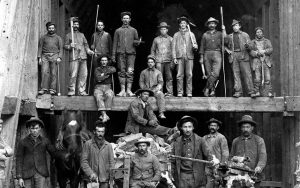

It is in times of greatest need, that people seem to best show that they can pull together to accomplish the greatest tasks. During World War I, the city of Butte, Montana was already a unionized industrial city with a population of 91,000 people. The city was home to one of the largest mining operations in the world. Butte was home to a copper mine system consisting of the Granite Mountain and Speculator Mines, and because of the heightened need for copper at that time, the abundance of employment opportunities drew workers from every corner of the world. The influx of people from other corners meant that more than 30 languages were spoken among the city streets. “No Smoking” signs posted in the mines were printed in 16 different languages, so that there was no mistaking the dangers.

It is in times of greatest need, that people seem to best show that they can pull together to accomplish the greatest tasks. During World War I, the city of Butte, Montana was already a unionized industrial city with a population of 91,000 people. The city was home to one of the largest mining operations in the world. Butte was home to a copper mine system consisting of the Granite Mountain and Speculator Mines, and because of the heightened need for copper at that time, the abundance of employment opportunities drew workers from every corner of the world. The influx of people from other corners meant that more than 30 languages were spoken among the city streets. “No Smoking” signs posted in the mines were printed in 16 different languages, so that there was no mistaking the dangers.

In April of 1917, the United States’ involvement in World War I was in its fourth month, and Butte mines increased their production of copper by operating around the clock, working the 14,500 miners like mules in order to meet the ever increasing demand. Unfortunately, this also brought steadily deteriorating safety conditions. Many of the miners were sleeping in shifts, so the beds in the boarding houses often never went cold. Despite these demanding work conditions, Butte miners worked with a pride and determination seldom found above ground, let alone a half-mile below the surface of the earth. They felt the weight of their duty to the war effort, and they gladly performed their jobs to the best of their abilities. Each day, the men were lowered into the mine, and the previous crew was brought out.

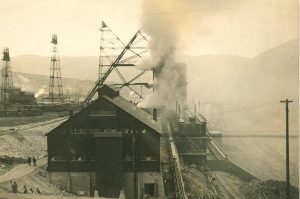

On the evening of June 8, 1917, 410 men were lowered into the Granite Mountain shaft to begin another backbreaking night shift. The exiting day shift had been tasked with the process of lowering a three-ton electric  cable down the shaft to complete work on a sprinkler system designed to protect the mine against fire. All seemed to be going well, but at 8:00 pm the cable slipped from its clamps. As it fell into a tangled coil below the 2400 foot level of the mine, the lead covering was torn away. The torn covering exposed a large portion of oiled paraffin paper, which was used to insulate the cable. Unfortunately, the oiled paraffin paper was also highly flammable. At 11:30 pm four men went down to examine the cable. One of the men accidentally touched his handheld carbide lamp to the oiled paraffin insulation, which immediately ignited. The flame spread quickly to the shaft timbers. The Granite Mountain and Speculator shafts immediately filled with thick, toxic smoke.

cable down the shaft to complete work on a sprinkler system designed to protect the mine against fire. All seemed to be going well, but at 8:00 pm the cable slipped from its clamps. As it fell into a tangled coil below the 2400 foot level of the mine, the lead covering was torn away. The torn covering exposed a large portion of oiled paraffin paper, which was used to insulate the cable. Unfortunately, the oiled paraffin paper was also highly flammable. At 11:30 pm four men went down to examine the cable. One of the men accidentally touched his handheld carbide lamp to the oiled paraffin insulation, which immediately ignited. The flame spread quickly to the shaft timbers. The Granite Mountain and Speculator shafts immediately filled with thick, toxic smoke.

There was a mad scramble to find a way of escape. Just over half of the men working in the Granite Mountain shaft were able to find an escape to the surface. One group of 29 men built a bulkhead to isolate themselves from the smoke and gas. They stayed there for 38 hours before making their way to safety. At the 2254 foot level, another group of 8 men were found behind a makeshift bulkhead over 50 hours from the start of the fire. Two of these men died shortly before their rescue, but the other six were recovered safely. Though the intensity of the fire cannot be disputed, only two men were actually burned to death in a rescue attempt at the onset of the blaze. The rest were simply trapped and overcome by the noxious, suffocating fumes. By the close of the rescue operation on June 16, 1917, eight days after the fire had begun, the death toll had reached its final tally of 168 men.

The Granite Mountain and Speculator Mine Fire was the worst disaster in metal mining history. And we could leave it at that, but then we would be overlooking a remarkable accomplishment…the rescue mission. Over the  course of just 7 days, rescue crews succeeded in searching over 30 miles of drifts and crosscuts, and at least 15 miles of stopes, raises, and manways. Townspeople turned out in droves to help in whatever way the could. All this was done in mine shafts saturated with carbon monoxide and dense, tar-laden smoke. In all, 155 bodies were recovered and removed, all without the loss of a single rescue worker. Despite the tremendous damage the fire caused to the Granite Mountain Mine, it did not stop the work being done there. Copper ore continued to be mined until the mine’s close in 1923. The Butte mines produced the copper that helped electrify America and win World War I. Through this horrible tragedy, Butte received a very special moniker. The city was being called “The Richest Hill on Earth, referencing the soul and determination of the community, rather than the value of the ore beneath its feet.”

course of just 7 days, rescue crews succeeded in searching over 30 miles of drifts and crosscuts, and at least 15 miles of stopes, raises, and manways. Townspeople turned out in droves to help in whatever way the could. All this was done in mine shafts saturated with carbon monoxide and dense, tar-laden smoke. In all, 155 bodies were recovered and removed, all without the loss of a single rescue worker. Despite the tremendous damage the fire caused to the Granite Mountain Mine, it did not stop the work being done there. Copper ore continued to be mined until the mine’s close in 1923. The Butte mines produced the copper that helped electrify America and win World War I. Through this horrible tragedy, Butte received a very special moniker. The city was being called “The Richest Hill on Earth, referencing the soul and determination of the community, rather than the value of the ore beneath its feet.”

One Response to The Richest Hill On Earth