loaded their liquor orders onto their boats and sped to shore to load it onto trucks headed for New York, Boston and other cities. One such stretch of ocean for liquor-selling boats, famously called “Rum Row,” ran from New York to Atlantic City, 12 miles out in international waters to avoid the U.S. Coast Guard.

loaded their liquor orders onto their boats and sped to shore to load it onto trucks headed for New York, Boston and other cities. One such stretch of ocean for liquor-selling boats, famously called “Rum Row,” ran from New York to Atlantic City, 12 miles out in international waters to avoid the U.S. Coast Guard.

The “golden years” of rumrunning were the early 1920s…before Bureau of Prohibition agents, local police and the Coast Guard knew just what liquor smugglers were up to. On the Detroit River, Detroit’s vicious Purple Gang used speed boats to run liquor into town from Windsor, Ontario. They also hijacked the loads their competitors. One infamous Western rumrunner was Roy Olmstead, who shipped Canadian whiskey from a distillery in Victoria in southwestern Canada down the Haro Strait, stashing it on D’Arcy Island on its way to Seattle. Olmstead was making $200,000 a month before Prohibition agents tapped his phone, leading to his arrest and end as a rumrunner in 1924. Individual bootleggers transporting booze by land to Seattle would hide it in automobiles under false floorboards with felt padding or in fake gas tanks. Sometimes whiskey was mixed with the air in the tubes of tires. To fool authorities at the border, a smuggler might have a woman and child inside his car with hidden liquor or even stow it inside a school bus transporting children. Out at sea or on the Great Lakes, rumrunners in schooners or motor boats contended with the Coast Guard, rough weather and frozen water. Even worse were the “go-through guys,” hoodlums armed with pistols and machines guns in speed boats who hijacked the ships, stole cargo, cash, and at times killed rumrunners’ crews and sank their ships.

The fast-moving rumrunners frustrated the Coast Guard so much by 1923 that Commandant William E.  Reynolds asked the federal government for 200 more cruisers and 90 speed boats for patrols to catch up with the contact boats. The agency also added 36 World War I naval ships to enforce Prohibition and employ 11,000 officers and crew. On June 20, 1923, a large fleet of Seaplanes were to be mobilized in an attempt to catch rum smugglers off the Atlantic Coast, it was believed these would be more successful than current means of catching the rum runners who are equipped with very fast boats that are outrunning federal agents. The reality is that they never really stopped the smuggling of liquor into the United States, and in the end, prohibition proved to be a miserable failure. On December 5th, 1933, when the 21st Amendment was ratified, Prohibition was abolished in the United States.

Reynolds asked the federal government for 200 more cruisers and 90 speed boats for patrols to catch up with the contact boats. The agency also added 36 World War I naval ships to enforce Prohibition and employ 11,000 officers and crew. On June 20, 1923, a large fleet of Seaplanes were to be mobilized in an attempt to catch rum smugglers off the Atlantic Coast, it was believed these would be more successful than current means of catching the rum runners who are equipped with very fast boats that are outrunning federal agents. The reality is that they never really stopped the smuggling of liquor into the United States, and in the end, prohibition proved to be a miserable failure. On December 5th, 1933, when the 21st Amendment was ratified, Prohibition was abolished in the United States.