My great grandparents, Carl and Henriette (Hensel) Schumacher immigrated to the United States from Germany, in 1884 and 1882 respectively. It was an amazing time for them. The United States was a whole new world, and for those who came, the land of opportunity. By 1886, they were married and ready to start a family. My grandmother, Anna Schumacher was born in 1887, followed by siblings Albert, Mary (who died before she was 3), Mina, Fred, Bertha, and Elsa, who was born in 1902.

My great grandparents, Carl and Henriette (Hensel) Schumacher immigrated to the United States from Germany, in 1884 and 1882 respectively. It was an amazing time for them. The United States was a whole new world, and for those who came, the land of opportunity. By 1886, they were married and ready to start a family. My grandmother, Anna Schumacher was born in 1887, followed by siblings Albert, Mary (who died before she was 3), Mina, Fred, Bertha, and Elsa, who was born in 1902.

By 1914, World War I broke out, following the assassination of Franz Ferdinand. The government of the United States was understandably nervous about the German immigrants now living in in America. It didn’t matter that many of these people had been living in the united States for a long time, and some had become citizens, married, and had families. The government was still nervous, and I can understand how that could be, because we have the same problem these days with the Muslim nations. Still, when I think about the fact that these were my sweet, kind, and loving, totally Lutheran great grandparents, I find it hard to believe that anyone could be nervous about them. Apparently, I was right, because to my knowledge, they were never detained in any of the internment camps, nor were they even threatened with it.

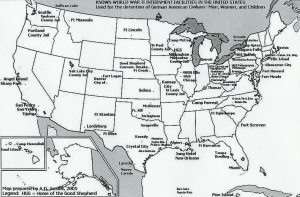

Nevertheless, there were German nationals, and even naturalized citizens who faced possible detention during  World War I and World War II. By World War II, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared Presidential Proclamation 2526, the legal basis for internment under the authority of the Alien and Sedition Acts. With the United States’ entry into World War I, the German nationals were automatically classified as “enemy aliens.” Two of the four main World War I-era internment camps were located in Hot Springs, North Carolina and Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer wrote that “All aliens interned by the government are regarded as enemies, and their property is treated accordingly.”

World War I and World War II. By World War II, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared Presidential Proclamation 2526, the legal basis for internment under the authority of the Alien and Sedition Acts. With the United States’ entry into World War I, the German nationals were automatically classified as “enemy aliens.” Two of the four main World War I-era internment camps were located in Hot Springs, North Carolina and Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer wrote that “All aliens interned by the government are regarded as enemies, and their property is treated accordingly.”

By the time of World War II, the United States had a large population of ethnic Germans. Among residents of the United States in 1940, more than 1.2 million persons had been born in Germany, 5 million had two native-German parents, and 6 million had one native-German parent. Many more had distant German ancestry. With that many people of German ancestry, it seems impossible that they could have detained all of them. Nevertheless, at least 11,000 ethnic Germans, overwhelmingly German nationals were detained during World War II in the United States. The government examined the cases of German nationals individually, and detained relatively few in internment camps run by the Department of Justice, as per its responsibilities under the Alien and Sedition Acts. To a much lesser extent, some ethnic German United States citizens were classified as suspect after due process and also detained. There were also a small proportion of Italian nationals  and Italian Americans who were interned in relation to their total population in the United States. The United States had allowed immigrants from both Germany and Italy to become naturalized citizens, which many had done by then. It was much less likely for those people to be detained, if they had already become citizens. In the early 21st century, Congress considered legislation to study treatment of European Americans during World War II, but it did not pass the House of Representatives. Activists and historians have identified certain injustices against these groups. I suppose that some injustices were done, but those were times of war and strong measures were needed.

and Italian Americans who were interned in relation to their total population in the United States. The United States had allowed immigrants from both Germany and Italy to become naturalized citizens, which many had done by then. It was much less likely for those people to be detained, if they had already become citizens. In the early 21st century, Congress considered legislation to study treatment of European Americans during World War II, but it did not pass the House of Representatives. Activists and historians have identified certain injustices against these groups. I suppose that some injustices were done, but those were times of war and strong measures were needed.

Leave a Reply